Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,772

- Reaction score

- 15,808

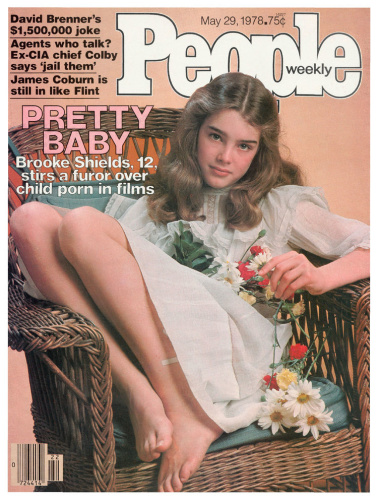

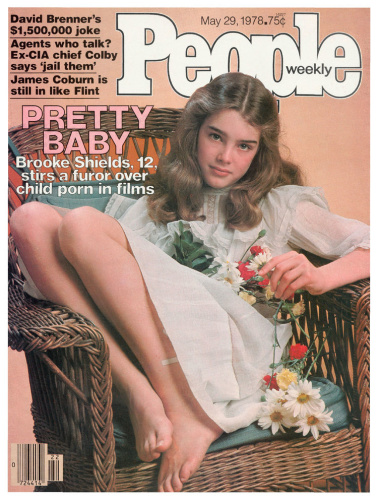

People May 29, 1978

Photographer: Harry Benson

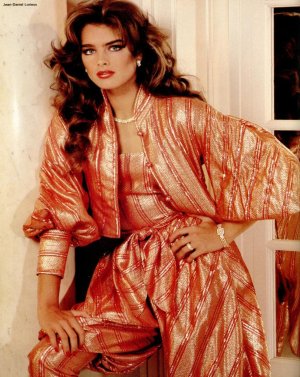

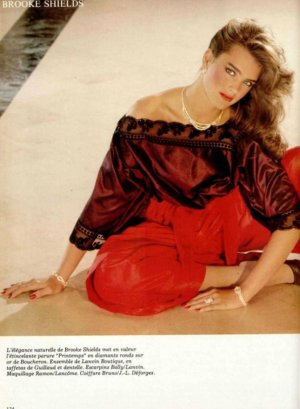

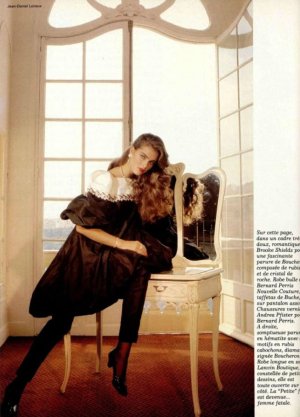

Featuring: Brooke Shields

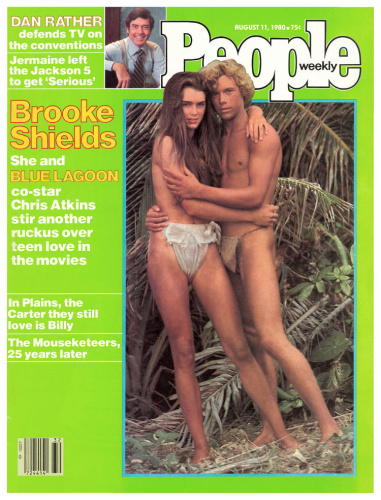

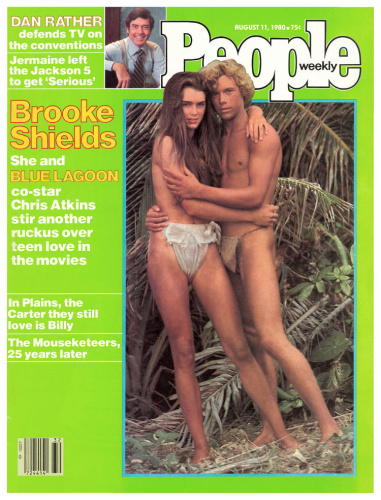

People August 11, 1980

Featuring: Brooke Shields, Chris Atkins

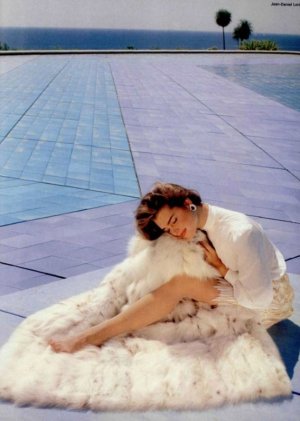

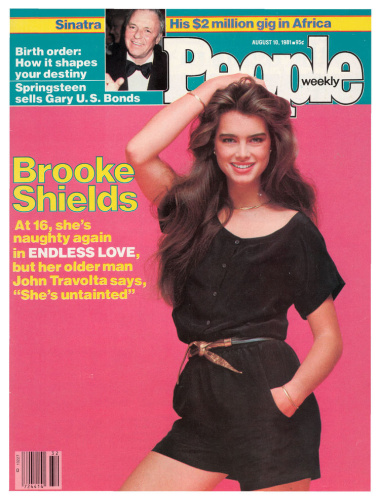

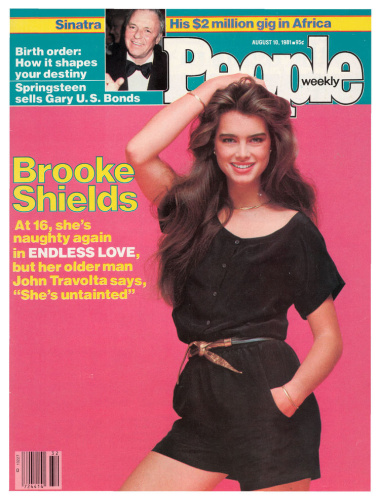

People August 10, 1981

Photographer: Mary Ellen Mark

Featuring: Brooke Shields

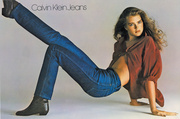

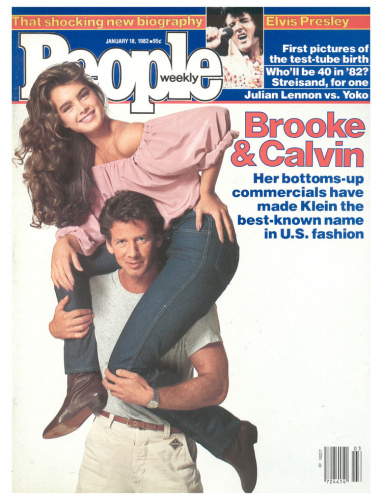

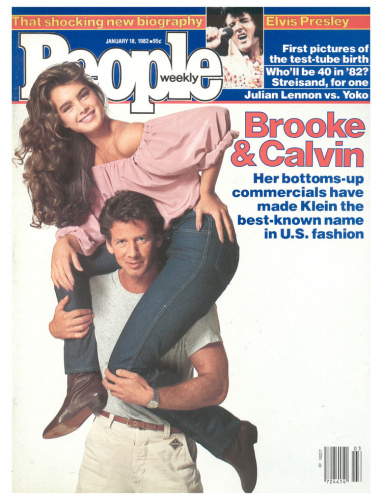

People January 11, 1982

Photographer: Richard Avedon

Featuring: Brooke Shields, Calvin Klein

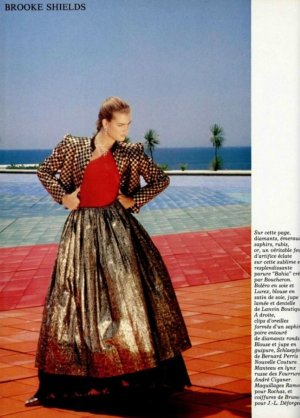

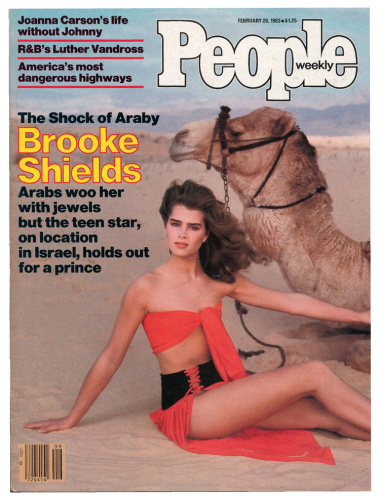

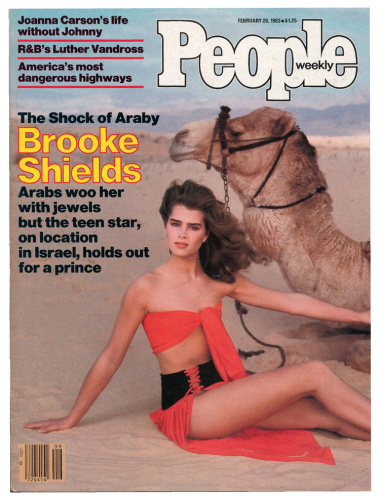

People February 28, 1983

Photographer: Douglas Kirkland

Featuring: Brooke Shields

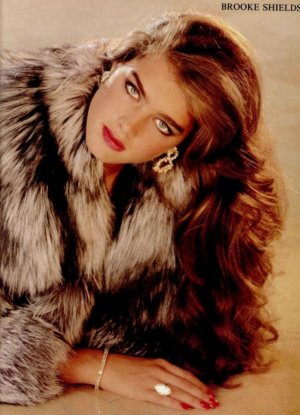

People

Photographer: Harry Benson

Featuring: Brooke Shields

People August 11, 1980

Featuring: Brooke Shields, Chris Atkins

People August 10, 1981

Photographer: Mary Ellen Mark

Featuring: Brooke Shields

People January 11, 1982

Photographer: Richard Avedon

Featuring: Brooke Shields, Calvin Klein

People February 28, 1983

Photographer: Douglas Kirkland

Featuring: Brooke Shields

People