Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,582

- Reaction score

- 20,793

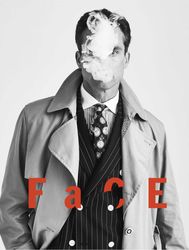

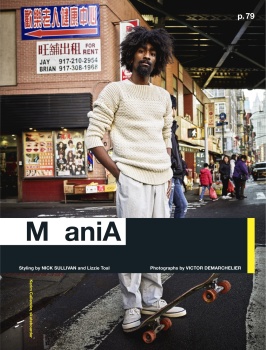

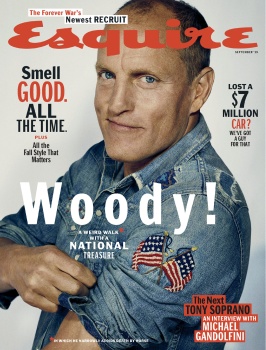

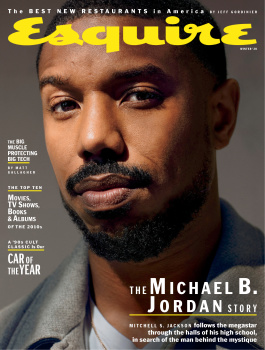

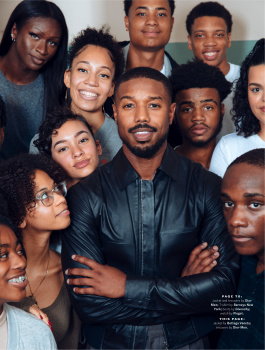

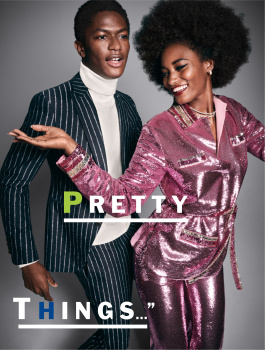

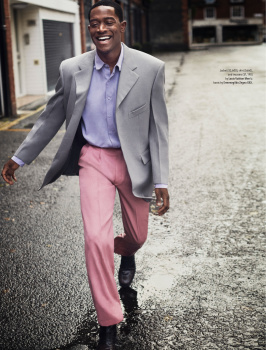

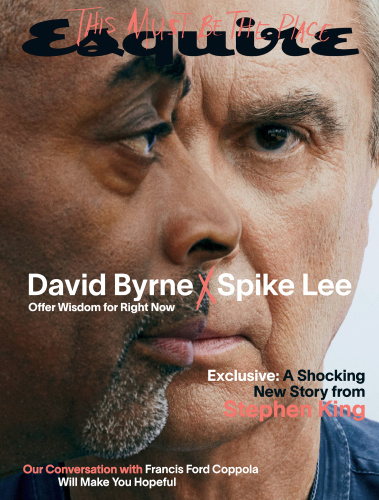

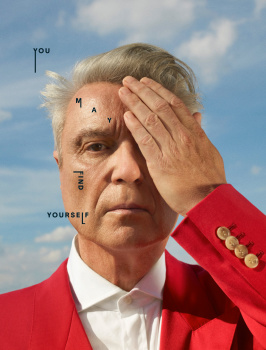

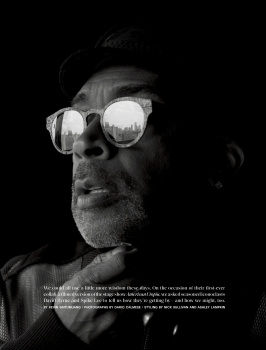

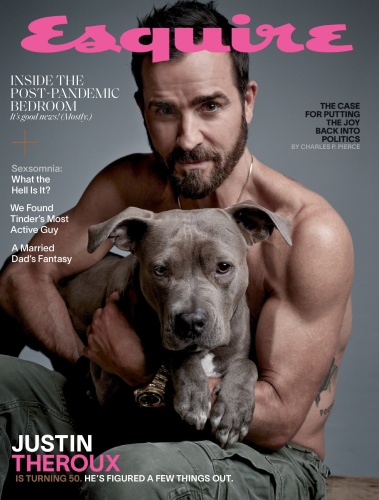

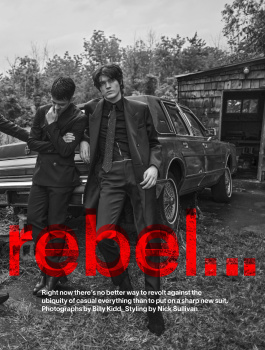

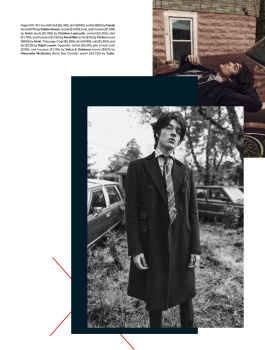

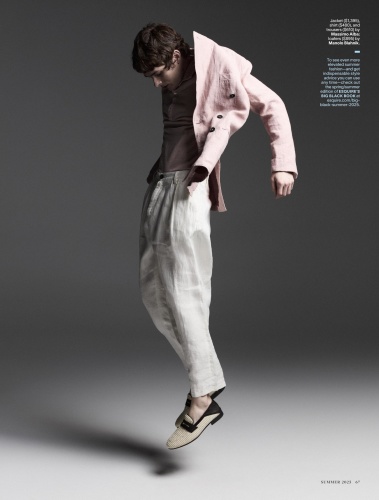

How I Became… Fashion Director at Esquire

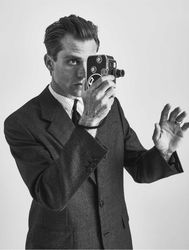

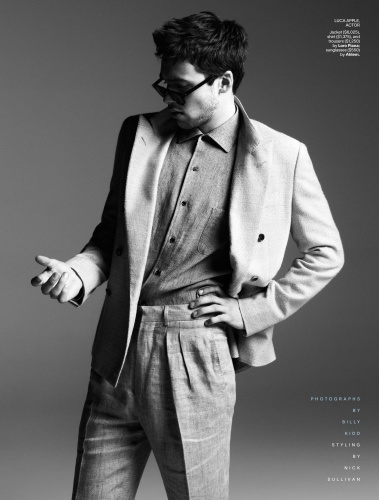

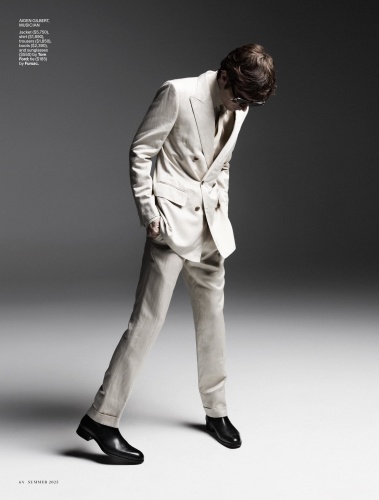

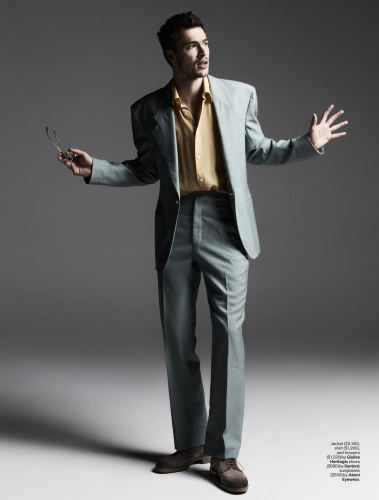

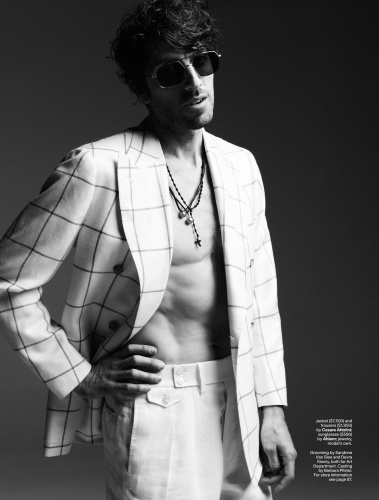

After talking his way into Italian tradeshows for his first editorial job, Nick Sullivan has worked at some of the biggest men’s fashion titles and held the rof fashion director at Esquire US for 14 years. Here, he shares his career advice.

NEW YORK, United States — Nick Sullivan’s path to a career in fashion began with his undergraduate degree in French at The University of Warwick. The British-born fashion director developed a passion for languages and culture, which led to his first writing job at a multilingual trade magazine. From there, Sullivan went on to work at the UK edition of Esquire before he was hired at Arena magazine and later at British GQ. In 2004, he made the move to New York with his wife, daughter and eight-week-old son to take on the role of fashion director at Esquire in the US, where he continues to work today. Despite the declining circulation rates of print publications worldwide, Esquire US has experienced a rare circulation increase of just under 3.5 percent between 2016 and 2017.

How did you land your first job in fashion editorial?

I tried a number of different avenues for work and one was as an editorial assistant for a magazine called International Textiles, which was a business-to-business publication printed in English, French and German, analysing trends on the runway along with trends in yarns and cloth. I studied French at university, and at that point, I was learning Italian as well. Within three months, I started going on trips to Italian tradeshows for textiles, about which I knew absolutely nothing. But anyone else that I ran into, budding fashion journalists who are now big editors — none of them studied fashion. They studied classics or psychology or literature or history. If training is too vocational, you get boxed into something, and if you’re expressing cultural opinions, you need to have a reference point outside that industry.

I was lucky that I had to learn something quite technical in terms of cloth, but I hadn’t trained for it. I started as an inexperienced writer, who became an inexperienced stylist, and then became an inexperienced still life stylist. I was learning all the time. I still am today. I’m not just regurgitating all the stuff I’ve already learnt, I’m still learning all the time.

What lessons did you learn at the start of your career?

Don’t dream of a big job and think you’ll go sailing straight to it, because it’s not going to happen. Things are more fluid now, especially in the media. Go anywhere you can get experience. It might tell you that you don’t even like that industry, but it will certainly stand you in good stead. It is stepping stones. As you change jobs, you accrue experience, and then more people know who you are. It is like growing a plant — eventually, it will grow if you persevere. I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time and to recognise that I had found something that I liked doing. Once you have found something that you like, you make progress.

I did a long stint with Dylan [Jones, editor of GQ UK], which was probably the best experience and most formative part of my life. I’d crossed from Esquire, which was in its infancy, to Arena, which was very cool — and I wasn’t very cool, so it was a bit like being in the deep-end. But I wrote a lot and I started shooting more. Working on those magazines was the best experience, because we had no budget and not enough people — we just got on with it.

What skills have been fundamental to your career success?

Languages are really helpful. If you’re talking to a designer or some delicate creative type, who doesn’t speak a lot of English and is trying to express something that is quite intelligent, they are not going to sound as intelligent if they only have seven words of English. But it’s not just about the language — if somebody thinks that you understand the culture of what they mean, you have an advantage. There are ways to talk in English to someone about the culture of fashion or, say, an Italian’s culture around food, art, the history of the architecture. The broader your cultural interests are, the more useful it is. You need a big, broad filter to be able to talk specifics.

How has the role of fashion director changed since you began?

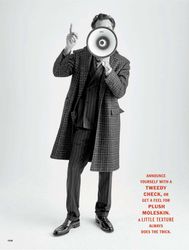

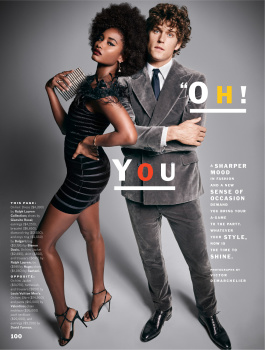

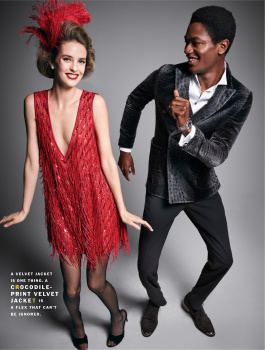

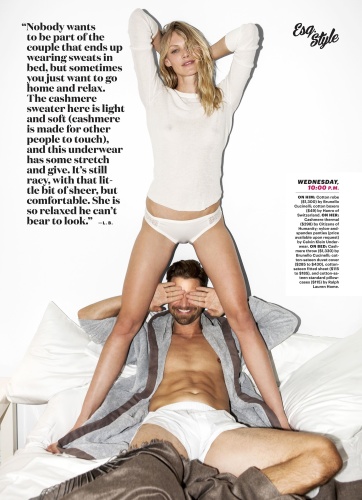

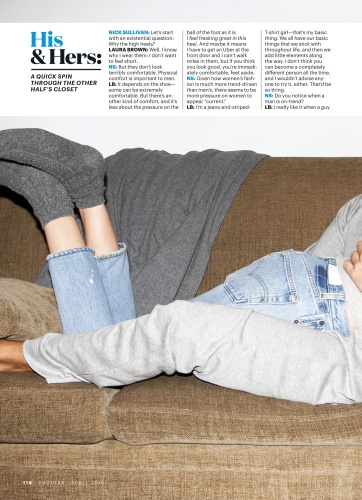

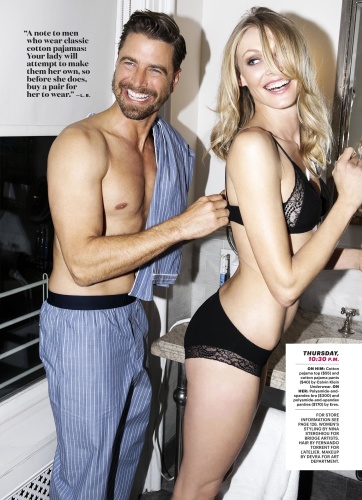

A fashion director now has a multiplicity of jobs. One week, I’ll go to Switzerland for the watch fairs, and then I’ll go to Milan to the fashion shows, or to interview someone, or to go to a factory. I would hate to have one job. If I was just styling or just art directing, just writing about watches or just writing fashion coverage, I would probably be bored. In men’s, less so in women’s, you can be a jack of all trades and that gives it variety.

Because we had no budget and not enough people, we just got on with it. When I started out, a fashion director had a very simple meaning — you did photoshoots and you oversaw the editorial plans, who you shot in terms of celebrities and how you’d approach it. Now, there are so many platforms in which you have to represent your title — your brand — online, on social media, in collaborations, in panels and interviews. You don’t represent yourself, you represent a brand. In my case, it’s Esquire.

What advice do you have for someone starting a career in fashion editorial?

It is not beneath you to put clothes in bags. I’ve had people interning who say, “Oh, you want me to put that in that bag?” as if some lower life form has to do it. When I’m on shoots, I’m filling trunks and crawling into the backs of trucks because that’s part of the job — you can’t cherry pick the bits that you like. It is not having lunch with a designer in Barneys and then going home in your limo. A lot of this stuff is a team effort, especially because there’s never enough budget, so you have to muck in in some way.

I don’t care where I read someone’s writing, but if I read it or I hear them doing a blog, a podcast, or I see a shoot, that’s real. The appearance of success has sort of taken over from actual success, but all the social media in the world is not going to protect you. You’ve got to pay your dues, to work on your reputation, and actually do something to earn a reputation. Having likes is not a reputation. It’s not going to make up for a lack of talent.

Is there anything specific a junior seeking an editorial job should do?

I always say, “Go to a factory,” to understand how they make things and why they make things that way. It also helps you to realise when you’re having the wool pulled over your eyes about the luxury of things. With watches, for example, you can understand why it takes five years to develop a new watch case and why there are so many noughts on the end of them. Having that understanding of not only the nuts and bolts of making things, but also the passion of the people who believe in their brands — you don’t get it until you see the people making it.

You’ve got to know more than other people, and if that means you gravitate towards one subject that you can control, that’s great. The more you do it, the more you will know, and the more you know, the more advantage you have. That knowledge has to come from lots of different people, not just what you learn on Instagram from looking at pictures. If you have a passion for something, you’ll find the opportunities.

What attributes do you look for when hiring someone?

Too many people try to talk their way into a job, but I think you have to look and listen your way into a job. You’ve got to drink up as much as you can, even more now, since there are so many platforms to do it on. Don’t spend all your energy telling people how fabulous you are — find out why they’re fabulous, or what’s interesting about them. Listen to them, especially if you’re a journalist, but also if you’re a stylist. You have to get your ideas, your ingredients, from somewhere and make your own thing from it.

Business of Fashion