The 60s were swinging alright! In a scorching memoir Mary Quant tells how she fostered a spirit of revolution in a decade that changed Britain forever

By Mary Quant

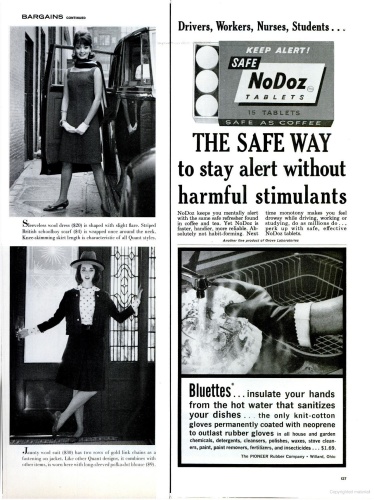

When I opened my first shop, City gents were still carrying tightly furled umbrellas and wearing bowler hats. It was into this world that I launched my new ideas about fashion. Reaction was swift. Strolling past the shop window, one of these respectable gents came to an abrupt halt. Appalled by what he saw, he lifted his umbrella and beat it furiously against the glass.

Soon this became a regular occurrence: the window would shake and there’d be accompanying shouts of ‘immoral!’ and ‘disgusting!’ as yet another bowler-hatted gent registered his outrage.

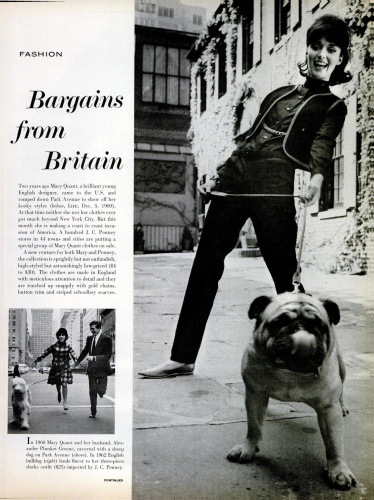

What had I done? Not much, by today’s standards. On a backing of hardboard, I’d pinned some cheerful mini-skirts over a few pairs of tights. Then I compounded my sin by installing some leggy white mannequins I’d had specially designed. Such was the fury of the City gents that they seemed to lose the ability to speak — instead, they reverted to beating the window in silence. The year was 1955. I’d just opened the shop, Bazaar — and an accompanying restaurant in the basement — on the King’s Road in London with my husband Alexander Plunket Greene.

Let me give you an idea of Fifties Britain. The war had ended ten years before, and most people had returned to their gardens and allotments hoping life would revert to how it was before the hostilities. Rationing had grown steadily worse: no eggs, no meat, no sweets, limited transport — yet the attitude was: ‘Don’t rock the boat.’ Government control had become a habit: if you went to an off-licence, you were told how many cigarettes or what alcohol you could buy.

If you went out to tea, you took your own private plate of rancid butter. If you had a bath, there was a rota and you were allowed only five inches of water. Women wore Lisle stockings and suspenders. There was no central heating and no hot water except from geysers that had a habit of exploding. Meanwhile, fog permeated everything. Fog was a smell. Fog was a colour. Fog started in October with children collecting money for Guy Fawkes and did not end till March.

Young people like me had nowhere to go to keep warm except the cinema. We were bored and frustrated. Uninterested in science and politics — which, in our view, merely led to war — we poured in our thousands into art schools. That’s why art schools became the hotbed of new ideas. Thus, out of a ten-year gloom burst one great electric charge of energy, high spirits and originality.

The new ethos was: ‘If you want it, do it yourself.’ And what we wanted was art, theatre, film, design, fashion, food, sex and, most of all, music and dance. So where did I fit into all this? As the daughter of two teachers with first-class degrees, I’d always seen myself as a duffer by comparison. What obsessed me from a young age was fashion.

When asked in a school exam which side I’d take in the battle between the Roundheads and Cavaliers, I compared their underwear, dress fabrics, colours, accessories, hairstyles, hats, make-up, toiletries and demeanour. Naturally, I came down strongly on the side of the chic Cavaliers. This so stunned the schoolmaster that he gave me the highest marks ever awarded.

I’d been cutting up bedspreads and trying to make my own clothes since the age of six or seven. My inspiration was a little girl I’d once glimpsed in a tap-dancing class: a vision of chic in a black skinny-rib sweater, seven inches of black pleated skirt and black tights under white ankle socks and black patent leather tap-dancing shoes.

After that, all I wanted to do was design clothes and tap-dance. My parents, however, were dead against me going to fashion school. There’s no future in fashion, they said — and from their perspective, they were probably right.

In the first half of the 20th century, fashion was simply not a very English thing to do. New things were not much admired — they were seen as déclassé, like having to buy your own furniture. Even grand young women had their frocks made by aged retainers living in the upstairs attics. The young women would point out the charms of some delicious dress in French Vogue — and Mabel, the ex-nanny, would have a bash at making it, with some heavy fabric bought in the sale at Mayfair department store Jacqmar’s.

My parents and I settled on art school as a compromise. So I enrolled at Goldsmith’s, where I met Alexander Plunket Greene, known as APG. My future husband was incredibly handsome, not to mention exotic, a quality he shared with his whole family. His father Richard, an inveterate womaniser, was a musician and close friend of the novelist Evelyn Waugh; his mother Elizabeth — related to philosopher Bertrand Russell — had taken up motor-racing. His great-grandfather Hubert Parry wrote the music to Jerusalem.

I first encountered Alexander at the art school’s fancy dress ball in 1953 when I was on a float wearing just black mesh tights and strategically placed balloons. APG said it was lust at first sight; I was bowled over. ‘Come to Paris,’ he said. ‘I’m busking outside the George V Hotel.’ So I did.

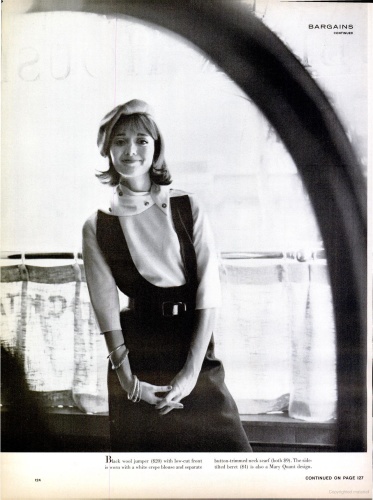

Though I fell madly in love with France, I wasn’t interested in Paris couture. I wanted to design solely for myself and other students — most of whom dressed like models for the painter Augustus John, with dowdy skirts and a deliberately ill-kempt look. My own look at art school consisted of a wide elastic belt at the waist, shorts or peg-top skirts, tight neat sweaters, knee socks or theatrical fishnet tights, and a triangular polka-dot scarf tied cowboy-style.

When Alexander and I finished art school, I worked as an apprentice in a very smart hat shop and took lessons in pattern-cutting in the evenings. APG was working in Selfridges selling ginghams and strips of elastic by the yard. So we had jobs, but no money.

But everything changed in 1953 when he turned 21 and inherited £5,000. He decided to start a business with me and a friend of ours, Archie McNair, who’d launched the first espresso coffee bar in Chelsea. The King’s Road back then was a rather shabby and charming artists’ village. Locals went out in dressing gowns and slippers in the morning to buy bread from Mrs Beaton the baker’s. It was against this backdrop that we started Bazaar, as well as Alexander’s restaurant in the basement.

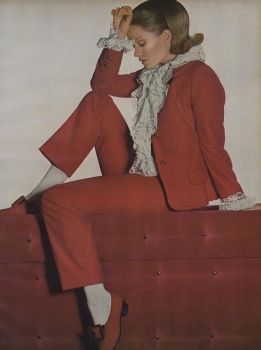

Buying material on our limited budget was a big problem — until I borrowed a Harrods credit card from Alexander’s mother. The advantage was that nobody got cross with you for at least a year about not paying it off. Next, I chopped up Butterick patterns to achieve roughly the right sizing — always size eight, because wartime rationing meant everyone was lean. I deliberately used overtly masculine suiting fabrics and mixed them with fragile feminine textures, like chiffon, satin crepe and georgette. There were hipster pants and skirts, tunics and knickerbockers. The dresses, with cowl-like or Peter Pan necklines, were an easy fit to the top of the hip bone and then fell in flairs or pleats. And best of all, the dresses were short, short, short.

I think the Sixties mini was the most self-indulgent, optimistic fashion ever devised: young, liberated and exuberant — and the beginning of women’s lib. I was the first to design them here, while fashion designer André Courrèges was shortening hemlines in France.

From the very start, customers were four-deep outside the window. Within ten days, we had hardly a piece of the original merchandise left. Some mornings, customers would grab dresses from me as I walked to the shop. Another great hit was the tights. They didn’t exist outside the theatre, so I persuaded theatrical manufacturers to make some up for me. But my all-time hottest seller was a white, rounded Peter Pan collar, made in plastic with a press-stud centre, that you wore over a plain jumper.

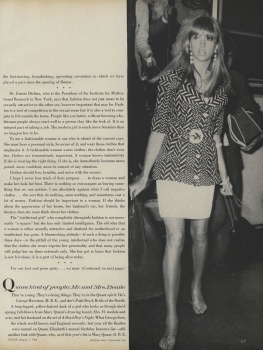

And so the King’s Road became a catwalk for the new mini-skirt, with American press photographers there to try to capture Swinging London. Life became a running party. Among those who spilled into the shop were actresses Claire Bloom, Susannah York, Audrey Hepburn, Brigitte Bardot, Leslie Caron and, later, photographers David Bailey and Richard Avedon, film directors Stanley Kubrick and Joe Losey, and models including Jean Shrimpton and Twiggy.

I got to know John Lennon in the early Sixties after he bought his black leather cap and other items from the shop. We became affectionate friends until the foreign press gossiped of an affair — which, I’m sad to say, was not true. But he did send me messages of huge encouragement later when I had a difficult pregnancy. John was a very sweet but often depressed man. I sat next to him at a lunch at Foyle’s to launch his book of rhymes and doodles, In His Own Write. He was paralysed with fright at having to stand up to speak. When it became clear he wasn’t going to, a horrid bully of a man stood up and said how disgracefully rude and insulting it was of Lennon not to deliver a speech. I clutched John’s shaking hand. He was close to tears.

As well as John, the other Beatles frequented the shop, too, and so did the Rolling Stones. George Harrison’s wife Pattie Boyd and her sister modelled my designs. Our staff were, for the large part, very, very young and mostly debutantes. In fact, we were overrun with rich debs, who seemed to run Chelsea in those days. Another early recruit was a boy of 16 or 17 who came into my office, dressed in an Edwardian suit and carrying a silver-topped walking stick. He was followed by his mother, who begged me to take him on as she couldn’t deal with him and he wouldn’t go to school. I agreed to let him fetch and carry. He stayed less than a year. Six months later, Andrew Loog Oldham was managing the Rolling Stones.

Meanwhile, Alexander’s restaurant had become the most fashionable in Chelsea, with a chic clientele. Unlike many restaurants, we never rang the Press after someone famous had dined with us, so most of them came back again and again. I remember Grace Kelly and Prince Rainier being there with two friends on table number one. They were flirting monstrously. Two minders, their silhouettes swollen with hidden guns, sat at separate tables, eating the most expensive things on the menu.

Once, I was invited to join Brigitte Bardot and her second husband, the French actor Jacques Charrier. Bardot was preening herself deliciously as the entire staff — the Italian waiters, chefs and commis — fell into disarray with excitement. Playing up to all this, she had no idea they were actually fans of Charrier.

Our speedy success left us as stunned as everyone else. We couldn’t quite believe it, or cope. Our banking, for instance, was done only when the till drawer would no longer shut. Yet after taxes and other costs, there was often very little left. So although Bazaar had become a friendly meeting place for actors, musicians, photographers, models and film directors — an outrageous day-and-night party — we were worrying ourselves to death about whether we could keep afloat.

When Alexander and I married, two years after the opening, we couldn’t afford to furnish our flat. So we painted it white, bought deck-chairs, installed his vast wooden gramophone and slept on a bed that was a present from his mother. Despite our lack of furniture, we didn’t hesitate to ask Elizabeth David, the great cookery writer, to dinner when she complained no one ever dared invite her. We hired a trestle table and chairs from Liberty, borrowed cutlery, plates, glasses and a frying pan from our restaurant, and cooked sausage and mash. The next day, House & Garden magazine came round to photograph the flat — then Liberty took everything away.

Apart from our takings from the shop and restaurant, we relied on our winnings from gambling. Even our cat, Poisson, had been won as a kitten from a man called Fisher during a game of spoof. With top-rate income tax running at more than 90 per cent, gambling was a part of life in London. So, since it was illegal to gamble regularly at the same address without a licence, we started a floating craps game in our Mary Quant delivery van.

This proved to be a very popular and democratic venue, as well as totally legal. Toffs, pop singers, restaurateurs, rag-trade veterans, professional gamblers and rich society beauties all came to our van. Most evenings, we’d dine at Alexander’s, then move on to the Esmeralda’s Barn nightclub in Knightsbridge — owned by the notorious Kray brothers — to dance till midnight, and finally start to gamble.

One night, though, Alexander and I had a major row about the gambling and I went to bed. He went out as usual, in his ankle-length racoon fur coat, which he had bought second-hand from Moss Bros, and won an enormous sum of cash. On his way home, he stopped off at a flower shop and bought their entire stock. I awoke to find buckets and buckets of flowers and twigs through the living-room and bedroom and on the stairs, with Poisson swinging from branch to branch.

Gambling also took us most weekends to Le Touquet in France. Depending on our finances, we stayed at the Mercure Grand Hotel or we took a small room above a greengrocer’s shop, where the only furniture was a bed and a tin bidet.

It was always such fun to be with Alexander. The trouble is, he was also a hell of a womaniser — and that makes life bumpy. Women would phone me and say: ‘Can Alexander come out to play today?’ And I’d find little presents for him left in the car. But I was working so hard, and was so obsessed with design, that I knew it was partly my fault.

Adapted from Mary Quant: My Autobiography, to be published by Headline on February 16 at £25.

© 2012 Mary Quant.

Those are amazing!

Those are amazing!

i meant for the crayons....

i meant for the crayons....