simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,241

- Reaction score

- 1,026

Live Streaming... The F/W 2025.26 Fashion Shows

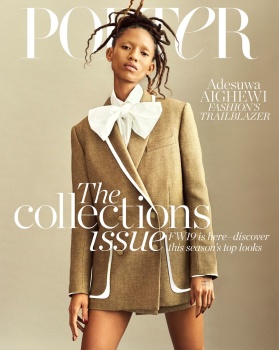

net-a-porterA teenage prodigy who won an internship at Nasa, ADESUWA AIGHEWI is a powerful voice for social change. The model and filmmaker talks to SARAH BAILEY about her passion for promoting the craft skills of African artisans and her close bond with Karl Lagerfeld, but says it’s her late brother who is the real wind beneath her wings.

Adesuwa Aighewi greets me on the steps of her London modeling agency, a mug of tea in hand. She’s dressed in a transparent tank and lingerie slip, square-toed Balenciaga logo pumps, with a pink shearling coat wrapped around her like a dressing robe (her state of punkish déshabillé is, she explains, a consequence of impromptu all-night dancing). “I had a day off,” she laughs. “I was like, ‘No one is going to touch me today. I’m just going to eat and dance.’”

Though she mostly dwells in Harlem these days, Aighewi has a London crew (mostly fashion folk) who can be called on when she wants to get lost in music. “It’s really hard to have friends outside the industry because you can’t plan. They have to be able to move like water, like you.”

The protean analogy is fitting for the model and filmmaker, whose career is steadily rising – and not only from a slew of high-profile campaigns and runway appearances for FW19 and SS20 that have seen her lend her simultaneously fierce/delicate beauty to houses from Fendi and Chanel to Dior Haute Couture. But last year saw the release of her directorial debut, a short film titled Spring in Harlem, about a posse of sassy Muslim girls talking about their relationship with the hijab. “I wanted you just to hear them and find them relatable, like ‘Yo, this is a girl with a piece of cloth on her head. That’s literally it. You don’t need to be scared.’” (Incidentally, Aighewi, who is of Nigerian/Thai/Chinese descent, is a Buddhist like her mother.) She’s also currently busy researching a docu-series of stories from Africa, having spent the summer traveling around the continent, “just learning and observing all nations, literally hanging out, like, ‘You sell mangoes? Yo, what’s your deal? Let’s hang…’”

Crashing back into the seasonal fashion whirlwind has been intense. “I literally landed from Nigeria and the next day I shot the cover of Vogue Thailand. It was the first thing that I ever got when I cried. I didn’t realize until the day before that I was the second black person – ever – on the cover. When I was shooting, all I could think of was my mom saying, ‘Why didn’t you smile more?’,” she laughs. Since then she’s shot campaigns in New York, London and back again in quick succession, though she looks remarkably fresh considering. “Ha, I slept in an oxygen chamber! I was exhausted. I texted my IV people and they have an oxygen tank and they just pump you in with pure oxygen and it helps you recover. Apparently, [basketball player] LeBron James did it every day for a bunch of hours. It’s amazing. That’s why I look happy!”

Born in Minnesota to academic parents (her Chinese/Thai mother and Nigerian father were both environmental scientists), Aighewi grew up mostly in Nigeria until she was 13. She paints an idyllic picture of a bookish, tomboyish childhood in which fashion and the glossy world of appearances were an anathema. “I don’t think my mom has ever said, ‘You look pretty’; she was always, ‘What grade did you get?’” Days were spent climbing trees, nights reading by lantern light; but this period was interrupted by a terrible tragedy when Aighewi’s elder brother, Esewi, died when she was 13. The pair were so close, they had been like twins (“people thought we were twins”). They had both wanted to be doctors but, after his death, “I had zero interest in medicine, because we were like, ‘We’re gonna save the world together’ and we used to compete and everything, and then all my drive was gone.”

After Esewi’s death, the family left Nigeria for the States. The move sounds traumatic. Aighewi remembers the distressing moments of alienation, like being asked if her little brother (only four years her junior) was her son when they were taking a train together; her highly qualified parents struggled to find employment: “My dad has a really thick accent and my mom does as well. They are both Ivy League educated and they couldn’t even get jobs. Can you imagine?”

Precociously intelligent, Aighewi continued to study, enrolling in the University of Maryland Eastern Shore to read chemistry at 15. She even earned a coveted internship at Nasa. “I was in charge of our group and our topic was global warming and ways to slow it down. My professor was researching phytoplankton and how it can be used to reduce the amount of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere.” But when she talks about this period, it’s clear her heart was broken and, when she was scouted by a modeling agency in her junior year, she quit school to spend a year in New York and try her hand. “And my mom would call me every day, saying ‘You didn’t finish school, that’s not honorable’,” she groans. (For the record, she did return, cramming like a demon so she could graduate at the same time as her friends.)

Her early experiences of modeling sound like a mixed bag, marred generally by lackluster casting opportunities, occasionally outright sleaze. She remembers traveling from school in Maryland twice to meet with Victoria’s Secret and an agent telling her: “‘They are waiting for your breasts; you need to have something’, and I was like, ‘Bro, my mom doesn’t have t*ts, no one has t*ts on my mom or my dad’s side.’” Does she think she was expected to get implants? “A lot of creepy things happen in fashion and, yeah, I figured if I tattooed my chest, it would just end the conversation entirely.” And that is exactly what she did.

It was only later that she had the epiphany that fashion could be a powerful platform. “I remember specifically being in Harlem and being like, ‘F***, modeling can actually be useful for something.’” And while a new openness from the industry to casting girls with diverse skin-tones, locs and tattoos has allowed Aighewi to rise, her own contribution to challenging and shifting those beauty norms cannot be underestimated. Aighewi brings up Alek Wek and the pioneering role she has played for black models. “When I see her, I just want to hold her,” she says, her voice cracking with emotion. “People think that as a model there are people behind you pushing, but you’re in the front, you get all the hits.”

Her early experiences of modeling sound like a mixed bag, marred generally by lackluster casting opportunities, occasionally outright sleaze. She remembers traveling from school in Maryland twice to meet with Victoria’s Secret and an agent telling her: “‘They are waiting for your breasts; you need to have something’, and I was like, ‘Bro, my mom doesn’t have t*ts, no one has t*ts on my mom or my dad’s side.’” Does she think she was expected to get implants? “A lot of creepy things happen in fashion and, yeah, I figured if I tattooed my chest, it would just end the conversation entirely.” And that is exactly what she did.

It was only later that she had the epiphany that fashion could be a powerful platform. “I remember specifically being in Harlem and being like, ‘F***, modeling can actually be useful for something.’” And while a new openness from the industry to casting girls with diverse skin-tones, locs and tattoos has allowed Aighewi to rise, her own contribution to challenging and shifting those beauty norms cannot be underestimated. Aighewi brings up Alek Wek and the pioneering role she has played for black models. “When I see her, I just want to hold her,” she says, her voice cracking with emotion. “People think that as a model there are people behind you pushing, but you’re in the front, you get all the hits.”

One of Aighewi’s most powerful champions was Karl Lagerfeld, who embraced her at both Fendi and Chanel. “You know what’s crazy – I knew Karl would get me. And he was so dope.” She treasures fond memories of spending time in his library, “literally smoking in my robe and reading all those books, thinking, ‘This man’s brain is crazy.’” She was planning to film him shortly before he died. “I just wanted to ask him questions that people don’t usually ask him, like, ‘Are you happy? Why do you like cats?’ And he was down [for it]. He said his godson wanted to be a director and he was going to come too, and I was like, ‘Awesome’. But then he passed the next week and it was really sad. He was super, super cool. I wish I’d had more time with him.”

Like Lagerfeld himself, Aighewi is a restless polymath. Alongside her modeling and filmmaking, she’s putting the finishing touches to a book inspired by her late brother, drawn with a Nigerian anime artist from Texas who she met through Instagram. More ambitious still is a cross-cultural initiative bringing together the craft skills of African artisans with fashion designers based in the West to create the kind of products that hype beasts and tastemakers would be proud to buy and wear. Called Legacy Project, its official unveiling will come later this year, but she cannot resist showing me images on her phone of Benin bronze casts about to be turned into belt buckles; coral beads traditionally worn by African chiefs recast in cool metals. “I want to create change on a big scale,” she grins. The idea is that profits will go back to the African makers and that other creators will follow suit and collaborate and use the platform, too. “All the money that’s made is in a circle, going back in,” says Aighewi. “All I want to be is a catalyst, just sparking the fire.”

She’s not unaware of the irony that has led her to find this path. “If my brother never passed, I wouldn’t be in this job… When something like that happens, it changes your reality; it changes the way you see everything; so you can either succumb to it and wallow in the misery or find the silver lining,” she half-shrugs, half-smiles at the poignancy. “Actually, I was thinking recently, I wonder what he would think of what I was doing. But he was fire. He was badass. I think he’d really like it.”