You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Anjelica Huston

- Thread starter Kellz

- Start date

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 48,027

- Reaction score

- 8,807

jexxica

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 14, 2009

- Messages

- 31,710

- Reaction score

- 371

For Sofia Coppola and Anjelica Huston, Oscar’s a Family Friend

No matter who takes home Academy Awards this weekend, Sofia Coppola and Anjelica Huston will remain an exclusive club of two: the only third-generation winners in Oscar history.

Ms. Coppola, 43, the writer and director of films such as “The Virgin Suicides,” “Somewhere” and “The Bling Ring,” won an Academy Award for best original screenplay for her 2003 film “Lost in Translation.” Her father, the filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola, has won five Academy Awards, three of them for “The Godfather, Part II.” And her grandfather, the composer Carmine Coppola, won for best score, for that film.

Ms. Huston, 63, an actress and writer, won the best supporting actress prize for her breakthrough role as Maerose Prizzi in 1985’s “Prizzi’s Honor,” directed by her father, John Huston, who was also a screenwriter and actor. He received 15 Academy Award nominations and won twice. Ms. Huston went on to star in “The Grifters,” “Crimes and Misdemeanors” and “The Addams Family.” Her grandfather Walter Huston won the Oscar for best supporting actor for “The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” in 1948, directed by his son. The second volume of Ms. Huston’s memoir, “Watch Me,” was published last year.

In a suite at the Trump International Hotel, over kale salads and Dover sole, as well as a Bloody Mary for Ms. Huston and water for Ms. Coppola (“I have a parent-teacher conference later”), the pair spoke about their showbiz clans and infamous acting debuts (directed by their fathers), the routes they took to their own success and their shared debt to fashion.

PHILIP GALANES: Family dynasties are so appealing: one generation nourishing the next. Do they?

ANJELICA HUSTON: Our fathers took great big bites out of life. And we watched them taking pleasure in the senses, celebrating characters. Mine would have been as happy in a prison as a palace — as long as there were interesting people around.

SOFIA COPPOLA: So many interesting people coming through. And my dad liked us kids around. I’d be at dinner, sitting next to Vittorio Storaro, the great cinematographer, talking about color and light.

AH: And now I take big bites.

SC: You can’t grow up like that and not have an appetite for living.

PG: I heard a tape of Sofia’s dad interviewing her as a little girl. “What do you want to be when you grow up?” he asks. And you say: “Middle sized — not too fat and not too skinny.” Was there a family expectation about your careers?

SC: No, but my dad always talked to us about writing. I remember being 12, and his saying: “Now, in the second act .” But it didn’t feel like expectation, more like exposing us to something that was important to him.

AH: We had this dress-up hamper, and we were always putting on costumes. I remember once, at 3 or 4, putting talcum powder on my bare bottom and saying: “I’m Japanese.” There were roars of laughter, and I thought: “This is it!” But my father would have preferred I be a financier because my family was notoriously bad with money.

SC: We were up and down, too.

AH: It’s the artistic situation. But my dad knew I was bound to be an actress. I used to imitate all his girlfriends. He liked it, despite himself.

PG: He must have. He gave you your debut in his film “A Walk With Love and Death.”

AH: Well, that’s what you get for saying: “I want to be an actress, I want to be an actress.” Suddenly, this role came up in one of his movies. But at the same time, Franco Zeffirelli had put a school call out to find Juliet for his “Romeo and Juliet.” They came to my school. And they liked me and asked me to come back to meet Zeffirelli. But my father sent him a letter saying, “My daughter will be working with me.” I was not happy about that.

SC: It sounds a little possessive?

AH: I wanted to be in Italy with Zeffirelli. As you can tell from my opus, I have more feeling for the bad girls. I like a bit of picante. And the part in my father’s film was so boring. He didn’t even let me wear makeup because 15th-century maidens didn’t. And I was obsessed with makeup. No, my father and I didn’t get along on that movie.

PG: Tell us about your debut in “The Godfather Part III.”

SC: I didn’t have any acting aspirations. I just didn’t want to go back to college after Christmas. So, when Winona Ryder fell out, I read her part during a table read. Someone said, “Sofia can do it.” I probably looked more like a real Italian girl than these movie stars. I said O.K. I was at the age when you want to try everything. I had no idea there would be so many opinions about it. But it was awkward. When you’re 18, you don’t want your dad telling you what to do. I had to kiss Andy Garcia in front of him.

AH: I had to kiss Assi Dayan in front of mine. And there he was, looming over me and angry looking. I said: “This isn’t exactly conducive.”

PG: The reception to those films wasn’t exactly stellar. People said

AH: It’s our fault.

SC: Yeah, yeah. Because we’re not good actresses.

PG: How did you process that? Did you get angry with your fathers?

SC: I remember going back to art school, and I see this issue of Entertainment Weekly. It’s me on the cover, and the headline says: “Did she ruin her father’s movie?” It was humiliating.

AH: People were hideous to her. And I thought she was beautiful in the film.

PG: I’m thinking of that scene in “Somewhere,” where Stephen Dorff buys his daughter every flavor of gelato in the restaurant.

SC: That’s very my dad.

PG: Is that what these roles were: gifts from loving fathers that backfired?

SC: No, I think my dad thought: “Sofia is more authentic, and she’s here.”

AH: Me, just the opposite. Mine thought he was launching my career and doing me a big favor.

SC: Did you not work with him again until “Prizzi’s Honor”?

AH: No, it took a long time recuperating from that experience.

SC: I never wanted to be an actress. And when I started thinking about directing, that experience of being in front of the camera was really helpful. It made me see how vulnerable actors are. Other good things came out of it, too. Steven Meisel asked to photograph me for Italian Vogue. And he introduced me to all these people in the fashion world, who embraced me, after everyone else was so harsh.

AH: I thought: I’d better put acting on ice for a while, because this isn’t going in the right direction. So, I came to America. My mother died very suddenly in a car crash, and I didn’t want to live in London anymore.

PG: How old were you?

AH: I was 17. She was 39.

PG: There’s a sad coincidence: Sofia lost her brother at about the same age.

SC: I was 15. I remember seeing Anjelica around then. She was a comfort to me. She was always like a fairy godmother. But it was a terrible shock, and had a big impact on who I am.

PG: We see that in your films: stories of people who are a little lost.

SC: For me, “The Virgin Suicides” was very much about losing my brother. The way the town loses these girls. But when you lose someone, the impression they made on you, our interactions with them, stay with you forever. They’re not completely lost.

AH: We can find them again.

SC: I connected to that teenage time because it’s supposed to be fun and carefree. But mine was exactly the opposite.

AH: I can remember coming downstairs the morning after I knew my mother had died, and it was like someone had sprayed everything matte. The shine was gone from everything.

PG: It’s like your staircase scene in “The Dead,” hearing the song your boyfriend sang to you before he died. The change that comes over your face is amazing acting.

AH: That was my father’s last movie. He was very sick. I was at the top of the stairs, and all I had to do was look down at my father in his wheelchair to have everything I needed to do that scene. It was all there.

PG: Amazing what we can make from loss.

AH: When my mother died, London was over for me. So, I put on my yellow Afghan coat and jumped on a plane to New York.

PG: On your own — at 17?

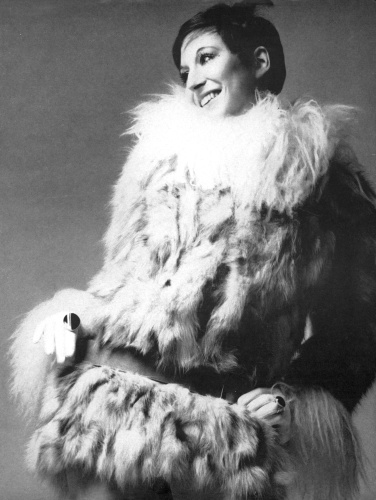

AH: My mother was a good friend of Dick Avedon. And my father was friends with Diana Vreeland. So between them, they asked me to do this trip to Ireland for Vogue. It was a beautiful layout, 30 pages. And when I got back, I did more work with Dick. And Harper’s Bazaar asked me to do some pictures. Before I knew it, I was modeling and being told, for the first time in my life, that I was beautiful. I loved it. I made my own money. I always hated having to ask for money.

SC: I love the pictures of Anjelica — did David Bailey take them? — where you’re wearing these ’40s dresses and bracelets. It’s my favorite look for a chic woman.

AH: Grace Coddington styled those pictures. She’s still the best stylist.

PG: So, how did you find Marc Jacobs, Sofia — or did he find you?

SC: When Marc did his first collection for Perry Ellis, it was the grunge collection. And when I saw it, I was excited. We were coming to New York, so I asked my mom if we could see it. I met Marc, and we just hit it off. We had a lot in common. A similar aesthetic, and we liked the same bands.

PG: Speaking of aesthetics, critics often say your films are “too aesthetic.” But you tell stories visually. Music plays a big role, and there’s not a lot of talking.

AH: My favorite kind of movie. I want to work for you.

SC: Sometimes, people think aesthetics are superficial. But I think they can be deep. I love the atmosphere and the visuals. So, I do what I love. Some people connect with it, and others don’t. It reminds me of something Anjelica told me in my 20s: “Not everyone is going to like you.” It saved me years of disappointment.

AH: It frees you up.

PG: What was the bridge back to acting, Anjelica?

AH: I had a boyfriend when I was modeling, Bob Richardson. He was a master photographer.

SC: I love his work.

AH: Always underappreciated. Also schizophrenic. Working with Bob was always about acting for the camera, feeling something. When we broke up, in the Los Angeles airport, I went to live with my father in L.A.

SC: Did you ever see Bob again?

AH: No, it was a big split. But it set me free. There was no reason to believe I’d work in Los Angeles as a model. I wasn’t a California girl. But I’d learned a lot about my body walking the runway for Halston and Giorgio Sant’Angelo — which had hitherto been a déclassé thing to do. But I loved it. It drew me out of my shell.

Continue reading the main story

PG: Did you start auditioning?

AH: I met Jack Nicholson in the first months I was in L.A., and I knew what I wanted: to be with him. And that happened. For a couple of years, I was watching him work and thinking about his leading ladies. I wished I had this part or that, but nothing much happened. It was difficult because I didn’t want the parts to come because of him. It was kind of back to Dad.

PG: You’d already separated from one strong father.

AH: Oh, I go on looking for them. I always like to have a nice big father figure in the background. And then “Prizzi’s Honor” came around. A producer who worked with my dad sent it to me. I read it overnight and loved it. But he wanted Dad to direct and Jack to co-star. And I thought: Damn! This was supposed to be my passport to independence, but it wasn’t. I said: “There’s no way I’m getting those two tires in a row.” But they loved each other. And it was a great part. That was the difference.

SC: I love you as that character.

AH: That was good, black sheep stuff.

PG: Could you collaborate with your father again, Sofia?

SC: I don’t know. I show him my films before I lock the edit, and he always gives me good insight. But then there are things I don’t agree with, and

AH: He wants you to do what he thinks.

SC: I still feel like a kid with him. We’re not equal collaborators. I admire him, but I feel more comfortable working with my brother, Roman. We’re coming from the same place.

PG: Finding the right collaborator makes me think of your love lives. For a while, you were both part of “it” couples: Anjelica and Jack Nicholson, Sofia and [the Oscar-winning writer and director] Spike Jonze. You couldn’t open a groovy magazine without seeing you. Fun as it looks?

SC: For me, it was fun because he was another creative person. He had this whole world of skateboarders, which was so different from mine. Whenever different people come together, it’s fun to be in the middle of that.

AH: Extremely exciting — and not for the obvious reasons. Those were what caused the problems: all the attention and the paparazzi and the other women. But the people Jack knew and introduced me to, the new landscape that became my life — Mike Nichols, visual artists, Joni Mitchell — hello! It was life changing.

SC: He’s such a charmer.

AH: Jack was at the top of his game and really fun to be with.

PG: Still, you both moved on to quieter relationships.

AH: That’s true. But not necessarily about being with a famous person.

SC: I never thought about my being in a public relationship until you mentioned it. It was an exciting time, but not

PG: Really? In the '90s, I thought: Don’t they ever go to sleep?

SC: Sure, but that’s when you’re in your 20s.

AH: You’re up. You’ve got the energy. You’re at clubs.

SC: It’s just a different time in your life.

PG: Fair point. No parent-teacher conferences back then. Let’s end with memoirs. Why two of them, Anjelica?

AH: Well, I wrote it all at once, 900 pages. My publisher said we’ve got to make this into two books. And there were two separate lives: before L.A. and after L.A. It seemed like a natural punctuation.

SC: Did you keep a journal?

AH: I’d write things down that were pertinent to the way I was feeling, but I didn’t do it day by day. When people started asking: “When are you going to write a book?” I started thinking about it.

PG: Will you write a memoir, Sofia?

SC: I’ve never thought about it.

AH: Too young!

This interview has been edited and condensed.

nytimes.com

Not Plain Jane

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2010

- Messages

- 15,479

- Reaction score

- 844

^ me too. angelica is so beautiful in her own way, just like sofia. nothing typical about either. and the interview is so open and honest. i love how these two wonderful women transcended the male legacy of their family lines too! yes!!

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2010

- Messages

- 102,090

- Reaction score

- 66,992

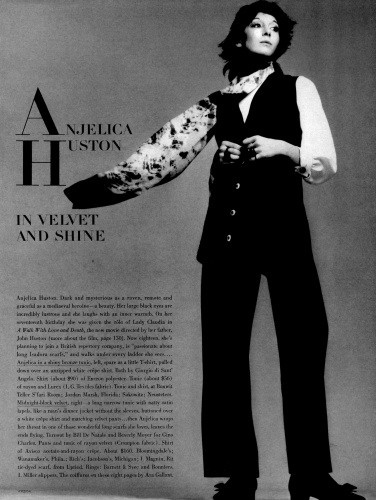

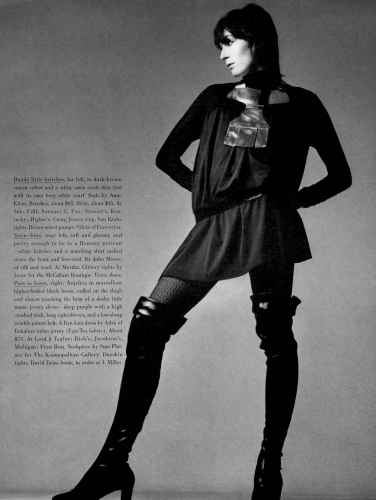

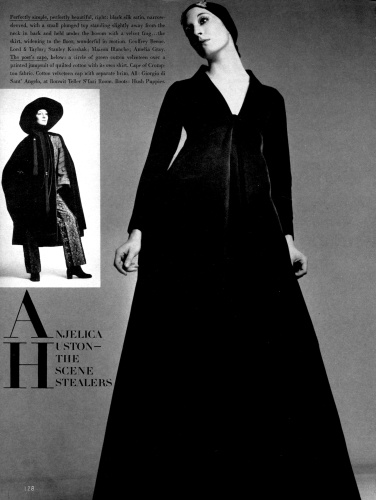

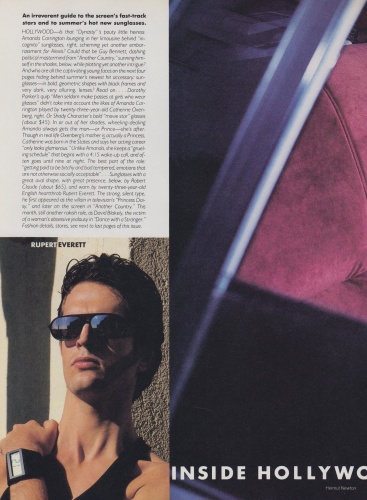

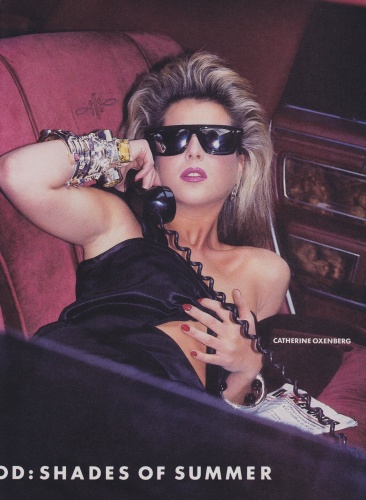

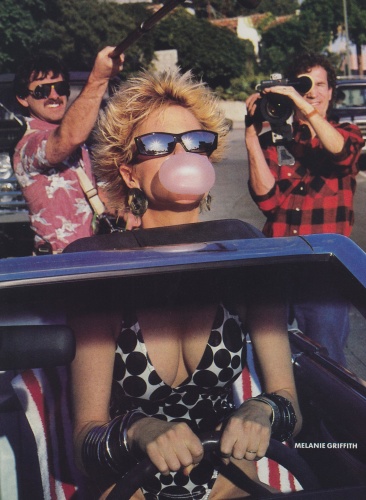

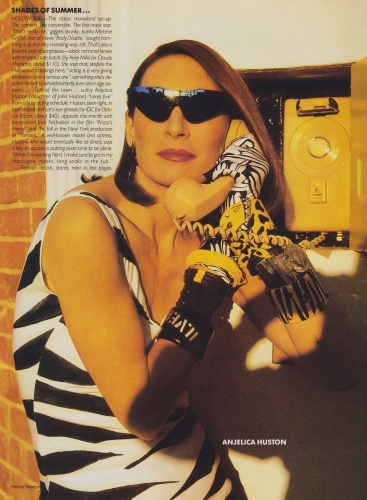

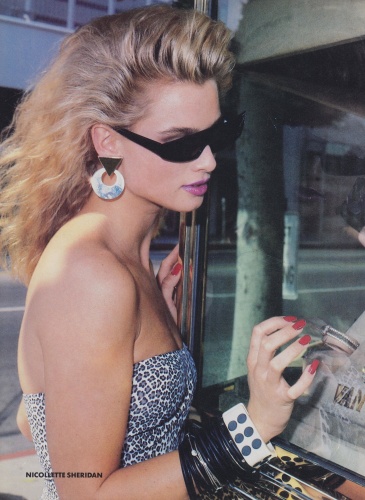

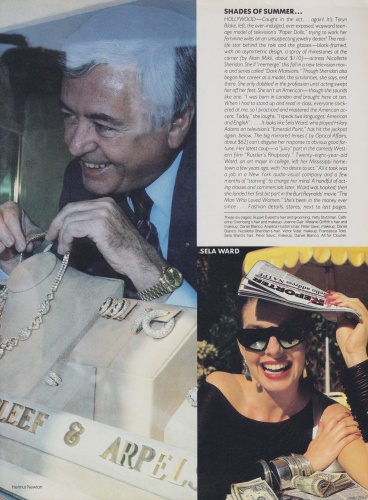

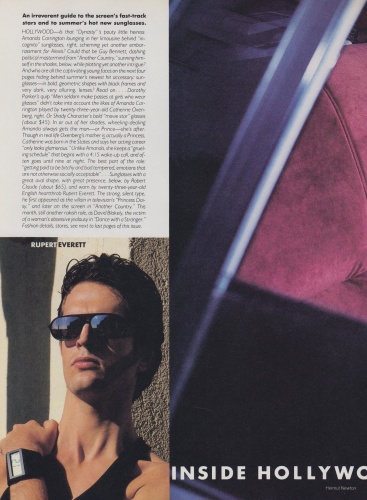

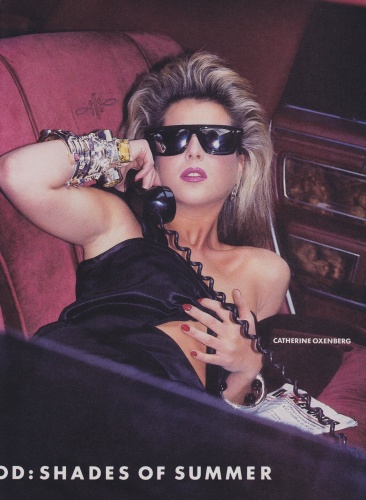

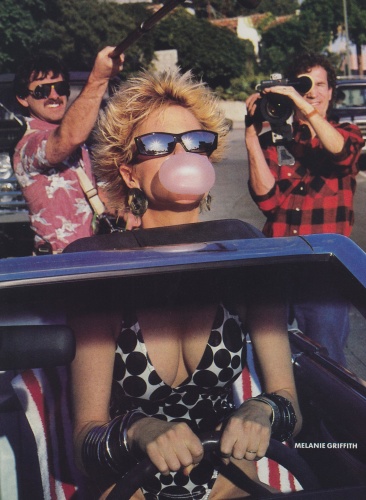

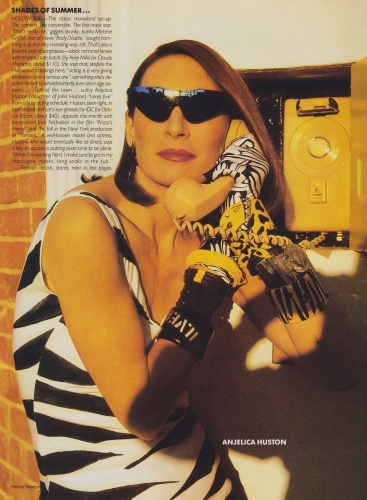

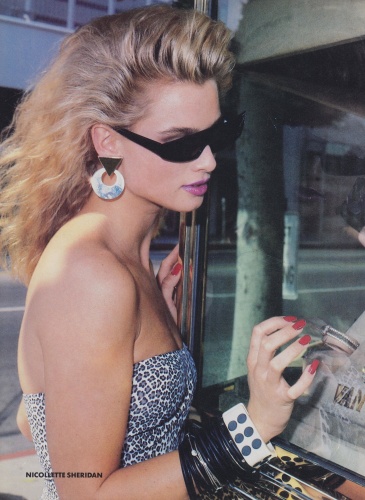

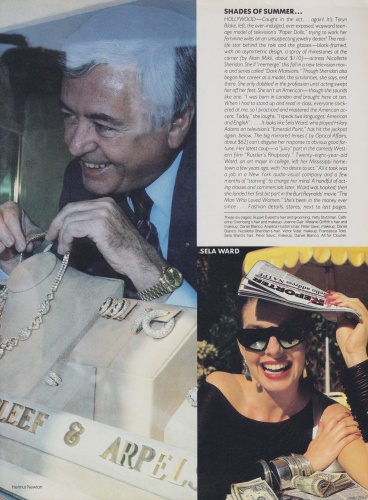

US Vogue June 1985

Inside Hollywood: Shades of Summer

Photographer: Helmut Newton

Editor: Jade Hobson

Hair Styling: Yetty Stutzman, Joanne Gair, Daniel Blanco, Peter Savic, Victor Vidal

Makeup: Joanne Gair, Daniel Blanco, Francesca Tolot

Cast: Rupert Everett, Catherine Oxenberg, Melanie Griffith, Anjelica Huston, Nicolette Sheridan, Sela Ward

Vogue Archive via aracic

Inside Hollywood: Shades of Summer

Photographer: Helmut Newton

Editor: Jade Hobson

Hair Styling: Yetty Stutzman, Joanne Gair, Daniel Blanco, Peter Savic, Victor Vidal

Makeup: Joanne Gair, Daniel Blanco, Francesca Tolot

Cast: Rupert Everett, Catherine Oxenberg, Melanie Griffith, Anjelica Huston, Nicolette Sheridan, Sela Ward

Vogue Archive via aracic

Last edited:

Not Plain Jane

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2010

- Messages

- 15,479

- Reaction score

- 844

thanks for sharing - ha ha, that spread is SO mid-80s.

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 48,027

- Reaction score

- 8,807

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 48,027

- Reaction score

- 8,807

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

New Posts

-

-

Vogue Hong Kong December 2025: Freen Sarocha & Rebecca Patricia Armstrong by BJ Pasqual (4 Viewers)

- Latest: amby

-

-

-