Elle UK - April 2020

TIFFANY NICHOLSON

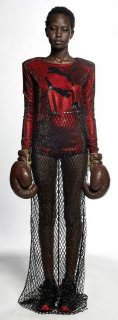

Aweng Chuol: A Thoroughly Modern Supermodel

Aweng Chuol is the supermodel name on everyone's lips... but the story of how she reached the top is the stuff of a Hollywood film script. Here, she shares her incredible story.

AS TOLD TO

HANNAH NATHANSON

10/03/2020

'Hi, welcome to McDonald’s. My name is Aweng. How can I help you?’

The woman stood in front of me. And stared. She was well put together – with manicured hands, long groomed hair – not a typical customer in this quiet branch of the Golden Arches in Sydney’s western suburbs. I stared back at her. ‘Oh my god, you’re beautiful,’ she said. I looked down, embarrassed, then she repeated, ‘You’re beautiful,’ as though in a trance.

I was tired, I’d been working for hours and was about to leave for my shift at the KFC down the road. I had multiple jobs to pay for college. A strong work ethic was something my grandparents, who’d emigrated to Australia from southern Sudan five years previously, instilled in me. Since I’d begun working aged 14, I’d been approached several times by people claiming they could make me a star – mainly alleged Disney agents and model scouts.

I told the woman that my shift was about to end; that she was the last person I would

serve. She didn’t seem flustered by my abruptness, but instead carefully places a business card on the counter. Sliding it towards me she said, ‘Here’s my friend’s card. You’re going to be a superstar. You’ll thank me one day.'

TIFFANY NICHOLSON

Two weeks later, I was on a plane to Paris to walk for one of the most exclusive fashion houses:

Vetements. That evening, after my work shifts, I’d given the card to my mother. Flattered as I had been by all the attention before, it had never been the right time – I was set on finishing school and going to university to study law, join the debating team and maybe get my heart broken along the way. But things were different this time. I had just turned 18 and was in my second year of university. I was in control of my own schedule. My mother was the one who pushed me into following up the offer of the woman in McDonald’s. She was tired of having a superstar daughter who didn’t want to be a superstar. It turned out the friend of the woman who’d come into McDonald’s was a model agent. After I met her, she immediately made me an offer: if she could fly me out of Australia within two weeks, then she would sign me to her agency. If she couldn’t, then I could get on with my regular life.

It was surreal to be leaving home on my own – up until that point I’d never even bothered to get my Australian passport. I’m the eldest of 12 children, so it felt like I was abandoning my siblings, some of whom were like my own children. My ticket was only one way, so no one – including me – knew whether I’d be coming back. I arrived at Paris Charles de Gaulle airport in the freezing cold one February morning and looked around in total disbelief as crowds of people swirled around me. The last time I’d seen this many people in one place was in the refugee camp of Kakuma

TIFFANY NICHOLSON

Iwas born in Kakuma, a refugee camp in the northwestern region of Kenya, which was a haven for anyone from east Africa trying to find safety during the civil war in Sudan. Over the years, it had grown to accommodate tens of thousands of refugees, as civil war raged in neighbouring southern Sudan and political instability continued in Ethiopia and Somalia. Kakuma has become well-known in the fashion world because a lot of models were born or raised there, including Halima Aden and Adut Akech.

Since I'd begun working aged 14, I'd been approached by people claiming they could make me a star

My mum arrived in Kakuma with her entire family in 1996, from what is now recognised as South Sudan. Two years later, she fell pregnant with me. The daughter of a pastor, her pregnancy at age 15 was not well received. The advice she was given, like many girls her age, was to abort the child as there was no way they would be able to raise children in that environment. There were certain leaves growing in a nearby field that could be used to ‘wash out’ the child, without any pain, by bringing about labour prematurely.

My grandfather asked my mother to walk to the field where they grew the leaves. When she arrived there were several young girls sat eating these ‘magical’ leaves. My mum still cries when she recalls the scene today. The message was clear: if you keep this child, it will suffer, and so will you. My mum decided there and then that she wouldn’t eat the leaves; she was met with a chorus of women asking her what in god’s name she thought the child would eat. Her reply was simple: the child would eat whatever she ate. When my grandfather heard the news that she hadn’t eaten the leaves, he was irate. He said it would bring shame on the family and that it was the wrong decision – he was more worried about his reputation than about his daughter.

TIFFANY NICHOLSON

For most of my first year, I had no name. My grandparents wanted me to be called Atonge, but my mum was set on Aweng. Everyone wanted something different for me, so I was just called ‘Baby’ and then ‘Girl’ for the first year of my life. I was brought up to know that I was beautiful, especially by my mother. At the back of my mind, I always had an idea of my beauty, but it wasn’t until the end of my teens that I really grasped how striking I was. With the same rebellion my mother had shown by keeping me, she snuck Aweng onto my birth certificate without telling anybody. And that was that. ‘Aweng’ translates as ‘cow’ in our culture and cows are sacred, so there is a deep significance to my name.

People assume I have bad memories from growing up in Kakuma, but the opposite is true. It was home to me – as homely as you could make a one- bedroom camp with six siblings and a pregnant mother. Of course, it was traumatic in the sense that there was a civil war in Sudan, but I was raised without anything being hidden from me. Despite all the blood and all the running, my parents were always honest with me.

I was brought up to know that I was beautiful, especially by my mother

I was about to turn eight when my grandfather had finally had enough of all the running away and insisted we move to Australia, where he felt the climate would suit us better than the US. And so we left Kakuma. My mum was pregnant when she travelled alone across the world with six children under the age of eight. She was 22. My father refused to come with us – he’d been a child soldier and wanted to die in Sudan – so she left the only man she’d ever known to start a new life on the other side of the world, and I watched it happen. I watched the phone calls from Kakuma to Australia, I watched the phone being thrown in anger as my parents rowed about going. I watched as another phone was brought, so we could get in touch with my grandfather who was already in Australia. As young as I was, I was watching it all. It was hard on everyone.

TIFFANY NICHOLSON

When we arrived in Sydney, my mother never changed the script of our childhood. I grew up in a South Sudanese community, and had a happy childhood integrating well into this new Australian world.

So when I stood there, 10 years later, in a white studio in front of

Demna Gvasalia [the founder of Vetements], meeting his entire team, I didn’t feel nervous or scared. In fact, I felt at home. As soon as I walked in, he said, ‘Oh, Miss Australia is here!’ It immediately broke the ice. There was a lot of laughter as we did a fitting for the show that evening. I really had no time to be nervous. Everyone kept telling me to breathe, but the first time I stepped out onto the catwalk, for the Vetements AW18 show, all I could think was, I have a law assignment due in two hours! But right then I knew I had to focus on walking. I wasn’t used to walking like a model and my velvet trousers went all the way over my shoes, so I constantly felt as though I was about to fall.

Walking exclusively for Vetements was just the beginning. After that first show, I raced back to my hotel, finished my law assignment, sent it in and then fell asleep. I woke to news that I’d been signed by agencies in Paris, Milan, New York and London, all in one night. Since then I’ve seen the world, shooting with industry legends and working with fashion houses such as

Burberry.

TIFFANY NICHOLSON

Fashion has always been an art form for me; I’m in it for the art. I’ve always admired how someone could sit down with a plain white piece of paper and come back with all this colour and shape. One of my favourite designers has always been

Alexander McQueen – I love the way he embodied a woman’s figure. As a child, I never knew the names of all the biggest people in fashion, but when I saw a photo that

Peter Lindbergh took of

Kate Moss in a magazine, I knew that was beauty and I cut it out and stuck it on my bedroom wall.

As I’ve settled into the industry, what I love most is that it gets reborn each season. But I never imagined myself actually working as a model. I thought I’d do one show, then go home and finish university, and that would be it. So to have options, and to be shot by someone like

Nick Knight – who’s always been one of my top photographers - is still surreal. When they said, ‘Nick Knight wants you,’ I replied, ‘I’m on my way!’

Above everything else, it’s been important to be honest to myself and to the world. I never wanted my story to be all about the refugee girl who became a supermodel overnight. I wanted to shape my own narrative. After all, I worked to make the best out of the situation. Most people who came from Kakuma have a different perspective of the camp. For some, it wasn’t the safe haven I saw it as, but that is their story, for them to tell. For me, I found an escape from reality. You can’t change the past – all you can do is grow from it.

This article appears in the April 2020 edition of ELLE UK.

Interview Magazine - March 2020

polaroid

models