Self-portrait, with a detail from artist Albrecht Dürer’s Young Hare, 1502

Brigitte Niedermair puts fashion in focus at Venice retrospective

Self-portrait, with a detail from artist Albrecht Dürer’s Young Hare, 1502

Brigitte Niedermair puts fashion in focus at Venice retrospective

BY TOM SEYMOUR

Brigitte Niedermair is known for portraits juxtaposing female models with the heads of farm animals found in local butchers’ shops, or for arranging fashion-clad legs and hips to correspond to the curve of carrots found in her vegetable patch, or for counterpointing a couture bodice with a still-living clam.

Working with a 4x5 large-format camera, she will spend hours constructing her images before capturing each tableau with just a handful of shots. Niedermair, then, is a unique proposition among makers of contemporary fashion imagery. And perhaps uniquely ambitious.

Ahead of ‘Brigitte Niedermair: Me and Fashion 1996-2018’ which opens today at the Museum of Palazzo Mocenigo, as part of the

Venice Biennale, Wallpaper* spoke to the photographer at her home in the Italian Alpine town of Merano. ‘I don’t want cool, I don’t want funny,’ she says. ‘I want to reach eternity with my images.’ The exhibition showcases more than 30 images and still lifes dedicated to fashion, which interplay with the majestic 17th and 18th century decoration of the museum’s first floor rooms. For the show, Niedermair removed a selection of paintings from the Moceningo collection and replaced them with her own images.

Charlotte Cotton, who is curating the Venice exhibition, says eternity may be in reach: ‘Fashion photography has had periods in history where it has successfully responded to what’s happening in the world [and] created larger, iconic and lasting imagery. Brigitte differentiated herself by continuing to work in that lineage.’

Niedermair was born in Merano in 1971. She dropped out of a photography course before moving to Milan and then on to Miami. Throughout that period, she would travel to New York and Los Angeles, working as a casting director in the film and advertising industries, before assisting directors on larger shoots. She got to know many of the models and actresses on the casting call circuit and began taking monochrome portraits of them, borrowing studios usually reserved for rigorously commercial shoots.

‘There were no other women in fashion photography in Italy,’ Niedermair says. ‘I was the only one, so there was no cultural reference for me. It was very, very difficult for me to survive in the beginning. I realised that success is about doing it not once or twice, but for a long period. I had to believe and trust in myself.’

‘You get the sense that she has been extremely resilient and very focused in order to make the kind of work she wants to make,’ Cotton says.

Some might have chosen to keep on with the jet-setting lifestyle and the big-money seductions of the film and advertising industries. But after a decade or two on the road, Niedermair made the decision to return home to Merano.

‘There’s a cultural strength to her character,’ Cotton says. ‘She doesn’t come from one of the major cities that we often associate with the fashion business, but that gives her this openness and generosity, and a very grounded sensibility. She’s pro-women, and she’s genuinely speaking to and for women. That remains a very prized and underrated quality within fashion.’

‘Everything was born in Merano for me,’ Niedermair says. ‘So my art and fashion practice closely relates to my private life here. I grew up surrounded by these mountains – they’re immovable, they look at you, and you look at them, and they’re connected to the sky. It made me care for precise images. And it made me care for light, when there’s so much darkness and ugliness.

‘Fashion is an interesting playground,’ she says. ‘But my art is more spiritual. It’s important for me always to reassess and reread something from the past. All of my fashion ideas start from looking at a classical

painting.’

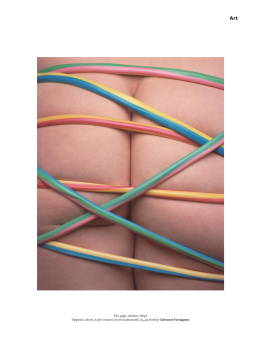

That relationship to nature and the history of art is illustrated in the pitch that Wallpaper* fashion content director Isabelle Kountoure received from Niedermair in the spring of 2014. ‘She suggested we orientate the shoot around the root vegetables she had grown in her garden in Merano,’ Kountoure says. ‘They’re the kind of misshapen, “imperfect” vegetables our supermarkets would routinely reject. But she saw something in them – and she was able to envision how they might correlate to the female form.’

The idea eventually became the series

Unexpected Sculptures, a collaboration between Kountoure, Niedermair and artist Lucy McRae. The images were first revealed in Wallpaper’s September 2014 issue – one of eight cover stories that Niedermair has shot for Wallpaper*.

‘In someone else’s hands, it could have been a lame joke,’ Cotton says. ‘But the images are so beautiful. Brigitte gave these gnarly vegetables the same treatment as a Constantin Brâncusi scuplture. It’s such a wry commentary on what imagery in the commercial sector can achieve. But then, when they’re placed alongside her representations of the female form, there’s something brilliantly sexual about them.’

In March 2017,

Unexpected Sculptures was followed up with

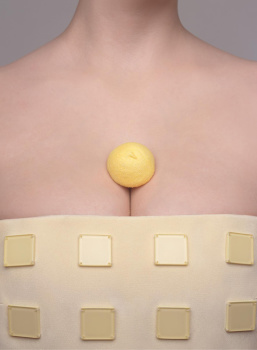

Shape Shifters, a series that juxtaposed the aesthetics of rustic shellfish with designer couture. Hard-shell clams, oysters and sea urchins – ‘which continued to move during the shoot’, Kountoure says – were photographed alongside bustiers from

Louis Vuitton, dresses from Celine and coats from Kenzo. ‘Brigitte took these things that are about to decay, and made them incredibly beautiful and climatic,’ Cotton says. ‘She really understands how to make very ordinary things suddenly seem iconic, and that still has a real edge to it in fashion

Wallpaper