-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

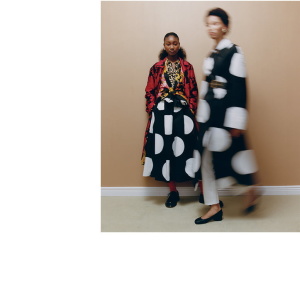

Nordstrom Spring 2020

https://n.nordstrommedia.com/id/96876bc9-14de-4d4c-ac76-e5478863aa03.mp4?h=0&w=0

shop.nordstrom.com/c/spring-fashion?jid=j011192-11886&cm_sp=merch designer_11886_j011192

designer_11886_j011192 freelayout_all_p99_info#video-play

freelayout_all_p99_info#video-play

https://n.nordstrommedia.com/id/96876bc9-14de-4d4c-ac76-e5478863aa03.mp4?h=0&w=0

shop.nordstrom.com/c/spring-fashion?jid=j011192-11886&cm_sp=merch

designer_11886_j011192

designer_11886_j011192 freelayout_all_p99_info#video-play

freelayout_all_p99_info#video-playsimplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

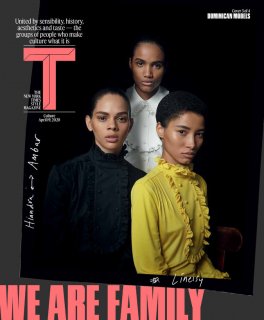

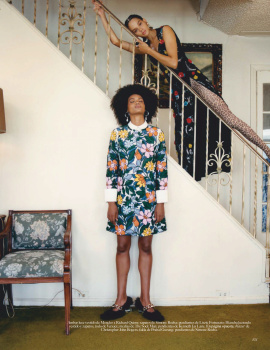

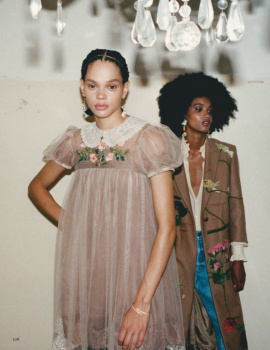

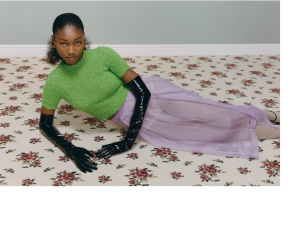

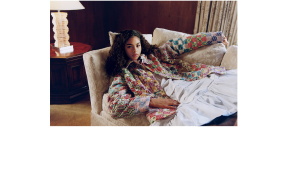

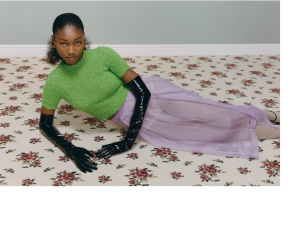

THE BEAUTIES

How a new generation of Dominican models has come to define the

runways — and continues to shape our definition of what beauty looks like.

BY CONCEPCIÓN DE LEÓN

April 13, 2020

Video:

Dominican Models on the Rise

The women talk about finding success in the fashion world and redefining notions of beauty in their home country. Video by Aurélien Heilbronn

WHEN LICETT MORILLO, now 23, left the Dominican Republic for Milan in 2018, she had little time for self-doubt. A month earlier, on the streets of Santo Domingo, her stately face had caught the eye of a modeling scout as she rushed to her immersive English class. Shortly after, Morillo landed her first casting call for Prada. There, surrounded by hundreds of other girls, she recalled thinking, “No, this isn’t going to work.”

But it did. Morillo was selected to close the spring 2019 Prada show — an honor — and over the last few years, her rise has been replicated many times, as Dominican (and Dominican-American) models such as Annibelis Baez, Luisana González, Melanie Perez and Dilone have appeared on runway after runway, from Valentino to Saint Laurent. They are one part of a greater industrywide shift: In the past fall season alone, nearly 40 percent of models who walked in London, Milan and Paris were women of color, up from 17 percent in 2014, when the fashion news site the Fashion Spot began tracking runway racial diversity. In New York, nearly 46 percent of the models walking the runway were women of color.

Fashion has long elevated (or in some cases, fetishized) certain ethnic groups, whose sudden prominence and ubiquity are usually attributable to a single standout face. In the aughts, the Russian Natalia Vodianova was part of a wave of former Eastern Bloc models celebrated for their angular features and near translucent skin; the growing economic might of China helped give rise to Liu Wen and Fei Fei Sun. Every phase was reductive in its own way. But the idea of blackness and beauty has always been particularly so; black models of the ’70s, for example, were generally favored if they were light-skinned or possessed seemingly European features. That definition expanded in the ’80s and ’90s with the arrival of the British-Jamaican Naomi Campbell and the South Sudanese-British Alek Wek, but there were rarely more than a few representatives. “Diversity” came with a strict quota attached.

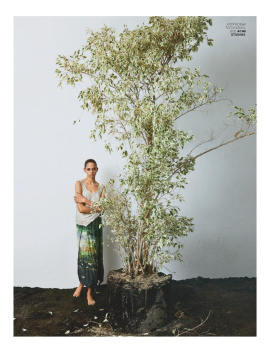

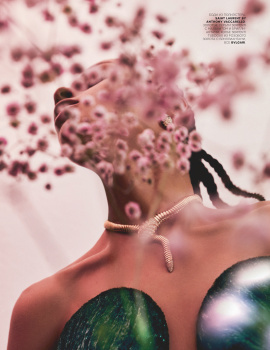

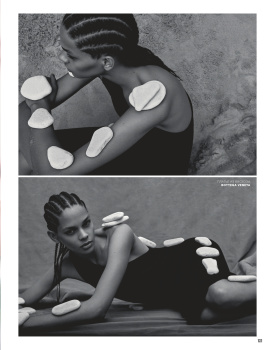

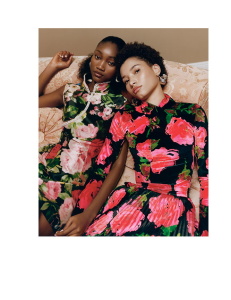

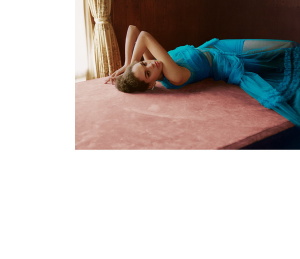

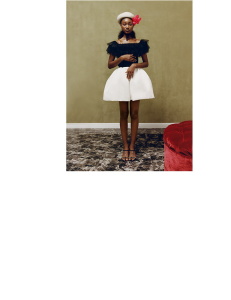

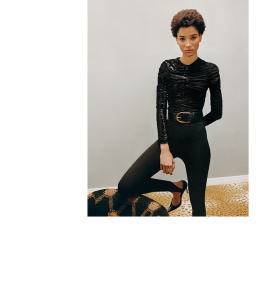

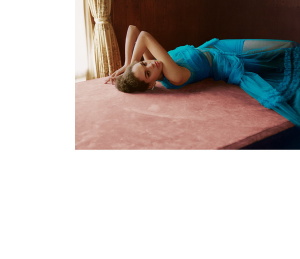

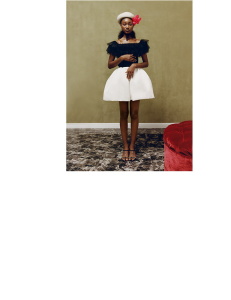

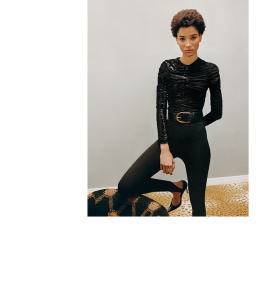

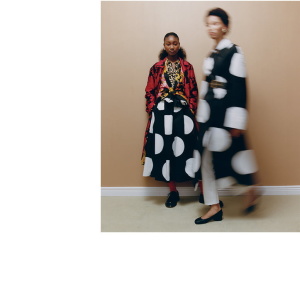

Clockwise from top left: MARTHA MASSIEL in a Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello top, $2,690, and shorts, $5,490, ysl.com; LICETT MORILLO in a Prada top, $1,260, and skirt, $1,830, prada.com; MELANIE PEREZ in a Chanel top, $8,000, (800) 550-0005, and Louis Vuitton skirt, price on request, louisvuitton.com; LISSANDRA BLANCO in a Prada top, $1,260, and skirt, $2,110; ANNIBELIS BAEZ in a Louis Vuitton dress, price on request; LUISANA GONZÁLEZ in a Celine by Hedi Slimane top, $2,450, (212) 226-8001, Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello shorts, $950, and Chanel shoes, $850; AMBAR CRISTAL in a Prada dress, $1,910, tights, $270, and shoes, price on request; HIANDRA MARTINEZ in a Prada dress, $1,910, tights, $495, and shoes, price on request; LINEISY MONTERO in a Prada dress, $2,110, tights, $270, and shoes, price on request; and ANYELINA ROSA in a Celine by Hedi Slimane top, $1,050, Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello shorts, $950, and Chanel shoes, $850. Photographed at Little Grand Studio in Aubervilliers, France, on Jan. 24, 2020. Photograph by Willy Vanderperre. Styled by Olivier Rizzo

Today, black African models of very different skin, hair and appearance — from Adesuwa Aighewi, an American who has Thai, Chinese and Nigerian roots, and Anok Yai, an American born in present-day South Sudan, to the South Sudanese-Australian Adut Akech and the hijab-wearing Somali (by way of Des Moines) Ugbad Abdi — reflect, in their diversity of presentation and origins, a more authentic identity in fashion. But Latin America’s own racial and ethnic heterogeneity has failed to receive the same treatment. The surge of Brazilian models in the 1990s, for example, almost wholly favored white and tan-complexioned models like Gisele Bündchen and Adriana Lima. Which is why the women coming out of the Dominican Republic, most of whom are Afro-Latinas, finally offer a more expansive view of Latin America’s racial diversity.

WHILE MODELS LIKE Morillo have come to represent social progressiveness in the American and European fashion worlds, their identity in the Dominican Republic (and elsewhere in Latin America) is more complex. The Dominican Republic was colonized by the Spanish in the 15th century and is where the first Africans were enslaved in the New World, but it was once the land of the Taíno indigenous group, who, though largely wiped out by the Spanish, are still inseparable from the country’s mythos and history. Dominicans have always been proud of this inherent mestizaje, or “mixed ethnicity.” “In the Dominican Republic,” said Anyelina Rosa, 19, “we don’t use that language of whether we’re white or black, because my color is very common and normal.” Nearly 90 percent of the island’s population is either mixed race or black (only about 13 percent identify as white) according to a recent population survey, and though most Americans or Europeans would label these models as black, a person in the Dominican Republic might choose to describe them as morena, trigueña, jabada or india — all common words used to denote different gradations of blackness but not necessarily blackness itself. To some extent, too, the nation’s cultural identity was forged in opposition to Haiti, the decidedly black country on the other side of the island, which briefly held Santo Domingo under its control in the 1800s and has historically been derided by the Dominican ruling class, to the extent that Dominicans celebrate their Independence Day on the day of secession from Haiti, rather than Spain. (Never mind that it was under French and Haitian rule that the abolition of slavery was achieved twice — first in 1801, and then later in 1822 — or that traces of the Dominican Republic’s African roots were already present in nearly all of its culture.)

Unsurprisingly, this layered colonial past has also complicated Dominicans’ own sense of what beauty looks like and is. Several of the models say, for instance, that they struggled with self-image in their home country, which, like much of the rest of the world, favors fair skin, long, straight hair and European features — but also a certain body type my own cousins in Santo Domingo call un cuerpo tropical, a voluptuous figure that is generally considered much more desirable than thinness. Efforts to fight against anti-black beauty standards have intensified in recent years, but many women are still strongly discouraged from wearing naturally curly or kinky hair to school or work because it’s widely viewed as unkempt and inelegant. This was true for Rosa, who, when she lived in the Dominican Republic, relaxed her hair; she now usually wears it in cornrows or in an Afro. Originally rejected by local designers, her international work in fashion has broadened her perceptions of beauty. “Now I have self-love,” she said. “I don’t say, ‘I can’t,’ that I’m ugly, that they won’t pick me.”

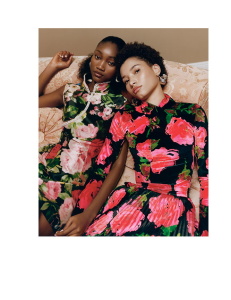

One of four covers of T’s April 19 Culture issue. Clockwise from top: AMBAR CRISTAL, in a Prada dress, $1,910; LINEISY MONTERO in a Prada dress, $2,110; and HIANDRA MARTINEZ in a Prada dress, $1,910. Photograph by Willy Vanderperre. Styled by Olivier Rizzo

It is perhaps ironic that an industry often responsible for perpetuating unrealistic beauty standards is also helping people embrace traits they were long told were undesirable. It’s both a reflection of the evolution of fashion, the ways in which its understanding of inclusivity — not just in matters of race but in gender, sexuality, age and size — has expanded, as well as the specific value of a global black diaspora in elevating conversations around the black, post-colonialist experience. Even if these models are not necessarily labeled black by their compatriots, to the rest of the world, and in the context of an international diaspora, they are — and their success in the fashion world is a boon to representation in general. Their presence is having an effect in the Dominican Republic, too, where local media regularly boasts about their successes, even while revealing their biases. In one TV interview, right after Morillo’s Prada debut, a host asked her if she had felt beautiful before becoming a model in a way that seemed to imply she shouldn’t have. But Morillo simply smiled and said, “Yes. My self-esteem is very high.” Last September, Vogue Latin America featured four Afro-Dominican models, including Morillo and Baez, on their cover. Lineisy Montero, at 24, arguably the best-known of this generation of Dominican models, had already been featured on several magazine covers, having become an industry favorite in 2015 when she debuted on the Prada runway wearing a short, immaculately trimmed Afro. It’s easy to be skeptical of racial progress when only a singular person is celebrated as representative of broader institutional shifts. But in this case, these models have created a space for change because of their plurality. “That so many Dominican girls are here is synonymous with improvement,” Morillo said. “Ninety percent of us are from humble families, and that we’re here giving our best, it fills me with pride.”

Not pictured: Dilone, Yorgelis Marte and Sculy Mejia Escobosa.

Concepción de León is a reporter covering literary news and culture for The New York Times. Willy Vanderperre’s most recent show, “Hurt, Burn, Ruin and More,” opened in March at London’s 180 The Strand. Models: Martha Massiel, Licett Morillo and Lissandra Blanco at IMG Model Management; Melanie Perez and Anyelina Rosa at Society Model Management; Annibelis Baez at DNA Model Management; and Lineisy Montero, Hiandra Martinez, Ambar Cristal and Luisana González at Next Model Management. Hair by Anthony Turner at Streeters. Makeup by Lynsey Alexander at Streeters. Casting by Nicola Kast at Webber Represents. Manicure: Liza Papass. Producer: Entrée Libre.

Last edited:

Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,582

- Reaction score

- 20,805

simplylovely

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 30, 2006

- Messages

- 29,485

- Reaction score

- 1,180

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)