DosViolines

far from home...

- Joined

- Aug 21, 2005

- Messages

- 3,212

- Reaction score

- 12

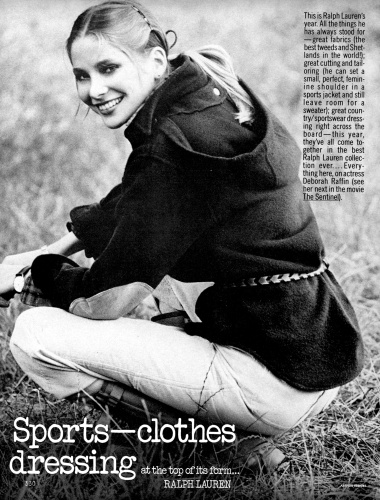

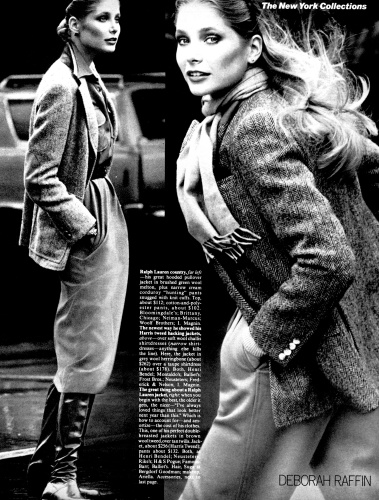

nytimes

More photos >>August 26, 2007

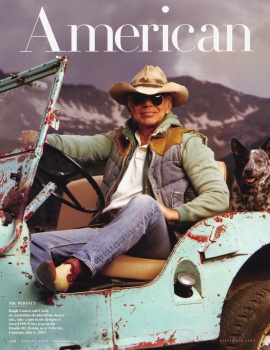

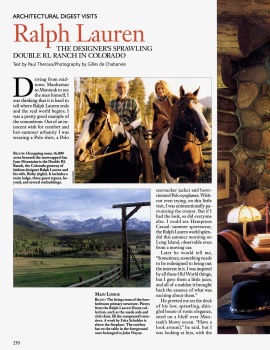

Captain America

By GUY TREBAY

If Bush America appears to be tanking — as the Iraqi war grinds into its fifth year and the universal sympathy vote that was ours after 9/11 has soured into a sort of universal distaste — Polo America is having a banner year. This began to become clear to me not long ago, as I walked across Red Square in Moscow. Spotting a young student wearing board shorts emblazoned with the Stars and Stripes, I stopped him to inquire what this sanctified emblem of Jeffersonian democracy signified in his mind. “Ralph Lauren brand,” he said flatly and moved on.

The truth is, things do not seem all that different in Paris, Milan or Tokyo, as I found on a recent tour through those cities, where I was constantly startled to see people costumed as if they were auditioning for “Love Story” or “The Summer of ’42” or an Independence Day parade. Ralph Lauren, of course, is far from alone in having divined a burgeoning appetite in the marketplace for classic American styles or marketing to it. At the recent men’s-wear shows in Italy, every designer who was not exhibiting Zouave pants or boiler suits claimed Steve McQueen as an influence. And it cannot be an accident that the Grimaldis of Monaco have turned to marketing the cool patrician looks of their Philadelphia-born mother, the ultra-American ice princess Grace, with a museum retrospective and a lavish catalog, in an effort to pep up their kitsch principality; or that Tommy Hilfiger now operates a store in Paris to sell the stuff he always refers to as “preppy with a twist”; or that even Brooks Brothers has inaugurated an outpost along a stretch of the super-modish Rue St.-Honoré in Paris. How anomalous it seemed when I first walked down this Right Bank street, past the toxically hip Hôtel Costes and the usual cluster of skinny boys in faux-hawks and Dior jeans, only to come upon a storefront of headless mannequins clad in the kind of staid jackets that instantly evoke “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit.” That was last year, I reckon. Now half the men in Paris seem to be dressing as if they’d decided to change their names from Thierry to Biff.

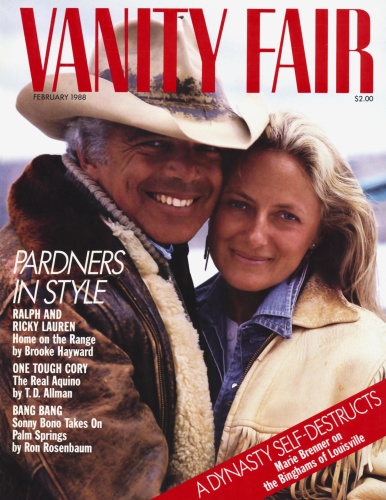

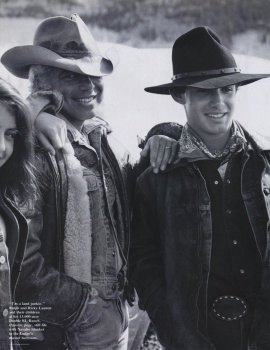

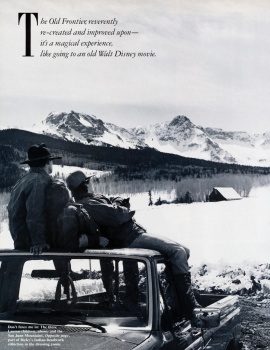

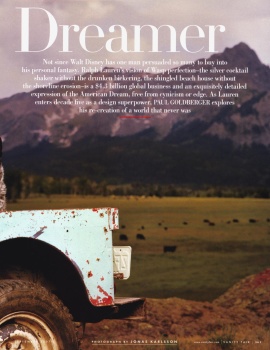

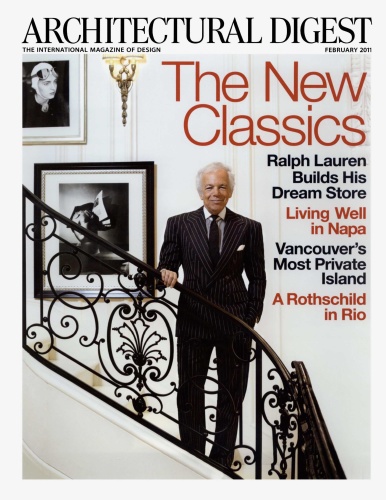

Still, no other designer has approached Ralph Lauren in his capacity for exploiting a certain kind of Americana. It was Lauren, after all, who went from designing a simple four-inch necktie for Beau Brummel in the late 1960s to colonizing vast sartorial hunks of American high society and transforming the tweaked results into a $13.5 billion publicly traded business whose logo, a jaunty equestrian with a cocked polo mallet, is almost as recognizable in certain places as the American flag. Much as Walt Disney did before him using another cluster of homegrown symbols, Lauren has recently expanded his retailing theme parks to include outposts across the globe; in the past several years alone, he has opened showy flagships in Milan, Tokyo and, most recently, Moscow, all part of a campaign to expand and conquer, to turn Ralph Lauren America into Planet Ralph.

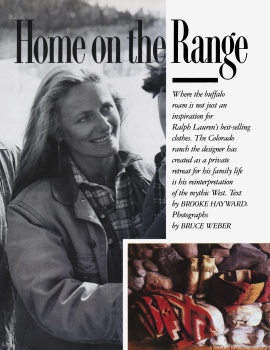

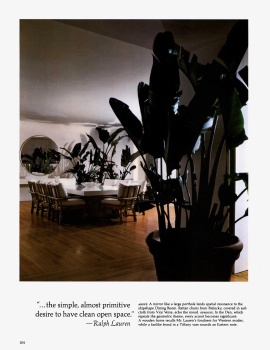

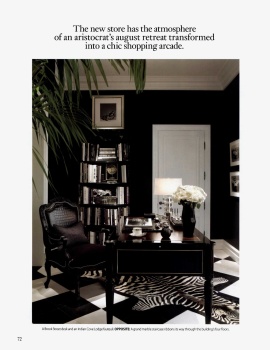

“I’m not designing clothes, I’m creating a world,” Lauren once remarked, and that world, manufactured from whole cloth, is as organized and as tightly scripted as anything ever devised by Uncle Walt. Yet, where Disney drew his inspiration from archetypes as old as human history, Ralph Lauren has kept his vision strictly focused on narratives of class. His genius, frequently noted, lies in his ability to exploit a longing most of us feel to elevate our ordinary bourgeois existence and adapt it, at least superficially, to resemble the more seductive contours of our social betters. It is far from a secret that Lauren lures consumers into a dreamscape populated by fair-skinned, fine-boned people with the “kind of attractiveness,” to quote the class-obsessed Italian novelist Alessandro Piperno, “that is usually the prerogative of high-ranking Gentiles.” He installs us, through his advertising and his retail imagery, in baronial manor houses with chintz-upholstered drawing rooms hung with ancestral portraits and littered with Chinese vases of massed flowers. From somewhere beyond the pillared porch in Lauren’s West Egg, there comes a sound of tinkling laughter.

A croquet game is underway. Bruce Weber, the house photographer, is on the baize lawn snapping pictures. Slip on a Polo shirt. You may be asked into the frame.

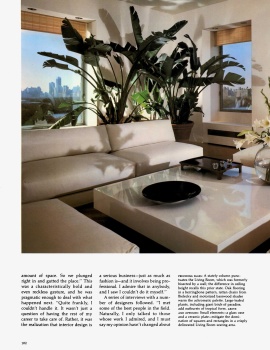

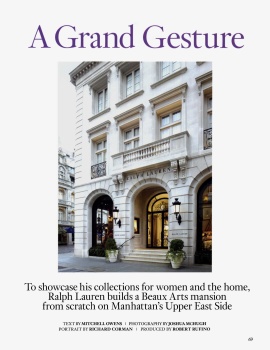

This illusion is given physical form at the flagship stores, which defined the designer store as tourist destination long before Louis Vuitton refurbished its vast 20,000-square-foot theme park on the Champs-Ãlysées in 2005. “I’ve always thought of the collections and the stores like movies or novels,” Lauren told me not long ago as we sat in his New York headquarters, located in a Midtown high-rise whose generic lobby and elevator give little indication of the mahogany-paneled “clubhouse” that lies beyond the office door. Not surprisingly, Lauren’s sanctum is appointed to resemble an annex of his most celebrated retail outpost, the former Rhinelander Mansion on Madison Avenue. That store, which opened in 1986, is the Anglophile template on which the others — on Bond Street in London, the Place de la Madeleine in Paris, the Via Montenapoleone in Milan, Omotesando in Tokyo and Tretyakovsky Passage in Moscow — are based.

Wearing a tan summer suit nipped to accentuate his jogging-fit form, he beckoned a visitor into an office that resembled the room of a spoiled but industrious teenager. There was furniture inspired by Mies van der Rohe and other celebrated 20th-century designers. There were model planes and cars that reflected his passion for collecting vintage automobiles. There were massed fresh flowers and a mélange of photographic and painted images meant to bespeak a cultivated and eclectic eye. Whether he chose the pictures himself is no more the point than the particular fashions of any given season. “It’s not the styles that matter so much,” Lauren said. It’s the script.

By now the visual idiom of Ralph Lauren’s world is as codified and seamless as a blueprint of Epcot Center, all underground passages and concealed machinery. That it is a formula but not schtick owes a lot to the savvy of his corporate design team — headed by Alfredo Paredes, a behind-the-scenes force and himself the son of Cuban immigrants — in conjuring the image of the Polo Ralph Lauren Corporation for more than two decades.

Wherever one visits a Ralph Lauren store, there will of course be those same Chinese vases of massed flowers and pictures of elegant hunting swells. What changes in each is the intensity, the quality and the historical and mnemonic dimensions of the carefully assembled accretions, minutely calibrated in each new market to suit the local levels of expectations and taste.

So it is that, in the 24,000-square-foot Tokyo store whose “neo-Classical” limestone exterior obscures its origins as a utility company, the Japanese “voraciousness for luxury,” as Lauren put it, is richly indulged with sweeping marble staircases; beveled mirrors inset with flat-screen TVs showing footage of Lauren’s runway shows; Persian rugs; benches upholstered in Navajo blankets; Pueblo pottery; framed images of Hollywood stars and louche but natty jazz musicians; and paintings of somebody’s comely ancestors, nobody really cares whose.

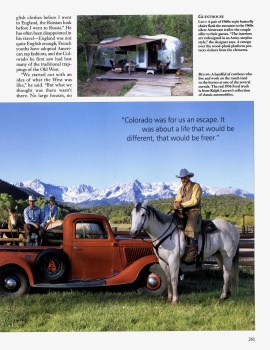

“American luxury is about a sensibility and an approach to life,” Lauren told me. “It’s about developing the world you see in your imagination and using that to create an environment of comfort and ease.” The world Lauren saw in his imagination and has since conjured so successfully for domestic and foreign consumption is at some remove from the one in which he was born 67 years ago as Ralph Lifschitz, and it was distinctly at odds with the reality of growing up in a four-room apartment overlooking Mosholu Parkway in the Bronx, where he was raised by Ashkenazi Jews who fled Russia in the early 20th century. “I was always inspired by those kind of prep-school people and their clothes,” he told me. “By classic things, by the way those people looked and dressed. Maybe because I didn’t have it, I always reached for it.”

Somehow, his accomplishment as a purveyor of the trappings of comfort and ease gains both pathos and distinction when considered in light of a not-always-subtle anti-Semitism that has dogged him throughout his career — the haunting sense that, as the writer Holly Brubach once noted in The Atlantic, he is seen by some as “a play actor, a Jew pretending to the life of the landed gentry.” (The late socialite C. Z. Guest once quipped to me that Ralph Lauren probably owed her social-cohort royalties.)

If nothing else, mimicking the customs and adapting the clothes of the upper class has been good business for Lauren, who was recently named the men’s-wear designer of the year by the Council of Fashion Designers of America and whose brand was recently identified in a consumer survey as one of the world’s most recognizable and desirable. For the last decade, the designer has been buying back many of the estimated 350 licenses under which his products were manufactured in order to consolidate the image of the publicly traded company, of which he has the controlling interest. “Everything I do, everything I’ve ever done, is about what I love and the taste level I believe in,” he told me. “There’s a lot of emotion behind the brand.”

Certainly the decision to open a flagship in Russia had its emotional implications for the designer. “You know, his parents left Russia to go to America,” explained Fabio Mancone, a senior vice president of Polo Ralph Lauren’s European operations. Lauren’s newest Russian store, one of two there, opened in May and occupies three stories of a prime corner on Tretyakovsky Passage, a Rodeo Drive-style confection built around the shells of two 19th-century buildings on a cobbled alley near the Kremlin. If Lauren’s late parents, Frank and Freda, would find little else recognizable in contemporary Russia, surely they would have had no problem comprehending what Mancone characterized as a “hunger there to make it, a hunger for money, for success.”

Alongside Tiffany & Company, Prada and Bentley Motors, Ralph Lauren is now available to satisfy the appetites and evolving tastes of the Russian oligarchs so densely concentrated that Moscow has the highest percentage of billionaires of any capital in the world.

“We sold 17 crocodile Ricky bags” — at up to $20,000 each — “on opening day,” said Alla Verber, a vice president of the Mercury Group, the developers of Tretyakovsky Passage and one of Russia’s foremost importers of luxury goods. “The world still makes fun of Russian people with this idea of either old babushkas or women in high heels and Versace,” she added. “But don’t forget, for 70 years, Russians didn’t have the opportunity to buy anything. It wasn’t around.” After such privation, “anything looked good to us, and the world started to make fun.”

Since that time, Russians rich and poor (the average per capita wage is a fraction of the cost of a Ricky bag) have become willing conscripts in the global consumer fantasy of arrival. Or so one might think from the hushed and Gatsbyesque mood so assiduously cultivated in Lauren’s new Moscow store.

“For years now, the Lauren brand was known, very well accepted and desired by Russians,” Verber said from her car phone en route to the south of France. “The reason is simple. People want things that look like they’re worth the money. They want this look of quality.”

What they want, of course, is their piece of the bewitching illusion that generations of revolutionaries and social reformers struggled (and died) to debunk. Somewhere in “The Worst Intentions,” the hilarious send-up of contemporary consumerism and class mania, Alessandro Piperno’s protagonist asserts that “today we can say with absolute assurance that Karl Marx with his mania for predicting the future was grossly mistaken.” I had Piperno’s book with me in Moscow. And it struck me — as I ambled by the immense shiny Vuitton and Dior stores on Red Square and the sad Lenin impersonator charging $2 to pose for photographs and then on to the cobbled lane, where the Bentleys were parked bumper-to- bumper outside Ralph Lauren’s store — that this might be the understatement of all time.

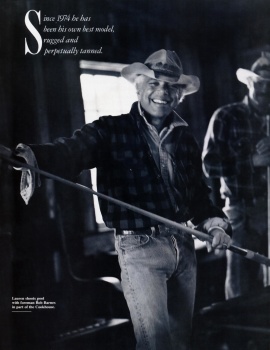

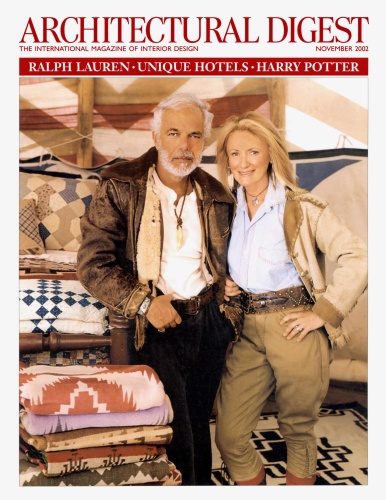

Kurt Markus

Ralph Lauren

Brilliant! D'accord.

Brilliant! D'accord.

, Ralph and co (Tommy Hilfiger, Michael Kors) didn't even cross her mind.

, Ralph and co (Tommy Hilfiger, Michael Kors) didn't even cross her mind.