You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,582

- Reaction score

- 20,774

Vitamine W

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 15, 2010

- Messages

- 2,957

- Reaction score

- 965

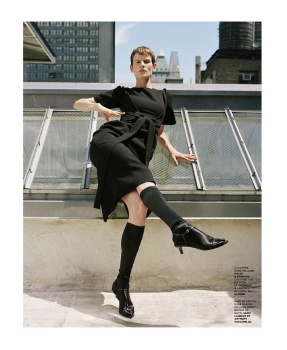

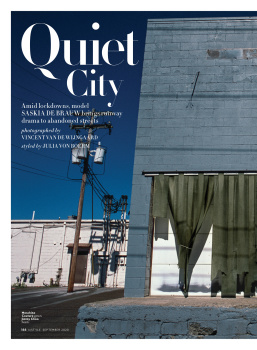

Saskia is the best poser in the game and has been for a while now. Convince me otherwise.

Nymphaea

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 30, 2012

- Messages

- 6,196

- Reaction score

- 695

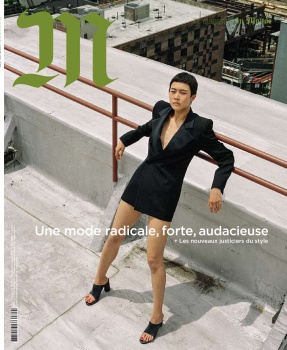

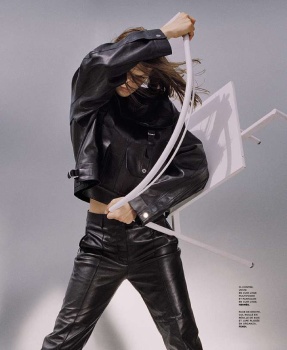

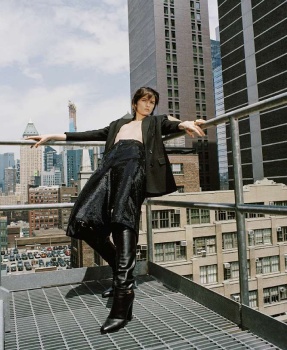

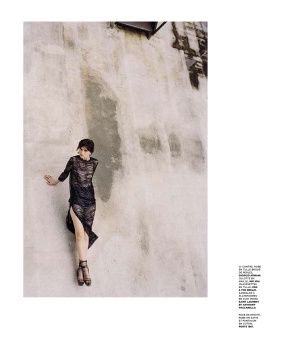

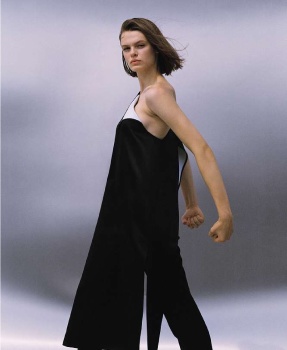

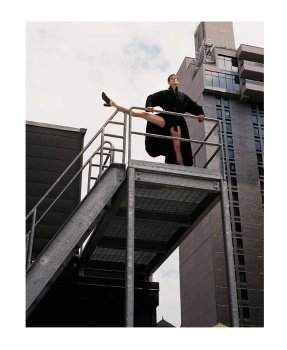

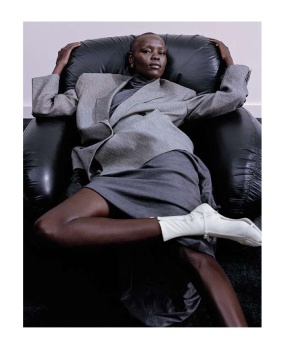

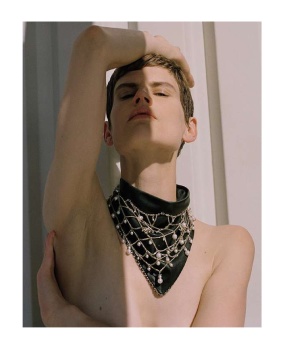

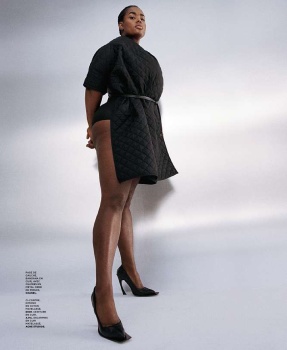

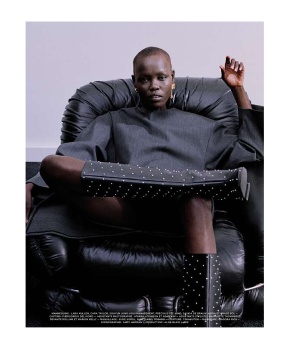

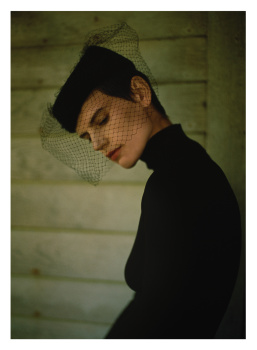

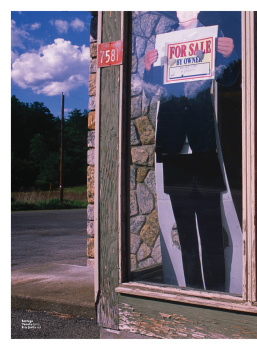

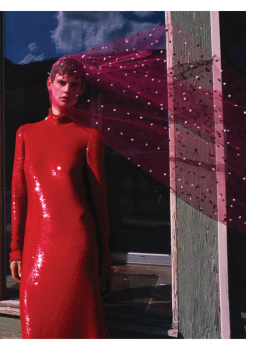

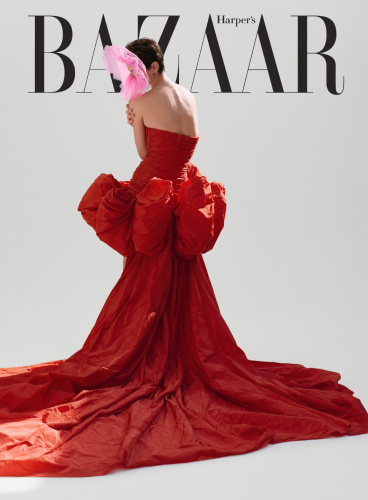

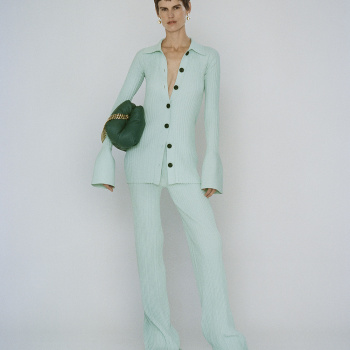

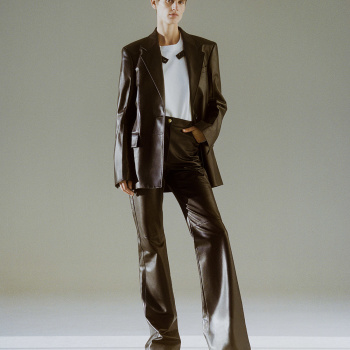

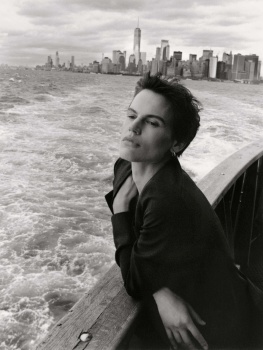

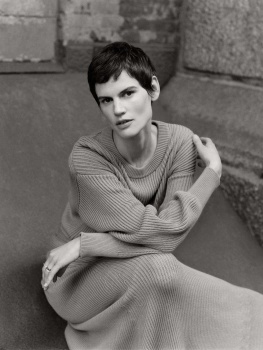

Porter by Net-A-Porter

December 6, 2019

Model Behavior

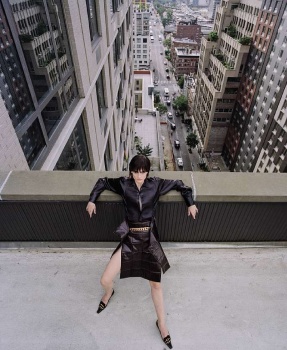

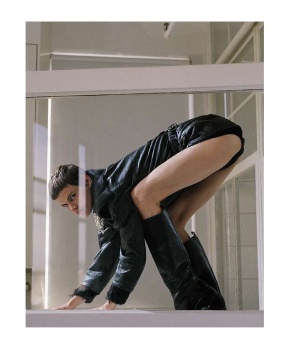

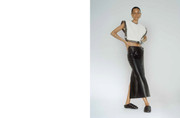

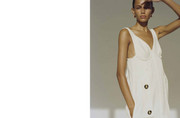

Model Saskia de Brauw

Photographer Quentin De Briey

Fashion editor Elissa Santisi

December 6, 2019

Model Behavior

Model Saskia de Brauw

Photographer Quentin De Briey

Fashion editor Elissa Santisi

net-a-porterShe’s a style icon who’s walked for almost every major fashion house, but Dutch model SASKIA DE BRAUW was a relative late comer to the industry she’s helped redefine with her androgynous beauty and refreshing honesty. JANE MULKERRINS meets the mesmerizing model who’s bringing cruise 2020’s key pieces to life…

It is a dank, drizzly day when the statuesque Saskia de Brauw greets me at the front door of the four-storey brownstone she rents in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. She and her boyfriend, the photographer Vincent van de Wijngaard, and their three-year-old daughter Luna relocated to New York from Paris three years ago. While de Brauw initially had reservations about the city and its speed, this neighborhood appealed to the Dutch native: “It’s beautiful, and you can have a garden here, but you have to travel to do your grocery shopping – there are no supermarkets in the neighborhood.” For most families, that would mean a car journey, but not de Brauw’s – they don’t even own a car. “We have a cargo bike for groceries,” she tells me; the two-wheeled vehicle with its large container is sitting outside the front door.

And though the nature of her work demands frequent flights, she’s conscious of that, too. “I have to offset a lot of travel,” she nods. “I use Cool Effect, but there are others – you fill out the hours that you fly and pay a little bit of money that goes to environmental projects like reforestation and providing villages in developing countries with LED lights.” She is making equally impressive environmental efforts at home. “I changed my shampoo for a simple block of soap shampoo, and when I go to set, I bring my own coffee cup, water container and cutlery.” That’s exemplary, I remark. “I think everyone has to do that,” shrugs de Brauw.

She leads me through the high-ceilinged, airy hallway into their cavernous open-plan kitchen-diner, where van de Wijngaard is working at his laptop. They met a decade ago, in her early days of serious modeling, when he shot her for a Dutch magazine. They didn’t begin dating for another couple of years – “it was a little complicated,” she demurs – but eventually moved to Paris together, where they spent seven years.

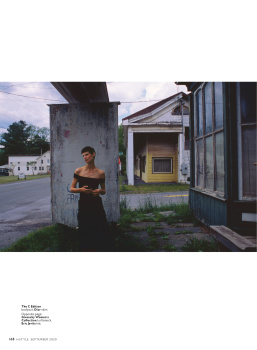

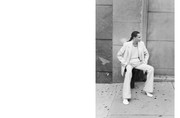

The couple has generally avoided working together, but last year a shared project came up quite organically. “I didn’t really enjoy coming here,” De Brauw confesses of her early days in New York City. “Because of its pace and the disconnect I felt. So, I started doing these slow walks through the city.” The walks, she says, didn’t have a destination, but the practice of aimlessly ambling through the city streets produced a soothing effect.

One day, she and van de Wijngaard turned her meditative jaunts into a film and series of photographs called Ghosts Don’t Walk In Straight Lines. He shot her as she walked the length of Manhattan, from 225th Street in the north of the island to Battery Park at its southern tip, wearing a full-length custom-made coat by her friend, designer Haider Ackermann.

The pictures were exhibited in London, Amsterdam and New York, and turned into an art book. Clearly, the 38-year-old model is far more than just a pretty face, albeit one whose angular, stone-hewn bone structure has graced the covers of magazines including French and Italian Vogue and featured in campaigns for the likes of Chanel, Prada, Saint Laurent and Armani. Over the course of her career, de Brauw has walked for almost every major fashion house, including The Row, Prada and Stella McCartney – and, while she no longer does the multi-city runway dash of Fashion Month, she recently reappeared on the runway for Haider Ackermann and Givenchy, and in couture shows for Fendi and Valentino Haute Couture.

All of which is the more impressive considering her unusually late entry into the industry at 28. Her age, she insists, didn’t make her early days in the business any less intense. “I think people felt, because I was older, that I was strong and tough, but I was actually very fragile and I needed a bit of help and guidance, which I didn’t know how to ask for,” she reflects. “You face a lot of disappointments and rejections and strange attitudes that you don’t always know how to deal with.” But, she says, one early agent offered up some valuable advice: “‘Les chiens aboient, la caravane passé’ [the dogs bark, but the caravan goes on]”. The dogs can be the people who are like, “Wow, you’re amazing,” and they can also be the people who say you’re not amazing – they can be all the noises from the outside world,” she says. “But you have to go on and not be bothered by the dogs.”

We settle back in the elegant lounge – de Brauw cross-legged on the floor – where tasteful, sparse but bohemian furniture is mixed with tiny red Adirondack chairs belonging to Luna, her childish drawings sitting alongside portraits by the likes of Russian-American painter Moses Soyer. “My boyfriend has an extremely good eye; he would find things all the time at the markets in Paris,” says de Brauw. She is far more self-effacing when it comes to her own art, however. “I don’t have a career as an artist,” she says, shaking her head. “I make projects when I have the desire to make them.” She spent years collating material for her first exhibition and book, The Accidental Fold, a collection of images of objects she would find on the street and scan into the portable scanner she carted around. “Small things that are often overlooked – those are the things that touch me very deeply.” She carries a notebook with her at all times.

It’s all a far cry from the self-promoting, look-at-me social media persona frequently demanded of models these days. “That’s a real struggle for me,” she nods, mentioning her particular disdain for “Instagram models doing yoga that’s not yoga. Yoga, for me, is a serious thing – it’s the union of the body and mind,” she says. She also disappeared off-grid on a meditation retreat to the Plum Village center in the Dordogne a few years ago, where she did walking meditations with the Vietnamese monastic and writer Thích Nhất Hạnh. “Experiencing his presence was very special,” she says, a little dreamily.

De Brauw grew up in the village of Baambrugge, 15 miles outside Amsterdam, where both her Dutch father and Glaswegian mother were lawyers. She had no interest in fashion growing up; “I still don’t really,” she laughs. “But I do like beautiful, well-made things,” she admits, when I compliment her on her elegant navy blue sweater and skirt. She was extremely interested in horses – “I groomed every horse in the village, but not chic horses – these were Shetland ponies. I was cleaning their scruffy fur and making them jump hurdles. I was always outside.”

She was discovered at the age of 16, on a tram in Amsterdam, and did some jobs for various Dutch brands and appeared in local runway shows. “But I also had an eating disorder and that probably wasn’t helpful. If you do a job that’s so related to your body, it’s better to feel reasonably happy with where you are or who you are.” By that point, she says, “I had this drive in me to perform really well, so I had super-high grades, but I did my final school exams without eating. I wasn’t menstruating anymore. I was miserable inside.” Her parents, she says, told her: “We’re going to solve it.” And, eventually, through therapy and healing, they did. “It really took a couple of years to find that healthy relationship with food again. But now, I’ve been free from it for so many years. It’s not something that’s lurking around the corner, it’s just not there in my life anymore. For people who are going through it, that’s hopefully nice to know – that it really is not something that has to stay with you all your life.”

Meanwhile, she enrolled at university, initially believing she’d follow her parents into law. “But the subject that I loved the most was philosophy of law, so I only did one year.” She switched to history of art, but also found that too dry. “It was very academic and I was just sitting there, thinking, ‘I didn’t sign up for this.’ Of course, I just wasn’t ready for it.” She ended up studying photography and textile design at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie. Modeling only came up again, at the suggestion of a friend, as a way to make ends meet. “Most agencies were, like: ‘No, it’s not your time. That’s the past. Do something else,’” she recalls. One agency, however, was willing to give her a shot. Her first booking was a Balenciaga show. “I had no clue that it was a big deal,” she laughs.

For much of her early career, designers and casting agents played heavily on de Brauw’s angular androgyny. “I’ve had short hair all my life and, when I went to high school, I was always called a boy.” While living in Paris, she would frequently be called “monsieur” in the boulangerie. “Once, my uncle even thought I was my brother.” Do they look very similar, I ask? “My brother is about one meter taller than me,” she deadpans. I, too, have a pixie cut, not unlike de Brauw’s, and, I tell her, it’s commented on far more frequently in the US than in Europe. “Yes, I think hair is very important here,” she muses. “You have your hair done for the weekend, and you get your nails done. Who has time to get their nails done?” She stretches her long legs out as she ponders this. “In the Netherlands, there is a practicality to life. You’re on your bike, so some hairdos really won’t work, and you can’t wear a hat – it’s going to blow off your head. You’re not going to wear heels all the time, because that’s not practical on your bike either.” She chuckles softly. “It’s not very romantic, perhaps, but I think maybe the Dutch woman is just very practical.”

Alien Sex Friend

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 26, 2005

- Messages

- 8,596

- Reaction score

- 1,455

Alien Sex Friend

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 26, 2005

- Messages

- 8,596

- Reaction score

- 1,455

Alien Sex Friend

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 26, 2005

- Messages

- 8,596

- Reaction score

- 1,455

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)