You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

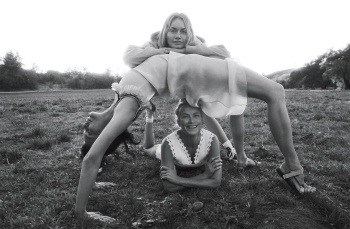

WSJ. Magazine May 2021 : Amber Valletta, Shalom Harlow & Carolyn Murphy by Lachlan Bailey

- Thread starter TZ001

- Start date

D

Deleted member 141309

Guest

This is all we need, 2021 is cured.

But I wish their faces were a teeny tiny bit more facing the camera! LOVE this.

But I wish their faces were a teeny tiny bit more facing the camera! LOVE this.

I just wish that Carolyn’s wasn’t sticking her tongue out and was smiling only. THEN it would’ve been perfect. it bothers me a little, but I’ll take it.

This is exactly how I feel.

mikel

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 30, 2005

- Messages

- 26,704

- Reaction score

- 5,813

Here is the accompanying article:

wsj.comAmber, Carolyn & Shalom: The Neverending Joy of ’90s Supermodels

Nineties fashion icons Shalom Harlow, Carolyn Murphy and Amber Valletta, now in their 40s, are passing wisdom on to a new generation of models—and continuing to dazzle in their own right.

By Elisa Lipsky-Karasz

One night in Paris in the early ’90s, two teenage girls, one brunette and one blond, perched at an outdoor table at a restaurant in the Marais. It was straight out of a Godard film, with a nearby ballet school whose rehearsals they could glimpse in the mirrors. They swapped stories about their hometowns, where they grew up with strong-willed single moms: places with flat-voweled names—Oshawa, Ontario, and Tulsa, Oklahoma—that rhymed somehow with their own names, Shalom Harlow and Amber Valletta. They discovered a shared love of the author Tom Robbins, whose work includes the 1976 book Even Cowgirls Get the Blues. Its big-thumbed protagonist, Sissy Hankshaw, was looking to get out, something the girls knew a thing or two about. That restlessness had brought them to Paris, and now it had brought them here, to see if they could pair up to escape their modeling accommodations.

By the end of the night, they decided to live together: their first grown-up apartment, even though they were barely grown-up.

Around the same time, a teenager whose family lived in the Florida Panhandle—that part that’s more like the coast of Alabama—was at a finishing school, sent by her Virginian mother in an effort to coax out her daughter’s refined side. Carolyn—never Caroline—Murphy couldn’t see the point of walking with a book on her head and keeping a binder of potential hairstyles, but there was one area where pupils got some freedom: the self-styled runway session at the finale of the eight-week program. A rebel with a Grace Kelly face, Murphy chose vintage Levi’s and a men’s Hanes V-neck T-shirt for her first look, with bare feet and a piece of turquoise jewelry. Already a chameleon in training, she next picked a classic black dress with red lipstick, straight out of a Robert Palmer video. To everyone’s shock, modeling agents soon came calling, though she heard “too pretty” many times: agent code meaning she was suitable only for commercial work, not for the rarefied world of high fashion. After finally making it to Paris in 1991, she found that Harlow and Valletta already had the town seemingly sewn up.

“We just had a good stereo system and a bong,” says Harlow, 47.

“I’m sitting there like this little kid just out of Virginia and Florida, going, Oh, my God, what the f— am I doing here?” recalls Murphy, 47.

But within a matter of years, these three had discreetly dislodged the single-named supermodels who came before. Without the big hair and big attitudes, Harlow, Valletta and Murphy were everywhere, whether it was the cover of American Vogue, the groundbreaking Marc Jacobs “grunge” collection for Perry Ellis in 1993, the 1995 Gucci collection that made Tom Ford’s name, MTV’s House of Style, that time in 1998 when Alexander McQueen had robots spray-paint a dress live on the runway, the moment pre-millennium when Donatella Versace took on her late brother Gianni’s legacy with the navel-baring “jungle” dress—at least one of them was there.

And now, nearly 30 years later, they are still here, three answers to the question, “How do you survive, even thrive, in an ever-evolving industry that’s famous for eating its young?”

“They are one amazing iconic triplet—they are the late-’90s alt-queen supermodels,” says designer Jeremy Scott, who shaped his recent fall 2021 Moschino show around a vision of Harlow as Rosalind Russell in the 1939 film The Women, and cast all three for his cinematic presentation. “I said on set to the other models, ‘We are on the set with [legends], let’s pay homage and respect…. These are the ladies whose careers you hope to have one day.’ ”

According to two industry sources, this triumvirate can still command paydays at the top of the scale, on par with decades-younger stars like Gigi and Bella Hadid—forget Linda Evangelista’s legendary $10,000.

“I never wanted to see [the original supermodels] out of work for us to take over,” says Valletta, 47. No, they wanted to study Linda, Christy and Cindy and all the other “supers” who were then on magazine covers monthly. And study they did, at shows, cheering like hooligans at the backstage monitors, says Harlow, and at group sessions with legendary photographer Steven Meisel. “Steven’s responsible for a lot of that lineage being carried through to us,” says Harlow.

In return, they have defined decades of beauty. Their rise during the ’90s was in concert with mega-fashion’s deflation—their slim physiques and unpretentious personas meshed with both the reality-inspired grunge looks and the sleek, uber-minimalist styles they modeled. Not everyone was a fan: One fashion critic dubbed them, along with their British compatriot Kate Moss, the “anti-models,” although even back then Harlow was as classically elegant as Richard Avedon’s longtime muse Dovima. Valletta reminded photographers of a Hitchcock heroine, and though Murphy chopped her hair short and dyed it alternately platinum and black, she couldn’t escape comparisons to ingenues like Romy Schneider. Along with a new generation of fashion photographers, they helped usher in an era of naturalism that still influences the industry today.

“They broke the supermodel mold,” says James Scully, a longtime casting director, who has worked with Tom Ford and Stella McCartney. “They were considered unconventional at the time.”

One early image of Murphy shows her making a squinched-up naughty face, like a 3-year-old imp caught drawing on the walls, while Harlow and Valletta, who as roommates were often booked together, appeared early on in W magazine sitting on plastic lawn chairs in the middle of a field, wearing the velvet hip-huggers they had recently modeled for Tom Ford’s game-changing collection.

For Vogue’s September 1995 cover, photographed by Meisel, the pair swapped those lawn chairs for a decorative park bench and the pants for ball gowns. Even so, that fresh feeling still breezed around them. By the 1997 VogueMarch cover, again shot by Meisel, again on a bench, this time with sleek cream dresses, their identities had somewhat cemented: Valletta’s cool, geometric gaze and avant-garde posing angles; Harlow’s Ava Gardner eyes, dancer’s grace and Mona Lisa smile. The next month, Murphy joined them for the Vogue cover, barefoot on the beach in floral gowns. She had begun morphing from a surfer chick into the epitome of American chic. She was always working overtime to make up for being shy and what she calls “super tiny”—5 feet 8½ inches.

“I remember that [April 1997] cover, like, What am I doing here?” says Murphy, who was dubbed “Mamma Murphy” for her sensible side. “I have photos of every hotel room,” she says. “I remember when I had my first fancy hotel room, the first time I flew first class, the first time I went to the party.” Despite being the oldest of the trio by several months, she says she looked up to Harlow and Valletta as she found her footing in the industry.

As for the two roommates, Valletta says, “We competed with each other for sure.”

That competition is “a complex thing to navigate in any relationship,” says Harlow, the designated “deep thinker” of the group, as they call her. “The essence of who we are is commodified—you know, there will be one job, and maybe the three of us are up for the same job. And really it comes down to things you can’t control—it’s not like one of us can rehearse better or hone our skills. Sometimes it’s just filling a box with a blonde or a brunette or whatever.”

Valletta calls Harlow the “yin to my yang.” They shot together so many times that eventually they got fed up with it, like a band that has had to perform the same hit too many times. “It got to a point where it was like, wait, we are individuals, too,” says Harlow. Nonetheless, she and Valletta value their sisterly bond. “It’s given me a place to look deeper and see how I want to cultivate a friendship and have to own things that maybe I didn’t want to look at. It’s complex, but it’s nurturing,” says Valletta. “You come up against yourself—we challenge each other that way.” Now they are the equivalent of blue-chip artists, lending validation and gravitas to campaigns they appear in and showing the younger models how it’s done. “I think they just think, Who’s that old lady backstage with us? Why is she here?” says Valletta with a laugh, of models who are often younger than her college-age son. She and Murphy have grown close over their single motherhood: Both have kids in their early 20s, Murphy a daughter named Dylan and Valletta a son named Auden.

Dylan loves the ’90s fashion that her mother has kept, including pieces Murphy bought on one post-shoot spree in 1998 in Paris with Meisel. “Steven was very much like, We’re [finished]—we’re going shopping!” Murphy recalls. “And [then] we’re piling into a Mercedes. Next thing I know, we had gone to Louis Vuitton, and I was given things—a coat and bags—and then we went to Prada, where I bought a few things.” She still has those, though she says she herself is not a clotheshorse. “I’m saving a lot of pieces for [my daughter]. I also think they’re art pieces unto themselves…like this gorgeous blush-pink dress that Narciso Rodriguez made for me.

“The fashion industry is quite small in some ways,” Murphy adds. “If you think about it, we all grew up together—we’ve been through so much and spent so much time together. That familiarity is quite comforting. Once I realized that, it was a turning point.”

Today’s shift away from the familial aspect of fashion and toward digitization and social media is something they feel collectively ambivalent about. “We still had the real raw deal,” says Harlow. “And now, it’s not like the ‘house of whatever [designer]’ anymore, it’s traded on the stock market, and that’s really apparent.” As for social media, says Harlow, “there are the algorithms [and] the pace of it, and it’s kind of feeding an evil machine in the sense that there is no mystery left. You post immediately after you’ve done a shoot.”

It used to be just “the photographer, the stylist and maybe an assistant,” says Valletta. “Now I don’t even know what all these people are doing [on set].”

“The flow is constantly interrupted because everyone’s looking at the monitor…or their phone,” says Harlow. “Even just the pop and flash and the sound of the camera, there was a rhythm to that.

“It’s [our job] to have this character, to have some study behind it and have references,” says Murphy. “I remember some photographers bringing books.”

This training and expertise has been part of their staying power. In 2001, Murphy signed a contract with cosmetics and skin-care company Estée Lauder that’s still going, 20 years later. Valletta has gone from working with the late designer Yves Saint Laurent to modeling for the international juggernaut that still bears his name. Since taking college classes on environmental studies in the late ’90s, she has made sustainability a serious focus, including collaborating with the Sierra Club on a 2018 documentary about clean energy. Meanwhile, Harlow was a longtime favorite of Chanel’s late designer Karl Lagerfeld. After a multiyear absence from campaigns, she made a return in 2018, closing the Versace spring 2019 show, followed by an ad centered on a dancing shoot with Meisel, a video of which went viral on Instagram, complete with some fans mimicking her stomping, joyous moves.

“These women can go into any designer and be anything they want them to be,” says Scully. “We keep going back to them because they have everything.”

The three keep in touch by group text, especially over the past year, when they all found themselves on the West Coast during Covid-induced stay-at-home orders: Murphy, who is bicoastal, joined her family in Los Angeles, where Valletta lives full time, and Harlow, who recently relocated from British Columbia, is in Southern California, studying somatic healing modalities. She recently launched her own private practice.

Each has suffered challenges: Valletta got sober when she was 25 and has spoken openly about her life in recovery from addiction, while Murphy has raised her daughter on her own. Harlow has suffered years long chronic illnesses and immune dysregulation brought on by a parasite contracted during an overseas shoot in combination with Lyme disease and prolonged exposure to black mold in a house she lived in. Her condition became so severe that she experienced seizures, and her body was so depleted that she found herself unable to walk very much at all, she says. Then, “there was this day where I could feel a little bit of the bounce come in. I wrote about it. I sang about it. I was like, the bounce is coming back,” she says with a grin. All three of their mothers have suffered from breast cancer, to which Harlow’s mother succumbed this past year. The three women gathered recently in Los Angeles to grieve Harlow’s mother, as well as their friend the model Stella Tennant, who died suddenly in December, days after turning 50.

They each posted photos from that day on their Instagrams, the three of them alone in the woods, no photographers, no makeup artists, no stylists. Just some ladies out for a hike wearing jeans and sneakers. “We cried a lot,” says Harlow. “We talked about Stella, we also talked about some of our own stuff within the business that we’ve been going through in the last few years, and Shalom having just lost her mama,” says Murphy.

“And then the laughter, the joy came—there’s a safety there and for us, we’re just where we are at in our lives as women,” says Harlow. “This is lifelong good stuff,” adds Valletta. The photos resonated throughout the industry, garnering nearly 20,000 likes on Valletta’s Instagram feed, for one, with everyone from Michelle Pfeiffer to Liv Tyler commenting.In Old Hollywood style, the three won’t share the secrets to their preternatural appearance. “We have the holy grail,” says Murphy, with a laugh. “We swore on it in 1996.”

As for the pandemic, “This has been a collective pause,” says Harlow, ever the philosopher. “So what rises to the surface is…true love, true friendship to support, contact, relationship, community. And I think the gift is that we are coming out of this with all of this intact.

bluestar

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 18, 2013

- Messages

- 2,398

- Reaction score

- 477

UGH I am in love!!! I remember seeing their cute reunion on Instagram awhile ago where they were acting silly and playful and I was living for it. Now seeing this version for WSJ made my day! The cover + photos all give off genuine happiness, which is something you don't see in many magazines anymore.

Summer Day

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 8, 2020

- Messages

- 313

- Reaction score

- 346

I had flashbacks to their reunion on Instagram some months back as well. Guess this was the result.UGH I am in love!!! I remember seeing their cute reunion on Instagram awhile ago where they were acting silly and playful and I was living for it. Now seeing this version for WSJ made my day! The cover + photos all give off genuine happiness, which is something you don't see in many magazines anymore.

mikel

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 30, 2005

- Messages

- 26,704

- Reaction score

- 5,813

Their reunion on Instagram and this shoot were two separate occasions.I had flashbacks to their reunion on Instagram some months back as well. Guess this was the result.

Summer Day

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 8, 2020

- Messages

- 313

- Reaction score

- 346

Oh, had no idea. Thanks for clarifying.Their reunion on Instagram and this shoot were two separate occasions.

[Piece Of Me]

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 29, 2008

- Messages

- 2,770

- Reaction score

- 703

This is just glorious! Wsj rarely disappoints and seeing these three icons together is an absolute joy.

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 50,024

- Reaction score

- 8,416

Beautiful cover story, i really enjoy see the supermodels on evey new editorial or cover.

D

Deleted member 141309

Guest

Oh My God! Corona? Cured. Fashion? Restored. Borders? Opened. Me? Deceased.

Every photographer, every model, every editor, every art director, if any of you ever read this comment - this is how it is f**king done.

Every photographer, every model, every editor, every art director, if any of you ever read this comment - this is how it is f**king done.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 39

- Views

- 24K

- Replies

- 32

- Views

- 21K

- Replies

- 22

- Views

- 6K

- Replies

- 37

- Views

- 19K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)

New Posts

-

-

-

-

Dolce & Gabbana Holiday 2024 : Awar, Felice, Lulu, Kit & Mathieu by Gordon von Steiner (4 Viewers)

- Latest: FashionPower

-