Costuming and Cinematic Language: A Conversation with Edith Head

EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION | What do we recall from a movie long after we've seen it? Unless we're rabid students of cinema, most of us soon forget the astute directing, the crisp editing, the crackling dialogue, even the memorable acting. What we're likely to retain years afterward is an image of a particular moment--Cary Grant impeccably framed in a doorway, Mae West in erotic locomotion across a room, Audrey Hepburn angelically poised or Paul Newman brimming with warmth.

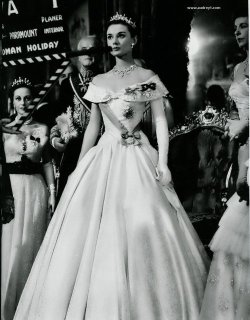

For more than 50 years, the entire modern period of movies, the redoubtable Edith Head (1897 - 1981) saw to it that we retained those images. Head (right) is the doyenne of Hollywood costume designers: she has worked on more than a thousand films, everything from She Done Him Wrong (1933) to The Big Fix (1978), and she has dressed almost every significant screen star.

Head outlined the medium of clothes to AFI Fellows during a seminar on November 23, 1977.

On the role of the costume designer

What we do is a cross between magic and camouflage. We ask the public to believe that every time they see an actress or an actor that they are a different person.

We have three magicians: hair, make-up and clothes. Through those, we're supposed to kid the great public that it really isn't Robert Redford at all, he's Butch Cassidy or he's in The Sting (1973), or he's somebody else.

It doesn't matter so much with men, but with women we are able to do actually magical things, particularly in period films: changing their figure, making them over. But I think the important and interesting thing is that we do have the power of translating through the medium of clothes, and that's why I think we're a very important part of the whole cinema project.

I'd like to think that if the sound went off, you would still know a little about who the people were. There are two schools of thought. One school says, "It's all right to have the heroine look like a heroine, and the villain look like a villain," and then there's the other school, which says, "Let's fool the public. Let's have the heroine look like a dangerous woman."

So, when you work with a director or producer, you have to find out immediately what their point of view is. Do they want to tell the story visually, or do they want the people not to know who is the wicked person, or not.

The fundamental goal of clothing in a motion picture is translating the wearer into what they are not. That's the difference between clothing in pictures and clothing in real life. In real life, clothing is worn for protection or whatever reason you like. In motion pictures, it's to help the actress on the screen to give the impression that she is the person about whom you are telling in the story. In other words, we go through any kind of device we can to break the mold of the actress. If it's an actress who is known for wearing a certain kind of clothes, we usually go to an extreme to break the concept. We try to almost shock the public into saying, "Well, I don't believe that's Grace Kelly after all."

On the process

You read the script and then you break it down to a very concise "wardrobe plot" in which every actor and every actress and every part is defined--it's quite a document. You take that and have your preliminary meeting with the director and producer.

You've seen something by Alfred Hitchcock, George Roy Hill and Joseph L. Mankiewicz--well, all three of them are completely different. Now, with Hitchcock, he'll send you a script and you say, "Hitch, what do you like?"

He'll say, "My dear Edith, just read the script." That's it. So until you have sketches ready to show him, you don't go over that with him.

George Roy Hill, on the other hand, when we did The Sting and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), had done as much research as I had done. In fact, he had done more than I had on some of it. He is an absolute, super perfectionist. He had every book of research I had; he knew what an aviator wore in The Great Waldo Pepper (1975). He knew things of that sort. So when you work with him day by day, you work as though he were another designer.

I never met Mankiewicz because it was another studio and they borrowed me just to do clothes for Bette Davis. He called me and he said, "I love your work, just do what you think is right." So you see, that's three different languages. You can get directors who are charming, you can get directors who are completely uncooperative.

On the relationship between the costume designer and production designer

The production designer is, to me, the individual to whom I show the sketches before I even show them to the director. I think that unless you synchronize the fact that the room is a cool color or a hot color, or it's going to have a floral pattern or no pattern at all, it's impossible to do a coherent job of designing.

I not only work with the art director, but also with the set decorator, because I know that people have been caught doing a blue nightgown in a blue room in a blue bed with blue pillows.

Also, I work with the cinematographer. It isn't as bad now, but before color we did have a great problem, because there were certain things they wouldn't shoot. You couldn't shoot dead white--some of them wouldn't--and certain colors they just didn't handle. But I've discovered it's much safer to ask anybody with whom you are working on the whole team, so at least when you present your sketches you know that there's not going to be trouble later.

The ideal contribution of a costume designer

I think that wise producers and directors feel that we can give an added security to the actors and actresses by the way they are dressed. Don't forget that the average actor goes in front of the camera not portraying himself, but portraying somebody with whom he may not have any great rapport, and so if we can physically translate them into the part, I feel we can give security, which is crucial.

Through the medium of clothes, particularly necklines for close-ups, that's where you can do a great deal to help directors and producers. I even work with writers. A lot of times, you're working with a writer and he describes a costume or wants to know what will help motivate the story.

As you break down and make your costume plot, you make a little side note: ask the director if he thinks that if she wore a hat with a veil in this scene it would help the mystery, or little things that you might think of yourself.

On using sketches

When I go to see a director, I take a sketch pad and a pencil, which I stick in my hair, and as he talks, I sketch. That's why I think people should know how to draw a little. I'll say, "Do you like this sort of thing with a turtleneck sweater?"

He'll say, "No, I see it with a low neck and a scarf," so I quickly do that.

This is all so I won't waste time shopping because I already know what he wants. I've discovered it's much better to communicate with the eye than with the ear. Most directors and producers, and even actors and actresses, like to see something drawn, even if it's just a small pencil sketch.

I agree with you on the beauty of the costumes in The Birds, they're really phenomenal. Tippi Hedren's wardrobe in that film is a testament to classic elegance.

I agree with you on the beauty of the costumes in The Birds, they're really phenomenal. Tippi Hedren's wardrobe in that film is a testament to classic elegance.

I agree with you on the beauty of the costumes in The Birds, they're really phenomenal. Tippi Hedren's wardrobe in that film is a testament to classic elegance.

I agree with you on the beauty of the costumes in The Birds, they're really phenomenal. Tippi Hedren's wardrobe in that film is a testament to classic elegance.