You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Dries Van Noten - Designer

- Thread starter kit

- Start date

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,613

- Reaction score

- 1,353

gius

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 8, 2006

- Messages

- 10,853

- Reaction score

- 12

Thanks so much for posting that^ :-P I've been wanting to see this famous garden for some time. Sounds like a dream place I'm very curious about the jam. I was actually just thinking that spring '11 collection they really were "colours he didn't like".. Not so much the colour but the pairings --and they are all sort of growing on me

I'm very curious about the jam. I was actually just thinking that spring '11 collection they really were "colours he didn't like".. Not so much the colour but the pairings --and they are all sort of growing on me

I'm very curious about the jam. I was actually just thinking that spring '11 collection they really were "colours he didn't like".. Not so much the colour but the pairings --and they are all sort of growing on me

I'm very curious about the jam. I was actually just thinking that spring '11 collection they really were "colours he didn't like".. Not so much the colour but the pairings --and they are all sort of growing on meMulletProof

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 18, 2004

- Messages

- 28,937

- Reaction score

- 8,086

Ahhh.. what a incredible feature, so descriptive and comprehensive of his ideas on gardening.. I didn't know about this [the garden], but I think this somehow explains the sensible and accurate understanding of nature always present in his designs and presentations, and what he mentions at the end, the creativity triggered by the journey one gets into when entering a garden.

Ugh this makes me want to hurry up with my own garden..

By the way, this quote made me laugh for some reason ..

..

Ugh this makes me want to hurry up with my own garden..

By the way, this quote made me laugh for some reason

..

..Thanks for the lovely scans as always, MMA!!.. he has created an impressive secondary kitchen in the basement of the house where he pickles and makes what must be the ultimate designer jellies.

Last edited by a moderator:

sigh how i miss the old dries... imo, he really 'lost' it right around the turn of the century... i miss his early 90s mens... everything was sooo 'authentic' with its own unique edge... i still have one of his waistcoats from way back when everything was will 'made in belgium' in belgian linen and embroidered back...

^

same with me.i love dries collections from the 90ies to around 2004 very much. since then I find it nice, however does not speak as much to me as before.

by the way, is saw, that in the new volume of popeye magazine is an interview with dries.

same with me.i love dries collections from the 90ies to around 2004 very much. since then I find it nice, however does not speak as much to me as before.

by the way, is saw, that in the new volume of popeye magazine is an interview with dries.

Last edited by a moderator:

EnVogueLove

Active Member

- Joined

- Mar 1, 2010

- Messages

- 7,291

- Reaction score

- 4

So glad that we have this thread.

I would love to have this DVN book I will search throught the internet to see where I can find it. Anybody knows ?

I will search throught the internet to see where I can find it. Anybody knows ?

runner thank you so much for this thread.

I would love to have this DVN book

I will search throught the internet to see where I can find it. Anybody knows ?

I will search throught the internet to see where I can find it. Anybody knows ?runner thank you so much for this thread.

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 416

article from wsj.com

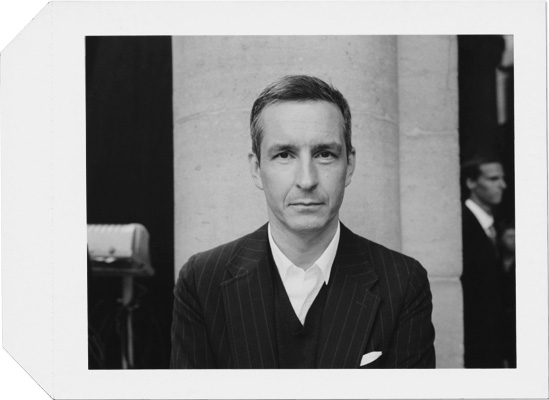

The Insider's Outsider

Dries Van Noten has built a booming business much to the envy of the fashion industry. How an idiosyncratic Belgian designer with particular notions about the way men and women should dress is quietly beating the big corporate conglomerates at their own game.

By DANA THOMAS

Portraits by Annabel Elston

HAPPY DAYS | Van Noten taking his daily walk with his beloved dog, Harry, along Antwerp's old port.

In today's fashion world of corporate ownership, design by committee and mass production and sales, Belgian designer Dries Van Noten is an anomaly. Since he launched his brand in 1985, the 53-year-old Van Noten has lived and worked in Antwerp, avoiding the fashion capitals circuit except for his shows in Paris.

He produces womenswear and menswear, and only twice a year—no pre-collections, no resort wear, no home wares, no jeans or perfumes or hotel decors. "Personally, I think there is too much fashion in the world," he says, sitting in his sparsely decorated office overlooking the city harbor on a cold autumn afternoon. "Now you can go on style.com or blogs and there is always another collection launch, cruise, resort, accessories, and on and on and that's a pity. For me it's an overdose."

Philippe Costes/WWD Archive

HAPPY DAYS | The Antwerp Six, the famed Belgian group of young designers in 1987. Van Noten is third from right.

Unlike a good many of his fellow designers, he is modest, soft-spoken and rather uncomfortable in the spotlight. He is not the sort to host trunk shows in big department stores, walk the red carpet or pal around with celebrities. He rises at 5 a.m. and works quietly and diligently, overseeing everything from design to the tissue paper that his clothing will be sold in. Van Noten spends his evenings dining at stylish local restaurants, such as Hofstraat 24—run by his friends, chef Roman Drowart and Laurence Van Bree—or at home. He shares a 19th-century manor with beautiful grounds outside of Antwerp with his business and life partner of 25 years, Patrick Vangheluwe, and their two-year-old Airedale, Harry. "It's a busy job, what we have here," Van Noten admits. "But we try to enjoy all three—fashion, house and garden—every day."

Van Noten is known simply for his clothes, and is loved for his clothes—a style that looks complicated and studied on the hanger but is, in fact, quite modern and easy to wear. Because of this, he has engendered a cultlike following: women who wear "Dries" (pronounced "drease," like please) are uniquely loyal to the brand. When you say you're wearing Dries to a fellow follower, it's almost like you are speaking in code about intelligent, artistic design.

Firstview

STRICTLY BUSINESS | Van Noten's 2004 runway show, celebrating his 50th collection, where editors and retailers dined on a table/runway

Unlike most major luxury brands, which often sell as much in accessories as they do in clothes, Van Noten's ready-to-wear accounts for more than 90 percent of his sales. He doesn't advertise, and he doesn't publish or reveal sales figures, but reportedly does an estimated $70 million in sales a year—a small amount compared to megacorporate brands such as Gucci, Prada and Hermès that rack up several billion dollars a year in sales. "I'm very happy with the size of the company as it is right now," he insists—blasphemy in today's $200 billion–a-year luxury fashion industry—adding boldly, "I don't have to grow."

Then again, and most importantly, Van Noten owns his company, an increasing rarity in luxury fashion today. In the last 20 years, most designer-run luxury brands have either listed on the stock market (like Ralph Lauren) or sold to corporate groups such as LVMH or Gucci Group or to private equity firms. Among the handful that remain independent are Giorgio Armani, Versace, Dolce & Gabbana, Oscar de la Renta and Sonia Rykiel.

The surge in growth in the last decade in luxury fashion has made it financially difficult for a young designer to launch a brand and for long-time independents to remain that way. "I've always worried that if I sold the company I'd lose my liberty, my freedom," says Van Noten in proper English punctuated with fluttering Flemish R's. "When you see what has happened to others who sold to groups, not everyone was very happy afterward."

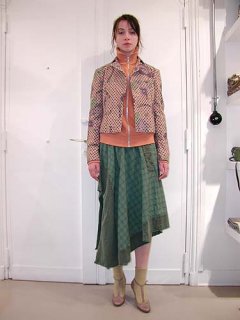

Firstview Three looks from the designer's spring 2012 collections

It's a way of running a business that luxury executives and MBAs consider downright old-fashioned. But remaining independent suits Van Noten and his lifestyle just fine. It allows him to keep an eye on just about everything that bears his name. He meets with many of his retailers personally in the showroom and explains the collection, which Marilyn Blaszka, co-owner of Blake in Chicago, notes, "is unusual." What's more, he listens to their opinions and takes them into account when designing the next collection. "I think he wants to know and is pleased to know how people wear the clothes," Blaszka says.

Though Van Noten does only four collections a year, he works incessantly, taking only four or five days of vacation a year. He adores Antwerp and is proud of the city. Anyone who comes for a visit receives a guide to the city that he put together of his favorite addresses. He often visits the Plantin-Moretus Museum in the old city center, with its burnished leather paneled rooms, romantic walled rose garden and collection of pre-1800 printing presses and books; he stops by Goossens, the tiny artisanal bakery on Korte Gasthuisstraat, for sugar bread, which he brings to the office; he trolls flea markets and antique shops to collect tin objects; he takes in art exhibits and particularly loves Francis Bacon, Russian Constructivists and the Flemish masters.

Julien Oppenheim

His men's store in Paris

"To go to exhibitions, to talk with people, to think, to research. That is the fantastic part of our job," he says. "For me, the most fun is the trip to create something that I really love. To do four women's collections a year? Forget it. You have two months, three months, click, click, click"—he snaps his fingers—"it has to be done, finished, next. Some designers make their show collection in two weeks. This, I don't like."

Instead, Van Noten focuses solely on spring/summer and fall/winter for men and for women and produces an astounding 1,200 designs for women and 800 for men—double the majority of his competitors. "I like to make a lot of clothes!" he says with a laugh. And, Blaszka reports, they sell "very, very well."

You can't have a business that loses money and money and money," Van Noten says. "When you have an investor, you can do that. But when it's your own money, you can't. I tried always to be very careful financially." He attributes this habit for fiscal responsibility to his upbringing.

Van Noten grew up in Antwerp, the youngest of four children of a clothing merchant and a stay-at-home mother. Van Noten's father had a fashion emporium 20 miles outside of town, "a destination store, which was a new concept back in the early 1970s," he explains. Throughout his teens, he spent weekends working in the store and during breaks from his Jesuit school he accompanied his parents on buying trips to Milan and Paris. It was understood that Van Noten would eventually run the store.

Courtesy Dries Van Noten

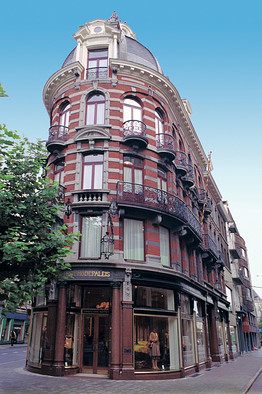

The Het Modepaleis store in Antwerp

When it came time for college, his parents gave him the choice: business school or fashion school. He found business "boring," and chose fashion, enrolling at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. A month into his studies, he recalls, "I told my father, 'I love designing so much I don't think I'm going to take over the company. I want to be a fashion designer.' And he became so angry. He said, 'If that is the case, you can study what you want, but I won't pay for it.' " Van Noten picked up freelance design gigs for an assortment of companies, including a children's wear brand and Donnay tennis, to pay his way through school.

At the Royal Academy, he met classmates Ann Demeulemeester and Dirk Bikkembergs. The students had ambition and used their connections to launch their careers. Van Noten had a men's jacket manufacturer and shirt manufacturer who were willing to produce clothes for him, so he designed a small menswear collection. "Dirk Bikkembergs had a contact of someone who made shoes, so he made men's shoes," Van Noten says. "And Ann Demeulemeester knew someone who made sunglasses, so the first thing she made was sunglasses." In 1986, together, along with Walter Van Beirendonck, Dirk Van Saene and Marina Yee, they pooled their money, put everything in a van, drove to London, rented a showroom space (which they divided into six) and presented their collections to retailers during fashion week. They were a hit and became known as the Antwerp Six.

Van Noten's first client was the famed retailer Barneys New York, his favorite store at the time. Van Noten was so nervous about the meeting, he says, "I ran away!" Christine Mathys, Van Noten's former boss at Donnay and his new business partner of sorts—no one really has a title at the company, he says—stepped in and handled the sale. Barneys bought Van Noten's menswear but sold it as womenswear.

In the early years of his business, "everything was hard, of course," he says. "But the hardest was the commercial and distribution side, to pick the right clients and to get your money. In the 1980s, you had a lot of stores you had to be in to be seen but didn't always pay. Susanne Bartsch, who had a store downtown, bought an enormous quantity of our second collection, of Harris tweeds in pinky pink. She accepted the first part and didn't pay, so we didn't deliver the second part. I can still see the racks of pink Harris tweeds hanging there." (When reached for comment, Bartsch said she couldn't recall.)

Ann Abelelston The designer walks along the water in Antwerp.

Last edited by a moderator:

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 416

part 2

In 1989, a prime retail property came up for sale in Antwerp: the Het Modepaleis, a five-story fashion emporium built in 1881 that sits on an acute corner, like the Flatiron building in New York. Van Noten renovated the place, overseeing every detail, from buffing the original bronze and mahogany fittings to the choice of curtain fabric. It's a habit he continues today: He decorates his stores himself, furnishing them with antiques and artwork that he and Vangheluwe find on eBay and at auctions. Looking back, he says, buying the Modepaleis "was one of the best things and the most stupid things I've ever done." Best because the space is a gem and solidified Van Noten as a serious fashion brand. Stupid, he says, because "it nearly killed the company [financially]. But we survived."

Two years later, close call No. 2 came: the Persian Gulf War. Most fashion companies lost a great deal sales-wise because American retailers slashed their spring/summer 1991 orders as the country went to war in January. Van Noten experienced that and more: "That season," he says, "I made the collection inspired by Iraq and Iran"—having conceived and designed it before Iraq invaded Kuwait. As it happens, he says, "we have a system where jacket names begin with a B for blazer, and skirts are with an S for skirt, so that season the blazers were called Baghdad, the skirts were called Saddam, and so on. All the shipments to New York were blocked in customs because the papers were filled with names of cities of Iraq and Saddam."

"That," he says quietly, "nearly caused us bankruptcy."

Jean Pierre Gabriel

STORE BOUGHT | A view of Van Noten's women's boutique in Paris

He recovered well enough that two years later he staged his first womenswear show in Paris, in the Hôtel George V's ballroom. He imported white mattresses and pillows from India and set them on the floor for editors and retailers to sit on. The models, wearing big flowery prints, walked the all-white room to Elvis Presley's "Love Me Tender." The reaction was so enthusiastic, Van Noten remembers, "it was scary." The result: "More clients."

That bubble lasted only so long. When the minimalism movement of Jil Sander, Helmut Lang and Miuccia Prada seized fashion in the late 1990s, Van Noten found himself struggling again. "We were doing a lot of rich prints, fancy things, as everything became more minimal and conceptual," he says. At the same time, corporate groups such as LVMH, Prada and the newly formed Gucci Group began buying up small, independent fashion companies like Van Noten's as well as major fashion suppliers. "Our shoe manufacturer group was bought by Armani, our heel manufacturer group was taken over by the Gucci Group and our last manufacturer was taken over by the Prada group," he explains. "Of course, when those people buy those companies, you are not the first served. We thought: Do we still have a future if we don't join a group?"

Eventually, he decided to talk to the big fashion groups, to listen to their pitch. He didn't like what he heard. "I made it quite clear that it was not so much my thing," he says. And that was that.

He felt the impact of his decision immediately. "We lost all our German clients in one season," he says. "They were told by the big groups, 'If you buy this line you must buy this other line—it's the whole package or nothing.' And our customers told us, 'Sorry, we don't have the budget for all of it,' and kicked us out."

Jean Pierre Gabriel A view of Van Noten's women's boutique in Paris

He soldiered onward, doing the clothes he wanted to do, selling them to the retailers he had long-standing relationships with, such as Barneys, Bergdorf Goodman and Blake, working with people he likes in a place he loves. A decade on, it has paid off. Today he has nine free-standing stores around the world, three of which, in Antwerp and Paris, he owns, 450 other points of sale and about 110 employees.

Remaining independent has allowed Van Noten to evolve at his own pace. Take, for instance, the fabrics he chooses for his collections, most of which are made exclusively for him up to a year in advance. This fall, he used a high-tech fabric from Japan that looks like tapestry. Two years ago, he had village women in remote Uzbekistan weave fabric that was carried by mule for a day and a half to the local DHL office to be shipped to his studio in Antwerp.

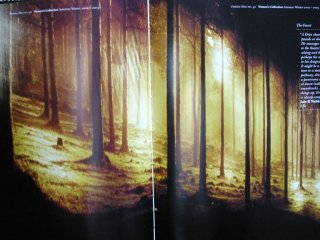

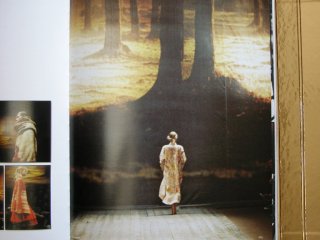

For his spring collection, Van Noten collaborated with a young British photographer, James Reeve, on a digital print of city skylines. Van Noten sliced up the printed cottons and silks and combined them with pieces of other printed fabrics he had made, of the jungle, the sea, 18th-century Italian landscape etchings and botanical drawings of roses, to create a sort of fabric collage in 1960s Balenciaga–like silhouettes. When he presented the collection during Paris Fashion Week in October, it was, as always, resolutely modern and feminine. Women's Wear Daily called it "mercifully calm."

They might as well have been describing Van Noten and his company. For 25 years, he's done exactly as he pleases, with all its ups and downs, and as he reflects on it, he remains as serene as his surroundings. "We all have our ideas and our dreams," he says as he gazes out his bay window at the pleasure yachts in the still port below. "It's important to have your dreams. But," he adds quietly, "I'm very realistic."

Last edited by a moderator:

HeatherAnne

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 24,230

- Reaction score

- 994

Fantastic profile on him softgrey, thanks for posting. It covered everything -- his background, history of the brand, and thoughts on everything beautifully and thoroughly, really enjoyed reading it and the pictures that accompanied it are lovely as well.  this man.

this man.

this man.

this man.its interesting how his clothing can be so embellished and yet so humble, much like the man himself. he defines the brand so clearly.

i hope his dad isnt still pissed at him.

aby...those pictures remind me of the paris visit. it still looks the same.

great post ms. softie.

i hope his dad isnt still pissed at him.

aby...those pictures remind me of the paris visit. it still looks the same.

great post ms. softie.

Last edited by a moderator:

it's funny his shop is right across the street from his family's generations-old department store....i think they're more than a little thrilled to see how far he's come. what i love about dries too is that he didn't use his family's reputation to gain his own success instead made his own and has become his own person in the city.

and you can't go anywhere in antwerp and not mention his name without everybody who knows him telling you what a kind,personable guy he is apart from he just being a talented designer. very down-to-earth.

it's funny when i was there,i was walking down the street making my way to kammenstraat and there he was walking the opposite side in the opposing direction with his partner patrick.

and the pictures....every time i see pictures of antwerp like that images regurgitate in my head.....i really miss it.

and you can't go anywhere in antwerp and not mention his name without everybody who knows him telling you what a kind,personable guy he is apart from he just being a talented designer. very down-to-earth.

it's funny when i was there,i was walking down the street making my way to kammenstraat and there he was walking the opposite side in the opposing direction with his partner patrick.

and the pictures....every time i see pictures of antwerp like that images regurgitate in my head.....i really miss it.

JuiceMajor

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 8, 2005

- Messages

- 4,509

- Reaction score

- 1

the house is beautiful!

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)