Erin O'Connor's article

I have three particular memories of childhood: a powdered substance called Build-up, which I drank twice daily in a pint of full-fat milk, Lyle’s Golden Syrup and cod-liver oil. My family were all deliciously rounded. I was not. I buzzed with energy, though – ballet, tap, swimming, athletics, cross-country running, all of which I loved and still do. But my mother’s mission in life, as ordered by our doctor, was to fatten me up. She failed. My growth spurts took place at breakneck speed – I have stretchmarks to prove it. I was agonisingly self-conscious about my height and the uncompromising angles of my lanky limbs. I grew upwards, never outwards (desperate to appear “normal”, I wore two padded bras), except for my nose, which appeared to have a life of its own.

In 1996, when I was 17, a friend and I went to the Clothes Show Live at the Birmingham NEC – a hot ticket, coveted by every teenage girl. I took a shift off from the old people’s home where I worked, in anticipation of picking up a bargain: I’d always been excited by fashion.

Inside, people began staring at me. It had been pouring with rain while we were queuing to get in. “My mascara’s run,” I thought. I bent over a bargain bin to hide my embarrassment. Then a woman began to circle me; it was like being stalked by a shark. Eventually, she said: “Has anyone ever told you that you are beautiful?”

My mouth fell open – I closed it hastily to hide my train-track braces. Nobody had ever said anything like that to me, except Mum and Dad, but what teenager listens to a word their parents say, especially about their appearance? I was used to being called “beanpole” or “Morticia”, because I hid my face behind curtains of waist-length hair. The boys reserved “stick insect” and “titless” especially for me.

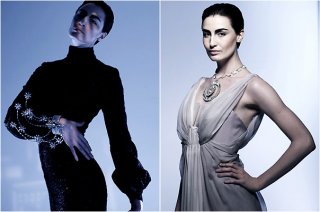

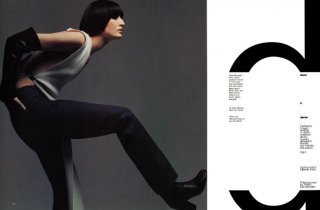

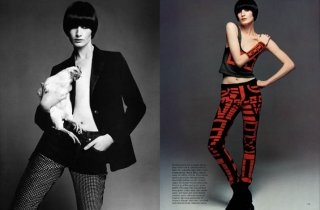

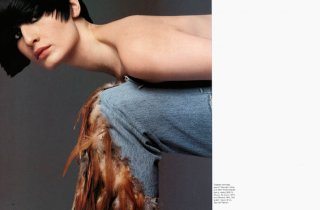

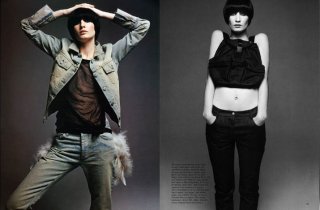

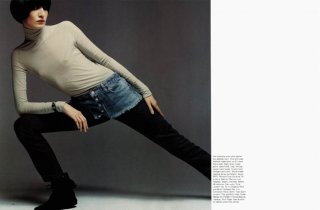

That woman, who has become a dear friend and mentor, turned out to be a scout from one of the world’s top model agencies. My parents were so proud, and so was I, although I wasn’t sure why until, at one of my first photo shoots, a hairdresser chopped off my security blanket with a large pair of shears. The revelation of my neck – yes! – gave me the first clue that my appearance challenged other people’s view of femininity. My imperfections added up to a look that encapsulated the exact opposite of the ideal of the supermodel then. For the first time, I was accepted despite being different, and even celebrated for it. It was an act of defiance on the industry’s part, and I, along with a few other models, represented a change. But my 11-year career as a model has not just depended on what I look like, but also on my ability to project character and personality, to interpret a designer’s creations so that they come to life.

That is why, a year ago, I was shocked when a few other models and I were singled out for criticism in the debate on BMI status – the size-zero furore. The public humiliation of seeing my health analysed by complete strangers – did I menstruate? Was I capable of becoming pregnant? Why was I skeletal? – was bearable. The questioning of my integrity was less so: we were made to feel as though we personally had set out to influence young kids into inflicting harm on themselves. Whatever the truth behind that accusation, it is a huge generalisation. A well-known writer even said she wouldn’t want her daughters to become the “empty-headed, self-obsessed, emaciated clones” she supposed models to be. It seems we are so dim-witted that we can’t even see when we’re being exploited. Recently, I was called “stupid” when I declined to answer a series of aggressive and offensive questions. In fact, I couldn’t: I was speechless.

After the size-zero storm had died down, the British Fashion Council launched an inquiry into models’ health. I was relieved that certain issues that sat uncomfortably with me would be aired and was eager to become a member of the panel. I have now had the opportunity to share my own experience with psychologists and doctors. For years, I’ve noticed a link between a model’s age and the prevailing body aesthetic: as the models get younger, the ideal frame has become smaller.

It seemed of the utmost importance to set a minimum age of 16, not only to protect the adolescents who are encouraged to model from as young as 13 (thereby promoting a spurious image of womanhood) but also to safeguard impressionable youngsters and even adult women from seeing these slight, adolescent bodies as role models. While I would never wish to interfere with any designer’s creative vision, we now have an opportunity and the responsibility to act on the panel’s recommendations to improve working conditions and adjust attitudes to models within and outside the industry.

For some time, I have tried to pass on to the new generation of models the benefit of my experience, which has been overwhelmingly positive. It’s not that I’ve escaped the hard knocks, but I’ve learnt from them and tried to keep in mind the reality of what works for me. I have set up workshops to inspire young models with a sense of self-worth and of their right to choose modelling as a career – which, it seems, many would now deny them.

As my confidence in what I was doing grew, so did my curiosity. I didn’t flourish at school, but over the past 10 years I’ve been making up for it. Modelling has given me a much broader view of the world, and the opportunities the industry has offered have enabled me to educate myself. Models often research and explore the historical figures and characters they have to interpret. Many people believe a model’s lifestyle to be given to freakish excess, but backstage you’d be hard pressed not to find a model with her nose buried in a book, or checking coursework. Modelling is a business that frequently leads its participants into other areas of work; many go on to finance their own companies.

British fashion is renowned for the dynamism and originality of its designers. Its models, too, are valued for their passion – we really love what we do. I’ve thrived on it all. With the current moves to regulate our industry, I hope that the many who come after me will enjoy and benefit from the rich experience it will offer them.

NEW BRIT GIRLS

AGYNESS DEYN

Erin’s heir apparent, Deyn, 21, from Lancashire, is the hot model of the moment. A scene girl who hits all the right parties with all the right friends, she has done catwalk and campaigns for Armani, Burberry, Chanel and more.

GEORGIA FROST

The rising star of 2007, Frost, 17,was also discovered at Clothes Show Live. She turned down a contract when she was 13 to finish school, but is on the cover of this month’s Harper’s Bazaar. The real one to watch.

GABRIELLA CALTHORPE

She may be posh – closely related to the Duke of Norfolk – but Calthorpe, 17, is transcending her Tatler roots to be embraced by the high-fashion crowd. Her struggle is to be more than a name – to be a face.

Erin O’Connor is a vice-chairman of London fashion week and a panel member of the Model Health Inquiry, which has been investigating health issues of models on the London catwalk

harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage.jpg29.1 KB · Views: 30

harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage.jpg29.1 KB · Views: 30 harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage2.jpg46 KB · Views: 38

harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage2.jpg46 KB · Views: 38 harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage3.jpg39.1 KB · Views: 29

harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage3.jpg39.1 KB · Views: 29 harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage4.jpg45.9 KB · Views: 31

harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage4.jpg45.9 KB · Views: 31 harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage5.jpg31.4 KB · Views: 28

harpersbazaar0299fashionmelainewardhairdidiermaligemakeupdickpage5.jpg31.4 KB · Views: 28