You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Irving Penn - Photographer

- Thread starter Estella*

- Start date

FashionTopFace

Member

- Joined

- Nov 8, 2007

- Messages

- 644

- Reaction score

- 2

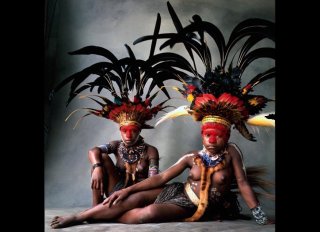

I'm grateful to find this thread. While I adore his fashion imagery, I think Penn's photographs of indigenous and working people are superior.

I Agree, Cuzco Children was his most expensive photograph about 500.000,- The way he portrays indigenous & working people is with high respect. Its also most touching that he in that position chooses to give a voice to those people. Those who are often neglected by society especially fashion and high culture society. I love that he is concerend with society and makes political comments, all greats were. My mom always said the bigger you become, the smaller you have to become. I love him so much it breaks my heart completely.

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,353

source | wwd.com

Irving Penn Dies at 92.

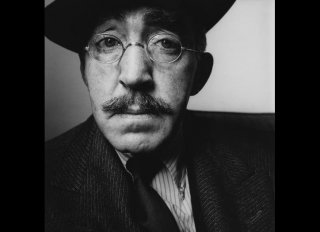

NEW YORK — Irving Penn, the master photographer whose fashion images in Vogue magazine for more than six decades bridged the gap between commercial photography and fine art, died Wednesday morning at his home in New York City. He was 92.

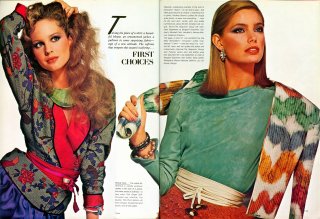

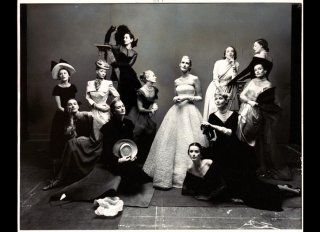

Beginning in 1943, Penn had a long career with Vogue, where he revolutionized the way fashion was presented to a mass audience. He shot more than 150 covers, more than any other single photographer, and was consistently showcased in the magazine’s pages.

“In my career, I have met no one else who worked with the level of imaginative intensity and economy of Irving Penn,” said Vogue editor in chief Anna Wintour. “His photographs were as exquisite and electrifying in the last year of his life as they were in 1943, when he started contributing to Vogue. To have been a colleague and friend of one of the greatest artists of the 20th century is a privilege greater than I could have ever imagined.”

Karl Lagerfeld told WWD his most treasured Penn print is a photo of his wife, Lisa Fonssagrives, in a look from the winter 1950 collection of Cristobal Balenciaga. “He was the kindest man on earth. His work was exquisite,” said Lagerfeld. “We used to spend hours chatting together. He used to speak about Paris in the Fifties.”

“His work in Vogue was not only focused on fashion — and I think that was very important for the magazine,” said Vince Aletti, photo critic and adjunct curator of the International Center of Photography. “He had a great vision and clearly loved his subjects. His shots were very reserved, spare, precise.”

Phyllis Posnick, Vogue’s executive fashion editor, first worked with Penn about 25 years ago as an assistant and then, later on, at Vogue. Posnick said while Penn did not like to be out in public and avoided being interviewed, he loved people and was always extremely accessible to other photographers. “More than any other photographer, he made us all go deeper and look beyond the obvious,” Posnick remarked. “He always kept digging and he always came up with something extraordinary.”

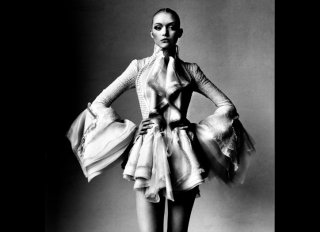

Penn and Richard Avedon were generally regarded as the two dominant fashion photographers of the mid-20th century, but their approaches were as different as their personalities. Avedon, who died in 2004, was almost as visible in front of the lens as behind it. His work, a longtime staple of Harper’s Bazaar, swirled with movement and vigor. Penn, shy to the point of reclusiveness, made pictures that were more cerebral. They reflected his early training as a painter. He related well to the architectural designs of Balenciaga and Issey Miyake.

“In [Penn’s] fashion shots,” wrote historian Colin McDowell in 2000, “it is the light in the spaces around the figures that gives it a unique quality. His fashion work was intimate but distant, a mixture of grandeur and emotion.”

George Chinsee, a WWD staff photographer and former retoucher and assistant to Penn, said the photographer was very strict in how he kept the studio during a shoot. “No one called him Irving — everyone called him Mr. Penn,” said Chinsee. “There was no talking or smoking, except for the conversation between his subject. Whenever someone came into the studio, he sat down and started talking to them. That conversation continued until the end of the shoot. It helped distract them.”

Leo Lerman, former editor in chief of Vanity Fair, wrote in his since-published diary on June 10, 1977 about being photographed by Penn, who also shot for the magazine. “It was intercourse on the highest level of being,” he wrote. “He nourishes, unlike Dick Avedon, who consumes. Irving brings out the finest in his subject. This was like a two-man meditation.”

Designer Bill Blass put it more succinctly when he told WWD in 1992: “The most influential fashion photographer in the last three decades is Irving Penn. No other photographer comes close to approaching him.”

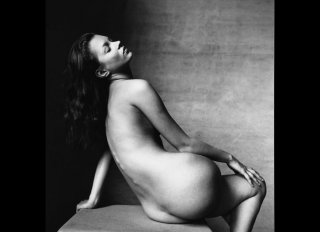

Penn was renowned for far more than fashion photography. His portraits of the Western world’s leading intellectuals, artists and writers — from Picasso to T.S. Eliot, from Colette to Cocteau — remain iconic, as do his pictures of lesser-known people — studio shots of Peruvian peasants, taken after completing a fashion assignment in Lima, and studies of workers in what he called the “small trades” — a New York City fireman, London charwomen, a Paris knife grinder — posing in his studio with their workaday tools.

One of his favorite subjects was his wife, a leading fashion model of the Forties and Fifties who appeared in some of Penn’s most widely reproduced pictures. They were married in 1950 and remained together until her death in 1992. Penn’s survivors include their son, Tom, a metal designer; a step-daughter, Mia Fonssagrives-Solow, a sculptor and jeweler; Penn’s younger brother, the director Arthur, and three grandchildren. His friend, Peter MacGill, said a memorial service will be announced at a later date.

In addition to his editorial work, Penn was equally admired for his advertising photography, especially on behalf of two longtime clients, Clinique and Issey Miyake.

Carol Phillips, who launched Clinique in 1968, came to the new Estée Lauder division from an editor’s position at Vogue and was thoroughly familiar with Penn’s work. His Clinique ads — characterized by clean, stark lines — were considered revolutionary because unlike campaigns for other skin care companies, they focused on the product and not on images of dewy fresh models.

Penn photographed Miyake’s fashion and fragrance ads for more than a decade. In 1999, in conjunction with a show of the Japanese designer’s work at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, Penn published “Irving Penn Regards the Work of Issey Miyake,” a 160-page book of photographs illuminating their long collaboration.

In the catalogue for that exhibition, Miyake said, “The clothes have been given a voice of their own!…Here were my clothes, but shown in such a way that they appeared totally new to me.”

Penn made art from even the most mundane objects. In 2004, the Philadelphia Museum of Art mounted an exhibit called “Underfoot.” It consisted of 30 black-and-white Penn prints of chewing gum that had been crushed into the sidewalks of New York.

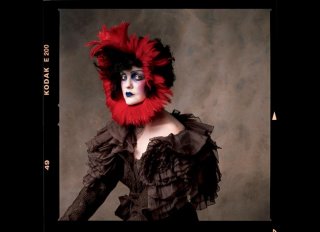

He was acclaimed not only for the pictures he made, but also for the process by which he made them. In 1964, unhappy with the way his pictures looked in the magazine, he began printing his new work and reprinting his older negatives in a difficult, expensive and esoteric process called platinum-palladium. It was a technique that had been used early in the 20th century by Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen. By printing multiple images of the same negative on fine paper that he prepared himself, Penn was able to achieve a startling degree of control over his images, to give them warmth and character and tone that slipped the bonds of commercialism to attain the status of art. He was one of the century’s master printers.

In June 2005, the National Gallery of Art in Washington opened an exhibit entitled “Irving Penn: Platinum Prints,” highlighting 70 photographs made from 1946 to the late Seventies, plus 12 collages Penn made in 1989.

Penn’s pictures, once available to collectors for a few hundred dollars, now fetch considerably more. Prints could cost up to six figures. In October 2004, a 1950 black-and-white photograph entitled “Harlequin Dress” brought $101,575 at an auction at Christie’s.

He was born in Plainfield, N.J., on June 16, 1917, but grew up in Philadelphia, where he attended public schools and dreamed of becoming a painter. When he was 18, he enrolled at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art, where he studied advertising design under Russian émigré Alexey Brodovitch, the celebrated art director of Harper’s Bazaar. While still a student, Penn worked as an office boy and apprentice artist at Harper’s Bazaar, sketching shoes and still planning on life before an easel.

He graduated in 1938 and was hired by Junior League Magazine as its art director. Later he designed ads for Saks Fifth Avenue. When he was 25, he took his savings and went to Mexico. Living on the edge of a volcanic wasteland, he painted for a year before deciding mediocrity would be the best he could hope for. He washed the paint from his canvases and kept them as table linens.

In 1943, he was back in New York, where he met Alex Liberman, another Russian expatriate and the man who would have a lasting influence on his life and career. Liberman, then art director of Vogue, hired Penn as his assistant. Despite the young man’s total inexperience as a photographer, Liberman asked him to suggest ideas for Vogue covers. Liberman admired Penn’s concepts and asked him to take some pictures himself.

Penn borrowed a camera and arranged a still life with a brown leather handbag, a beige scarf and gloves, a large topaz and a group of lemons and oranges. It became the October 1943 cover, and Penn was on his way.

Seven years later, Vogue sent Penn to Paris for the first time to shoot the fall couture collections. Penn did not take runway pictures. In search of a setting with natural light, he found space in a former photography school. It was a seventh-floor walk-up, and the windows were covered with dust. It was perfect. The dust diffused the light, giving the scene a romantic fragility that served to accentuate the bold lines of the Paris gowns.

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,353

source | wwd.com

The concept of contrast — in this case between the fashions and the setting — was pure Penn.

In his introduction to “Moments Preserved,” a 1960 book of Penn’s photographs and essays, Liberman wrote: “Penn, in his survey of life, has never lost sight of the coexistence of extremes. He has made systematic documentations of working men and their clothes. These, along with his fashion photographs and his portraits, are all part of the same grand plan of recording life, or the human comedy, at this one brief period of time.”

“I have always stood in awe of the camera,” Penn told the Independent of London in 2001. “I recognize it for the instrument it is, part Stradivarius, part scalpel.”

The apparel industry formally recognized Penn in 2004, when he was given the Eleanor Lambert Award by the Council of Fashion Designers of America as “one of the preeminent photographers of his time.”

In 1958, when he was named one of “The World’s 10 Greatest Photographers” by Popular Photography magazine, his statement of purpose dispensed with frills and was as pure and simple as some of his best images.

“I am a professional photographer,” he said, “because it is the best way I know to earn the money I require to take care of my wife and children.”

Attachments

-

irving-penn06.jpg49.5 KB · Views: 49

irving-penn06.jpg49.5 KB · Views: 49 -

irving-penn05.jpg26.2 KB · Views: 24

irving-penn05.jpg26.2 KB · Views: 24 -

irving-penn04.jpg28.8 KB · Views: 37

irving-penn04.jpg28.8 KB · Views: 37 -

irving-penn03.jpg40.3 KB · Views: 43

irving-penn03.jpg40.3 KB · Views: 43 -

irving-penn-01.jpg77.4 KB · Views: 19

irving-penn-01.jpg77.4 KB · Views: 19 -

irving-penn07.jpg78.5 KB · Views: 38

irving-penn07.jpg78.5 KB · Views: 38 -

irving-penn08.jpg42.6 KB · Views: 54

irving-penn08.jpg42.6 KB · Views: 54 -

irving-penn09.jpg55.8 KB · Views: 56

irving-penn09.jpg55.8 KB · Views: 56 -

irving-penn10.jpg47.3 KB · Views: 17

irving-penn10.jpg47.3 KB · Views: 17 -

irving-penn11.jpg79.6 KB · Views: 53

irving-penn11.jpg79.6 KB · Views: 53

fashionismydrug

Member

- Joined

- Jul 17, 2009

- Messages

- 607

- Reaction score

- 1

R.i.p

moussemaker

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 31, 2003

- Messages

- 3,149

- Reaction score

- 10

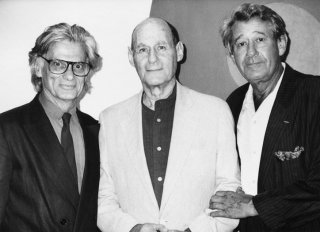

Newton, Avedon & Penn.

BerlinRocks

Active Member

- Joined

- Dec 19, 2005

- Messages

- 11,216

- Reaction score

- 15

^that is really the end of an era.

RIP dear Penn.

RIP dear Penn.

testinofan

███████████████

- Joined

- Aug 24, 2004

- Messages

- 7,407

- Reaction score

- 124

Sad news are igree Berin finish one fantastic era

Kurara_C

Member

- Joined

- Jun 11, 2009

- Messages

- 89

- Reaction score

- 16

In this magazine cover released by the Conde Nast Archive, the April 1, 1950 cover of "Vogue" with photography by Irving Penn, is shown. Penn, whose photographs revealed a taste for stark simplicity whether he was shooting celebrity portraits, fashion, still life or remote places of the world, died Wednesday, Oct. 7, 2009, at his Manhattan home. He was 92.

AP Photo/Irving Penn/Conde Nast Archive/Conde Nast Publications

BerlinRocks

Active Member

- Joined

- Dec 19, 2005

- Messages

- 11,216

- Reaction score

- 15

Those who are often neglected by society especially fashion and high culture society.

fashion ? certainly.

high culture ?

really not. have a look in a library.

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)

New Posts

-

-

-

The Music From Christian Dior Shows (PLEASE READ POST #1 FOR FULL SOUNDTRACK LISTS) (2 Viewers)

- Latest: evaislegit

-

-