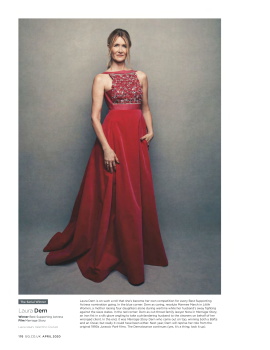

jexxica

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 14, 2009

- Messages

- 31,710

- Reaction score

- 372

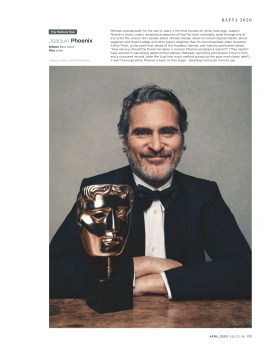

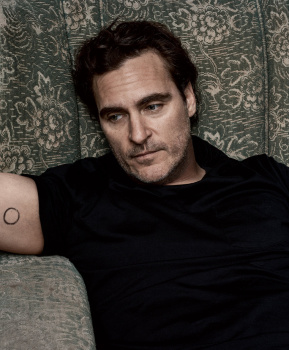

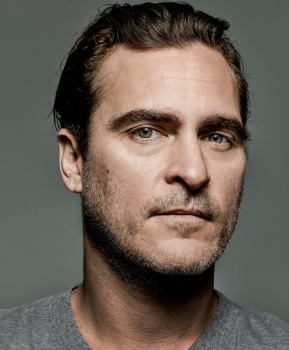

‘‘I’M 42!’’ JOAQUIN PHOENIX EXCLAIMS when asked why he has zero social-media presence. It’s a late afternoon in May — a few weeks before he wins Best Actor at Cannes for playing a contract killer in Lynne Ramsay’s ‘‘You Were Never Really Here’’ — and he’s sitting by an open window on the 11th floor of a high-rise overlooking the flatlands of West Hollywood. One hand clutches an iPhone-5, earbud wires are wrapped around his neck, a pack of American Spirits are balanced on his knee, his sunglasses are hung in the crook of a white tee. He has a dad bod and his stubble is grayish. Phoenix is an activist, primarily concerned with animal rights (he’s been a vegan since he was 3) and has supported, among others, PETA, Red Cross and Amnesty International — but how would anyone know this, since he has no social-media presence (no Facebook, no Instagram, no Twitter) to connect with followers and inspire them? It seems indicative of Phoenix himself; extremely passionate but unconcerned with the reality, the tangible facts, of what he does and who he is: the most soulful screen actor of his generation, and arguably its greatest.

His reticence to engage with Hollywood and the media is famous, and probably has its roots in how the press covered his older brother River’s overdose outside the Viper Room on Sunset Boulevard in 1993. (Joaquin, 19 at the time, made the anguished 911 call.) But it also comes from the fact that he’s noticeably uneasy accepting what he sees as the fake confines of the celebrity interview. He talks about it now: the photo shoot he just endured for this piece, sitting here in this office with me, trying to form answers to questions that don’t really mean anything to him. (‘‘Everyone lies on talk shows,’’ he told Ellen DeGeneres in 2015 when he was promoting ‘‘Inherent Vice.’’) When flailing for an answer about the perils of doing publicity and his refusal to get comfortable with the fitting of suits and posing amid the flashes of cameras on red carpets, he finally admits, in a high strangled voice, that this reluctance might stem from ‘‘some antiquated idea of rebellion as I plummet into middle age, desperately clinging to something.’’

His performances are inquisitive and improvisatory, and he’s resolutely a screen actor. (When in talks about doing a play, Phoenix learned how long the run would be: ‘‘ ‘At least five months?!’ I said, ‘You’re outta your mind!’ ’’) Time means more to him now than it ever has. When asked if he’d ever do a Marvel movie, he says, ‘‘Something that’s going to demand six months of my time? I don’t know.’’ Part of his reluctance to discuss acting is that he works in an intuitive, untrained way, lately in idiosyncratic, large-scale auteur movies helmed by James Gray and Paul Thomas Anderson. ‘‘It’s just instinct,’’ he says. He has no idea where his craft comes from. He’s suspicious of the actor who ‘‘nails’’ it, and he doesn’t like rehearsing: ‘‘If I figured it out, I would be much happier and more confident and less anxious every time I work. But I enjoy not figuring it out. Bad acting is being self-conscious. Sometimes it’s a couple weeks on set before it feels like I find something.’’

‘‘The best directors I’ve worked with always adjusted to what was happening with the actor,’’ he says. For Phoenix, a great performance is in the director’s hands — it’s ultimately the director’s world he’s entering. ‘‘On set I’ve seen things when actors have given great *performances and once it’s cut together you don’t feel it, you don’t care. I’ve done stuff that I thought was garbage and then it’s put together and it’s really effective.’’ He says this with a combination of sincerity and befuddlement, as if he’s caught between two truths. ‘‘When I was younger I thought the idea was to construct a character, figure out its arc — now I think arcs are kind of BS. The director creates the arc.’’

HE’D BEEN ACTING since he was 8 (his first big movie was Ron Howard’s 1989 ‘‘Parenthood’’), but it wasn’t until Gus Van Sant, who had directed River in ‘‘My Own Private Idaho,’’ tapped into Joaquin’s raw adolescent beauty in 1995’s black comedy ‘‘To Die For’’ that he became a young actor you couldn’t ignore. He was handsome in ways different from his brother, who could easily convey a pure all-American blond boyishness. Joaquin’s beauty was darker, impish and marked with a satyr’s smile, the scar above his upper lip adding a sense of menace — there was something sweetly unsettling and endlessly vulnerable about him. ‘‘Gladiator,’’ in 2000, made him a star, and he followed it with big hits like ‘‘Signs’’ (2002), ‘‘Walk the Line’’ (2005) and ‘‘We Own the Night’’ (2007). There’s a refusal to make himself likable or relatable — it’s hard to think of another current American leading man who asks for less of our love than Phoenix — and yet in James Gray’s ‘‘Two Lovers’’ (2009), in which he plays a suicidal photographer, he’s as sympathetic and endearing as any actor of his generation.

The critically reviled and little-seen ‘‘I’m Still Here,’’ from 2010, marks the divide between early Phoenix and the magisterial performances he gave afterward: ‘‘The Master,’’ in 2012, ‘‘Her’’ and ‘‘The Immigrant,’’ in 2013, and ‘‘Inherent Vice,’’ in 2014. Directed and co-written by Casey Affleck (then Phoenix’s brother-in-law), ‘‘I’m Still Here’’ is a mockumentary purportedly chronicling Phoenix’s ‘‘breakdown’’ in the fall of 2008 and into 2009: an anarchic act of self-*destruction, part prankster art piece, part scathing Hollywood satire — and one of only a handful of great films about celebrity. The movie follows a character named Joaquin Phoenix, who tells everyone he’s quitting acting to embark on a career as a hip-hop artist. The movie presents this ‘‘real’’ Joaquin as a paranoid megalomaniac, a self-absorbed jerk, smoking weed, snorting coke, inviting hookers over, missing Obama’s inauguration because he overslept (at one point, while leaving Washington, he wails in despair that ‘‘Tobey and Leo’’ are on a private jet while he is in a ‘‘rent-a-car minivan!’’) and climaxing with a disastrous solo-rap performance in Vegas.

It’s one of his finest performances — naked, hilarious, obscene, an act of mad self-immolation. Any trace of magnetic sexy leading man is erased: fat and bearded with a matted rat’s nest of dreadlocks, disheveled and ranting, Phoenix is at the center of this elaborate hoax, one so poker-faced that it caused epic confusion in the entertainment press as it was being shot. Playful but lacerating, it’s a riveting spectacle of celebrity burnout that seems both real and staged, and for anyone who has been in proximity to the L.A.-N.Y.-Vegas-Miami orbit of youngish celebrity, the movie is unnervingly authentic. It reaches its peak with the infamous David Letterman interview with ‘‘Joaquin,’’ ostensibly there to promote ‘‘Two Lovers’’: sullen, mumbling, chewing gum, refusing to remove his sunglasses, barely interacting with Dave — the audience tittering uncomfortably — and then lashing out at him. The interview made Phoenix more famous than he’d ever been, and was endlessly parodied around the globe.

When asked why he felt the need to make ‘‘I’m Still Here,’’ he says the process was ‘‘terribly humiliating’’ but that he thought it was important to do. Phoenix says it started as a joke, a 10-*minute short in the vein of a ‘‘Saturday Night Live’’ skit, but that Affleck pushed Phoenix to announce he was retiring from acting to a TV reporter. Phoenix didn’t think it would go anywhere, and instead it went viral, and the idea for an actual feature grew from the media’s response: the notion being that Phoenix gives up his career and then desperately tries to get it back, all of this invented but played straight in public. Phoenix was aware the movie might fail but it was also the ultimate distillation of how he likes to work. ‘‘An amazing experience: not finding your light, not hitting the mark, not memorizing lines,’’ he says. ‘‘It allowed me to be bold in my decisions instead of being safe.’’

For two years after, he didn’t work, even after admitting ‘‘I’m Still Here’’ was a stunt. There were offers, but nothing he would have considered. When he returned it was as Freddie Quell in ‘‘The Master,’’ the drunken disciple of Lancaster Dodd, an L. Ron Hubbard-esque cult leader played by Philip Seymour Hoffman. Many consider this Phoenix’s greatest performance — he had lost all the weight from ‘‘I’m Still Here’’ and appears taut, almost gaunt. Perhaps his most powerful scene on film is the ‘‘processing’’ sequence, with Dodd intensely interrogating Quell about his troubled childhood, the camera staying close on Phoenix as his innocence morphs into possessed rage.

HE ADMITS HE HAS a mortgage and that he needs to work but adds that ‘‘I never did anything for money,’’ and when you look over his filmography, you realize this is probably true. When asked why he decided to play Jesus in the upcoming ‘‘Mary Magdalene,’’ a retelling of the New Testament story by the director Garth Davis, he says, ‘‘I was looking for something meaningful. I was looking for an experience. I was friends with Rooney.’’ (Rooney Mara plays Mary Magdalene in the movie. The two are now a couple.) Jesus, in the film, is ‘‘just a man’’ and playing him was ‘‘just instinct, just a gut feeling.’’

Phoenix’s life is remarkably simple compared to what people might imagine. He lives with Mara in the Hollywood Hills (he’s never been married and has no children) and is usually asleep by 9 p.m. and up at 6. When he’s not working his daily routine consists of answering emails, ‘‘chilling’’ with his dog, meditating, taking a karate class, eating lunch, reading scripts and dinner — but for most of last year he’d been on location. He watches documentaries on Netflix (and he watched the 10-hour true-crime doc ‘‘The Staircase’’ recently because Mara wanted to) but rarely watches new movies. When asked if any recent films have excited him, he thinks about it, stuck, and then answers, genuinely surprising himself: ‘‘ ‘Moana’! I thought it was beautiful.’’ (He later corrects himself and says it was actually ‘‘The Lost City of Z,’’ James Gray’s latest — Phoenix has starred in four of Gray’s seven films.)

Twelve years ago Phoenix went into rehab for alcoholism. ‘‘I really just thought of myself as a hedonist. I was an actor in L.A. I wanted to have a good time. But I wasn’t engaging with the world or myself in the way I wanted to. I was being an idiot, running around, drinking, trying to screw people, going to stupid clubs.’’ There was no intervention, Phoenix says, he just checked himself in. ‘‘I thought rehab was a place where you sat in a Jacuzzi and ate fruit salad. But when I got there they started talking about the 12 steps and I went: ‘Wait a minute, I’m still gonna smoke weed.’ ’’ He offers a startled, questioning look, and then later admits: ‘‘I think at the core of the program is a spirituality that is important to me, but . . . I am a hippie, you know.’’ Though he still drinks when he flies (the last drink he had was a month ago on a flight to *London) he has stopped smoking marijuana. ‘‘There’s too many things I enjoy doing and I don’t want to wake up feeling hungover. It’s not a thing I fight against — it’s just the way I live my life. Some of it’s probably age.’’

Spike Jonze, who directed Phoenix in ‘‘Her,’’ has said that the actor is the most unpretentious person he has ever met, and you’re reminded of this when hanging with Phoenix — he is constantly searching, relentlessly earnest, almost childlike, the long answers circling back upon themselves — and as the conversation continues, he slowly slides down the back of the chair until he’s almost lying in it, casually unaware, occasionally reaching over to tap the ash from the cigarettes he keeps lighting into a plastic cup filled with water. Phoenix doesn’t pretend to have answers to anything, and when asked about the political divide in the country, he says, ‘‘I don’t think I’m anything other than another idiot yapping his opinion. I probably don’t know enough to say anything, I’m embarrassed to say.’’ He’s equally self-deprecating when he’s asked about having an obligation to his fans. ‘‘What fans? I have about three. And one of them is my mother.’’ But when he’s asked if he felt overly self-conscious when he was chosen to play Jesus, he says, simply, ‘‘No.’’ He looks at me, somewhat perplexed: ‘‘I thought: Finally, someone gets me.’’

nytimes