Drawn to Trouble

By DEBORAH SOLOMON

Published: September 4, 2005

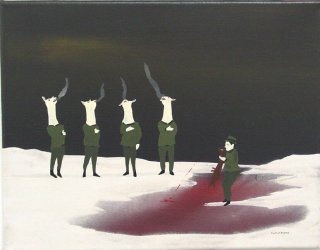

When you first see the art of Marcel Dzama, you may feel you are looking at illustrations from some quaintly antique children's book. He specializes in pen-and-ink drawings in which pale, slender women routinely meet up with rabbits and talking trees. Yet Dzama isn't making art for children.

He uses his innocent-looking style to capture a savage contemporary universe, a place that is grimmer than any Grimm's tale. It's as if you have wandered off the proverbial path to grandmother's house and stumbled upon some secret internment camp where bossy personality types (men with rifles, flying bats) oversee the wounded and the weak.

Dzama is a Canadian

Wunderkind, and his lugubrious fairy-tale sensibility in some way exemplifies the latest drift in contemporary art. Call it cute tragedy or tragic cuteness: either way, it refers to the impulses of a post-Warhol generation that uses the popular art forms of childhood to express a startling array of adult feelings. Dzama's audience extends well beyond the art world, and he has lately become the illustrator of choice for any number of contemporary writers and musicians. He has provided drawings for a CD by Beck, a collection of music essays by the novelist Nick Hornby and a gothic history of the American presidency by Sarah Vowell. His democratic instincts have also led him to design household items, including salt and pepper shakers in the form of crying ghosts, blue tears steaming down their porcelain cheeks.

''I like the idea of making products that my family can use,'' Dzama commented with apparent earnestness when we met not long ago in his studio in SoHo. At 31, the artist is tall and lanky, with dark hair and a quietly charming manner. His studio is an extension of his work, an inspired space where normally uninteresting objects -- a battered suitcase, an electric fan -- possess painted-on expressions that convey their apparent displeasure at being trapped in their inanimate bodies. Even the artist's name sounds slightly invented. Wasn't Marcel reserved for hypercreative Frenchmen, for Proust and his cronies? '''Marcel Duchamp' was the first art book that I took out of the library, but I'm not sure that I really got it back then,'' said Dzama, whose Polish last name is pronounced with a silent d and rhymes with llama.

Of all his undertakings, Dzama's most memorable are surely his stand-alone drawings, a cache of which will go on view at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York this week. The new drawings -- whose colors are mostly restricted to olive greens, vermilions and fuzzy-looking browns made from a root-beer base -- are reminiscent of the illustrations that filled books and magazines around 1900, when three-color printing was considered a novelty. Yet here the Beatrix Potter style is put in service of a 21st-century tale about violence and its sorrows, a cryptic narrative that seems to touch on everything from the prison abuses perpetrated by soldiers in Iraq to the private and largely psychological arena where children are wounded by careless adults. Here, childhood, too, is a country all its own where unspeakable events occur and there are no flights out.

The same characters appear and reappear from one drawing to the next. The men are mostly blustery, virile types -- there are old-time gangsters and big-band musicians, a posse of cowboys with ample mustaches aiming their rifles at a descending front of bats. The women also inflict cruelties or endure them. They variously carry pistols, wear blindfolds or hang limply from the branches of a concerned-looking tree with a human face. ''When you're alone in the woods, you always see faces,'' Dzama told me, making it sound as if even his most surreal drawings have their roots in autobiography.

Born in 1974 in the isolated Canadian wilds of Winnipeg, Dzama grew up in a working-class family, the oldest of three children. His father, a baker, worked behind the cake counter at a Safeway supermarket. (''I made friends with the cake decorator, and she would give me gingerbread all the time,'' the artist said.) He recalled himself as a tense, dyslexic youth who had trouble decoding basic sentences and dreaded the pressure of having to stand up in front of his classmates to read a passage from Shakespeare aloud. Early on, he took refuge in drawing; he started a comic strip about his teddy bear, ''whose name happened to be Ted,'' he said.

He earned his first fame in 1996 as a senior at the University of Manitoba. There he founded the Royal Art Lodge, an ironically named collective that can put you in mind of hunters and wild boar. But this lodge's members wielded colored pencils, and they sat around late into the night, often working on one another's compositions; in coming years, they would exhibit together as well, locally at first and then at galleries in Los Angeles, New York and London. Two years ago, Dzama started a second collective, the Royal Family, a touchingly homey enterprise for which he enlisted his sister Hollie; his uncle Neil Farber; his future wife, Shelley Dick; and even his mother, Jeanette, who has designed and sewed many of the furry, life-size costumes of bears and alligators that appear in her son's video productions.

Last November, just before another long winter set in, Dzama decided to leave Winnipeg for New York. It was the first time he has lived away from home, and one of his recent works refers directly to his departure. ''Snowman Canisters,'' as it is called, actually consists of a set of usable kitchen canisters, mass- -- or at least semi-mass- -- produced in an edition of 2,500 by a Philadelphia-based company called Cereal Art.

The canisters acquaint us with a fetching snowman -- or is he a penguin? -- in four different incarnations, each a little smaller. With his lopsided black ovals for eyes and his inky nose, he is a figure of pathos, melting from robust and dignified manhood into a shapeless lump of snow.

Dzama spoke of the piece as a personal farewell to chilly Winnipeg and his entire Canadian past. Yet even the past is never really past, as that other Marcel, the author of ''Remembrance of Things Past,'' was always reminding us. You can see the canisters as a tribute to Dzama's baker father and perhaps also to the countless pairs of anonymous hands that measure out cups of flour and sugar every day, making homespun birthday cakes and preserving one of the sweetest rituals of childhood.

In his art, Dzama tries to keep that world and its enchantments alive, even though he knows that the candles were long ago blown out.

[FONT=Arial, Helvetica, San Serif][SIZE=-1]Dzama in his studio. The tree is a costume for a new Beck video.

[/SIZE][/FONT][FONT=Arial, Helvetica, San Serif][SIZE=-1]Dzama's SoHo studio is occupied by an army of chaming and sinister characters.

[/SIZE][/FONT][FONT=Arial, Helvetica, San Serif][SIZE=-1]

Dzama in his studio.

[/SIZE][/FONT][FONT=Arial, Helvetica, San Serif][SIZE=-1]

Some of the characters are working objects, like the salt and pepper shakers.

[/SIZE][/FONT][FONT=Arial, Helvetica, San Serif][SIZE=-1]

Others are parts of works in progress.[/SIZE][/FONT]

Apparently his art provides a theraputic outlet for past disturbances, in particular a traumatic 'incident' with a baby-sitter which he refers to only in ambiguous terms. It's interesting, I'll search for it. In the meantime, I love the nightmare-childhood aspect of his work, toys turned sinister, etc. Thanks for the topic anna, I'm really a huge fan - a really huge fan. Really.

Apparently his art provides a theraputic outlet for past disturbances, in particular a traumatic 'incident' with a baby-sitter which he refers to only in ambiguous terms. It's interesting, I'll search for it. In the meantime, I love the nightmare-childhood aspect of his work, toys turned sinister, etc. Thanks for the topic anna, I'm really a huge fan - a really huge fan. Really.