rangerrick14

Member

- Joined

- Dec 20, 2005

- Messages

- 624

- Reaction score

- 1

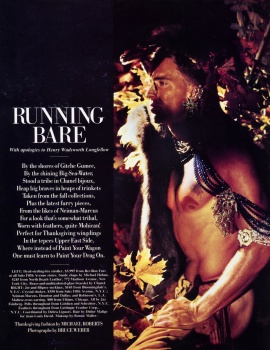

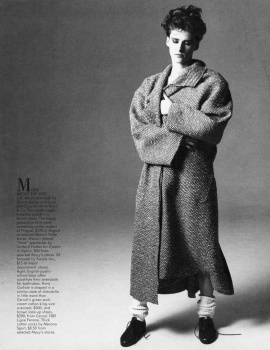

I searched and searched but to no avail I did not find a thread on Michael Roberts. So here we go...... lets get started on the great unsung Renaissance man of fashion. And black to boot. He is a source of inspiration to a young black boy wanting to break into the world of fashion. He has worn many hats from writer, stylist, illustrator, photographer and editor and all of them worn well.

I found this article with Q&A between him and cathy Horyn.

Enjoy!!

Q and A: Michael Roberts

Michael Roberts attending the Dolce & Gabbana 20th Anniversary in Milan. (Uno Press/WireImage)

Michael Roberts attending the Dolce & Gabbana 20th Anniversary in Milan. (Uno Press/WireImage)

I knew Michael Roberts’ work as a writer, photographer, stylist and illustrator long before we were introduced in the late 1990s. Were we introduced? Or did we meet one day at a fashion show and just start talking? We quickly discovered that we had a link to the same unpublished Vivienne Westwood profile, for Vanity Fair, in the mid 90s. I had been asked to write a profile of Westwood, which I did, but publication of the piece was delayed and delayed until, eventually, the editorial window closed for her. Michael had photographed her—appropriately, under glass. He had found an enormous bell jar and Westwood had gamely consented to be photographed as if her head were a museum specimen. Or an offering at a pagan feast, brightly colored. She is a genius.

Michael is a rare fellow in the fashion world. He has a great mind and a great wit. He is incredibly decisive. He knows why something is the way it is and he can draw on his vast store of memory to further explain things. He is currently the fashion director of Vanity Fair, but he has also worked for The New Yorker, Tatler and the London Sunday Times. In 2005, Edition 7L published “The Snippy World of New Yorker Fashion Artist Michael Roberts,” a collection of his drawings and collages. Next month, in New York, 7L (Lagerfeld’s imprint) will bring out “Shot in Sicily,” a book of his photographs taken over 20 years. I sat down with Michael in Paris to talk about Sicily — and, along the way, Irvin Penn, Helmut Newton and the state of fashion.

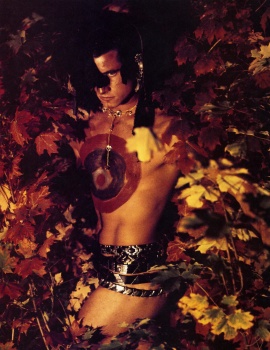

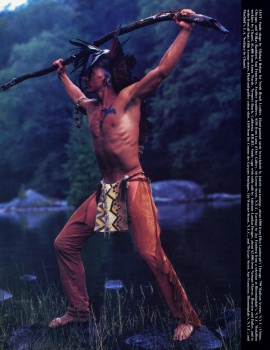

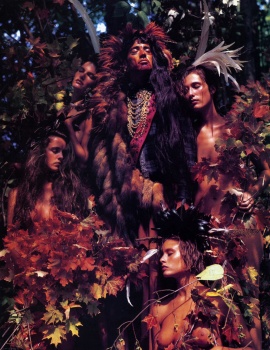

See photos from Michael Roberts’ book “Shot in Sicily.”

CH: When did you go to Sicily for the first time?

MR: Easter, 1987. I was on holiday in Venice for a few days with a friend, Martha Fiennes, sister of Ralph Fiennes, and we had three more days. Couldn’t decide where to go. So I said, “Let’s put on a blindfold on and stick a pin in the map.” Just like that. We put the pin on Messina, on the tip of Italy. Driving into Taormina, I had this weird feeling I had seen it before, like the first time I went to New York. I just completely loved the landscape. I went back in the summer and did a whole series of photographs. Then gradually I got to know the people.

Q: A lot of fashion people have discovered Sicily, exposing it. Have you seen a change?

A: Subliminally, I’ve seen a lot of change. But my vision of it has been so determinately the one I started with that I tended to block the other stuff out. You may call my vision of Sicily very clichéd, but it is the Sicily that certainly existed once and in a way still does. I’ve edited out the plastic, the bad discos and terrible clothes. And I always knew I was going to do a book. It’s completely idealized but it doesn’t make it any less true.

Q: How do people in Sicily like having their pictures taken?

A: Now I think I’m a little bit known there, so it’s okay. Of course, 20 years ago, I had the courage of being much younger, so I just assumed that everyone wanted to be photographed anyway! The older women in black often don’t like being photographed. They’re wearing black because they’re widows, they’re in mourning and they’re mourning for the rest of their lives. So it’s a bit intrusive to run up to people and say how fabulous they look in their black clothes. They’re actually attending a permanent wake.

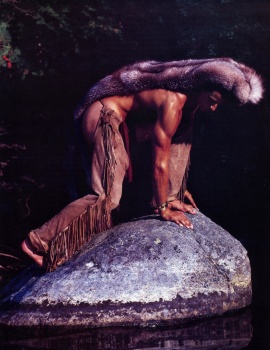

Q: The people in the photographs are so stunning you often can’t tell who’s a model and who’s a local. Like the garage mechanic. Was he conscious of his good looks?

A: Absolutely not. He was in training for bodybuilding, and he had arranged his T-shirt himself. When Armani saw the shirt, he said, “I must use that in my next collection.” And he did. I saw it in Emporio. Like, a week ago! I photographed the guy regularly over the next 10 years.

Anyone who goes to Taormina is very much aware of the work of a German photographer called Baron Von Gloeden. A turn-of-the-century baron who went there and photographed the locals, young boys and girls, in Greek mythic poses, wearing something like a fig leaf. He became incredibly famous there and people like Queen Victoria collected his art photography. Oscar Wilde visited Sicily just to meet him. I did a whole series based on his kind of look. He was ex-communicated by the Catholic church, and when the Nazis invaded Sicily, they crushed 3,000 of his glass negatives. I always thought he would make a fantastic movie.

Q: What do you like about contemporary photography?

A: I like a lot of the photography that is very, very artificial, I suppose. I like Mert and Marcus, because they’re so stripped down to a perfection of glamour. Which is what selling clothes is about. It’s so slick that it’s like looking at a new iPod. You can marvel at the technological wonder of it. And, of course, like an iPod, it’s not a lasting love. You love it for its moment.

In terms of pure photography, you can’t fault someone like Penn, who was doing that kind of perfection in 1945, and is still doing it today. This is a person like Picasso. He has an incredible eye. He’s a genius.

Q: I’d love to meet Penn.

A: He’s an amazing person to talk to. When I was first at Vanity Fair, years ago, I was constantly making trips to Mr. Penn’s studio to talk him into doing things. He wasn’t ‘talked to’ at all in those days. He’d just say, “I want to do this,” and the conversation would be closed. But when I was at The New Yorker, maybe 20 years later, and I had to go down and talk to him, he was much more amenable. He loved talking. He still wouldn’t do the things [laughs] but he’d give you a very gracious four hours explaining why he wouldn’t. I treasure my conversations with Penn.

There are three things I will keep forever. One is a very complimentary letter from Avedon about something that I had done. Another is a letter from Saint Laurent, and the third is an amazing letter from Penn. He sent me a letter about the book of cutouts.

Q: What example does Penn set?

A: The absolute pursuit of excellence. It’s crystalline. It makes me think of Vreeland’s statement that “style is refusal.” That’s exactly what Penn does. It’s the denial of excess, of things, of excess light. There’s no one—not even Avedon—who approaches that. The denial of ego also comes through Penn’s work. Penn always gives the impression that no ego is involved. In Avedon’s work, I think, the ego gets in the way. A big ego was always in the way. He was that kind of guy. It was always “Me, me, me.” Maybe inwardly, Penn is shrieking “Me, me, me,” but it certainly doesn’t come through in his work.

Q: We have a lot of egos in fashion, but it’s interesting to see who is able to renew himself and take risks and not repeat.

A: Refining yourself is not repeating yourself. Yes, Penn has his way, but he’s refining himself. You know, he does marvelous doodles. He draws things out. Helmut Newton’s way was to rip things out of newspaper and remember them for later, so he’d have an image in his mind. Of course, the picture he did never really looked like the newspaper image. It would always be Helmutized. He was the one who inspired me to be a photographer. He said two things to me. He said, “When they tell you there’s no light, don’t believe them. There’s always enough light.” And the other was, “You don’t need more than two rolls.” In the end, you only need one frame. He got all those night pictures of Paris by knowing there was enough light from the street lamps to take a picture.

Q: In school, you started as an illustrator. Then you became a writer [for the London Sunday Times], then a stylist, then a photographer. You’ve also been an art director and now you’re back to taking pictures. What if you had stayed with one thing?

A: That was never an option, I suppose. I like painting, but I knew I would never be just a painter. I felt the same about illustration. All the stuff I do relies on having the idea. They are idea-driven things.

Q: I remember seeing you at lunch at Alaia’s cutting out your collages at the table.

A: Endlessly! The collages very much had to do with the fact that I was at the New Yorker, and the magazine doesn’t have much call for fashion photographs. It’s the home for illustration and drawings. I was committed to doing covers. I ended up doing 22 of them. People say, “Oh, you jump from one thing to another.” I don’t see it as jumping from one thing to another. I see them all as branches of the same thing. And when I’m tired of sitting on that branch, I can run to the other.

Q: What’s the biggest change you’ve seen in the fashion world in the past 35 years?

A: Fashion has never been more popular, I think. It ceased to be a very exclusive thing. There’s Karl doing H & M, Kate doing Topshop. It’s almost become nauseatingly widespread. Sometimes I long to get away from it. That’s a huge difference from when I started. I came in as assistant at the Sunday Times to a very famous editor, Molly Parkin, who started a magazine called Nova. We’d go to Paris for the couture. It was a whole hierarchical world in those days. There were huge power figures in terms of journalists. I’m talking about the early 70s. John Fairchild. There was Vreeland sitting on a couch at Saint Laurent. All these dragon ladies, endless dragon ladies. There were the first rumblings of ready to wear.

Q: Fashion’s universality is relatively new.

A: I do find that fashion is much less about the designers. That’s a huge change. Even though I never became a designer, I spent three years learning how to make clothes—how to ease in a sleeve, how to put in a bust dart. When I look around, years and years later, fashion has nothing to do with that world anymore. It’s all to do with “mood boards.” A picture by Man Ray, a clipping from a magazine…The mood board is a substitute for not knowing how to make something. I mean, that’s a huge difference—you don’t need to know how to make something to be a fashion designer.

Q: What’s your next book?

A: It’s going to be called “You’re Only Young Once.” I’ve done lots of pictures of young stars at the beginning of their careers, like Brad Pitt and Jude Law. I’ve also got lots of pictures of young people behaving as young people do. Food fights in Paris. In initiation at a Louisiana university, where people are completely out of their heads. The youngest matador in the world, a 15-year-old, doing his first fight. There’s an incredible hope and daring about everything.

(www.nytimes.com)

I found this article with Q&A between him and cathy Horyn.

Enjoy!!

Q and A: Michael Roberts

I knew Michael Roberts’ work as a writer, photographer, stylist and illustrator long before we were introduced in the late 1990s. Were we introduced? Or did we meet one day at a fashion show and just start talking? We quickly discovered that we had a link to the same unpublished Vivienne Westwood profile, for Vanity Fair, in the mid 90s. I had been asked to write a profile of Westwood, which I did, but publication of the piece was delayed and delayed until, eventually, the editorial window closed for her. Michael had photographed her—appropriately, under glass. He had found an enormous bell jar and Westwood had gamely consented to be photographed as if her head were a museum specimen. Or an offering at a pagan feast, brightly colored. She is a genius.

Michael is a rare fellow in the fashion world. He has a great mind and a great wit. He is incredibly decisive. He knows why something is the way it is and he can draw on his vast store of memory to further explain things. He is currently the fashion director of Vanity Fair, but he has also worked for The New Yorker, Tatler and the London Sunday Times. In 2005, Edition 7L published “The Snippy World of New Yorker Fashion Artist Michael Roberts,” a collection of his drawings and collages. Next month, in New York, 7L (Lagerfeld’s imprint) will bring out “Shot in Sicily,” a book of his photographs taken over 20 years. I sat down with Michael in Paris to talk about Sicily — and, along the way, Irvin Penn, Helmut Newton and the state of fashion.

See photos from Michael Roberts’ book “Shot in Sicily.”

CH: When did you go to Sicily for the first time?

MR: Easter, 1987. I was on holiday in Venice for a few days with a friend, Martha Fiennes, sister of Ralph Fiennes, and we had three more days. Couldn’t decide where to go. So I said, “Let’s put on a blindfold on and stick a pin in the map.” Just like that. We put the pin on Messina, on the tip of Italy. Driving into Taormina, I had this weird feeling I had seen it before, like the first time I went to New York. I just completely loved the landscape. I went back in the summer and did a whole series of photographs. Then gradually I got to know the people.

Q: A lot of fashion people have discovered Sicily, exposing it. Have you seen a change?

A: Subliminally, I’ve seen a lot of change. But my vision of it has been so determinately the one I started with that I tended to block the other stuff out. You may call my vision of Sicily very clichéd, but it is the Sicily that certainly existed once and in a way still does. I’ve edited out the plastic, the bad discos and terrible clothes. And I always knew I was going to do a book. It’s completely idealized but it doesn’t make it any less true.

Q: How do people in Sicily like having their pictures taken?

A: Now I think I’m a little bit known there, so it’s okay. Of course, 20 years ago, I had the courage of being much younger, so I just assumed that everyone wanted to be photographed anyway! The older women in black often don’t like being photographed. They’re wearing black because they’re widows, they’re in mourning and they’re mourning for the rest of their lives. So it’s a bit intrusive to run up to people and say how fabulous they look in their black clothes. They’re actually attending a permanent wake.

Q: The people in the photographs are so stunning you often can’t tell who’s a model and who’s a local. Like the garage mechanic. Was he conscious of his good looks?

A: Absolutely not. He was in training for bodybuilding, and he had arranged his T-shirt himself. When Armani saw the shirt, he said, “I must use that in my next collection.” And he did. I saw it in Emporio. Like, a week ago! I photographed the guy regularly over the next 10 years.

Anyone who goes to Taormina is very much aware of the work of a German photographer called Baron Von Gloeden. A turn-of-the-century baron who went there and photographed the locals, young boys and girls, in Greek mythic poses, wearing something like a fig leaf. He became incredibly famous there and people like Queen Victoria collected his art photography. Oscar Wilde visited Sicily just to meet him. I did a whole series based on his kind of look. He was ex-communicated by the Catholic church, and when the Nazis invaded Sicily, they crushed 3,000 of his glass negatives. I always thought he would make a fantastic movie.

Q: What do you like about contemporary photography?

A: I like a lot of the photography that is very, very artificial, I suppose. I like Mert and Marcus, because they’re so stripped down to a perfection of glamour. Which is what selling clothes is about. It’s so slick that it’s like looking at a new iPod. You can marvel at the technological wonder of it. And, of course, like an iPod, it’s not a lasting love. You love it for its moment.

In terms of pure photography, you can’t fault someone like Penn, who was doing that kind of perfection in 1945, and is still doing it today. This is a person like Picasso. He has an incredible eye. He’s a genius.

Q: I’d love to meet Penn.

A: He’s an amazing person to talk to. When I was first at Vanity Fair, years ago, I was constantly making trips to Mr. Penn’s studio to talk him into doing things. He wasn’t ‘talked to’ at all in those days. He’d just say, “I want to do this,” and the conversation would be closed. But when I was at The New Yorker, maybe 20 years later, and I had to go down and talk to him, he was much more amenable. He loved talking. He still wouldn’t do the things [laughs] but he’d give you a very gracious four hours explaining why he wouldn’t. I treasure my conversations with Penn.

There are three things I will keep forever. One is a very complimentary letter from Avedon about something that I had done. Another is a letter from Saint Laurent, and the third is an amazing letter from Penn. He sent me a letter about the book of cutouts.

Q: What example does Penn set?

A: The absolute pursuit of excellence. It’s crystalline. It makes me think of Vreeland’s statement that “style is refusal.” That’s exactly what Penn does. It’s the denial of excess, of things, of excess light. There’s no one—not even Avedon—who approaches that. The denial of ego also comes through Penn’s work. Penn always gives the impression that no ego is involved. In Avedon’s work, I think, the ego gets in the way. A big ego was always in the way. He was that kind of guy. It was always “Me, me, me.” Maybe inwardly, Penn is shrieking “Me, me, me,” but it certainly doesn’t come through in his work.

Q: We have a lot of egos in fashion, but it’s interesting to see who is able to renew himself and take risks and not repeat.

A: Refining yourself is not repeating yourself. Yes, Penn has his way, but he’s refining himself. You know, he does marvelous doodles. He draws things out. Helmut Newton’s way was to rip things out of newspaper and remember them for later, so he’d have an image in his mind. Of course, the picture he did never really looked like the newspaper image. It would always be Helmutized. He was the one who inspired me to be a photographer. He said two things to me. He said, “When they tell you there’s no light, don’t believe them. There’s always enough light.” And the other was, “You don’t need more than two rolls.” In the end, you only need one frame. He got all those night pictures of Paris by knowing there was enough light from the street lamps to take a picture.

Q: In school, you started as an illustrator. Then you became a writer [for the London Sunday Times], then a stylist, then a photographer. You’ve also been an art director and now you’re back to taking pictures. What if you had stayed with one thing?

A: That was never an option, I suppose. I like painting, but I knew I would never be just a painter. I felt the same about illustration. All the stuff I do relies on having the idea. They are idea-driven things.

Q: I remember seeing you at lunch at Alaia’s cutting out your collages at the table.

A: Endlessly! The collages very much had to do with the fact that I was at the New Yorker, and the magazine doesn’t have much call for fashion photographs. It’s the home for illustration and drawings. I was committed to doing covers. I ended up doing 22 of them. People say, “Oh, you jump from one thing to another.” I don’t see it as jumping from one thing to another. I see them all as branches of the same thing. And when I’m tired of sitting on that branch, I can run to the other.

Q: What’s the biggest change you’ve seen in the fashion world in the past 35 years?

A: Fashion has never been more popular, I think. It ceased to be a very exclusive thing. There’s Karl doing H & M, Kate doing Topshop. It’s almost become nauseatingly widespread. Sometimes I long to get away from it. That’s a huge difference from when I started. I came in as assistant at the Sunday Times to a very famous editor, Molly Parkin, who started a magazine called Nova. We’d go to Paris for the couture. It was a whole hierarchical world in those days. There were huge power figures in terms of journalists. I’m talking about the early 70s. John Fairchild. There was Vreeland sitting on a couch at Saint Laurent. All these dragon ladies, endless dragon ladies. There were the first rumblings of ready to wear.

Q: Fashion’s universality is relatively new.

A: I do find that fashion is much less about the designers. That’s a huge change. Even though I never became a designer, I spent three years learning how to make clothes—how to ease in a sleeve, how to put in a bust dart. When I look around, years and years later, fashion has nothing to do with that world anymore. It’s all to do with “mood boards.” A picture by Man Ray, a clipping from a magazine…The mood board is a substitute for not knowing how to make something. I mean, that’s a huge difference—you don’t need to know how to make something to be a fashion designer.

Q: What’s your next book?

A: It’s going to be called “You’re Only Young Once.” I’ve done lots of pictures of young stars at the beginning of their careers, like Brad Pitt and Jude Law. I’ve also got lots of pictures of young people behaving as young people do. Food fights in Paris. In initiation at a Louisiana university, where people are completely out of their heads. The youngest matador in the world, a 15-year-old, doing his first fight. There’s an incredible hope and daring about everything.

(www.nytimes.com)

Last edited by a moderator:

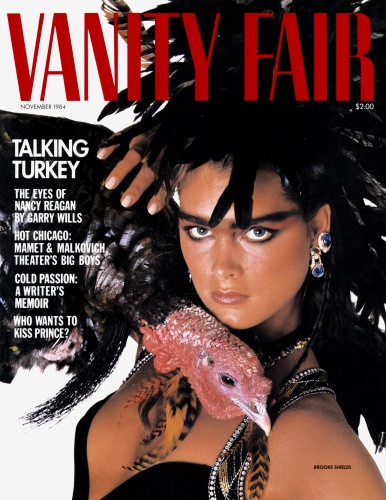

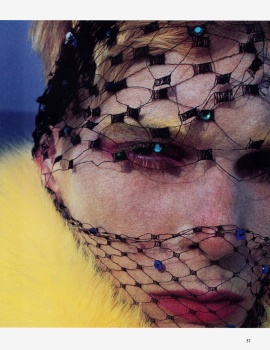

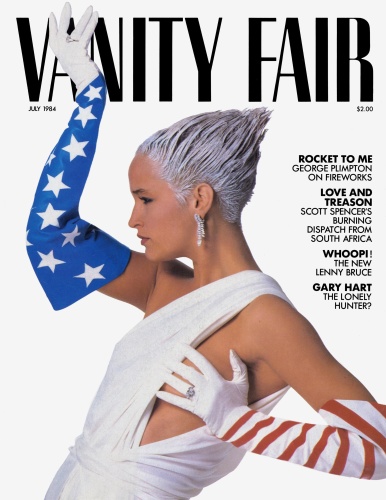

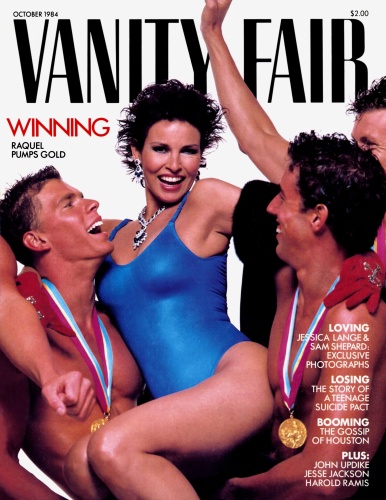

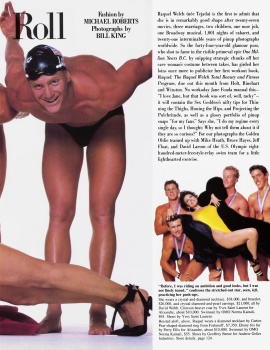

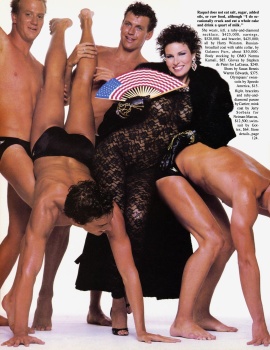

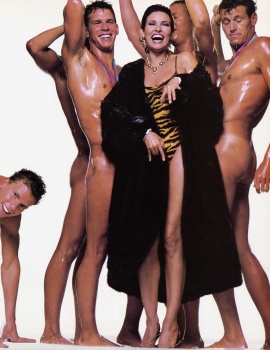

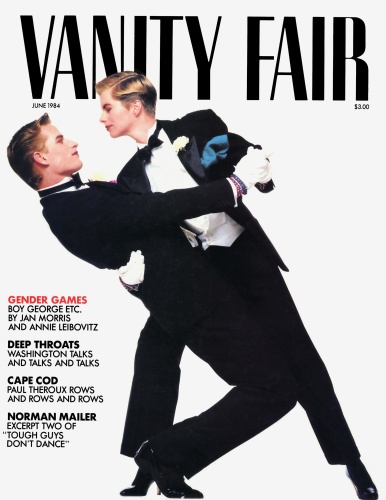

gemma's vanity fair cover which is styled by him

gemma's vanity fair cover which is styled by him