Pascal Dangin is the photo-retoucher.

He is responsible with retouching every Vogue cover (for which he charges 20,000 dollars) to every Annie Leibovitz, Patrick Demarchelier, Steven Meisel, Craig McDean and Steven Klein photo. He is an enigma, a myth, an unspoken secret. The things this man is capable of doing is beyond anything imaginable. He makes stars look like stars and the sole reason why models do not need to retire anymore.

May 18, 2008

The Sunday Times

source:

http://women.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/women/celebrity/article3953925.ece

He is responsible with retouching every Vogue cover (for which he charges 20,000 dollars) to every Annie Leibovitz, Patrick Demarchelier, Steven Meisel, Craig McDean and Steven Klein photo. He is an enigma, a myth, an unspoken secret. The things this man is capable of doing is beyond anything imaginable. He makes stars look like stars and the sole reason why models do not need to retire anymore.

May 18, 2008

The Sunday Times

Pascal Dangin: the master manipulator

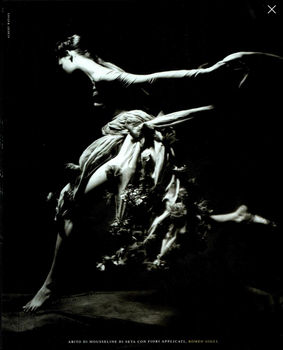

Pascal Dangin, the ‘retouch’ artist most sought by celebs, has sparked a debate on how far images are digitally altered Dove's 'real women' advert, with Dangin's head digitally imposed on one of the women

by Camilla Long

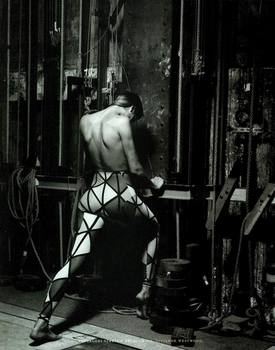

Inside an old warehouse in New York is a man who can make any woman beautiful. Sculpted cheekbones, slimmer waist, bigger bust or more smouldering eyes — Pascal Dangin can deliver them all.

Dangin is the master magician of “retouching” images by computer manipulation. He is sought out by top photographers such as Annie Leibovitz and Stephen Meisel and by film stars and models who seek perfection — or at least the impression of perfection.

In Dangin’s world nothing is quite what it seems. Last week he let slip in a rare interview that he had tinkered with the Dove cosmetics campaign featuring “real women”. Speaking to The New Yorker magazine, he was quoted as saying: “It was great to do, a challenge, to keep everyone’s skin and faces showing the mileage but not looking unattractive.”

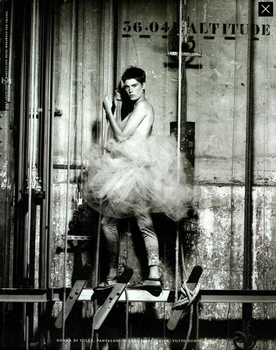

Glossy magazines and advertising campaigns have long relied on the retoucher’s skill and Dangin manipulates countless images for international editions of Vogue magazine. In the March issue of US Vogue alone, he digitally tweaked 107 advertisements, 36 fashion pictures and the cover image of Drew Barrymore.

However, the Dove case was different: the claim that he had applied his skills to a campaign whose very existence challenged the principles of retouching stirred controversy — as well as a denial from the company itself.

Dangin, said the company, had worked only on another of its campaigns, “Dove pro-age”, helping merely with the “removal of dust from the film and minor colour correction”.

It added: “Dove strives to portray women by accurately depicting their shape, size, skin colour and age.”

Nevertheless, the spat brought home the opposite point: these days almost everything goes under the digital knife and so skilful are retouchers such as Dangin that you will never see the scars.

Even Elizabeth Hurley, who recently revealed that she retouches her own holiday snaps, expressed astonishment at how widespread and comprehensive the practice has become. “The manipulation you can do,” she said, “you can completely restructure a person.”

Although artists of Dangin’s calibre are prized for their subtlety, there are now almost no limits on what they can do thanks to the power of the latest technology.

Computers can banish wrinkles, slim down limbs and paint on make-up; they can plump up breasts, add volume to hair, fatten hips and enhance cleavage; they can remove cigarettes, tattoos or other items deemed unsuitable. They can even splice together facial features from separate images of the same person to create an ideal end product.

According to Dangin, the only public figure whose image tends not to be manipulated is the Queen.

Critics say that idealised images created by computers make for impossible role models. But if we know that every image is manipulated, does it matter? Are we not able to distinguish dream from reality?

Image manipulation has always gone on: in classical times, statues of emperors were created along ideal lines rather than any kind of verisimilitude. A bust of Julius Caesar found in the Rhône this week was unusual in that it portrayed the ageing military commander’s wrinkles. Almost as soon as photography began, practitioners began manipulating prints.

The computer, argue some, has merely made the retoucher’s art more sophisticated. Dangin recently demonstrated this with a photograph of a famous actress standing on a skyscraper.

First he shuffled the buildings behind her into a more pleasing arrangement and made the yellowy sky whiter. Then he fluffed out her dress with a “warping” tool.

He softened her collarbones, then thought that she looked a bit too retouched and made them bonier again.

He carefully left her crooked bottom row of teeth alone. “Her face is too high and elongated,” he said. “But I don’t want her to become someone else.”

Dangin has been known to work for days trying to turn grass into the “most expressive” shade of green and cannot bear misaligned windows. Untruthful? Misleading?

“Humans have long colluded in an ideal of beauty,” said Sally Brampton, the writer and former editor of Elle. Her first job was on Vogue in 1978 where she worked alongside two people dedicated solely to airbrushing images. “I am sure Helen of Troy was not that beautiful; we just buy into a collective ideal. Retouching is neither good nor bad: it is clearly something we want and until we decide we don’t want it, it will remain that way.”

So Kate Winslet’s legs are lengthened, Penelope Cruz’s eyelashes are thickened and Mariah Carey expresses an unashamed love of Photoshopping.

“Although you know it’s cheating, it’s gorgeous [to have it done],” admitted Tamara Beckwith, the party girl. “I did a job with Davina McCall to promote something and we both needed to wear white Wonderbras. She’s quite busty and I’m not.

“But when I had a look at the pictures, suddenly I had this gorgeous cleavage. You want more and more.”

Beckwith, however, is also wary of the influence on others. “Young people who don’t have a clue about the fashion world may not understand,” she said. “You can’t sit there and pretend it’s all good.”

Indeed, the British Fashion Council was recently moved to warn magazine editors not to let retouching run out of control. Rosie Boycott, the former magazine and newspaper editor, goes further. “I don’t agree with retouching, although I can see why it happens,” she said. “I think it’s fair enough when it comes to [removing] blemishes, but it gives people unattainable ideas of beauty.

“I don’t like the whole way a star is presented to you: the package, the control.

It’s just become an exercise in PR; retouching happens all the way through.”

Juergen Teller, the photographer, who is renowned for not retouching his pictures, said: “I don’t see a need for it; it’s not what I find beautiful. Sometimes I am astonished. Beauty advertisers change everything and it doesn’t do any good for the psyche of a woman.”

On occasion retouching can deceive even celebrities as well as the public. There was uproar when a magazine digitally removed Kylie Minogue’s knickers for one of its covers and Cat Deeley was horrified when she posed for a photo shoot only to discover later that most of her clothes had been erased.

Photography and fashion industry leaders claim that today’s audiences are sophisticated enough to know the score and understand that they are buying a dream, not reality.

“A certain amount of retouching has always been a part of not only glossy magazines but all glamorous and celebrity- oriented material,” said Alexandra Shulman, editor of Vogue. “We are not in the business of portraying reality all the time and people buy magazines like Vogue in order to look at a kind of perfection.

“They are sophisticated enough to know that what they are seeing is a construct. Nowadays people retouch their own snaps on the computer before posting them on Facebook.”

Jeremy Langmead, editor of Esquire magazine, agreed. “Why shouldn’t you look better? We strive to improve things in other areas of life, so if you have the technology it makes sense,” he said. “If you don’t like retouching you should also be against make- up. And if you want to know what real people look like, you can look out of the window.”

An all-too-stark reality check is also available in magazines such as Heat that specialise in photographs of stars caught unawares. Cellulite, lumpy clothes and pasty faces are all on display among Hollywood actors and models. Some publications even use digital trickery to emphasise these blemishes.

“We know it’s not real, don’t we,” said Brampton. “My 16-year-old daughter accepts that the pictures are fake. She’ll measure herself up to it but not in a damaging way. We fret about teenagers, but they are quite robust and cynical.”

The art of digital manipulation has even come to be regarded with a humorous vanity. That was the reaction of Rachel Johnson, the writer, who was recently photographed for Tatler. “I was very cross,” she said. “I wasn’t retouched! I specifically said, ‘I hope you’re going to do lots of retouching’, but I opened up the magazine and it was warts and all. Yellow teeth, red eyes and thunder thighs. I looked worse than Henry Conway, who was in the same issue.”

Retouching is not always aimed at making women thinner. Fashion insiders say editors often ask for pictures of models to be bulked up, rather than slimmed down, especially if a model has lost weight in between being selected for a shoot and working on the studio session. With thousands of pounds riding on a shoot, boney ankles are not allowed to get in the way of perfection.

As long as we know that we are operating in a Matrix-like parallel universe, the industry argues, retouching does no harm. Dangin said: “I look at life as retouching. Make-up and clothes are just an accessorisation of your being — they are just a transformation of what you want to look like.”

source:

http://women.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/women/celebrity/article3953925.ece

[URL=http://imgbox.com/NXCS0ze8]

[URL=http://imgbox.com/NXCS0ze8]