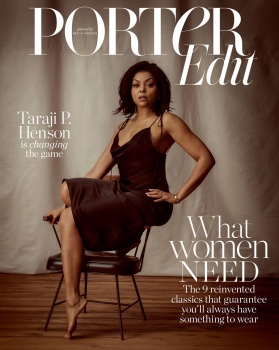

Whether she’s being lowballed by studios, navigating life as a single mother or dealing with tragedy, TARAJI P. HENSON is a woman who knows her own worth, never gives up and always tells it like it is. EVE BARLOW meets a woman who has a lot to teach us.

Taraji P. Henson is a straight shooter. As she sits in the dining hall of Paramount Studios – her hair exquisitely braided, her jacket puffier than a hip-hop mogul’s – you can’t help but think of all the directors, producers and actors who have passed through here. It’s a world that hasn’t been occupied by many women, particularly women who are not white. However, there’s been a shift in (very) recent years, an increased visibility of women of color, and Henson, 48, is at the forefront.

She’s had many golden moments on the big screen, from The Curious Case of Benjamin Button to Hidden Figures, but it’s her small-screen role as Cookie Lyon in Fox’s Empire that has brought widespread recognition. Despite the instant lovability of Cookie, the actress was initially reluctant to take the character on. On paper, she read like someone the audience would hate – a brash ex-convict – but then Henson saw an opportunity to change minds, including her own. “I stopped judging her,” she says. “We see somebody we don’t identify with and the first thing we do is judge, but all we’re put here to do is empathize. It’s my job as the actor to make the audience understand.” She references Charlize Theron in Monster: “We should’ve hated her. But she gave that woman humanity. An actor is supposed to conflict you. You’re supposed to be confused.” There’s a part of Cookie in Henson, too: she’s both a charmer and hustler. This interview is her final appointment of 2018, before she heads to South Africa with her family on vacation, and she’s as gregarious and spicy as if it was her first, offering compliments and hugs. She will tell you exactly what she wants and how she wants it, but make it so entertaining you can’t be mad at her.

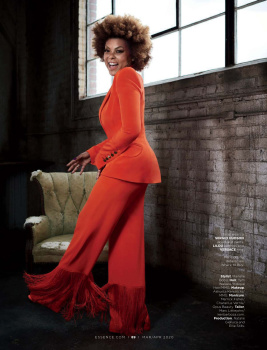

The hustle is perhaps most evident in the way she negotiates her salary, an issue she’s been vocal about since 2008’s Benjamin Button, for which she received an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress. Despite it being her breakthrough role, she wasn’t shy about calling out the pay discrepancy between her and her co-stars. While Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett were reportedly paid tens of millions, Henson was denied the $500,000 fee her agent requested. “I didn’t even ask for one million. But I had to see the bigger picture and bite that bullet,” she says about accepting less. “I knew that if I kept my ego in check I would get the victory. That performance was undeniable. I turned in an Academy-worthy f***ing performance. And what did they say? ‘We shoulda paid her.’” Now, she lives to say ‘no’. “‘They wanna pay what?’” she gasps of the low fees some studios still offer. “‘Honey, a zero is missing. Tell them to go find it then call me back.’ If you come to Taraji P. Henson, you need to come with that money, because I earned it.”

There are no plans for Empire to end soon, but Henson doesn’t want to ride it until the wheels fall off. “Like Sex and the City – I wanna go out on top,” she says. She suggests Empire’s greatest legacy is in proving that any show can be a hit regardless of the cast’s race, citing last year’s blockbuster Black Panther as further evidence. “It was the blackest movie in the world and it did well everywhere,” she says. “People wanna be entertained. They don’t wake up and go, ‘Today I’m gonna see a white movie!’”

In 2018, the actress took Sony to task when she felt that it didn’t market her movie Proud Mary outside of America enough. “That’s what happens with black films,” she says. “They only expect it to do well domestically.” But when Henson started traveling overseas to promote her projects, she realized that theory was nonsense. Not only did people in Europe know her name (“I did the ‘ugly face’ cry,” she says, overwhelmed when fans approached her on the street in London), but she could see for herself that black culture is spread around the world. “I spent three months in China. I went to the clubs. I know what they’re dancing to. I hate pulling the racism card but I’m left with no choice,” she says of calling the studio to account.

She’s happy to see more actresses of color working in prominent roles. She names Gabrielle Union, Vivica A. Fox, Regina King, Tasha Smith and Sanaa Lathan as examples. “Not only are they working, they’re wearing different hats [as directors and producers],” she says. Henson has never pandered to the idea that there isn’t enough room for multiple black actresses. “There was only one role for all of us black women when I came to Hollywood. But I always saw enough work for everyone. I never thought I was fighting. You create your own job. That’s how I was raised.”

Henson grew up in a rough neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Her parents were both grafters; her mother a business manager, her father a janitor. They divorced when she was two years old. In her autobiography, Henson recounts how her father once dragged her mother by her hair and threatened to kill her. Henson was unaware of the abuse as a child, but her dad came clean about it as she got older. They’d discuss his mental-health issues. Henson has been open about her issues, too, and set up a mental-health charity in her father’s name. “I go every Saturday to therapy,” she says. “Just because you see me on television doesn’t make those voices in my head go away.”

Her father died from liver cancer in 2006, and she talks about him with joy: “I was rambunctious. My dad nurtured it.” He would tell her that she’d win Oscars someday. “I was a creative thinker.” She points to her brain. “That muscle is strong. You give me a script? I will expound upon it. I will write an Academy Award-winning scene.”

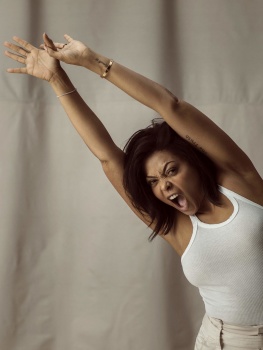

Today, she’s promoting her lead role in What Men Want, a remake of 2000’s Mel Gibson-helmed rom-com What Women Want. The film is told from the perspective of a female lothario in the workplace, a reaction to the #MeToo movement. “I was excited to be dealing with subject matter that’s going on right now,” she says. “We dig in. You’re laughing but it makes you think.” In Hollywood, Henson says men still get uncomfortable around powerful women. “I don’t know why. We’re only gonna make you look better,” she says. “My mouth is just as crass. You can’t crumble me with a sexist joke. If anything, I’m waiting for you to say something so I can check your ***.”

Henson talks like she’s always had her eyes on the bullseye. In school, she had two jobs. She worked part-time as a secretary at the Pentagon while, at night, she was a singing and dancing waitress on a dinner-cruise ship. Acting was always the focus and she continued to pursue that dream as a single mother to her now 24-year-old son, Marcel. His father – from whom she was separated – was murdered in 2003 by a couple after he confronted them about slashing his friend’s tires. Henson raised Marcel without father figures. “It’s hard,” she sighs. “I dreamed he would go stay with his dad in his teens, or my dad. I didn’t date. I wondered: Does he have enough confidence in himself as a black man? I wouldn’t wish being a single mother on my worst enemy. You need both parents.”

She took from the matriarchs in her family, her grandmother Patsy particularly. “She’s the reason my son never ate cereal,” she says. “He had a home-cooked breakfast every day. I could have a 5am call time but I would cook him eggs, pancakes, French toast… You can’t expect a child to learn on an empty stomach.” She’s most proud of his compassion for others. “He’s very sensitive. I love that I raised a man who’s not afraid to cry.”

Right now, she is balancing her workaholism with nuptials. On Mothers’ Day last year, at the age of 47, she got engaged to her former NFL-playing boyfriend Kelvin Hayden. She always wanted to get married. “I didn’t wanna settle. I just waited,” she says. Hayden proposed at the restaurant where they had their first date. She didn’t catch on until violinists appeared at the table playing their song. “His hand was all clammy,” she laughs. “Dude, you have been quizzing me for a year about getting married. Do you think I’m gonna say no?!” Clearly it was an offer that passed the Henson test.

What Men Want is out Feb 8 (US); March 22 (US)