Off Beat

[FONT=Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif]For years, he was the booze-soaked bard of the barstool, the keeper of 'a bad liver and a broken heart'. But Tom Waits was saved by his wife, hasn't had a drink for more than a decade and, at 56, is making the music of his life. [/FONT]

[FONT=Arial,Helvetica,sans-serif]

[/FONT]Interview by Sean O'Hagan

Sunday October 29, 2006

When Tom Waits was a boy, he heard the world differently. Sometimes, it sounded so out-of-kilter, it scared him. The rustle of a piece of paper could make him wince, the sound of his mother tucking him in at night might cause him to curl up as if in pain.

'It wasn't a cool thing,' he says, shaking his head lest there be any doubt. 'It was a frightening thing. I mean, I thought I was mentally ill, that maybe I was ********. I'd put my hand on a sheet like this [rubbing his shirt] and it'd sound like sandpaper. Or a plane going by.'

He is rocking back and forward on his seat as he recalls this and you can tell that traces of it still linger. 'I think I was having a spell,' he says, his creased, weather-beaten face crinkling even more. 'It would descend upon me at night when the house got quiet, and I'd say to myself, "Uh-oh, here they come again."' He rocks some more. They? I say, surprised. Did he think he was possessed?

'I really didn't know. Couldn't figure it out.'

Did he tell anyone? 'I think I told my mum. I'm not sure. See, I thought I'd outgrow it. Like acne. Or masturbation.' And he did eventually, though the thought of it still haunts him. 'I've read that other people, artistic people, have experienced it, too,' he says, still rocking. 'They've had periods where there was a distortion to the world that disturbed them.'

So, here we are, 50-odd years later, and Tom Waits has made a career out of distorting the world in an often disturbing way. His songs often sound like they have been bashed out of shape, put through a wringer, then left to dry in the sun until they are parched and somehow pure of spirit. On his new album, Orphans, which is really three albums in one, he grabs hold of a few songs belonging to other singers. Daniel Johnston's 'King Kong' becomes a bestial howl of despair, even more odd than the original. He scares the daylights out of the Disney standard 'Heigh Ho', from Snow White, turning it into what sounds like a slave song set to the pounding of an ogre's hammer. 'I like to go for that broken-down feel,' he says, 'the disintegration of it all.'

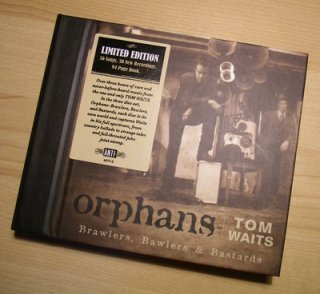

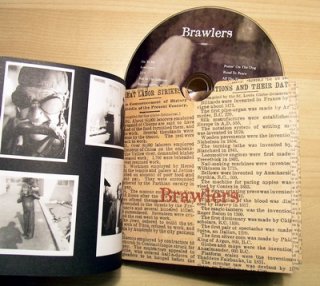

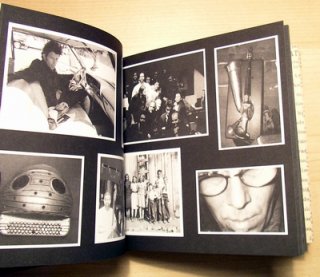

Orphans is a big, sprawling map of disintegration, a triple album containing 54 songs, 30 of which are brand new, while the rest have been gathered up from various one-off projects, film soundtracks and stage plays. His wife, Kathleen, once said there were two types of Tom Waits songs, 'the grim reapers and the grand weepers', but Orphans suggest there are at least three. 'Brawlers' is made up of blues stomps and raw rockers; 'Bawlers' is full of those beautiful, broken-down ballads of his that always sound oddly familiar, and 'Bastards' is a series of fits and starts, noisy outbursts that range from the cantankerous to the unhinged.

It's the first time in over 20 albums that Waits has divided his music along such generic lines. I figure that, at 56, he's finally mellowing out. 'Don't know 'bout that,' he says, sounding even more gruff than usual, maybe a little offended. 'Just thought it would make for easier listening if I put them in categories. It's a combination platter, rare and new. Some of it is only a few months old, and some of it is like the dough you have left over so you can make another pie.'

And one song stands out. Called 'Road to Peace', it concerns the Middle East conflict. It's not the kind of song he usually sings, though his last album also contained an anti-war song called 'The Day after Tomorrow'. This one is angrier. 'I was pissed off,' he sighs, rubbing his eyes. 'Started with a line I read in the paper one day: "He studied so hard it was as if he had a future." It was about this kid who got blown up in a suicide bomb on a bus in Israel. They say God doesn't give you anything he knows you can't handle. Well, I don't know if I believe that.'

He'll probably get his *** kicked, I say, for the line '... why are we arming the Israeli Army with guns and tanks and bullets?' He nods. 'Maybe. Maybe. But, we are. That's just a fact.

I guess any time anyone from outside a situation voices an opinion, it's going to be, "Who the f*ck are you?" Don't matter what side you're on. But this song ain't about taking sides, it's an indictment of both sides. I tried to be as equitable as possible.'

The places and the incidents referred to in the song are all real, and the names of the people, too. He's well aware, he says, of the risk of making a song carry that kind of weight. 'I don't really know what a song like that can achieve, but I was compelled to write it. I don't know if any genuine meaningful change could ever result from a song. It's kind of like throwing peanuts at a gorilla.'

Waits talks like he sings, in a rasping drawl and with an old-timer's wealth of received wisdom. It's as if, in late middle-age, he has grown into the person he always wanted to be. His tales are often tall, and his metaphors and similes tend towards the surreal. 'Writing songs is like capturing birds without killing them,' he quips. 'Sometimes you end up with nothing but a mouthful of feathers.'

We are sitting out the back of the Little Amsterdam oyster bar, half an hour's drive north of Petaluma, where they filmed Peggy Sue Got Married. It's the only diner with a windmill out front. Tom's kind of place: a slightly run-down Dutch diner where Mariachi bands used to play at weekends until the owner's entertainment licence was revoked after he got busted for having an illegal trailer park out the back. Tom's signed the petition like everybody else who passes through.

Outside, as far as the eye can see, there are gently rolling sun-burnished hills, tall trees, grazing cattle. It could be Tuscany except for the sign that says 'Open for Hamburgers'. This is Tom's home turf. He lives further on up the road somewhere, on a ranch deep in Napa Valley near Santa Rosa. These days, Waits does not stray far from home; the musicians come to him. His tours tend to be short, and not very often. 'Gotta keep 'em hungry,' he quips. 'You know what they say, "Don't feed the dolphins or they'll poke a hole in your boat next time you go out."'

Around the back of the Little Amsterdam, near the ancient rubbish bins and the furniture that has died from overuse, we are seated at a rickety table beside an old broken-down, rain-warped piano. Waits is drinking black coffee from a paper cup, wearing a suit at least one size too small, scuffed biker boots and a weather-beaten look that says, 'I've seen it all.' His hair is thinner now, but still has a mind of its own. His guitar is nestling in a case on the tarmac, on which rests a well-worn porkpie hat. He could have just stepped out of one of his own songs.

'Just look at this piano,' he says, the voice low and hoarse, and just the way you'd imagine it to be from his singing. 'Why has this piano been left out in the rain? It will never have a song pass through its chambers again. That's a sad thing, right?'

I look at the piano, discarded and battered beyond repair by the elements, and I nod. It is a sad thing. Sad enough to end up in a Tom Waits song. This is exactly the kind of place where the famously wayward piano in 'The Piano has been Drinking (Not Me)' might have ended up. Coincidentally, we've just been talking about drinking, and about losing your way in the fog that can sometimes settle on a life when a person loses track of where he is, who he is, and where the hell he was going.

Way back, when I first stumbled on Tom Waits while rooting though a friend's record collection, every song seemed to be about drinking and losing your way in the fog. His first record was even called 'Closing Time', but it sounded more like a lock-in at the loneliest bar in the world. Just Tom in the corner slumped over the piano serenading the last few nighthawks with his slurred songs about heartaches and hangovers, and the girl that got away.

His persona had already been perfected by the time he started living in the Tropicana Motel in Los Angeles in 1975, a faded establishment that also housed a couple of aristocratic junkies and several call girls who worked Sunset Strip. For six albums on Asylum Records, from his aforementioned debut in 1973 to 1980's Heartattack and Vine, Waits was the gravel-voiced, beer-stained bard of the barstool, a latter-day beatnik with a bad liver and a broken heart, whose fans were few and far between, but utterly devoted. And, boy, did he pay his dues.

'I opened for Frank Zappa, for John Prine, Martha and the Vandellas, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee,' he says now, sighing at the memory of those never-ending tours, the Godforsaken juke joints and the bounced cheques. 'I even opened for Buffalo Bob. Got to take it where you find it.'

Buffalo Bob, for the uninitiated, was a children's television star who made his name in the Fifties with an old-fashioned puppet show. 'Used to watch him when I was four years old,' laughs Waits. 'Now I'm opening for him in Atlanta. Every night he'd fill my piano with candy. Used to call me Tommy. I got him in a headlock one night, said, "You call me Tommy any more, I'll snap your head off."'

Back then, I saw Waits die a slow death in Ronnie Scott's, during a residency that nearly drove him over the edge. 'Supporting Monty Alexander,' he says, dryly. 'Got in a fight with Pete King [the promoter]. We didn't see eye to eye. I was young and naive. I was new to everything and far from home.'

For a long while, it looked like Waits would remain a cult figure, out on the furthermost horizon of the Seventies music scene, a stumblebum troubadour raised on bourbon and Bukowski. His music suggested and, to a lesser degree, still suggests, that the Sixties utterly passed him by; that, in his self-contained universe, the Beats were far more important than the Beatles, and Sinatra took precedence over the Stones.

'You imitate what you grow up around,' he says, when I mention this. 'If you grow up around Sinatra, Crosby and Louis Armstrong as a kid, it goes in and stays in. But some of that Sixties stuff went in too.'

guardian.co.uk

thanks missmag...i feel so bad i only own I'm your man out of that list. but it still encourages me to get the rest sooner or later.

thanks missmag...i feel so bad i only own I'm your man out of that list. but it still encourages me to get the rest sooner or later.

Overspill~Nine More Albums from the guardian.co.uk blog.

Overspill~Nine More Albums from the guardian.co.uk blog.  ...I counted & The Pub lied...

...I counted & The Pub lied... ...there are only eight...

...there are only eight...

i eat my last comment: the album is up on soulseek.

i eat my last comment: the album is up on soulseek.