-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Viola Davis

- Thread starter sobriquet87

- Start date

Not Plain Jane

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2010

- Messages

- 15,480

- Reaction score

- 846

what a stunner; loved her hair and jewels

HeatherAnne

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 24,230

- Reaction score

- 994

Suchhh a good color choice, she and Saoirse best dressed in different shades of pink, hands down.

Nymphaea

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 30, 2012

- Messages

- 6,196

- Reaction score

- 695

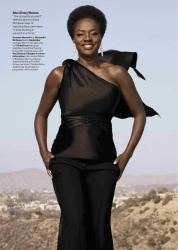

Interview Porter Edit

netaporterWhen an actress is as straight-talking, insightful and impassioned as VIOLA DAVIS, nothing is out of bounds – as she puts it, authenticity is her rebellion. AJESH PATALAY hears from one of TV’s most candid stars about sexual liberation, the value of women of color, and her #MeToo experiences.

There is no shortage of women raising their voices against abuse and injustice right now. But what a woman, and what a voice, is Viola Davis. On January 20, the Oscar-winning actress took to the stage at the Women’s March in LA to speak about r*pe and trafficking, and how no change is great unless it costs us something. She did the equivalent with words of reaching into our chests and tearing at our heartstrings.

And not for the first time, either. On winning an Emmy in 2015 for her role as law professor Annalise Keating in ABC’s hit series How to Get Away with Murder (the first African American ever to win in the Lead Actress category), Davis didn’t squander the moment with thank yous. Instead, she talked about the lack of opportunity for women of color, quoting her heroine Harriet Tubman, and delivered one of the most rousing speeches of the year: “The only thing that separates women of color from anyone else is opportunity. You cannot win an Emmy for roles that are simply not there. So here’s to all the writers, the awesome people that are Ben Sherwood, Paul Lee, Peter Nowalk, Shonda Rhimes – people who have redefined what it means to be beautiful, to be sexy, to be a leading woman, to be black.”

One newspaper called it “a masterclass in delivery”. But they might as well have called it a masterclass in one woman knowing exactly how she feels and not being afraid to say it. Which is how I find her, sitting on a sofa in a house in the Hollywood Hills, talking frankly about everything you’d want her to set the record straight about: #MeToo; ‘Time’s Up’; the gender pay gap; #OscarsSoWhite; and, well, the How to Get Away with Murder/Scandal crossover episode, which brings together the characters of Olivia Pope (played by Kerry Washington) and Keating for the first time ever. “I don’t know how else to describe it,” Davis says, beaming. “It felt like we were creating history. I mean, to have two really strong, well-written, well-rounded characters in the same room together, who are women of color? It’s black-girl magic at its best.”

Davis knows all too well that roles like Annalise Keating don’t come along often, “especially for a woman who looks like me,” she says. “I’m 52 and darker than a paper bag. Women who look like me are relegated to the back of the bus, auditioning for crackheads and mammas and the person with a hand on her hip who is always described as ‘sassy’ or ‘soulful’. I’ve had a 30-year career and I have rarely gotten roles that are fleshed out, even a little bit. I mean, you wouldn’t think [these characters] have a vagina. Annalise Keating has changed the game. I don’t even care if she doesn’t make sense. I love that she’s unrestricted, that every week I actually have to fight [showrunner] Peter Nowalk not to have another love scene. When does that ever happen?”

Has playing voracious Annalise changed the way she sees herself sexually? “Yes, and it’s been a painful journey,” she says, laughing, presumably because these sex scenes often take place across desks and up against walls. “It costs me something,” she continues, more earnestly, “because very rarely in my career – and in my life – have I been allowed to explore that part of myself, to be given permission to know that is an aspect of my humanity, that I desire and am desired. I always felt in playing sexuality you have to look a certain way, to be a certain size, to walk a certain way. Until I realized that what makes people lean in is when they see themselves. There’s no way I am going to believe that all women who are sexualized are size zero or two, all have straight hair, all look like sex kittens every time they go to bed and want sex from their man, all are heterosexual. I am mirroring women. I always say it is not my job to be sexy, it’s my job to be sexual. That’s the difference.”

She breaks off: “That’s my daughter, by the way.” And there, standing behind me, is a pretty girl in a blue dress. “Say hi, Gigi! I’m doing an interview.” Mother and daughter blow kisses to each other across the room, and then the six-year-old, whose name is actually Genesis, scoots off with her nanny. It’s a side to Davis I’d like to see more of, the doting mother. I’d also like to see more of the off-duty side; the Davis who throws barbecues and drinks tequila and likes hot-tubbing with her actor-producer husband, Julius Tennon. “I’m actually fun,” she cries at one point, as if to free herself from all this serious talk. But we both know she has a lot more to say, including about race.

This Sunday, Davis will be attending the Oscars, after winning Best Supporting Actress last year for her role in Fences. But when I ask about the several nominations awarded to non-white artists this year, following 2017’s #OscarsSoWhite campaign, she isn’t impressed. “Here’s the thing: it’s not about the Oscars,” she starts, “it’s about how we’re included in every aspect of the movie-making business. When you look at a role as a director or producer that is not ethnically specific, can you consider an actor of color, to invest in that talent? The problem is, if it’s not an urban or civil rights drama, they don’t see you in the story. People need to understand that they shouldn’t see people of color one way. We don’t always have to be slaves or in the ’hood or fighting the KKK. I could be in a romantic comedy. I could be in Gone Girl. Or Wild. I could be seen the same way as Nicole Kidman, Meryl Streep, Julianne Moore. I actually came from the same sort of background; I went to Juilliard, I’ve done Broadway. I’ve worked with the Steven Spielbergs. I should be seen the same way. That’s what I think is missing: imagination.”

There’s also the issue of pay, “especially for actresses of color,” she says. “If Caucasian women are getting 50% of what men are getting paid, we’re not even getting a quarter of what white women are getting paid. We don’t even get the magazine covers white women get. And that is not speaking in a way that is angry,” she adds. “They deserve everything they get paid. Nicole Kidman deserves it. Reese Witherspoon deserves it. Meryl Streep, Julianne Moore, Frances McDormand… But guess what – I deserve it too. So does Octavia Spencer, Taraji P. Henson, Halle Berry. We’ve put the work in too.”

Does she think white actresses have a part to play in changing that? “I don’t want to tell anyone what to do,” she says, “but I think Jessica Chastain did a really boss move with Octavia Spencer [on their latest, as yet untitled project] by saying Octavia’s got to be paid the same as her. She actually upped Octavia’s quote for that movie because she took a salary cut. I think Caucasian women have to stand in solidarity with us. And they have to understand we are not in the same boat. Even a lot of female-driven events in Hollywood, like power luncheons – which I’ve been to, and are awesome by the way – there will be 3,000 women in that room and five of them are women of color. And it’s by invite! So, you’re not even inviting us.”

You can see why Davis is the perfect champion for this moment – she is unapologetic to her core. “Every time I do an interview,” she says, “I am always quick to say, I say it out of love but I got to speak my truth. If I don’t, it’s like a friggin’ cyst that hasn’t been popped. I don’t want to come off sounding bitter, because I’m not. I’m actually quite joyful in my life; my life could not have played out any better. But my authenticity is my rebellion.”

Jane Fonda, of all people, once praised Davis for having presence. And it’s no exaggeration to say that, for much of our conversation, I feel goosebumps hearing her speak, particularly when talk turns to #MeToo. When I ask if she thinks the movement would have gained traction if the women who first came forward had been women of color, she cuts me off even before I’ve finished – “No,” she says. “No. Recy Taylor came forward in 1944 when she was gang raped by six men in Alabama. Tarana Burke was the founder of the #MeToo movement in 2006. There are plenty of black women who have come forward. I don’t think people feel we deserve the same empathy. Or investment. We are not as valued. If the story wasn’t coming out of Hollywood, and the predator wasn’t someone like [Harvey] Weinstein, I don’t think it would have gotten the spotlight [either].”

But why, in her view, have these allegations surfaced now? “Fannie Lou Hamer, the ’60s civil rights activist, has a saying: ‘I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.’ I think that sums it up. All the women I have known and had private conversations with have been sexually assaulted on some level. But we talk in private. I think after a while you hit a wall, and then it becomes a no-brainer. You have to speak up in the midst of no one speaking up for you.”

Davis has talked unspecifically about her own #MeToo story and I ask if she will ever share it. “Oh no, not only do I have my own story, I have my own stories. I am telling you, I have had men touch me in inappropriate ways throughout my childhood,” she says. “I have had men follow me on any given day – and I am saying during the day, at one o’clock in the afternoon – and expose themselves to me. I remember one day, when I was 27, waiting at the bus stop in Rhode Island for my niece to get out of pre-school. I was probably there 25 minutes, and I am not lying because I counted, 26 cars drove by with men in them who solicited me, harassed me, yelled at me, verbally abused me. Some of these men had baby seats in the back. And yeah, it makes you feel like crap, it makes you feel like, what would a childhood be if that were removed? And it’s hard to separate that stain from who you are. You tattoo it on yourself. Those personal experiences have allowed me to feel compassion for the women who have spoken up.”

Inevitably, we get talking about the #MeToo backlash, and the women who have publicly criticized the movement, who Davis thinks are missing the point. “Hollywood is a microcosm,” she says, “and however you feel about the movement, it has given women permission to talk about their sexual assault and be a community with each other.” She slaps her hands together. “Community, that’s a good word. I know it’s a ‘kumbaya’ word, but you know what, the minute you feel isolated and you’re on your own, is the minute you’re dead.”

She tells a story of being sat next to a life coach at a party. “He kept saying, ‘Viola, a lot of people feel disillusioned once they get everything they want, because everybody fights for success, they get there and realize they forgot the next goal. And the next goal is significance.’ That is what I would say to women who are denouncing the ‘Time’s Up’ movement: what is your significance? What do you want to leave the world? If you ever have a daughter or niece or young girl who looks up to you, who wants to say, ‘You know what, I remember when I was three and sexually assaulted…’ You can either choose significance, or you can choose that soundbite that took two minutes to give a Twitter feed.”

She goes on. “I always say life is like a baton and you got to run your leg of the race and pass it on to the next great runner. I want to pass a fabulous baton and leave something that makes me immortal, in a fabulous way. I want to leave an elixir that people can taste and that makes them feel alive.”

All I can think is, me too.

Watch How to Get Away with Murder on ABC now

HeatherAnne

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 24,230

- Reaction score

- 994

What a breathtaking spread, she looks stunning

Not Plain Jane

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2010

- Messages

- 15,480

- Reaction score

- 846

she looks so different with her hair like this!

Yohji

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 12, 2015

- Messages

- 11,344

- Reaction score

- 3,433

^Oh dear...

Actress Viola Davis visits "The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon" at Rockefeller Center on November 13, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends the 2018 Glamour Women Of The Year Awards: Women Rise on November 12, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends "Widows" New York Special Screening at Brooklyn Academy of Music on November 11, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends the 2018 British Academy Britannia Awards presented by Jaguar Land Rover and American Airlines at The Beverly Hilton Hotel on October 26, 2018 in Beverly Hills, California.

Viola Davis attends the European Premiere of "Widows" and opening night gala of the 62nd BFI London Film Festival on October 10, 2018 in London, England.

Viola Davis is seen at 'Jimmy kimmel Live' in Los Angeles, California.

Viola Davis attends the "Widows" press conference during 2018 Toronto International Film Festival at TIFF Bell Lightbox on September 9, 2018 in Toronto, Canada.

Viola Davis attends the "Widows" premiere during 2018 Toronto International Film Festival at Roy Thomson Hall on September 8, 2018 in Toronto, Canada.

Actor Viola Davis attends "The Last Defense" during the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival at SVA Theatre on April 27, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends Variety's Power of Women: New York at Cipriani Wall Street on April 13, 2018 in New York City.

zimbio.com

Viola Davis attends the 2018 Glamour Women Of The Year Awards: Women Rise on November 12, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends "Widows" New York Special Screening at Brooklyn Academy of Music on November 11, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends the 2018 British Academy Britannia Awards presented by Jaguar Land Rover and American Airlines at The Beverly Hilton Hotel on October 26, 2018 in Beverly Hills, California.

Viola Davis attends the European Premiere of "Widows" and opening night gala of the 62nd BFI London Film Festival on October 10, 2018 in London, England.

Viola Davis is seen at 'Jimmy kimmel Live' in Los Angeles, California.

Viola Davis attends the "Widows" press conference during 2018 Toronto International Film Festival at TIFF Bell Lightbox on September 9, 2018 in Toronto, Canada.

Viola Davis attends the "Widows" premiere during 2018 Toronto International Film Festival at Roy Thomson Hall on September 8, 2018 in Toronto, Canada.

Actor Viola Davis attends "The Last Defense" during the 2018 Tribeca Film Festival at SVA Theatre on April 27, 2018 in New York City.

Viola Davis attends Variety's Power of Women: New York at Cipriani Wall Street on April 13, 2018 in New York City.

zimbio.com

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)