You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

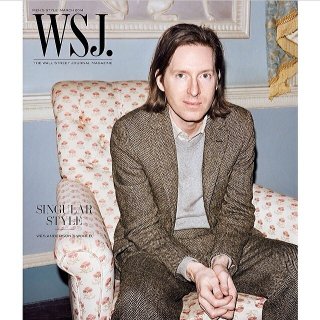

WSJ Magazine Men's Style March 2014 : Wes Anderson by Angelo Pennetta

- Thread starter Flashbang

- Start date

mistress_f

Hell on Heels

- Joined

- May 27, 2007

- Messages

- 7,239

- Reaction score

- 361

this has the potential to be interesting, even though wes is looking more awkward than usual, bless him

Thefrenchy

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Nov 13, 2006

- Messages

- 11,802

- Reaction score

- 659

Saw The Grand Budapest Hotel this morning, I love him. Great cover.

JuiceMajor

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 8, 2005

- Messages

- 4,509

- Reaction score

- 1

Any editorials? Nice cover!

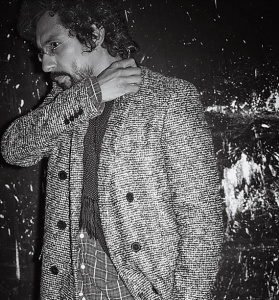

Ph: Ezra Petronio

wsj.comIT IS NOON ON SUNDAY in early January, and Haider Ackermann alternates between sipping coffee and Perrier in the library of the understated Pavillon de la Reine hotel in Place des Vosges—one of his favorite haunts in Paris, where he puts up his parents when they visit. The designer's studio, around the corner from the hotel, is more of a creative pied-à-terre think tank than his Antwerp headquarters. "In Paris, I'm on my own with my assistant," he says. "We talk about what I want to do and start drawing. Here is the cocoon. Then we go to Antwerp, and I translate my work to the team and make it real." He spends half the week in France and the other half in Belgium.

Ackermann is 42, with thick, curly black hair pomaded back, and tiny wire spectacles just covering his eyes. He wears a loose, blue plaid shirt and a silk polka-dotted scarf jauntily knotted around his neck. The look is rounded out with purple socks, pointy black shoes and drop-crotch gray trousers with green side-stripes (the pants are his own design). On one thumbnail is a smattering of chipped teal polish; the other is black. The outfit may sound extreme—grunge–meets–pirate–meets–marching band drummer—but he pulls it off. In fact, this free-for-all hopscotch through aesthetics is the foundation of his fashion, a mini empire that is expanding with last year's introduction of menswear.

Although the once-underground it-designer has evolved into a major fashion player—his clothes have become red-carpet staples of cerebral fashion-forward stars like Tilda Swinton —will he continue his slow-burn momentum to become a full-scale multi-category international brand?

"I don't think I'm searching for success," he says. He's had no problem stumbling into it, but he admits there's more at stake this go-round. "I'm more nervous," he says of his sophomore men's collection, which he'd show the following week. "The first time there was a sense of freedom—you just do it. Now we have shops, it needs to sell. It's more concrete."

Ackermann made a brief foray into men's clothes in 2010, by presenting looks (as a special guest women's designer) at Pitti Uomo, a trade show in Florence. It was a barrage of dizzying prints and silky pajama-like pants. "They gave me a budget, and I could do whatever I wanted," he says. "I wondered, Who is the man behind the Ackermann woman? And then I let it go because I was not ready."

A full collection didn't appear until spring 2014. Now in stores, it blends vagabond Byronesque romance with Rebel Without a Cause swagger and gypsy wanderlust. The palette includes fuchsia and mauve, and he doesn't skimp on silk. It was an across-the-board critical hit, even with American men's magazines that often shy away from more outré European designers. It also impressed retail fashion directors. It is being sold in 20 countries, including Barneys and Saks in the U.S. "He's an artist like a painter or a sculptor," says Tom Kalendarian, the executive vice president for menswear at Barneys. "He will only do what he wants to and loves."

The collection isn't the most practical, but that's not, nor ever is, Ackermann's point. His flair for dressing women has translated to men is even more out there. "His menswear takes bohemian dressing to another level," Kalendarian says. "You don't necessarily identify his clothes with a brand as much as with the person who wears them—a man who looks unique and artistic. There is a mood of romanticism—sometimes his pieces look like a dressing gown or a smoking jacket. They conjure an image of someone sensual and mysterious."

The photographer and artist Katerina Jebb, a friend, has been documenting Ackermann's shows since the beginning. "Haider has a good relationship with his inner world," Jebb says. "It's a motive for what he makes. He allows himself to leave rationality. It's not 'what do we need: trousers, a sweater and a pair of sneakers?' He goes beyond necessity, which is what true luxury is. Who needs a silk peignoir? You don't need anything made of silk or velvet, but you dream about it. He's cultivating people's dreams."

ACKERMANN'S fashion-without-borders approach corresponds to his globe-trotting upbringing. Born in Colombia, he was adopted by French parents as an infant. "My sister and brother are Asian," he says. "We had to fight to make people believe we were a family." His neighborhood in Paris, Ménilmontant in the 20th arrondissement, is similarly multiethnic.

His father was a cartographer, and the family lived in Africa during Ackermann's childhood—Ethiopia, Chad and Algeria. "I have beautiful memories," he says. "But of course it was an unstable life. Even today, if I'm too much in one place I want to move and go on the road again." His wanderings affect his work subliminally. "Even in India," he says, "I never take pictures. I absorb things and try to remember them. If they stay in my mind, then it's meant to be."

In Africa, he studied ballet and dreamed of becoming a dancer. When he was 11, his family relocated to a small Dutch town, where his passion for dance waned. "In Africa, we were dancing in a T-shirt and bare feet," he says. "I went to Holland, and there were all of these girls with blonde hair and tutus. I didn't speak the language and was the only dark-skinned person and the only boy."

He learned Dutch (he also speaks French, German and English) but felt like an outsider. "I was silent," he says. "I wasn't the person I wanted to be. We lived in a bourgeois area. I tried to be like the others and wasn't myself. It was difficult to come to school in Holland with my skin color. I was always dreaming of escape."

As his interest in fashion developed, he saw that it was a means for both assimilating and for standing out. At 17, he moved to Amsterdam on his own. "I was still shy," he says. "I discovered nightlife and everything around it. I'd go to the wildest party without drinking or drugs, just observing."

At 22, he enrolled in fashion school at Antwerp's Royal Academy of Fine Arts. "I was not the most disciplined student," he admits. "In Africa, we were free, and there was wildness about it. In Holland and Antwerp, you had to follow what the teacher said. This was strange. I only wanted to go to school if I had something to say. If we had to do 10 silhouettes, I would do five." He was asked to leave without graduating.

"Suddenly all your dreams are not coming true," he says. "I thought I'd never make it. How can an insecure introvert make a career after being kicked out of school?" Ackermann stayed in Antwerp and worked at various discotheques. "It didn't mean I wasn't drawing every day," he says of the period. "I was dreaming, fantasizing, wishing and hoping. Every day I was thinking about my work." He credits his tight-knit circle of friends with pushing him to make his debut collection.

"I had a huge lack of confidence," he says. "My friends pushed me into throwing myself into the troubled waters. My mother told me the only thing you can lose is money, but you will regret never trying." He funded this venture himself with savings from working in clubs.

With his debut show in Paris, in 2002, he became an indie outsider on the fashion calendar. One could use words like fluid, liquid and undulating to describe Ackermann's abstract and lyrical oeuvre. "My work is built on emotions," he says. "It's complicated to talk about it. I find it difficult myself." His debut was picked up by Barneys and Colette. It also begot a lucrative gig designing for leather house Ruffo.

In 2005, his label was acquired by the Belgian investment group BVBA 32, whose chief executive is Anne Chapelle (their other fashion holding was Ann Demeulemeester ). "I'm an investor of not only money but of my time and energy," says Chapelle. "Haider has a personality I believed in." Even so, she thought the company desperately needed infrastructure. "I started with point zero with Haider. Together, we built it stone by stone."

The merger allowed Ackermann to follow his muse. "It gave me a sense of freedom," he says. "Before, I was packing boxes by myself. Now I could concentrate on my work." In June 2013, the fashion label separated from BVBA 32 to become an independent company, Atelier Haider Ackermann (Chapelle is the CEO). The women's line is now sold in 35 countries at more than 180 outlets.

....

wsj.comWHEN WE MEET, Ackermann has just returned from Los Angeles. "I was escaping," he says. "It was the first time I really spent time there. I was in Laurel Canyon for six days in a house in the hills with a garden."

Upon his return, he began preparing the fall men's presentation. None of the models at the pre-casting fit the bill. It made him long for California. "You see these characters—men walking around with their own style," he says of his West Coast trip. "I was so inspired. Then I came to Paris and just saw beautiful boys. I was lost. The clothes have to live to tell a story. If you just do beautiful clothes on beautiful boys it fades away." Ackermann seeks something for the eye to latch onto, a resonating fault. "I like the failure in a man," he says. "You need a distance, something unreachable and broken."

Ackermann's fall 2014 men's presentation was in a chilly vacant Marais space on January 15—a sober collection of tweed, herringbone and gray flannel—but in his hands the result was hardly staid. The overcoats were long and sumptuous, more akin to a king's cloak than a mac. Some baggy silk and cotton jacquard pants featured an intricate print of abstract geometrics suitable for a mosque wall. Like all Ackermann shows, it was difficult to describe—mystic, swashbuckling businessmen explorers?

Taking such traditional materials and transforming them could be seen as subversive, with great crossover appeal, but those terms are too crass in describing Ackermann. "The decadence and extravagance of last time came from all the silks," he says. "This time, I wanted it to come from the inside. It was more subtle. I was thinking of Detroit and Chicago in the '40s. There is also something very deadly about it."

Akin to his personal style, there were scarves galore, of which he has a philosophy. "I don't feel naked with one," he says. "It sounds weird, but I feel more protected."

The next day, Ackermann will catch an early train for the weekly two-hour journey to Antwerp. "I like to read all the gossip magazines," he says. "I love trash. People are surprised that I can be light. They think I'm this heavy person. There is a dark cloud in there, but at midnight I will be dancing on a table. That's my Colombian side, and there is no tomorrow."

wsj.comThe Life Aesthetic With Wes Anderson

With the release of his eighth feature film, "The Grand Budapest Hotel," Wes Anderson takes another imaginative leap into a world of his own invention

GUESTS CAME BY funicular, ascending into the foothills above the fictional European spa town of Nebelsbad in the imagined nation of Zubrowka. They were greeted—the rich, the old, the insecure; the vain, the entitled and the needy—at the Grand Budapest Hotel by its heroic, mustachioed concierge, Gustave H, dressed in a purple tailcoat, perpetually perfumed with L'Air de Panache. Inside, the floors were covered with custom Art Nouveau carpets. Vaulted staircases led up toward magnificent panels of stained glass. H instructed his staff to keep the hotel "spotless and glorified." He deemed it "a great and noble house," before having his porters and waiters consider 46 stanzas of didactic, romantic poetry.

This is hospitality Wes Anderson –style and it took almost a decade to configure. The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson's eighth feature, out this month, began as a character sketch about a longtime friend. "The main thing," says Anderson by phone from London's Home House—not exactly a hotel but, rather, a private club with bedrooms upstairs and the director's base for a press day in Marylebone—"is he knows everything. And he's good with people. My friend is not a concierge, but would have been the greatest concierge had he fallen into it—and if he'd been born about a century earlier. I don't think concierges do quite the same things as they used to."

What they used to do—and, more importantly, what they've never done—is central to Grand Budapest, the entry point into yet another of Anderson's fully formed, meticulously researched and wholly original worlds. With each new film, Anderson, now 44, has honed a visual language all his own, refining his signature aesthetic in a way that enriches the emotional lives of his characters. To be sure, there's repetition across Anderson's cinematic landscape—of behavior and design—but the result is a richness few other filmmakers have consistently delivered. From 1996's Bottle Rocket, written with University of Texas classmate Owen Wilson in their Austin apartment (Anderson grew up in Houston), to 1998's Rushmore; from 2001's The Royal Tenenbaums to 2004's The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou; from 2007's The Darjeeling Limited to 2012's luminous Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson's worlds now form their own galaxy.

Obsessively curious—compensating, perhaps, for not living in the gilded era of Gustave H himself, between the World Wars—Anderson acquired as much knowledge as possible about his concierge's world before he got to work designing it. Prompted by postcard-like photographs he found in the Library of Congress's Photochrom Print Collection, he set off for Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany. "Before we went looking at all these old hotels, we looked at thousands of pictures—landscapes and cityscapes," says Anderson. "It was like having Google Earth for the Austro-Hungarian Empire." When Anderson's own Grand Budapest Hotel needed a pastry program, he turned to inspiration from the legendary Viennese bakery Demel. "They have sachertorte, and a friend told us it would always be Billy Wilder's first stop in Vienna. You have to respect pastry from this era, so I thought we should do a Demel for our own little made-up country."

Cake aside, Anderson was having trouble finding a structure that would properly house his own Grand Budapest until he arrived in the Saxon town of Görlitz and discovered the vacated Görlitzer Warenhaus department store. Constructed in 1912, the building appealed to Anderson for both its sizable atrium (it would become his hotel's lobby) and its ability to house his production offices, art department and workshop (bottles of L'Air de Panache and other objects had to be made) all under one roof. "I don't like things that remind me too much of traditional movie sets, where everyone's always getting in and out of vans," says Anderson.

"Wes works hard at creating an atmosphere of closeness," says Ralph Fiennes, a newcomer to the director's ensemble (regulars include Bill Murray, Jason Schwartzman and Wilson, all of whom appear in the film) and the man who breathes comedy and gravitas into Gustave H. "There are no trailers for individual actors," says Fiennes. "We all live in the same hotel, eat dinner together every night, get in costume in our rooms and just go downstairs for hair and makeup."

Though Anderson's movies often highlight the dysfunction of families, his sets celebrate their intimacy. Anderson likes to point out that his cinematic tribe isn't exclusively made up of actors. He's worked with illustrator Hugo Guinness, who has a story credit on Grand Budapest, since 2001. Cinematographer Robert Yeoman has been Anderson's director of photography since Bottle Rocket, almost 20 years ago. Fiennes, for his part, says he'd love to join the troupe again in the future. "Wes has an almost old-world way of considering other people," he says, "a rare kind of courtesy. But he's also very prepared, very specific." Case in point: those vans, which remained absent from the film location. "We got a bunch of Danish golf carts to drive around town in," says Anderson. "That's how we did most of our traveling."

There's more to Grand Budapest than reservations and room service. A comedy of manners with an adventurer's heart, the film finds its protagonist accused of murder, stripped of his post, imprisoned, escaped and riding cable cars high into an Alpine monastery in search of answers. (And, typically for this director, it's all very stylish, with costuming that achieves what Matt Zoller Seitz, critic and author of The Wes Anderson Collection, calls "material synecdoche," where "objects, locations or articles of clothing define whole personalities, relationships or conflicts.") It's perhaps the nearest thing to a Wes Anderson action blockbuster—a caper with both suspense and speed—though the director bristles at the description. "It's more us trying to do a Lubitsch-esque type of thing and maybe a '30s type of Hitchcock movie," he muses. "The cable car stuff, especially, was me trying to think of a scene that might have been a Hitchcock scene that never happened."

Anderson could cite references all day, footnoting his cinematic vision endlessly. There's no pithy response to questions regarding aesthetics. He'd never say he's going for neo-baroque with undertones of Americana. Instead, a painting made expressly for the movie—by the fictional Johannes Van Hoytl The Younger, and in real life by the artist Michael Taylor—triggers a riff on Old Masters. "Our reference was kind of Flemish painters. And Hans Holbein; I don't know if it's the younger or the elder. I like Brueghel, and another one that's maybe connected to this is a Bronzino at the Frick. We were trying to suggest that it wasn't an Italian Renaissance painting. That it was more northern." And then there's the matter of another early inspiration for the script, the work of the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig (1881–1942), whose temperament calls out to both Gustave H's fictional life and to Anderson's actual one.

Like H, Zweig was both a grandiloquent dandy and a moralist force. He owned Beethoven's writing desk, hung out with Rilke in Paris and even looked a little like Fiennes's character. ("The mustache and the big nose," says the actor. "I suppose that's right.") Like Anderson, Zweig mourned the end of a certain European era (titles, thermal baths) in his autobiography, The World of Yesterday, which would be an apt subtitle for Grand Budapest. "Wes has his own unusual nostalgia for a world he was never part of but would like to be," says Fiennes. He also has the kind of wanderlust exhibited by Zweig, who regularly found himself far from home in Zurich, Calcutta, London and Moscow.

The invented world of Wes Anderson depends very much on travel and real immersion (The director and his longtime girlfriend, the writer Juman Malouf, call New York home, though Anderson also owns an apartment in Paris and will gladly stay on set abroad for long stretches. "I never actually know how long I'm there for," he says, "time just becomes meaningless to me in that situation.") Anderson shot The Darjeeling Limited on a moving train in India. The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou features scenes filmed on a World War II–era minesweeper off the Italian coast. And Grand Budapest could not be completed without footage from inside a fin de siècle bathhouse (amazingly, one was discovered in Görlitz during production).

"I tend to want to make a movie some place because I want to know about that place," says Anderson, before hanging up to watch a final print prior to submitting Grand Budapest to the Berlin International Film Festival. "There's something to do with the characters and with the story, but there's something that has to do with the world they live in.

"I'm not quite sure where the next one will be," he says. "I will say I'm interested in Japan."

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 5

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 2K

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 3K

- Replies

- 37

- Views

- 9K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)