You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

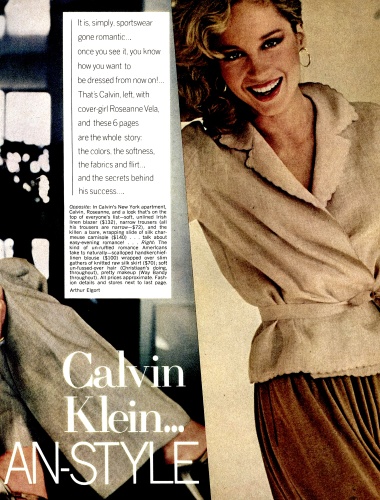

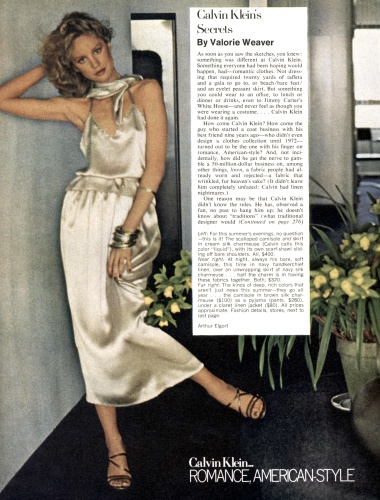

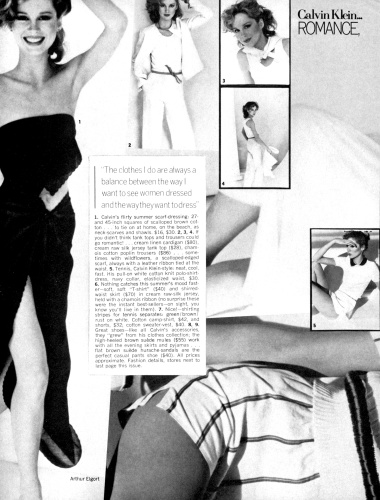

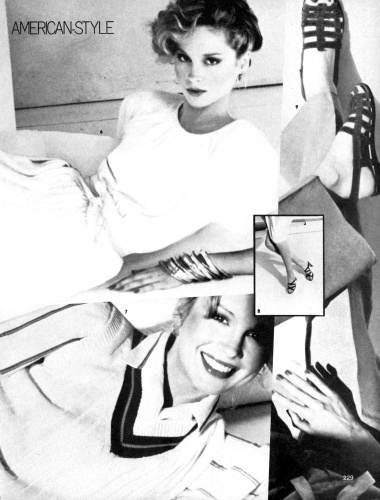

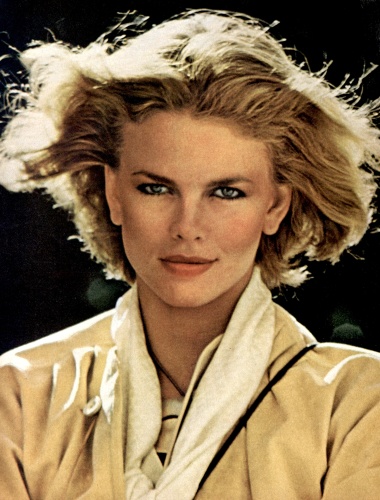

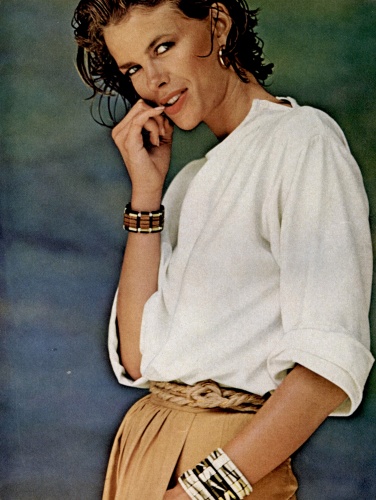

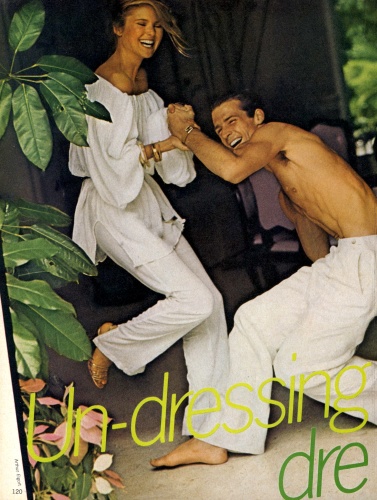

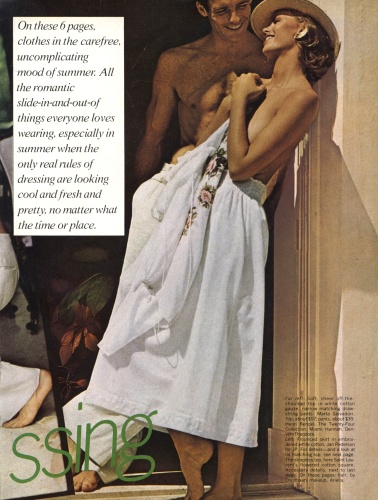

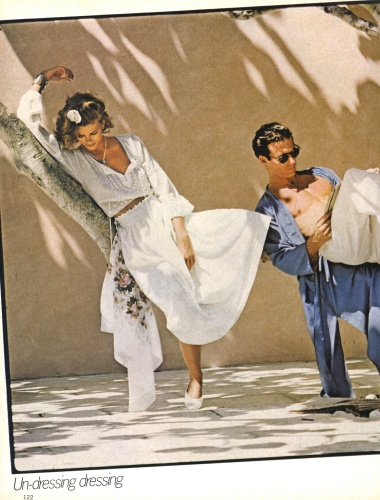

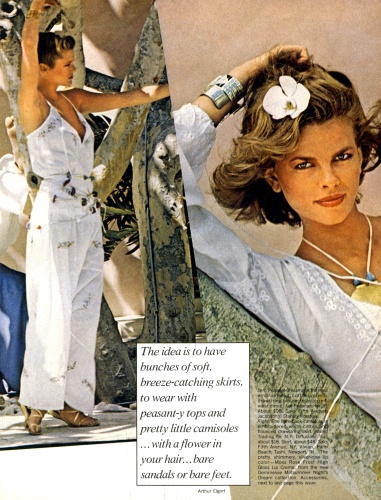

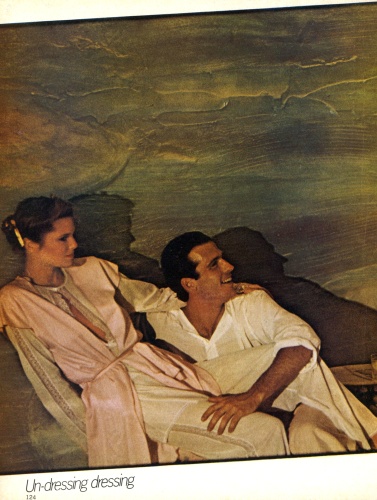

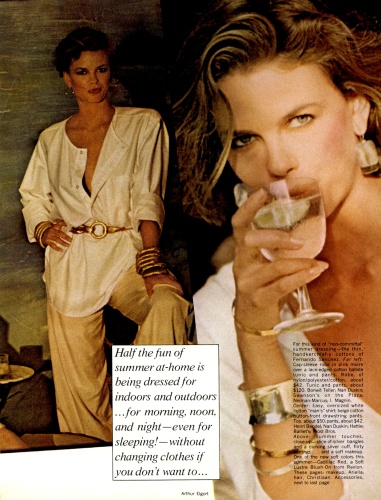

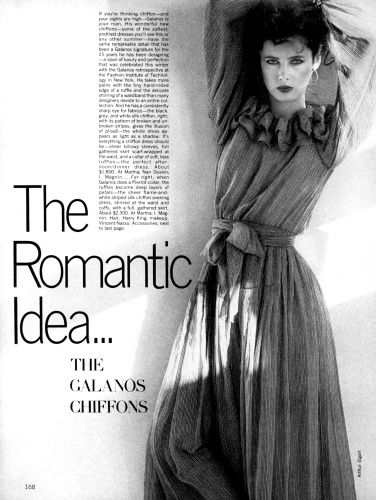

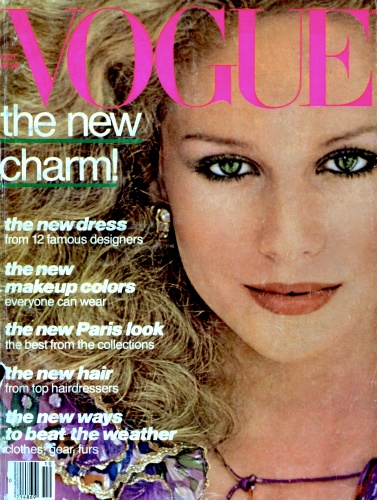

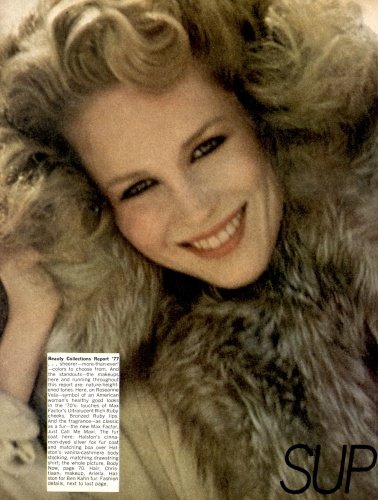

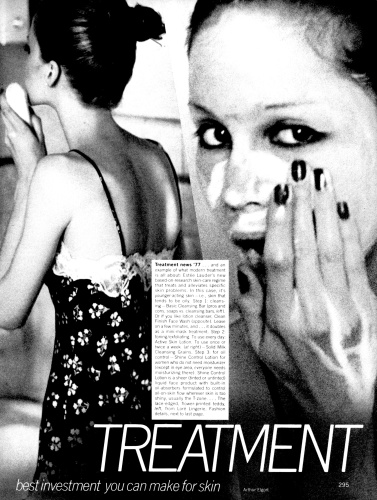

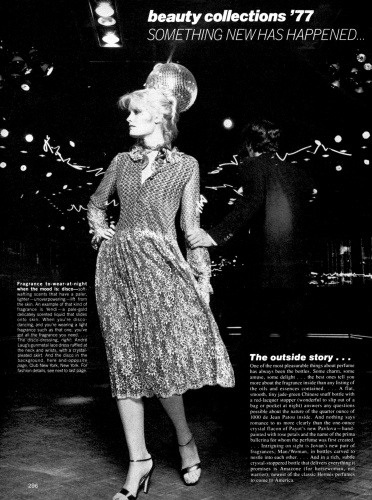

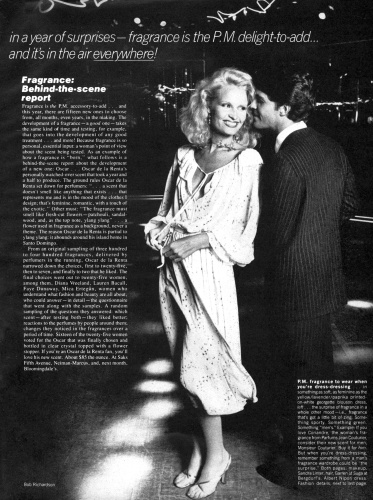

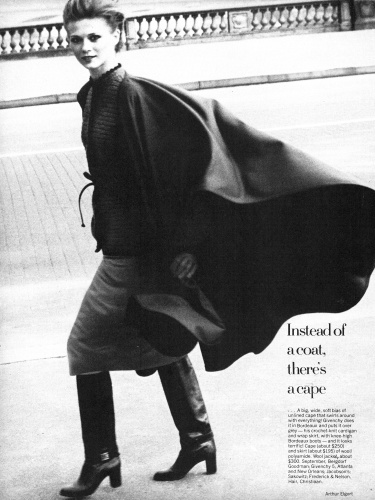

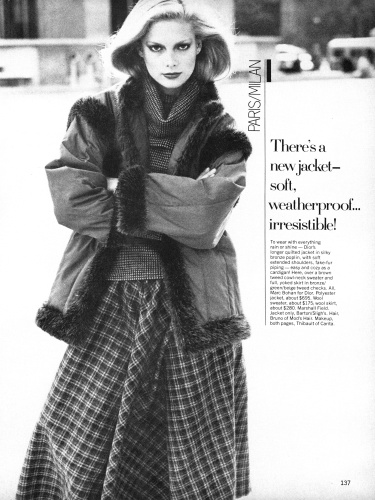

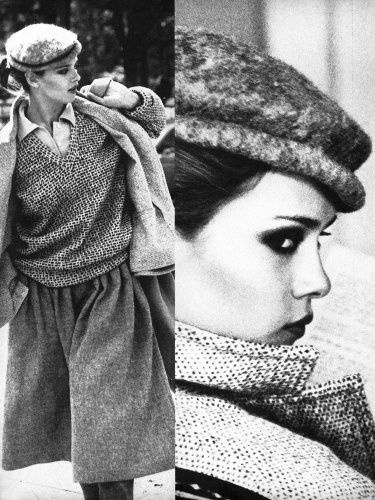

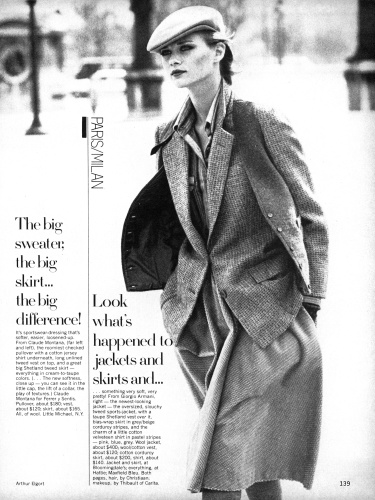

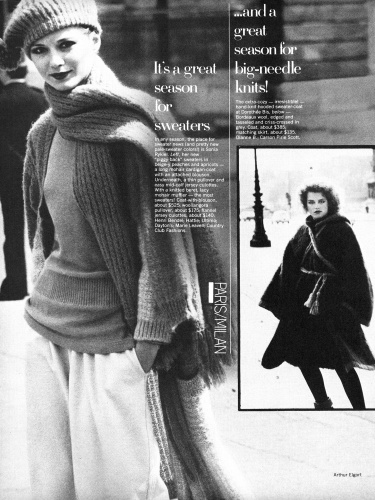

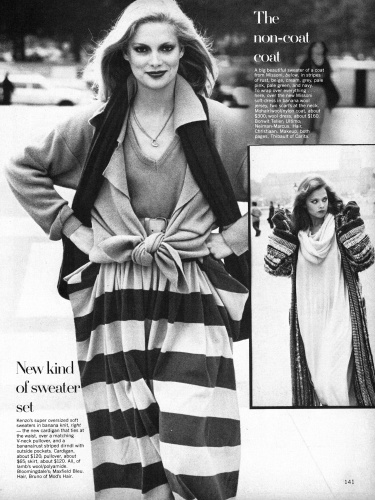

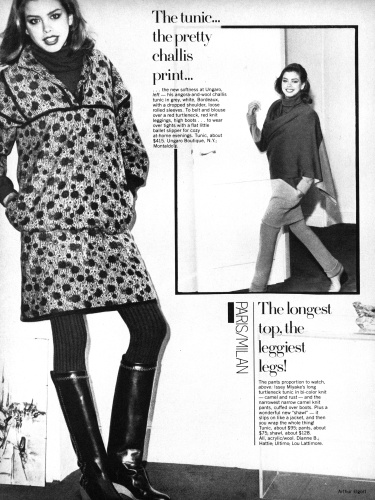

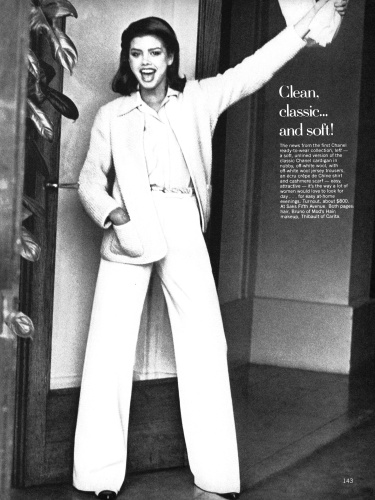

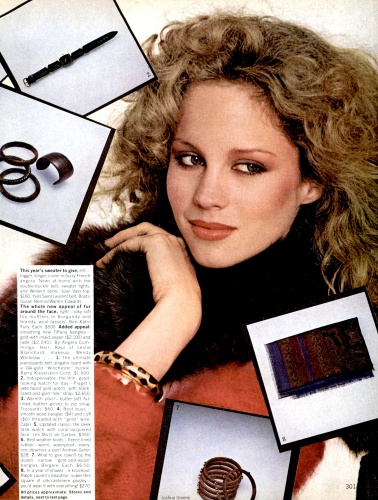

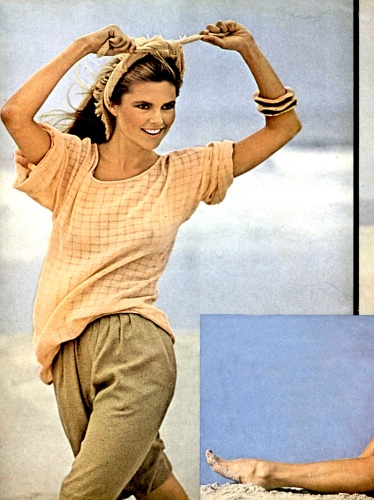

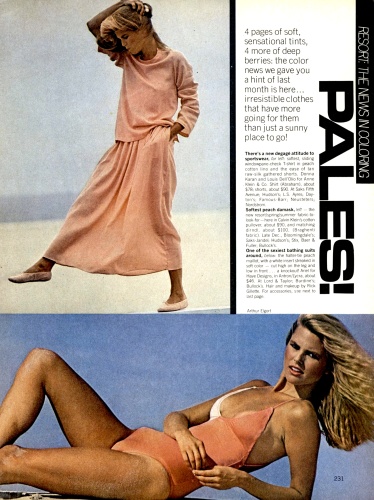

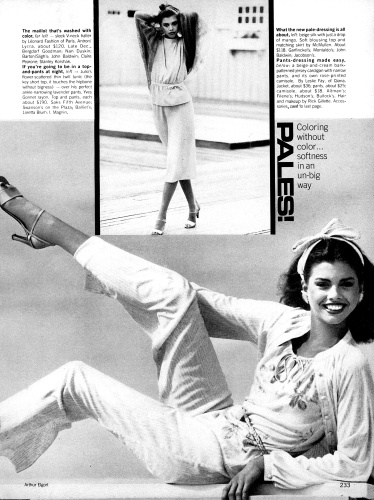

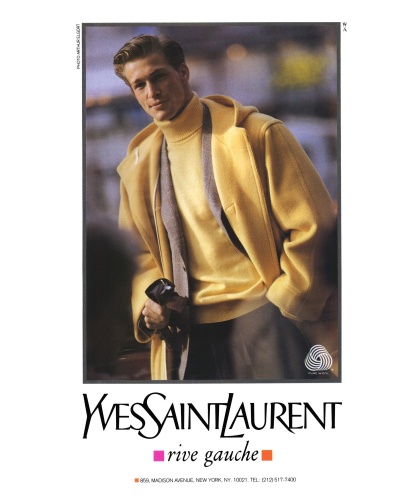

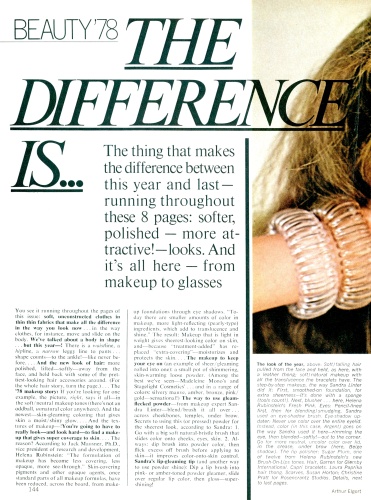

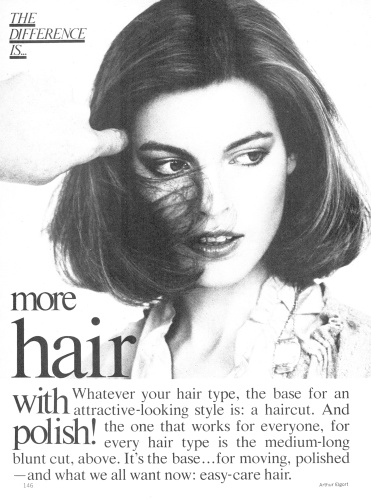

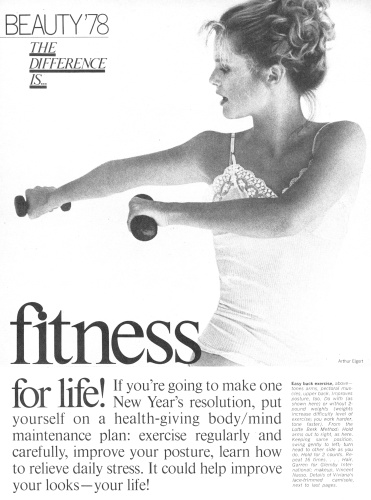

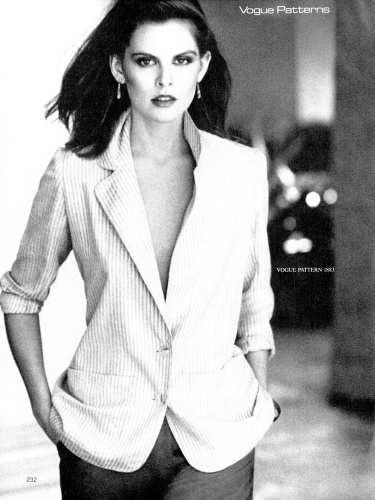

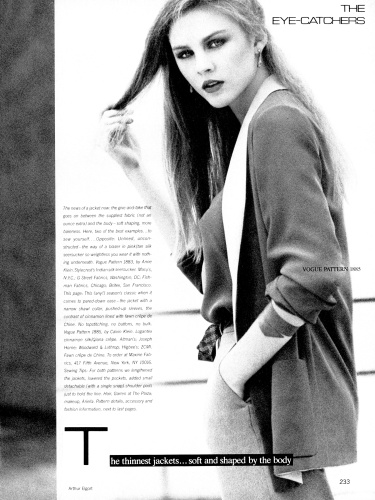

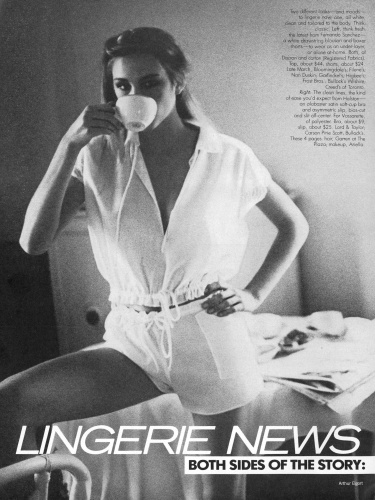

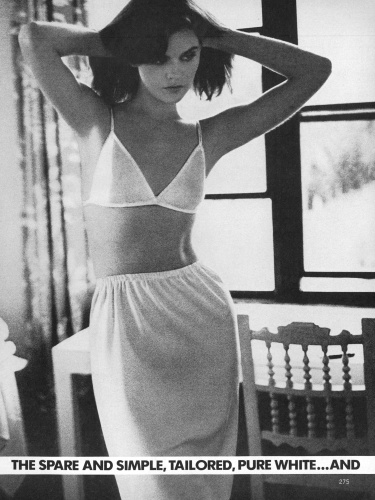

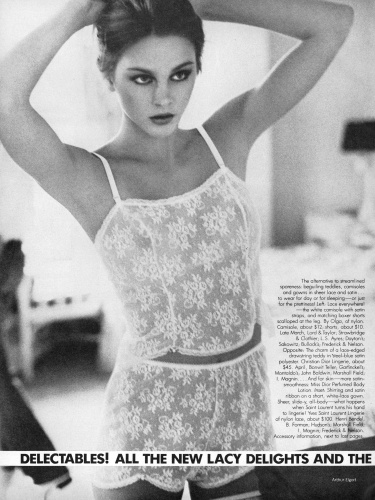

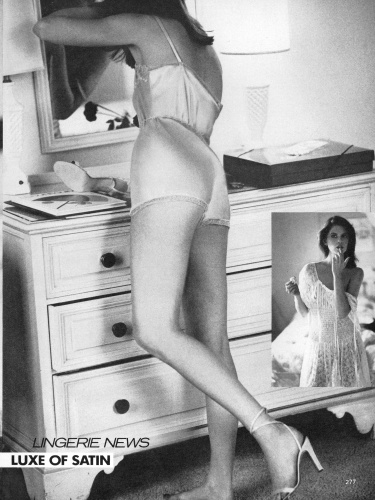

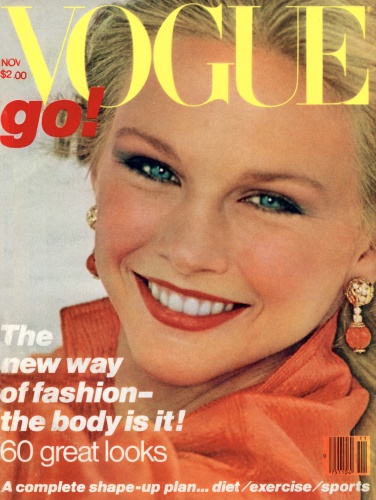

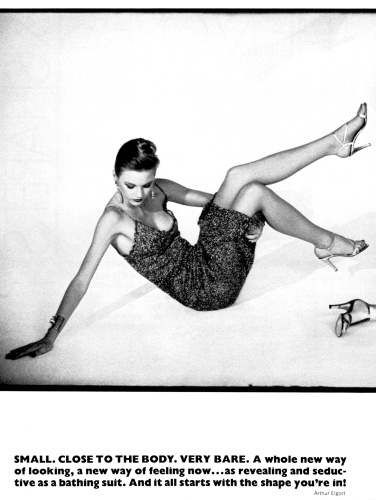

Arthur Elgort - Photographer

- Thread starter Estella*

- Start date

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2010

- Messages

- 102,511

- Reaction score

- 67,212

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2010

- Messages

- 102,511

- Reaction score

- 67,212

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2010

- Messages

- 102,511

- Reaction score

- 67,212

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2010

- Messages

- 102,511

- Reaction score

- 67,212

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 202

- Views

- 93K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)