You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Edward Steichen - Photographer

- Thread starter SomethingElse

- Start date

electricladyland

Active Member

- Joined

- Sep 7, 2005

- Messages

- 8,966

- Reaction score

- 0

Attachments

tigerrouge

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 25, 2005

- Messages

- 19,005

- Reaction score

- 10,077

Thestar.com carried a piece about Steichen:

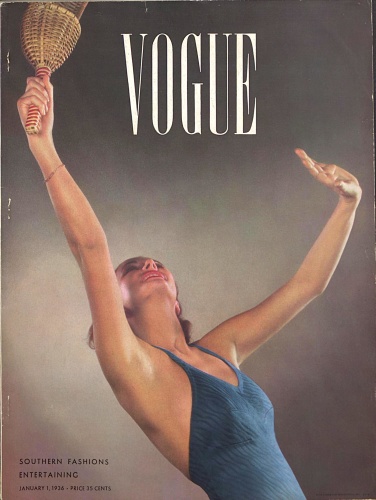

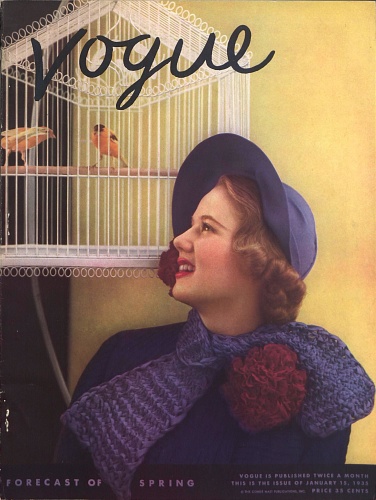

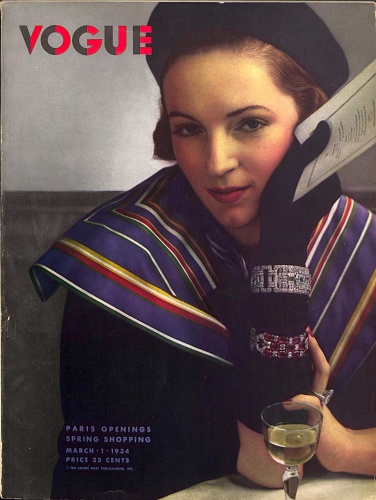

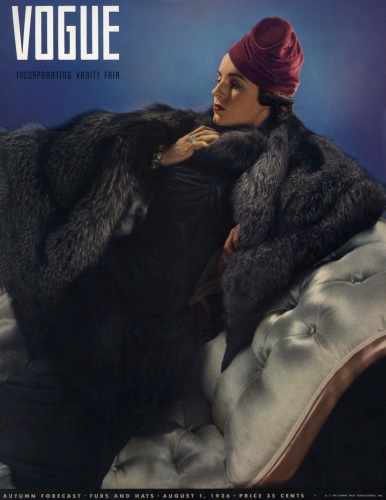

Today's supermodels owe thanks to Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen revolutionized fashion photography and gave it artistic credibility

Sep 24, 2009

News of Annie Leibovitz's financial woes may have come as a surprise, but not so much the sums involved, around $24 million (U.S.), a figure based to a great degree on the worth of her photographs. After all, isn't that the kind of dough we expect star photographers to rake in?

It may seem that wealthy celebrity fashion photographers have been with us forever, from Leibovitz and Oliviero (Benetton ads) Toscani back to Richard Avedon and Cecil Beaton. That's not the case.

Most of their careers – and much of their art – were defined first by Edward Steichen, the American photographer and curator who dominated his profession for some 50 years and who yet died somewhat forgotten in 1973, aged 93.

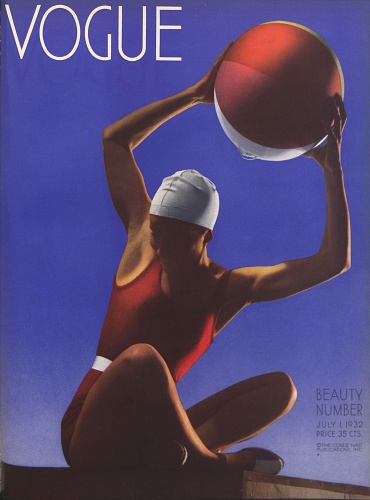

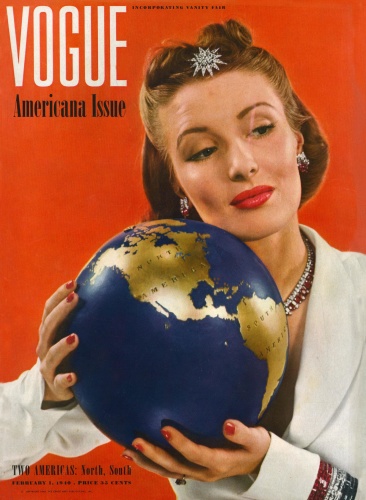

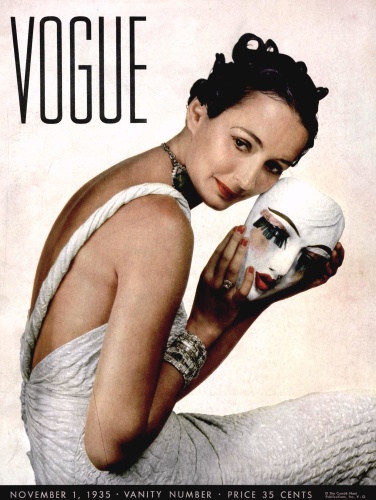

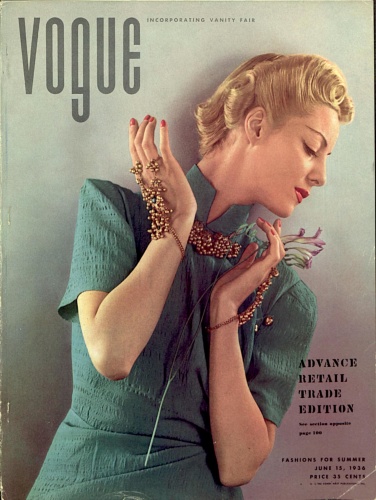

"Edward Steichen: In High Fashion, the Condé Nast Years, 1923-1937," opening at the Art Gallery of Ontario Saturday – paired with "Vanity Fair Portraits: Photographs 1913-2008" at the Royal Ontario Museum, also starting Saturday – zooms in on Steichen's early career as an art student around New York with a huge ambition and in need of money.

"High Fashion" also rolls out the template for what much of fashion photography was to become, when celebrity played as big a role in the fashion shoot as the clothes do.

The arrival of talking pictures in the 1920s created a new class of fame and celebrity and a new public, which demanded to look more closely at them.

"Steichen was one of the first to use actors in a fashion shoot for a melding of art, fashion, film and theatre," Sophie Hackett, the AGO's assistant curator for photography, told me at the gallery as the Steichen exhibition was being put into position earlier this week. "He was prescient in knowing that this was the culture of the day."

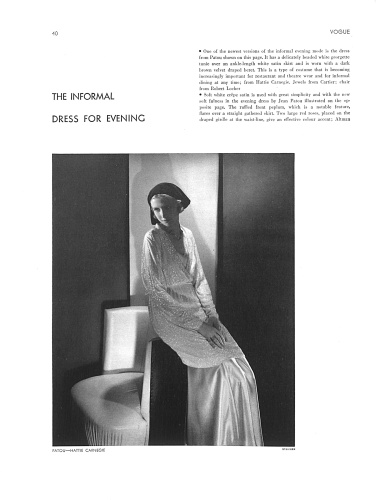

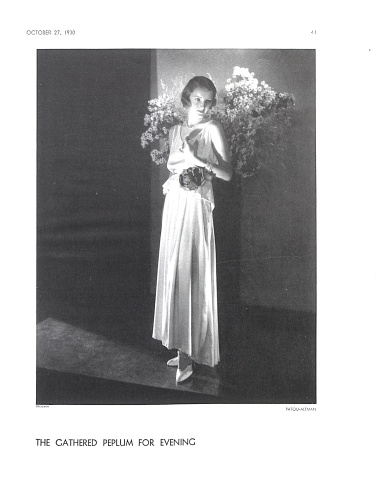

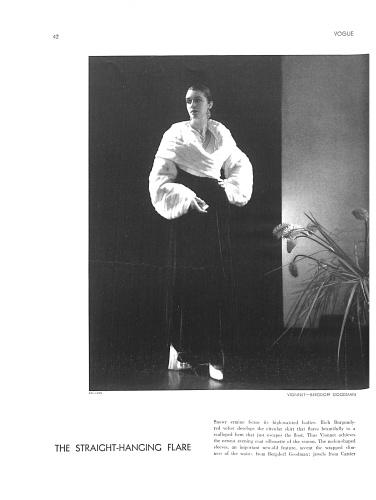

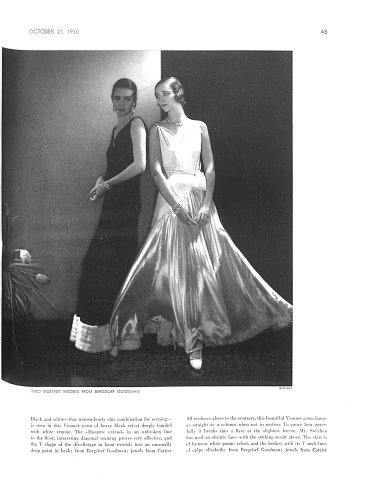

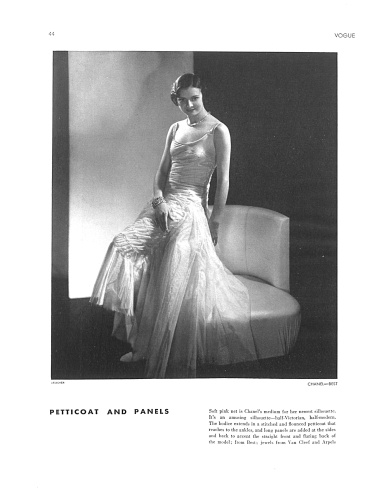

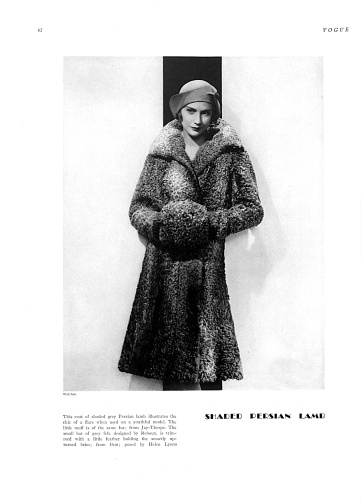

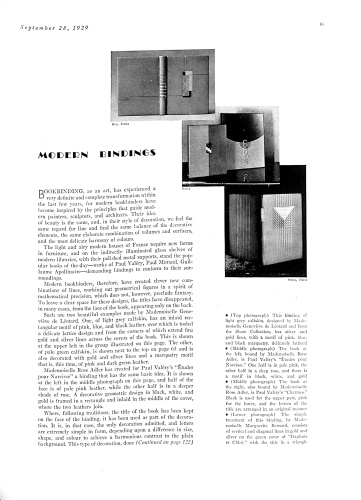

Hackett's layout of the images differs from the chronological format favoured by earlier versions of this well-travelled exhibition. One AGO space is mostly turned over to Steichen's fashion work; the luminous shots of Chanel evening clothes or idealized images of perfect blond children frolicking in high-end clothes on a millionaire's yacht.

The second AGO space is given over to Steichen's celebrities such as crooner Al Jolson looking as devious as a pickpocket who's just purloined the crown jewels. With its sober Charlie Chaplin, or smouldering Pola Negri, the AGO celebrity suite runs parallel to the ROM's show of Steichen's work in the "Vanity Fair Portraits" exhibition and with work from Helmut Newton, Nan Goldin, Liebovitz and Bruce Weber.

Lured away from his career as a painter and art photographer in Paris, Steichen arrived in New York in 1923 with the promise of big bucks from Condé Nast, the fashionable publishing giant, along with access to its two flagship publications, Vogue and Vanity Fair. Nast needed Steichen badly, having had just seen his resident photographer, Baron de Meyer, decamp to Harper's Bazaar, owned by Nast's hated rival, William Randolph Hearst.

Always the careerist, Steichen went along for some years with Vogue's older, luxury-driven, high-society pictorial approach to fashion photography. He knew that before his arrival, society women modelled little frocks from Chanel or Vionnet for Vogue because only they could afford to buy those little frocks from Chanel or Vionnet. And they wanted their photo to have all the classy quality of a Monet.

Eventually, Steichen's well-honed instincts for newness itself took over. Almost overnight, the new Vogue was entirely in synch with the emergence of The Flapper, the jazz-age woman and her newly found sense of liberation.

You can find "the evolution of the idea of femininity," Hackett explained. "It wasn't something Steichen invented. But he was a player in representing this evolution back to the people. You can see why Marion Morehouse was his favourite model. She always looks very confident. She had those long, long greyhound legs. She had poise. Her face was an almost perfect oval. She was created in perfect graphic form. Morehouse can in fact be called one of the first supermodels."

Steichen, who worked with ease in every media he could get his hands on – motion pictures, collage and more – was equally influential in shaping modern magazine design with considerable input coming from the Ukrainian-born Mehemed Fehmy Agha, appointed Condé Nast art director in 1928.

Dramatically lit, Steichen's shots were designed to emphasise which key elements were to emerge from a volume of space. Designers were flattered to see their clothes appear with such drama. Stars were pleased to see their star quality revealed even more clearly to the public. Condé Nast was happy, too. Steichen's clarity of contrasts allowed each picture to hold its own under the demands of the era's new high-speed printing presses.

Hackett iterates a favoured Steichen catchphrase: "Take good photographs and the art will take care of itself."

"Edward Steichen: In High Fashion, the Condé Nast Years, 1923-1937" at the Art Gallery of Ontario and "Vanity Fair Portraits: Photographs 1913-2008" at the Royal Ontario Museum run from Saturday to Jan 3, 2010.

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

New Posts

-

-

Chanel Pre-Collection S/S 2026 : Jacqui Hooper, Betsy Gaghan & Tara Falla (10 Viewers)

- Latest: PDFSD

-

-

-