Squizree

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 18, 2006

- Messages

- 19,515

- Reaction score

- 3,668

I know this is an old thread but I read a VERY interesting article from the Wall Street Journal today.

wsj.com

Survival of the Finest

With Americans and Europeans forgoing couture for ready-to-wear, design houses are looking to the Middle East and Russia to fill the void. Is this couture’s swan song?

They had flown to Paris from St. Petersburg, Jakarta, Abu Dhabi and Monaco for the afternoon customers-only showing of Christian Dior spring/ summer 2010 that took place the second day of couture week in January. Older ladies with sprayed helmets of hair and cascades of diamonds nestled on white wooden folding chairs next to girls in their 20s in five-inch stilettos with sable trench coats or ostrich jackets trimmed in chinchilla. “We are here not just to look, but to buy,” said Svetlana Metkina, 36, a Russian actress who is married to a producer and keeps an apartment in Paris as well as homes in Moscow and Los Angeles. She dropped her BlackBerry into the $23,000 purple snakeskin Birkin bag that lay at her feet as the models began their procession in John Galliano’s floor-sweeping dresses inspired by 19th-century riding costumes. “We are the only ones crazy enough to take them seriously,” she whispered. “They appreciate that, especially now.”

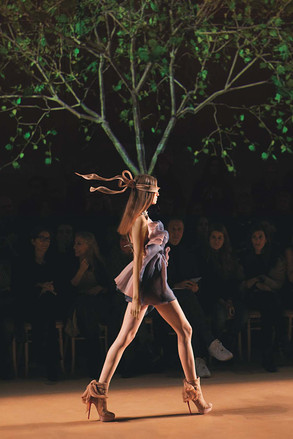

A model walks the runway at Valentino’s Garden of Eden–inspired spring/summer 2010 couture show.

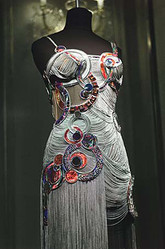

It’s no wonder Metkina senses the couture houses are humbled. These are unsettled times for everyone in the business of luxury, but the challenges facing this rarefied world are as unique as a $350,000 hand-beaded pistachio silk ball gown with an embroidered peplum. With buyers in retreat, its traditional customers aging or dying, and critics increasingly carping about its irrelevance, the couture economy, always delicate, now is more precarious than ever, leaving many to wonder whether there is a customer base left for couture.

Green sequin heels by Givenchy (with a nod to Dorothy) await a model’s feet.

Gone are the high-class tastes of old-world American society, the blue-blooded ladies who lunched and hosted benefits and social events in couture daywear having been replaced by new-world billionaires—from the Middle East and Russia. For this very moneyed class, it’s less about the luxuriousness of wearing exquisite handmade to-order creations and more about conspicuous consumption and making museums out of their closets. But couture is much more than a product. It’s a creative engine for an entire brand, a marketing tool, the foundation of an image on a profound, long-term level. Middle Easterners and Russians don’t bring couture the publicity and recognition it needs to maintain its allure.

Furthermore, couture designers are faced with two other problems: the overall shift of young people everywhere to a more casual style and the fact that many of the ready-to-wear companies are raising quality and prices and keeping volume low (and exclusivity high), precisely to lure a new generation of wealthy buyers, exactly those who years ago would have probably bought couture.

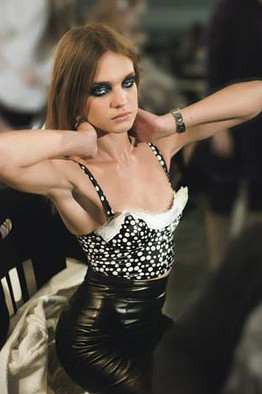

A Givenchy model gets deep red lipstick before the show.

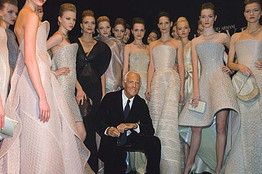

All of this has forced designers to rethink couture. Some, like Valentino and Givenchy, are taking radical steps to modernize and appeal to younger women. Others are seeking to bridge the gap through a new movement: made-for-occasion couture, which mostly caters to the celebrities in need of gowns each Hollywood awards season. They may not pay for the couture gowns they wear, but they walk red carpets and provide fashion houses with a global platform to keep couture on everyone’s radar. Elie Saab, though much of the industry turns its nose up at his intricately detailed beaded creations, figured this out years ago. Armani, Gucci and Versace are playing catch-up.

To call couture a business has long seemed generous. The age-old art of handmaking and custom-fitting intricate one-of-a-kind garments surely would have died out by the late 1980s had corporations such as Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy not scooped up some of the few remaining brands. The multinationals placed the ateliers—workrooms with dozens of European-trained craftspeople—at the top of a newly created fashion food chain, recasting them as artistic laboratories and image drivers for the real potential profit centers: ready-to-wear, accessories and perfumes. Still officially sanctioned by the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture (there are 11 French houses left, half of them niche players with tiny followings, and several foreign “correspondent” members), the ateliers continue to churn out confections that defy gravity and the imagination, but contributing to the bottom line has long been secondary. Numbers are as hard to come by as the dresses themselves, but experts say that selling several dozen a season—that’s all even the biggest houses claim—does little more than take the edge off the staggering costs of staging massive multimillion-dollar fashion shows and maintaining the staff of trained embroiderers, pattern-cutters and tailors. “Admittedly, couture is not something that is easy to look at as a mere balance-sheet calculation,” says Stefano Sassi, CEO of Valentino, an associate correspondent Syndicale member.

wsj.com

dont worry about it.

dont worry about it.