“He’s like a school, not a designer,” Glenn Martens said, referring to

Martin Margiela, whose work for both his own label and Hermès has influenced a great many designers. Margiela long ago retired and sold his brand to Renzo Rosso of the OTB Group, which also owns Marni, Jil Sander, and Diesel. John Galliano designed the Artisanal collection for Margiela for a decade

until last year. His January 2024 collection, held under a bridge in Paris at night, was one of the

most talked-about shows in recent history.

Maison Margiela is now in Martens’s hands. A few days before his debut, on Wednesday, Martens, best known for his work with Diesel and the former Y/Project label, said he had to consider the fact that Margiela had already been interpreted by many designers. He was in his native Bruges last Christmas thinking about a difference he could make, at least as a start. He told me, “Martin always had a gloominess. I wanted that austerity. Everything’s kind of in a rainy fog.”

In Bruges, Martens visited museums and historical places, looking at art and architecture, mostly from the 16th and 17th centuries. The gloom of European long winters was easy to find, as were the texture and hues of Renaissance wallpapering techniques in embossed leather. That idea, its peeling layers and faded colors, led Martens and his team to create a similar effect with paper, making photocopies of images, collaging them, ripping them, and sometimes putting candle wax on them. Or perhaps a coat of varnish. The base layer of those garments was usually leather.

Even at close range, with touch, it was hard to make out the origin of the materials. For the show, in an underground series of rooms, Martens had the walls papered in the same crumbling tones; had the audience not been between the models and the walls, you’d swear some of the models — their heads covered with helmetlike masks made of metal and reclaimed beads and crystals — were specters suddenly emerging from the walls, Flemish history animated.

Martens attempted to retain some of Margiela’s conceptual purity (you could say) by keeping his shapes relatively simple and somewhat in line with early Margiela — his long wrap skirts with basic cloth ties and his plain, almost drab knits. He often used everyday things, like clear plastic garment bags (the kind used in factories), recycled fabrics and fur coats, synthetic wig hair, and the elements of a Stockman dress form, to mention just a few objects that helped Margiela transform people’s perceptions about dress. He was also history-minded, alive to the sartorial connections to different periods.

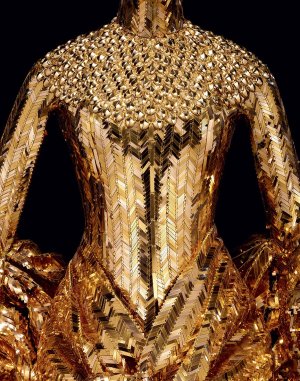

Martens’s first collection certainly had some of that spirit and a great deal of his own maximalist passion for material techniques. These included a golden wad of a dress made from computer wires, a fabric produced by a Swiss textile-maker, and a number of plastic styles, some draped or wadded and then contained in a dome of plastic. These seemed more of an academic exercise than a resolved proposition. They didn’t push anything forward, in my view, and I can imagine they must be bloody hot, a heat dome.

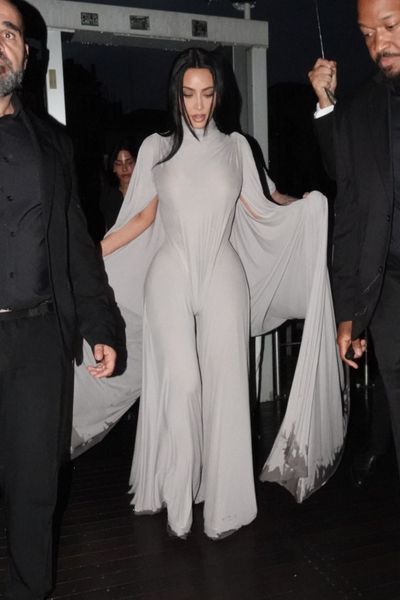

The garments made of collaged paper on leather were more convincing, as were a kind of Grim Reaper cloak in hand-painted canvas and a superb gown, super plain and fitted through the bodice, in black polyester. I generally liked most of his lighter-weight dresses, in both murky and pale colors, with 3-D embellishment in the same hues.

But the rigidity and weight of many of the clothes were counter to Margiela’s principle of things being worn in the streets, however new and strange they looked. That would be an interesting challenge to Martens, to make these Artisanal pieces also real.

The company now plans to take customer orders for its Artisanal line, its equivalent of couture. That wasn’t possible during the Galliano years, unfortunately, because the company didn’t have the structure. About 30 people have booked appointments.