the boston globe today had a story this week about perfumer.

he wants us to change the way we appreciate fragrances.

he is responsible for these top sellers.

Ralph Lauren "Polo Blue for Men"

Clinique "Happy Heart"

Abercrombie & Fitch "Fierce"

"Island" Michael Kors

Tom Ford Estée Lauder Collection "Youth Dew Amber Nude"

Tommy Hilfiger "Beyoncé True Star"

Elton John's "Black Candle"

Making perfect scents

A chemistry champ who went from MIT to Procter & Gamble to the perfume industry wants to educate your nose

"I have colleagues and clients who tell me I shouldn't be doing this," says Christophe Laudamiel to the standing-room -only audience at Harvard. "People are scared. The whole industry is scared."

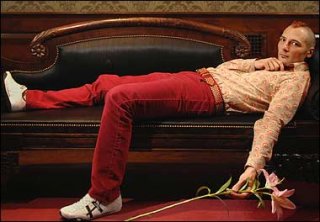

Laudamiel, a renowned perfumer who has created scents for Tom Ford, Ralph Lauren, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Estée Lauder, is clearly enjoying this bit of rabble-rousing. Last week at Harvard, the university where he worked as a teaching assistant in the early 1990s, he lectured to architecture students about scent. But he was also here as part of his own mission, which is to break down what he sees as the perfume industry's perpetuation of "secrecy and mysticism." Throughout the lecture, the 37-year-old native of France with a blazing streak of crimson hair and a propensity to dot his sentences with the word "bon," did his best to shed light on what happens in the labs where fragrance is born.

He showed slides of how scents are distilled from natural ingredients, he passed around scented strips to help train curious noses, and, in perhaps his most brazen move, his PowerPoint presentation included a partial formula for one of his scents.

But Laudamiel, widely regarded as one of the rising stars of the fragrance world, says this radical approach is necessary for the perfume industry to come out of its malaise. He wants to educate your nose and he wants you to finally understand the components of the Escada bottle sitting on your vanity. In the same way that wine snobs can cite the ingredients of the liquid that they swish between their cheeks, Laudamiel thinks it's time that fragrance followers understand that a perfume can contain up to 100 individual elements.

"There's too much confusion, too much secrecy," he says. "I think perfumery should be raised to the same level as music, and painting, and architecture. With a symphony orchestra, you can see all the music, you can see all the instruments, and in the end it's still magical. When you're educated, you can determine the true value of things, and you can make better choices. It's time for that same level of education to occur with scent."

Laudamiel, who now lives in New York, is in some ways an unlikely figure to become the new voice of nasal education. A national chemistry champ in France, he studied at MIT for a year before studying and working at Procter & Gamble Co . He started creating flavors for cough syrup and toothpaste at P & G, before graduating with his Perfume-Creator degree. He now works as a fine-fragrance perfumer at International Flavors & Fragrances.

There are about 2,000 scents (Laudamiel refers to them as molecules) that perfumers can use to create new fragrances; he estimates that he has trained his nose to identify about 1,500 of them. He is incredibly passionate about the topic of scent. His business cards are even scratch and sniff. But he admits that when it comes to small talk and more personal exchanges, he is quite demure, despite his brightly hued wardrobe.

"He is a new breed of perfumer," says Rochelle Bloom, president of the nonprofit Fragrance Foundation. "He's not the kind of perfumer who stays in the lab. He's someone who I can see developing fragrances under his own name someday."

Laudamiel has started working with the Fragrance Foundation on a program that he hopes will bring olfactory training to all public schools. "We are now going into phase two of the program to find out what would be appropriate for the curriculum of schools," he says over poached eggs the morning after his Harvard lecture. "This is a time when kids are learning a new language or starting music or drawing. Scent is just another sense that they have to awaken."

He explains that there are 350 scent receptors in a human nose (about 60 percent fewer than a rat or a dog, but enough to do the job properly); however, most people use only a fraction of that. His hope is that trained noses will develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for the fine notes in a perfume. You may never reach the level of determining if that hint of orange you smell is extracted from a Brazilian orange rather than a California orange (yes, there is a difference in their fragrance), but perhaps you can start to appreciate some of the 300 molecules that make up the scent of a rose.

In addition to preaching the gospel of scent, Laudamiel spends his free time creating scents. In 1994, when still studying perfumery at Procter & Gamble, he read Patrick Süskind's "Das Perfum," a book about a murderous perfume maker in 1700s Paris with an extraordinary gift for scent. In 2000, he began working on replicating scents from key scenes of the book on nights and weekends. Some of these scents were pleasant, such as jasmine, or the leathery Salon Rouge. Others, however, such as Orgie, Paris 1738 and Virgin No. 1, are not the usual pretty scents. They are atmospheric fragrances intended to turn Süskind's evocative words into reality.

When he heard that the book was being made into the film "Perfume: The Story of a Murderer," he and partner Christoph Hornetz, who'd helped him develop these fragrances, contacted Thierry Mugler perfumes, one of France's more innovative perfume houses, about the project.

Last year, to coincide with the film's release, Thierry Mugler released a limited-edition coffret, or collection, of 15 film-inspired scents. The $700 collection sold out in Europe; it is still available in the United States. Like most things Laudamiel does, the "Perfume" coffret was more about sharing the love of fragrance than simply making money.

"I think people want to be challenged, they want to go deeper into perfumery; they just haven't had the opportunity," he says. "As soon as I stepped into perfumery, I could see all the fluff, and sometimes the bluff. I hate to lie to people and to take them for less intelligent than they are. But when you educate people about scent, you make it more interesting for the public, and that's how you make things more interesting for your own discipline. You get better challenges, more interesting questions, and much better projects."

he wants us to change the way we appreciate fragrances.

he is responsible for these top sellers.

Ralph Lauren "Polo Blue for Men"

Clinique "Happy Heart"

Abercrombie & Fitch "Fierce"

"Island" Michael Kors

Tom Ford Estée Lauder Collection "Youth Dew Amber Nude"

Tommy Hilfiger "Beyoncé True Star"

Elton John's "Black Candle"

Making perfect scents

A chemistry champ who went from MIT to Procter & Gamble to the perfume industry wants to educate your nose

"I have colleagues and clients who tell me I shouldn't be doing this," says Christophe Laudamiel to the standing-room -only audience at Harvard. "People are scared. The whole industry is scared."

Laudamiel, a renowned perfumer who has created scents for Tom Ford, Ralph Lauren, Abercrombie & Fitch, and Estée Lauder, is clearly enjoying this bit of rabble-rousing. Last week at Harvard, the university where he worked as a teaching assistant in the early 1990s, he lectured to architecture students about scent. But he was also here as part of his own mission, which is to break down what he sees as the perfume industry's perpetuation of "secrecy and mysticism." Throughout the lecture, the 37-year-old native of France with a blazing streak of crimson hair and a propensity to dot his sentences with the word "bon," did his best to shed light on what happens in the labs where fragrance is born.

He showed slides of how scents are distilled from natural ingredients, he passed around scented strips to help train curious noses, and, in perhaps his most brazen move, his PowerPoint presentation included a partial formula for one of his scents.

But Laudamiel, widely regarded as one of the rising stars of the fragrance world, says this radical approach is necessary for the perfume industry to come out of its malaise. He wants to educate your nose and he wants you to finally understand the components of the Escada bottle sitting on your vanity. In the same way that wine snobs can cite the ingredients of the liquid that they swish between their cheeks, Laudamiel thinks it's time that fragrance followers understand that a perfume can contain up to 100 individual elements.

"There's too much confusion, too much secrecy," he says. "I think perfumery should be raised to the same level as music, and painting, and architecture. With a symphony orchestra, you can see all the music, you can see all the instruments, and in the end it's still magical. When you're educated, you can determine the true value of things, and you can make better choices. It's time for that same level of education to occur with scent."

Laudamiel, who now lives in New York, is in some ways an unlikely figure to become the new voice of nasal education. A national chemistry champ in France, he studied at MIT for a year before studying and working at Procter & Gamble Co . He started creating flavors for cough syrup and toothpaste at P & G, before graduating with his Perfume-Creator degree. He now works as a fine-fragrance perfumer at International Flavors & Fragrances.

There are about 2,000 scents (Laudamiel refers to them as molecules) that perfumers can use to create new fragrances; he estimates that he has trained his nose to identify about 1,500 of them. He is incredibly passionate about the topic of scent. His business cards are even scratch and sniff. But he admits that when it comes to small talk and more personal exchanges, he is quite demure, despite his brightly hued wardrobe.

"He is a new breed of perfumer," says Rochelle Bloom, president of the nonprofit Fragrance Foundation. "He's not the kind of perfumer who stays in the lab. He's someone who I can see developing fragrances under his own name someday."

Laudamiel has started working with the Fragrance Foundation on a program that he hopes will bring olfactory training to all public schools. "We are now going into phase two of the program to find out what would be appropriate for the curriculum of schools," he says over poached eggs the morning after his Harvard lecture. "This is a time when kids are learning a new language or starting music or drawing. Scent is just another sense that they have to awaken."

He explains that there are 350 scent receptors in a human nose (about 60 percent fewer than a rat or a dog, but enough to do the job properly); however, most people use only a fraction of that. His hope is that trained noses will develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for the fine notes in a perfume. You may never reach the level of determining if that hint of orange you smell is extracted from a Brazilian orange rather than a California orange (yes, there is a difference in their fragrance), but perhaps you can start to appreciate some of the 300 molecules that make up the scent of a rose.

In addition to preaching the gospel of scent, Laudamiel spends his free time creating scents. In 1994, when still studying perfumery at Procter & Gamble, he read Patrick Süskind's "Das Perfum," a book about a murderous perfume maker in 1700s Paris with an extraordinary gift for scent. In 2000, he began working on replicating scents from key scenes of the book on nights and weekends. Some of these scents were pleasant, such as jasmine, or the leathery Salon Rouge. Others, however, such as Orgie, Paris 1738 and Virgin No. 1, are not the usual pretty scents. They are atmospheric fragrances intended to turn Süskind's evocative words into reality.

When he heard that the book was being made into the film "Perfume: The Story of a Murderer," he and partner Christoph Hornetz, who'd helped him develop these fragrances, contacted Thierry Mugler perfumes, one of France's more innovative perfume houses, about the project.

Last year, to coincide with the film's release, Thierry Mugler released a limited-edition coffret, or collection, of 15 film-inspired scents. The $700 collection sold out in Europe; it is still available in the United States. Like most things Laudamiel does, the "Perfume" coffret was more about sharing the love of fragrance than simply making money.

"I think people want to be challenged, they want to go deeper into perfumery; they just haven't had the opportunity," he says. "As soon as I stepped into perfumery, I could see all the fluff, and sometimes the bluff. I hate to lie to people and to take them for less intelligent than they are. But when you educate people about scent, you make it more interesting for the public, and that's how you make things more interesting for your own discipline. You get better challenges, more interesting questions, and much better projects."