-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

RIP Helmut Newton - 1920-2004

- Thread starter ChillChaser

- Start date

I am saddened to report that the fashion photographer , HELMUT NEWTON has been killed in a car crash , in his Cadillac , in LA.

He was 83 and will be greatly missed , I feel sure .

His photograph of the model in the YVES SAINT LAURENT ' Le Smoking suit ' will live for all time as one of the greartest fashion shots EVER .

Yours , in despondency , KIT

He was 83 and will be greatly missed , I feel sure .

His photograph of the model in the YVES SAINT LAURENT ' Le Smoking suit ' will live for all time as one of the greartest fashion shots EVER .

Yours , in despondency , KIT

Something relevant and interesting , here :-

http://observer.guardian.co.uk/internation...1130576,00.html

Regards KIT B)

http://observer.guardian.co.uk/internation...1130576,00.html

Regards KIT B)

this morning we went to the site were the accident was. i just couldn't believe it. where he exited and where the wall that he crashed into couldn't have been more than forty feet apart. or less. it was a very narrow two lane road.

i felt numb. all i could think was, he barely drove at all. this just can't be happening.

there was a man standing in front of a limo in front on the curb. there were two bouquets of flowers lying there.

the weird thing was when we got out of our car (we parked down the street) another car drove up and parked in front of us. donaven leitch and his wife kristy hume (former model) (who is pregent by the way) got out of the car and walked into the hotel.

i have a feeling helmut's wife was there ( i have read on report that said she was in the car with him). and that dono and kristy were going there to visit her. because if people were gathering just to be with eachother i doubt they would go directly to where it happend because that would be to morbid. but unless someone was already there for an important reason, like his wife.

i think he had a heart attack while driving.

he did lead an amazing life, and i feel fortunate that i get to experience his brillance, yet this just all feels so devistating.

i felt numb. all i could think was, he barely drove at all. this just can't be happening.

there was a man standing in front of a limo in front on the curb. there were two bouquets of flowers lying there.

the weird thing was when we got out of our car (we parked down the street) another car drove up and parked in front of us. donaven leitch and his wife kristy hume (former model) (who is pregent by the way) got out of the car and walked into the hotel.

i have a feeling helmut's wife was there ( i have read on report that said she was in the car with him). and that dono and kristy were going there to visit her. because if people were gathering just to be with eachother i doubt they would go directly to where it happend because that would be to morbid. but unless someone was already there for an important reason, like his wife.

i think he had a heart attack while driving.

he did lead an amazing life, and i feel fortunate that i get to experience his brillance, yet this just all feels so devistating.

keepsmiling

Member

- Joined

- Oct 26, 2002

- Messages

- 377

- Reaction score

- 4

I would have felt sick looking at where he died.

I would have felt sick looking at where he died.mikeijames

no tom ford, no thanks.

- Joined

- Nov 27, 2003

- Messages

- 5,879

- Reaction score

- 8

helmut newton, dear.

marc jacobs addict

Active Member

- Joined

- Dec 1, 2003

- Messages

- 1,064

- Reaction score

- 9

Helmut Newton: Lensman Provocateur

By Jacob Bernstein

NEW YORK — Helmut Newton, the legendary photographer whose sexually provocative images captured everything from Yves Saint Laurent in the era of Le Smoking to Amazonian women in corsets and Wolford tights, died on Friday in a car accident in Los Angeles. He was 83.

According to witnesses, Newton had gotten in his car outside the Chateau Marmont, where he resided with his wife June during the winter months each year. He began to drive slowly out of the driveway, then lost control and collided with the wall on the opposite side of the road. He was rushed to Cedars Sinai Hospital, where he was pronounced dead around noon local time.

For more than 40 years, Newton was one of the most prolific photographers in fashion. His controversial photographs appeared everywhere from Vogue to The New Yorker and he became associated with many designers whom he worked with, none more so than Saint Laurent.

“We have lost a superstar of photography,” said the designer. “He started the S&M trend and he was one of the stars of the Pop period. Technically, he was irreproachable.”

He was however, wildly influential. One can see his techniques in the shoots of Ellen Von Unwerth, Deborah Turbeville and Steven Klein. In fashion, his sensibility has colored the sexually charged work of younger designers like Helmut Lang and Tom Ford.

“I think that Tom’s idea of the strong woman with the makeup and the heels and the groomed hair and the strong mouth was influenced as much by Helmut’s photography as the clothes of Saint Laurent,” said Anna Wintour, editor in chief of Vogue.

Indeed, Ford himself said, “His photographs are burned into my subconscious.”

“We always looked to Helmut for something provocative and surprising and wicked,” continued Wintour. “When we did our Shape issue he immediately called with the idea of pairing a plus-size model with a little diminutive man. He could always put a twist on things. When we asked him to do high heels, he put Nadja Auermann on crutches. He always wanted to know how much hate mail we were getting on his pictures.”

Newton was born Helmut Neustadter in Berlin in 1920 on Halloween, the son of a widow and a bourgeois button manufacturer, who was also a secular Jew. His mother had a child from a previous marriage and although her second marriage was a terrific one, it was not entirely conventional. His parents had been married the previous March. His mother told her son that he was born two months premature, but family friends later told Newton this was simply to cover up that that she was two months pregnant when she married his father.

Newton grew up in the Weimer Republic in the decadent era of post-World War I Germany. Although many artists obsessed with sex are the ones repressed by it, Newton’s childhood points to the opposite.

“Berlin was always a city of music,” he wrote in his memoir, “Helmut Newton: Autobiography,” published last fall. “Throughout the Twenties and Thirties, American jazz bands performed regularly in the clubs and cabarets and were immensely popular. We were mad for jazz. I especially loved Cab Calloway, Jack Hylton, Duke Ellington, and all the Big Bands.”

As a child, Newton and his friends would skip school to go to the bars along the Tauentzienstrasse, where they would smoke cigarettes and dance with housemaids. “We only did it to get a hard-on and try to rub ourselves off against them,” he wrote.

When he lost his virginity at the age of 14, his mother gave him condoms, and told him only to have sex once a week, saying that sex would distract him from his schoolwork.

She was right. He was a terrible student.

By this point, he was already taking pictures, having gotten his first camera at the age of 12. His parents asked him what he wanted to do. He told them he wanted to be a movie cameraman or a photographer.

“All you think of is girls and photos,” complained his father.

Gravitas arrived shortly thereafter.

At the age of 18, the Nazis rounded up his father. Young Helmut spent two weeks in hiding, before his mother learned of a postbox at the Gestapo headquarters where one could post a letter to, and get a release, as well as passports to leave the country.

Thanks to a kindly Gestapo officer, Newton’s father was released and the family was able to get passports to leave the country. Weeks later, Helmut boarded a train to Singapore.

All of this infused his later work. Straddling the line between fashion and p*rn*gr*phy, Newton would photograph Amazonian women in erotically charged situations that expressed an adolescent wonder at the female body as well as a sense of something darker lurking underneath. The woman in high heels would be enticing, but the mix of stark lighting and her shadow looming prominently behind her suggested something kinkier, dangerous even. It is, of course, the product of a young man whose sexual awakening was interrupted by the Holocaust. His photographs captured the opposing forces of desire and guilt.

“He would look at violence, it could be a war picture, something he saw in the paper, things stuck with him,” said the stylist Polly Mellen, with whom he worked for Vogue in the Seventies. “He would transfer a thought that was part of seeing something morbid, something that would trigger him.…It was a whole different thing from beauty. He awoke in me salacious thoughts. p*rn*gr*phy is something that always interested him. There was this ‘yes, OK Helmut, but that’s p*rn*gr*ph*c’ and so then we would bring it back to something that’s more mysterious. That’s what interested him. He took it further than any photographer I ever worked with aside from Terry Richardson, but it was always classy, always glamorous. The word was suggestive.”

His work went beyond fashion photography. In the Eighties, Tina Brown called on him to work for her at Vanity Fair and then at The New Yorker.

“His first great coup was to do a photo of Claus Von Bulow in head-to-toe black leather on the eve of his trial to go with Nick Dunne’s coverage,” Brown remembered. “It made a news sensation and of course was reproduced everywhere.…He did my very first cover of Vanity Fair of Daryl Hannah blindfolded with the cover line ‘Blonde Ambition,’ very S&M for the Eighties. He would often call and say, ‘Give me a hot assignment. I feel like ambulance chasing.’ He loved working for the New Yorker for the same reason. He got to do powerful portraiture, like one he did of a death-penalty judge with his coat flying like a cape of evil.”

“His life and his closeness with June was very important to his work,” explained Wintour. He met June Browne in 1946 when she came to see him about modeling work. They married two years later, and she was a frequent subject for him until the end of his life. Newton even photographed her as Adolf Hitler.

Recently, when his health was not as robust as it had been, he became interested in doing shoots in hospitals with doctors.

His friend Karl Lagerfeld pointed to the way in which Newton’s own experiences infused his imagery. “If he would have seen his accident, he would have taken a picture of it,” the designer said

todays WWD.com

such a brilliant man.

such a brilliant man.MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,613

- Reaction score

- 1,357

June Newton aka Alice Springs [1923 - 2021]

June Newton

Helmut Newton was “the King of Kink,” but his wife, who died at 97 in Monte Carlo, was the mastermind behind the camera

Joan Juliet Buck

In Paris, the past is present and the legends are sociable. The night in 1981 that I first met June and Helmut Newton, at their place on the Rue de l’Abbé de l’Epée, he and I immediately started arguing. I’d come to discuss a text I was supposed to write for one of his photo books, but the expat-in-Paris atmosphere of culture as pleasure was so familiar that I forgot he was a legend and 30 years my senior. I contested what he’d just said. He shouted. I shouted.

June watched with the unfazed appreciation of an actress at a noisy rehearsal, then booked a table and swept us out to a restaurant, because, as we all knew, dinner is the cornerstone of expat survival. And then we were friends for decades of dinners, collaborations, and fun shouting matches. He was Berlin-blunt, she was Melbourne-blunt, and both were like family to their friends, but ever suspicious of the gatekeepers—the editors, the clients. Our friendship collapsed when I became the gatekeeper of French Vogue, and it sprang back to life after I left.

Helmut Newton’s photos conveyed such complex sexual tension that the British press dubbed him “the King of Kink.” People speculated about his relationship with models, what his actual wife looked like, what she knew, what she didn’t know, and what there was to know. One of the sexiest photographs he ever took was of June lighting a cigarette at a dinner table, her dress pulled open to expose her breasts. Married for 56 years, citizens of the world, childless, they loved each other.

June was not an amazon like his models, but a mastermind. Small, energetic, curious, always alert to nuance and depth, primed for approaching bullsh*t, June could see below the surface; her perspicacity could run acid, with a short list of short words to use on a long list of people. Always that tension between enjoying the company of fools and hating them for being fools.

Her face was square, her mouth small, her straight brown hair in a bob. I only saw her wear clothes that were black or white, with some kind of chunky Art Deco bracelet. I didn’t know until very recently that she’d won an award for excellence in theater and played Hedda Gabler on television. “I was an actress” was as much as she said. The photos of her when she was an actress in Melbourne, stage name “June Brunelle,” show a severe expression, a tidy mouth, and the same bangs.

He called her Junie; she called him Helmie.

Their legend was set. They’d met in Melbourne, where she was an actress of 23 and he was a beginning photographer of 27, a German-Jewish refugee released from an internment camp and then from the Australian Army. They married in 1948, and she carried on acting until, and a little after, they moved to Paris in 1957; he worked for French Vogue, was discovered and then rejected by Diana Vreeland, and later re-discovered by Alex Liberman.

While shooting 45 pages for American Vogue in New York in 1971, he had a major heart attack. As he underwent one of many procedures, he photographed himself on his bed, full of tubes. “There is something about a camera,” he wrote in his 2003 autobiography. “It can act as a barrier between me and reality.”

He was too sick to work; June flew to New York, picked up his camera, and completed the assignment. She needed a pseudonym and, in the spirit of irony, chose the name of a small Australian town, Alice Springs.

By 1981, June took only portraits, and not often enough. They were extraordinary, frequently of women, and ran in Vanity Fairand Egoïste, Nicole Wisniak’s large-format black-and-white magazine. That was when a black-and-white photo shot on Tri-X film could be as potent as a thriller. The contrast between her impenetrable black and luminous whites, brought out through the silver-gelatin process by the same, often French, master printers that Helmut used, gave a unique depth and power to the faces she caught on a Pentax camera with a 50-mm. lens.

Helmut’s photos expressed a fantasy of his, a construct or a memory, and were directed, lit, and staged; posed by fashion editors, hair and makeup artists, and assistants; and commissioned by brands or magazines, principally Vogue. June’s portraits were taken in ambient light, with neither editor, nor hair, nor makeup, often for no reason other than her desire to take a picture. She proceeded from a combination of sympathy, curiosity, and respect for the imagined self-image of the subject. I asked June to take portraits of certain people I interviewed. One of the remarkable ones was Marie-Louise von Franz. June went to Küsnacht to shoot the revered 70-year-old Jungian—a small, severe, slight woman—with her bulldog drooling just behind her in the frame, more shadow side than pet.

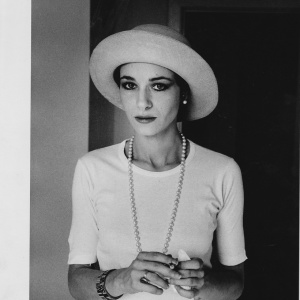

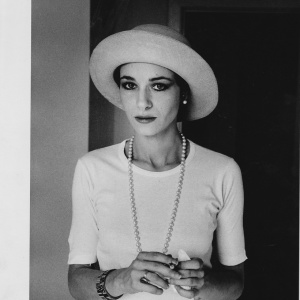

In the 80s, anyone who posed for a magazine feature—politician, actor, artist—was dressed up in sample clothing and amended by a makeup artist to promote a fashion advertiser. June went for the person, and always caught what lay beneath the surface. I’d posed for her as a friend in 1983, in full joy on their terrace at the Chateau Marmont, wearing a T-shirt and my grandmother’s pearls, on a day when I had a secret that made me happy, and it showed. The photo wasn’t published for 34 years.

It was different when she took my portrait in 1987, to go with a magazine story for the launch of my second novel; I was so unsure whom I was trying to be that she had to do three sittings before we had the one usable picture, in which I am pretending to be Romaine Brooks. Or maybe George Sand, or maybe Ronald Firbank.

The socialist victory of François Mitterrand in 1981 scattered those expatriates who actually paid French taxes to easier systems, and that was the end of the glamorous, tasteful life on the Rue de l’Abbé de l’Epée. The Newtons went into tax exile and ended up in the bleached half-life of a Monte Carlo high-rise, where they knew only two people: Princess Caroline and Karl Lagerfeld.

Starved for a wider selection of fun, they began to spend their winters at the Chateau Marmont, where they could be with half the people they knew, and meet a new cast of characters. Their friends were Timothy Leary and Arthur Janov, father of the primal scream, and artists, movie stars, comics, publishers, producers, and rich louche couples who wanted private photos.

When Helmut’s wonderfully candid autobiography came out, I reviewed it for the Los Angeles Times, and June welcomed me back into their lives. I booked a week at the Chateau Marmont to be with them again. It was January 2004.

Helmut now wore glasses with red plastic rims; June’s hair was still brown, still straight in a bob. He was 83; she was 80. They could have been my age, full of work plans and details about the imminent opening of the Helmut Newton Foundation, in Berlin. We ate lunches and dinners and caught up on years of stories.

On Friday we gathered in the Marmont garage. June was going to return their rental car, while Helmut followed in the monster white Escalade they had been loaned. He pulled out of the garage first, then June; I was behind. Suddenly everything stopped, chambermaids turned in the walkway, a waiter began to run. I got out of my car. June waved me over to her. “Come, come!”

The Escalade was embedded in the retaining wall across the narrow Marmont Lane, at a slight angle. As we reached the door, we saw Helmut’s head pressed against the steering wheel. He was immobile. June turned to me.

“Do you think this is how he died?” she asked. The future and the present became the past. She opened the Escalade door, took Helmut’s glasses off the steering wheel, and handed them to me.

A woman whose car he’d clipped on Marmont Lane stood in the road, taking pictures.

The ambulance arrived swiftly, but remained parked a long time, with Helmut in the back. June issued orders as she got into the ambulance: “Call Barbara Davis because it’s going to Cedars. Get Phil Pavel, and join me there with him.”

In a waiting room decorated with cartoon nursery figures, Phil Pavel and I sat on either side of June while a doctor told her that Helmut was dead. She listened, took a breath, rose to her feet, and asked Phil to take her back to the Marmont for her camera.

A barrier between herself and reality. Maybe that’s what talent is.

June Newton, photographer and actress, was born on June 3, 1923. She died of undisclosed causes on April 9, 2021

1. June Newton, photographed by Helmut Newton. “In Our Kitchen,” Rue Aubriot, Paris, 1972.

2. June as Joan of Arc, photographed by Helmut at the Princess Theatre, Melbourne, 1954.

3. Joan Juliet Buck, photographed by Alice Springs at the Chateau Marmont, Hollywood, 1983.

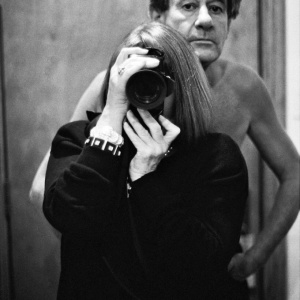

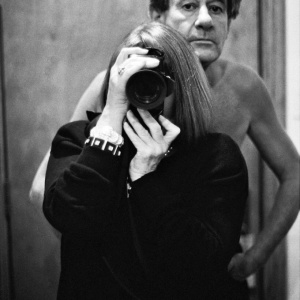

4. “Self-portrait with Helmut,” Chateau Marmont, 1991.

source | airmail.news

June Newton

Helmut Newton was “the King of Kink,” but his wife, who died at 97 in Monte Carlo, was the mastermind behind the camera

Joan Juliet Buck

In Paris, the past is present and the legends are sociable. The night in 1981 that I first met June and Helmut Newton, at their place on the Rue de l’Abbé de l’Epée, he and I immediately started arguing. I’d come to discuss a text I was supposed to write for one of his photo books, but the expat-in-Paris atmosphere of culture as pleasure was so familiar that I forgot he was a legend and 30 years my senior. I contested what he’d just said. He shouted. I shouted.

June watched with the unfazed appreciation of an actress at a noisy rehearsal, then booked a table and swept us out to a restaurant, because, as we all knew, dinner is the cornerstone of expat survival. And then we were friends for decades of dinners, collaborations, and fun shouting matches. He was Berlin-blunt, she was Melbourne-blunt, and both were like family to their friends, but ever suspicious of the gatekeepers—the editors, the clients. Our friendship collapsed when I became the gatekeeper of French Vogue, and it sprang back to life after I left.

Helmut Newton’s photos conveyed such complex sexual tension that the British press dubbed him “the King of Kink.” People speculated about his relationship with models, what his actual wife looked like, what she knew, what she didn’t know, and what there was to know. One of the sexiest photographs he ever took was of June lighting a cigarette at a dinner table, her dress pulled open to expose her breasts. Married for 56 years, citizens of the world, childless, they loved each other.

June was not an amazon like his models, but a mastermind. Small, energetic, curious, always alert to nuance and depth, primed for approaching bullsh*t, June could see below the surface; her perspicacity could run acid, with a short list of short words to use on a long list of people. Always that tension between enjoying the company of fools and hating them for being fools.

Her face was square, her mouth small, her straight brown hair in a bob. I only saw her wear clothes that were black or white, with some kind of chunky Art Deco bracelet. I didn’t know until very recently that she’d won an award for excellence in theater and played Hedda Gabler on television. “I was an actress” was as much as she said. The photos of her when she was an actress in Melbourne, stage name “June Brunelle,” show a severe expression, a tidy mouth, and the same bangs.

He called her Junie; she called him Helmie.

Their legend was set. They’d met in Melbourne, where she was an actress of 23 and he was a beginning photographer of 27, a German-Jewish refugee released from an internment camp and then from the Australian Army. They married in 1948, and she carried on acting until, and a little after, they moved to Paris in 1957; he worked for French Vogue, was discovered and then rejected by Diana Vreeland, and later re-discovered by Alex Liberman.

While shooting 45 pages for American Vogue in New York in 1971, he had a major heart attack. As he underwent one of many procedures, he photographed himself on his bed, full of tubes. “There is something about a camera,” he wrote in his 2003 autobiography. “It can act as a barrier between me and reality.”

He was too sick to work; June flew to New York, picked up his camera, and completed the assignment. She needed a pseudonym and, in the spirit of irony, chose the name of a small Australian town, Alice Springs.

By 1981, June took only portraits, and not often enough. They were extraordinary, frequently of women, and ran in Vanity Fairand Egoïste, Nicole Wisniak’s large-format black-and-white magazine. That was when a black-and-white photo shot on Tri-X film could be as potent as a thriller. The contrast between her impenetrable black and luminous whites, brought out through the silver-gelatin process by the same, often French, master printers that Helmut used, gave a unique depth and power to the faces she caught on a Pentax camera with a 50-mm. lens.

Helmut’s photos expressed a fantasy of his, a construct or a memory, and were directed, lit, and staged; posed by fashion editors, hair and makeup artists, and assistants; and commissioned by brands or magazines, principally Vogue. June’s portraits were taken in ambient light, with neither editor, nor hair, nor makeup, often for no reason other than her desire to take a picture. She proceeded from a combination of sympathy, curiosity, and respect for the imagined self-image of the subject. I asked June to take portraits of certain people I interviewed. One of the remarkable ones was Marie-Louise von Franz. June went to Küsnacht to shoot the revered 70-year-old Jungian—a small, severe, slight woman—with her bulldog drooling just behind her in the frame, more shadow side than pet.

In the 80s, anyone who posed for a magazine feature—politician, actor, artist—was dressed up in sample clothing and amended by a makeup artist to promote a fashion advertiser. June went for the person, and always caught what lay beneath the surface. I’d posed for her as a friend in 1983, in full joy on their terrace at the Chateau Marmont, wearing a T-shirt and my grandmother’s pearls, on a day when I had a secret that made me happy, and it showed. The photo wasn’t published for 34 years.

It was different when she took my portrait in 1987, to go with a magazine story for the launch of my second novel; I was so unsure whom I was trying to be that she had to do three sittings before we had the one usable picture, in which I am pretending to be Romaine Brooks. Or maybe George Sand, or maybe Ronald Firbank.

The socialist victory of François Mitterrand in 1981 scattered those expatriates who actually paid French taxes to easier systems, and that was the end of the glamorous, tasteful life on the Rue de l’Abbé de l’Epée. The Newtons went into tax exile and ended up in the bleached half-life of a Monte Carlo high-rise, where they knew only two people: Princess Caroline and Karl Lagerfeld.

Starved for a wider selection of fun, they began to spend their winters at the Chateau Marmont, where they could be with half the people they knew, and meet a new cast of characters. Their friends were Timothy Leary and Arthur Janov, father of the primal scream, and artists, movie stars, comics, publishers, producers, and rich louche couples who wanted private photos.

When Helmut’s wonderfully candid autobiography came out, I reviewed it for the Los Angeles Times, and June welcomed me back into their lives. I booked a week at the Chateau Marmont to be with them again. It was January 2004.

Helmut now wore glasses with red plastic rims; June’s hair was still brown, still straight in a bob. He was 83; she was 80. They could have been my age, full of work plans and details about the imminent opening of the Helmut Newton Foundation, in Berlin. We ate lunches and dinners and caught up on years of stories.

On Friday we gathered in the Marmont garage. June was going to return their rental car, while Helmut followed in the monster white Escalade they had been loaned. He pulled out of the garage first, then June; I was behind. Suddenly everything stopped, chambermaids turned in the walkway, a waiter began to run. I got out of my car. June waved me over to her. “Come, come!”

The Escalade was embedded in the retaining wall across the narrow Marmont Lane, at a slight angle. As we reached the door, we saw Helmut’s head pressed against the steering wheel. He was immobile. June turned to me.

“Do you think this is how he died?” she asked. The future and the present became the past. She opened the Escalade door, took Helmut’s glasses off the steering wheel, and handed them to me.

A woman whose car he’d clipped on Marmont Lane stood in the road, taking pictures.

The ambulance arrived swiftly, but remained parked a long time, with Helmut in the back. June issued orders as she got into the ambulance: “Call Barbara Davis because it’s going to Cedars. Get Phil Pavel, and join me there with him.”

In a waiting room decorated with cartoon nursery figures, Phil Pavel and I sat on either side of June while a doctor told her that Helmut was dead. She listened, took a breath, rose to her feet, and asked Phil to take her back to the Marmont for her camera.

A barrier between herself and reality. Maybe that’s what talent is.

June Newton, photographer and actress, was born on June 3, 1923. She died of undisclosed causes on April 9, 2021

1. June Newton, photographed by Helmut Newton. “In Our Kitchen,” Rue Aubriot, Paris, 1972.

2. June as Joan of Arc, photographed by Helmut at the Princess Theatre, Melbourne, 1954.

3. Joan Juliet Buck, photographed by Alice Springs at the Chateau Marmont, Hollywood, 1983.

4. “Self-portrait with Helmut,” Chateau Marmont, 1991.

source | airmail.news

Benn98

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 6, 2014

- Messages

- 42,582

- Reaction score

- 20,803

JJB is in top form as usual. One of my favourite fashion writers yet. It's not just her insider's insight. Glad she still has a platform after Vogue pretty much ruined her career.

But I'm seriously wondering to what extent June's short stint influenced his work creatively or vice versa because there are defintely some crossover elements. Hope it's not like that movie, The Wife with Glenn Close.

Because the idea of ownership is so real nowadays and it's very easy for someone to be robbed of credit. I see it nearly every day in the office when a good idea gets praised without giving credit to the person who came up with it or just chalking it down to 'teamwork'.

But I'm seriously wondering to what extent June's short stint influenced his work creatively or vice versa because there are defintely some crossover elements. Hope it's not like that movie, The Wife with Glenn Close.

Because the idea of ownership is so real nowadays and it's very easy for someone to be robbed of credit. I see it nearly every day in the office when a good idea gets praised without giving credit to the person who came up with it or just chalking it down to 'teamwork'.

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,687

- Reaction score

- 5,329

^This article is more riveting than most movies, what a shocking ending!

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 26

- Views

- 9K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)