May 12, 2010, 2:50 pm

Q & A: Joerg Koch

By Cathy Horyn

After reading the summer issue of 032c, featuring William T. Vollmann and photographs by Danko Steiner, I rooted out my few copies of Nest. I hadn’t thought about them in awhile and wasn’t surprised that their look and sense of freedom continued to inspire. A frustration voiced a lot these days — by art directors, writers, bloggers and others — is that people aren’t actually creating new things today. They are repeating, mimicking, collecting, downloading, endlessly commenting upon — activities that may be interesting and which may reflect the present moment but which are not about creating anything. One could even argue that they are the opposite of creativity and produce the feeling of being in a prison. Of course, when you consider the very real problems that many people in the world face, like hunger and shortages of medicine, these sorts of complaints sound silly. But creativity in the arts and in applied arts like fashion obviously does matter, and the ways that people insist on being outside the prison are interesting. Perhaps that was the essence of my conversation with Joerg Koch, the editor of 032c, which is based in Berlin. Here are some excerpts:

Q: Reaction on blogs can be something of a mixed bag.

A: We get completely trashed in those Internet discussion boards.

Q: You do?

A: Oh, absolutely. The stuff we do is often quite polarizing and often made for a specific context. Then suddenly a thing is taken out of that context and people assume that it’s made for everybody but it’s not. We get some ferocious comments. People are extremely opinionated.

Q: But are they informed?

A: It’s a mixture of being half-informed. They’re not really connected or they’ve become very orthodox in their views and don’t accept other viewpoints.

Q: Are you stimulated by Web sites?

A: The Internet is exciting for us but it’s completely different from what we want to achieve with the magazine. I think there is simply too much noise on the ‘net. You don’t have the precision or impact that you have with a print magazine. It’s a challenge for us. Our Web site is completely targeted to the search engines. I don’t think there is a sense with loyalty on the Web. Most readers will come to your site randomly and disappear after clicking five or so pages. [032c plans to introduce a new site soon, with access to its archive and then will add more resources.] But it’s not like a magazine; a magazine tries to create an atmosphere, it tries to create an identification. All these elements are not possible on the Net.

Niche magazines are not really affected by the crisis and the general lack of confidence in print. Even though 032c started very old-school, on newsprint, we always perceived it as a post-Internet magazine. The rhythm of a biannual publication works perfectly for us. You have the time for distribution. It’s really crazy how long it takes to get the magazine onto newsstands. In New York, the new issue is surely not on the newsstand yet, even though it’s been out in Germany for two weeks.

In the long term, we will have difficulty having enough sales outlets. Mainstream magazines are not selling enough copies, so newsstands are failing. In London, for instance, Borders closed and that was a major outlet for us. To me the structural elements are more worrisome than the content of the magazine or advertising.

Q: How did the Vollmann story come about?

A: It started with a small text I read in The New York Times. Then I simply researched Vollmann, and everything I read intrigued me to do that dossier. That’s essentially how 032c operates. That hasn’t changed from issue one. It’s about having this curiosity or an interest in research. Now, obviously, the magazine is much more ambitious—ambitious in the commercial sense. At one point we reached a level where we had to say, ‘Are we actually going to take this seriously as a business?’ That means advertising meetings and trying to sell the magazine to people who really don’t care about William T. Vollmann or the ideas being featured in the magazine, but still trying to get their money. And making the magazine understandable and relevant to a certain group of people.

Q: How does that affect the story choices?

A: The mix got even more extreme. With magazines, I feel there isn’t that much beyond the mainstream these days. Everything that pretends to be underground seems to me quite regressive or like a nostalgic project. I think 032c might come from an underground sensibility but it really tries to get into the mainstream—like pretending to be the next generation Vanity Fair. With that silly megalomaniacal drive. That’s what I mean by ambitious. You make really big stories like 40 pages on Vollmann, or on Thomas Demand in the past.

Probably the idea of Vanity Fair was influential for us — the idea of running a story of 15 pages, then some war reportage, and having a bikini-clad girl in the mix. I don’t think the aesthetic of the 032c has been shaped by other magazine so much as it has by architecture or certain word concepts. For instance, industrial designers talk about the performance of an object. If you apply that idea to a magazine, it suddenly opens up a lot of doors, at least for us. These are more abstract terms. In the beginning it was very productive for the magazine to be based in Berlin. You don’t have money but you have time. And you have time to make mistakes and do research. If you’re based in New York or London, you don’t really have much time to mess around with. You have to speed up the process by doing lots of referencing in order to move quickly ahead. And you can see it in the product. It’s like a density of ideas chopped off and added onto.

Q: Many indie magazines quickly become predictable.

A: They’re creating another prison. I think there’s misconception that if you want to understand the times we live in you have to only feature the stuff that happens right now, around you. You have to feature Lady Gaga or Dolce & Gabbana in their holiday home to understand the world. But, again, because of the biannual rhythm, it’s so much more productive to be slightly detached from what’s happening. You have more flexibility and a more abstract view point of what’s happening.

Q: Let’s talk about covering fashion.

A: How to report on fashion hasn’t really changed at all. That whole system is so rotten, no? The idea of collections just doesn’t make sense any more. But nobody knows what to do. We never had fashion shoots until issue nine or 10. I came to fashion via Helmut Lang, Raf Simons and Hedi Slimane. They had a reference system that I could relate to. From that point of view it progressed. And with the fashion, I think it’s a love-hate relationship. When you asked me how the magazine changed, it also means that I go to the shows. Obviously I don’t have to be there, but if you want to show commitment to the houses you really have to show up and do all that social stuff. It helps commercially and that’s completely valid. For me, it’s the same as going to the Frieze Art Fair. You meet tons of people and things can happen. But it rarely happens that because of a collection we decide to do a certain story.

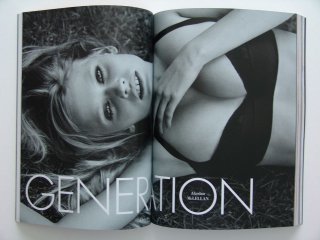

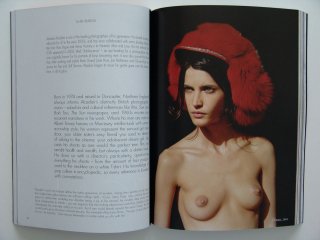

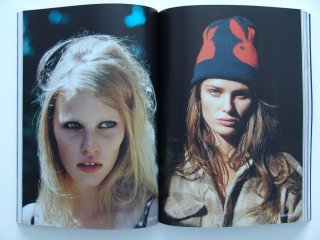

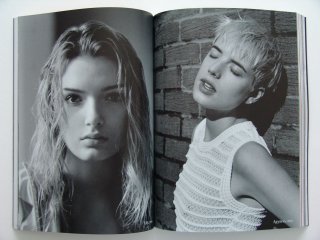

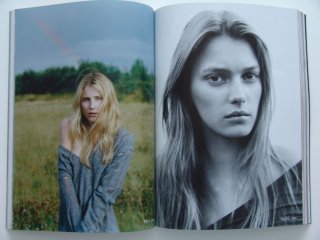

Q: I liked the Danko Steiner series. How did that come about?

A: When Danko was still the design director at American Vogue, he sent me pictures, like eight or nine, which were quite out there, and he asked if we would be interested in collaborating. I said, “You have to make the picture even more extreme. Push it harder.” That was in the last issue, and we were thinking of making it a trilogy, so this is like the second installment in the current issue.

They have been polarizing. People either love them or completely hate them. And that’s terrific. It means we’ve engaged the reader, and too many magazines today are middle of the road. 032c should be surprising you but it should also be identifiable. You should know what to expect. The Danko Steiner story is very appropriate. It has all these top models, but they look completely different.

Q: It’s the sort of energy and perspective you want to see in a regular fashion magazine.

A: After the first story, all the other magazines flocked to him and said, “Oh, we really want to have exactly the same story.” That’s how they operate! It just doesn’t make sense.

If we were doing the magazine without any fashion stories, life would be super easy. Seriously. You can’t imagine. The magazine would run on auto-pilot. It would be a pleasure to produce.

Q: Why does fashion make it difficult?

A: It’s the people in the industry. I don’t think you will ever meet so many unhappy people. People in the fashion industry are really contaminated with bad habits. A certain human kindness evaporates once you make a career in fashion. In the beginning you’re really treated badly and then you seem to get accustomed to it. As a magazine we are in a privileged situation. Really great people work with us and we have a good reputation, so we don’t have any problems getting the clothes we want or the models. It’s more of a general observation. It’s really hard to make a difference with fashion stories—to come up with ideas that differentiate us from fashion magazines. And I don’t think we are successful at this yet. With Danko’s stories and certain others, yes. The reaction you get form a Vollmann or a Cy Twombly piece is so much stronger than you get from a fashion shoot.

Q: Is there a story you would love to do, that’s a bit of a dream?

A: The next issue is our 20th. Pitti Immagine has invited us to do a big exhibition in January and we’ve been thinking about doing something on Germany. It’s very unclear but the starting point is a commercial, an advertisement for Prada done by Ridley Scott’s daughter. Have you seen it? As strange as it sounds, it’s the most enticing future perspective of Berlin. It’s like a complete distortion of time — ’50s jazz with contemporary Berlin — and everything crisscrossing.