Frock of the New

It is hard to believe that it is 100 years since Mr Dior was born. In this house, and to me, he is still very much present.' So says John Galliano on the eve of the opening of an exhibition celebrating the centenary of the couturier Christian Dior's birth. Then, and on characteristically purple form: 'I wish I could have met him. I think we would have had a lot in common: our love of nature and beauty and, above all, the desire to make women blossom like flowers. He planted great roots and I am honoured to be nurturing and tending to his blooms and cutting fresh buds every season.'

Galliano, today the creative force behind what has become France's most famous status label, is right to compare Dior's talent with his own. Like his predecessor, the designer thrives on fantasy and escapism over and above creating clothing that mirrors the anxieties of the time. Neither is Galliano overly litist in his approach. Such things are relative, clearly, but the high-impact, even mainstream appeal of a global fragrance campaign, for example, appears to thrill him almost as much as working on that most exclusive of beasts: the twice-yearly haute couture collection that is the jewel in any French fashion brand's crown. Dior felt that way too. Most importantly, Galliano, like Dior in his heyday, looks unashamedly to the past for inspiration, the re-working of the bias- cut gowns of the 1930s to suit more modern women's needs still being the younger designer's best-known contribution to date.

This latter point resonates particularly because one of the great ironies of fashion history is that Dior's New Look, let loose on the world on 12 February 1947, wasn't actually new at all. Instead, it was proudly nostalgic " or, to use the more contemporary fashion lexicon, retro. 'I do admit that if I had been asked about my work and what I hoped to achieve on the eve of my first collection, the one that launched the New Look,' Dior once said, 'I certainly would not have talked about a revolution. I could never have foreseen the reception it was about to receive.' That reception " and never has a humble clothing collection, haute couture or otherwise, had such impact " was all in the timing.

Throughout the Second World War, the strict rationing of fabric meant that clothing was dour to say the very least. Dior's somewhat melodramatic biographer, Marie-France Pochna, describes the appearance of French women at the time thus: 'Everything about their attire spelled misery, suffering and sham " clunky shoes with cork wedge heels, a false stocking seam drawn skilfully on to the leg, short skirts (there was no material to spare) with a split (to make for easier pedalling), and on top of it all a harsh, square cut jacket.' A yearning for a more frivolous outlook was expressed in the f headwear of the day which was, by contrast, whimsical to the point of folly. This did not, of course, go unnoticed by Dior who, following a spell at Robert Piguet, was working for society couturier Lucien Lelong. 'Made up of remnants that could serve no other useful purpose, they looked like enormous pouffes,' he observed, 'flying in the face of the all-pervading misery ... And common sense.'

However absurd, such headwear identified a need. What's more, French fashion in the broader sense was suffering too. Undermined by Germany (it is the stuff of fashion legend that the Third Reich attempted to move the entire haute couture to Berlin), America (hell- bent on the democratisation of the industry as exemplified by the chic and simple work of Claire McCardell and her contemporaries) and Italy (under Mussolini, attempting to establish itself as at the forefront of world style) the Paris ateliers urgently required an injection of new blood. The hitherto unassuming, bespectacled man from Granville, Normandy, was quick to step into the breech, making it his mission to restore the haute couture to its former, hugely extravagant glory.

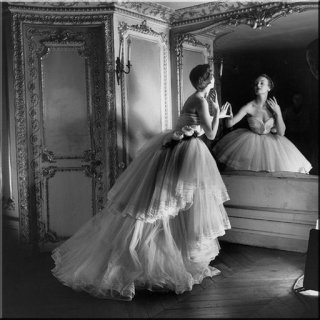

In his newly opened salon at 30 Avenue Montaigne, just a stone's throw from couture's other big names, Dior took to the stage. The collection that launched his solo career featured hats so wide they would barely fit through the door, soft-shouldered and wasp-waisted jackets that emphasised the bosom, flagrantly eroticising the female form in a way that hadn't been seen since the Belle Epoque. Most extreme was the 'corolla' line skirt, comprising no less than 20 metres of fabric. Dresses up until that time had been restricted to no more than three, and flew in the face of the establishment in a manner so politically incorrect it took the breath away. 'It's quite a revolution, dear Christian,' said Carmel Snow, editor of Harper's Bazaar who was among the privileged few in attendance, before going on to unwittingly christen the style: 'Your dresses have such a new look.'

Unsurprisingly, while Paris's upper echelons saw the New Look as just the influx of the happy luxury they had been waiting for, not everyone was so amused. The serpent-tongued modernist Coco Chanel described her contemporary as a 'madman' for putting women back into corsets. On the streets of the French fashion capital, the less privileged famously attacked those wealthy enough to buy Dior's designs, literally ripping the clothes off their backs as they walked. Once the New Look hit American soil, resistance was its most fierce. Consider the fate of one Louise Horn of Louisville, Georgia, who had the unfortunate experience of catching her new skirt in the automatic doors of a bus. She found herself being dragged for a whole block before the vehicle came to a stop and, as the first recorded victim of the infamous style, she vowed not to let the matter rest, immediately setting up an anti-Dior petition which 1,265 other women dutifully signed. They called themselves The Just Below The Knee Club in protest at Dior's longer-than-average skirt.

Despite its detractors, however, the New Look took hold. For the majority of women its retrospective gaiety was hugely desirable. And Dior was more than man enough to rise to the challenge of ensuring his designs translate for a broader audience as faithfully as possible, all while making a tidy profit for the house. Instead of allowing his work to be copied, he sold his designs worldwide and for mass manufacture. In England, John Lewis's House Gazette reported on a fashion show staged by the store to show their customers how the New Look might be worn. 'Miss Rowland, smiling more than ever, held up an enchanting little corset, pink satin and lace, which she assured us must be faced by all as the necessary foundation for the smart figure. The little garment was then girded on to a slim model with such vigour that the blood rushed to her face, while Miss Rowland exhorted her to greater efforts. 'Pull yourself in a little dear' and we all held our breaths in sympathy.'

By December 1947, the New Look had well and truly hit the mainstream, appearing in US department store Orbach for the not entirely princely sum of $8.95 for a dress. It sold in its millions. Two years later, 75 per cent of all French fashion exports bore Dior labels. As well as selling his womenwear designs, Dior launched Miss Dior, the fragrance, and oversaw the launch of Christian Dior hosiery and silk ties. It is perhaps no coincidence that, at the time Dior opened the doors of his eponymous haute couture salon, Pierre Cardin " soon to become the most overly licensed designer in fashion history, signing his name across everything from notebooks to cooker hoods " was his head of tailoring. And Dior was also the first to identify the genius of the young Yves Saint Laurent.

Christian Dior died suddenly in Italy on 29 October 1957. He was 52. It is testimony to the hold he had over French culture that, in response, the French capital was overrun by flowers. The sheer volume of tributes " bouquets of hawthorns, carnations, camellias, tuberoses and, of course, his favourite lily of the valley " was such that the government authorised them to be placed at the foot of the Arc de Triomphe. It almost goes without saying that this, even in a city that treats fashion with a greater respect than most, was unprecedented.

Saint Laurent " in Dior's own eyes, his natural successor " was to step into his shoes for no more than a year. The fledgling couturier's designs were deemed too radical, in the end, for a house that had by then become a brand. Upholding the Dior name, which prized itself on drawing from tradition, was worth millions and the young maverick designer was unceremoniously sacked. Marc Bohan, also employed by Dior, took over, ensuring the well-mannered continuity of the name for many years. Today, John Galliano is responsible for the label, staging shows so elaborate and over-the-top that they might have made even the wildly extravagant Dior himself blush.

'To see a collection of Dior dresses filing past gives one the pleasure of watching a romantic and spectacular pageant,' the photographer Cecil Beaton wrote of Christian Dior in his prime " the photographer took Princess Margaret's portrait wearing Dior on the occasion of her engagement. 'With an impeccable taste, a highly civilised sensitivity and a respect for tradition that shows itself in a predilection for the half-forgotten, Dior creates a brilliant nostalgia.'

Conservatism in fashion has never seemed so radical before or since.