My Passion for Cashin: A Young Student Remembers Her Fashion Mentor, by Stephanie Day Iverson

When I met Bonnie Cashin nearly four years ago, I wore my first Cashin -- a turquoise leather coat that was designed in 1974, one year and a spring collection after I was born. The coat was the reason that Bonnie and I were meeting. I fell in love with its matching silk crepe lining and hip-height encirclement of pockets, designed for carrying books, the first day I saw it in the Sotheby's fashion department, where I worked as a researcher. I was also working on my M.A. at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, Design and Culture. Reading about Bonnie (who died in 2000 at the age of 84) and finding that little had been published about her nearly seven decades of costume and clothing design, I wanted her to be the subject of my thesis.

No one bid on the coat, and it was purchased for me as a surprise thank-you by my boss, Tiffany Dubin. Soon afterward, it was singled out in one post-auction review as a "tired" fashion that we made a mistake in trying to sell. (This, regarding a garment that has since elicited thoughtful compliments from jaded teenage boys in the midst of after-school reigns of terror on the subway.) When I voiced my interest in Bonnie, a chain of mutual friends managed an invitation for me to phone her. In a somewhat lengthy, lofty monologue, I told her about the coat and how I felt destined to redress historical neglect and contemporary misunderstanding and that it was critical that her creative life be documented and examined in its entirety! When I finished my speech, there was silence. Then laughter. She essentially told me to settle down and asked if I would like to join her for tea at her apartment.

Bonnie and I just clicked. Soon after our first meeting, we slipped into a teasing, loving, sisterly relationship. She called me Dodo or referred to me as "the big question mark." She also granted me exclusive and unrestricted access to her design archive, housed in a separate apartment below her residential space at United Nations Plaza. I would ring her bell and hear her sing, "Yoo-hoo, yoo-hoo, Stephanie," as she approached the door. We would give each other a quick peck, after which she would hand me the key to the archive and say, "See you later, kiddo."

My ongoing research in her studio is a zigzag treasure hunt through material pinned across bulletin boards, arranged around slide carousels, piled under and over tables and collected in baskets, portfolios, file cabinets, travel journals and closets. I plan to spend the next two years here finishing a book on Cashin. Among her gems, I've found her childhood sketches of annotated dance costumes and fashions -- filled in with colored pencils or watercolors -- showing the combined influences of her custom-dress maker mother, fashion magazines, fairy tales, ballet performances and a fascination with the Chinatowns of Los Angeles and San Francisco that filled her nomadic California childhood. Stacks of black-and-white photographs of smiling, sexy-but-sweet chorus girls are all that remain of Bonnie's first career as a dance costume designer for Fanchon & Marco, a troupe of line dancers, when she was 15 and still in high school and had to be driven to work in Los Angeles every night by her mother. The record of her late-1930's entry into ready-to-wear is in fashion spreads that Bonnie cut out from Vogue and Harper's Bazaar and pasted into floral-fabric-covered scrapbooks. She marked with small red-pencil checks the ensembles she "anonymously" designed. Articles from the war years explain Bonnie's appointments, first as a designer of Civilian Defense uniforms and then as one of 10 designers representing the best of American fashion in The New York Times's first-ever Fashions of The Times.

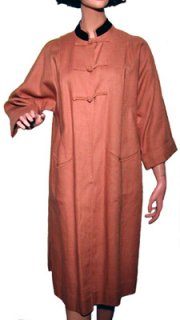

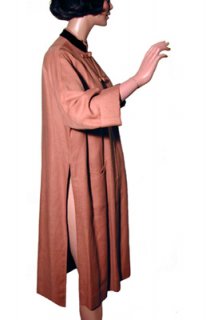

From her 1943-1949 tenure as a designer in the "glamour division" at 20th Century Fox, there are portfolios of oversize watercolor and ink illustrations, many labeled for a particular actress's on- or offscreen wardrobe, all foreshadowing the "real" clothing designs for which she would become most famous. From her decades in ready-to-wear, thick books of editorial commentary and annotated fashion sketches demonstrate how to layer tweed ponchos and suede Persian tunics, mohair Noh coats, funnel-necked cashmere sweaters and wool-jersey, leather-trimmed dresses, examples of which still hang in pink, orange and green closets.

She designed the clothes that she wanted and needed to wear for own modern, mobile, madcap lifestyle. A letter dashed off to her mother tells of a decision to "skip Amsterdam, it will always be there" in favor of traveling "to Russia, on a ship which stops briefly in Copenhagen and Stockholm and lands at Leningrad -- 4 days there -- then by train to Moscow. I'll fly from Moscow to London, then home. It sounds like a lark." Days later, a postcard teases: "Guess where we are -- extraordinary -- fabulous -- unbelievable -- feel wonderful. Approaching the glorious U.S.S.R. -- and about to be approached by the glorious custom officers who've just come aboard." Next, back in London, "went to the opening of 'Othello' at Covent Garden Opera . . . went to Ascot to the races Friday -- sunny wonderful day -- all the ladies in their big hats -- saw that Queen and her whole party close . . . have seen some good plays. Liberty is planning a Bonnie Cashin department -- all Sills things - . . . met a man from Lyle of Scott -- the cashmere sweater place -- Dior used to do a line for them and they might be interested in me doing something. I hope so -- I would like that."

As I sifted through Bonnie's past, curled up on her Nelson Marshmallow sofa or perched at her drafting table, Bonnie would pop down to "play" with stacks of fabric or occasionally, to my consternation, to weed through her piles and files of papers. As soon as I heard her tearing up documents, I would raise my head and demand to know what she was erasing from history. I was a constant interruption, incessantly pointing at things and asking just a "quick question." After learning "where on earth" I found something, she would tell me about relying on her mother to help her sew all night in order to meet a costume deadline for the Roxyettes, the precision dancers at New York's Roxy Theatre who were rivals of the Rockettes, or about a cocktail party at which she and Gypsy Rose Lee lounged in matching fur skirts that Bonnie had originally designed for Gene Tierney in "Laura."

We often chatted upstairs at her massive marble and iron table, seated on weightless wire garden chairs. We looked out over the U.N. or at the little island in the East River where she and Buckminster Fuller envisioned erecting a torch whose height would change according to the intensity of international conflicts. Subjects ranged from lamenting Seventh Avenue's aesthetic in-breeding to Bonnie's hope that I would date one of her "younger" friends. In the last year of her life, these afternoons became planning sessions. Word that I was culling information for a book on Bonnie had led to an invitation to co-curate a retrospective (held last September) of her career at the Fashion Institute of Technology with Dorothy Twining Globus, then its director.

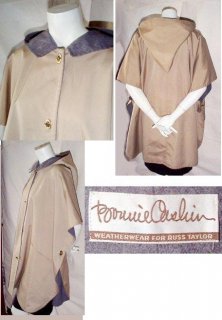

Bonnie wanted this show to convey her design philosophy, best summed up in what she referred to as "a little ditty" by the Grateful Dead, pinned up over her desk, that advised "once in a while you get shown the light in the strangest places if you look at it right." Bonnie firmly believed that accepted practices and intended uses were not sacred. Metal toggles on the convertible top of her little red sports car became closures on the handbags she designed for Coach and dog-leash clasps allowed her to hitch up long skirts and carry cocktails up the stairs of her country house. Car blankets inspired her first ponchos, and upholstery fabric, leather and suede were her favorite materials for evening dress.

After seeing the show, one group of students commented that the clothes were wonderful but were just like what everyone sees every day. While missing the point that Bonnie was the originator of these familiar ideas and "looks," their summation attests to her unrecognized but tremendous influence today. Bonnie believed that she designed for her contemporary moment and disagreed that she was ahead of it. Such observations, she claimed, were really comments on the lack of innovation in current fashion. But the reality is that she was so avant-garde that her work of 25 or even 50 years ago seems reflective of our own time.

...my memory isn't what it used to be

...my memory isn't what it used to be

The colors of her designs in winter would be such a relief in a grey city.

The colors of her designs in winter would be such a relief in a grey city.