Rudi to Wear - A retrospective of legendary fashion designer Rudi Gernreich makes its only U.S. stop at ICA.

Rouse yourself, Weintraub! The miniskirt is back!" exults a park bench geezer to his companion in a recent Booth New Yorker cartoon. The object of his pop-eyed gaze wears a Rudi Gernreichian outfit consisting of two narrow bands of patterned fabric.

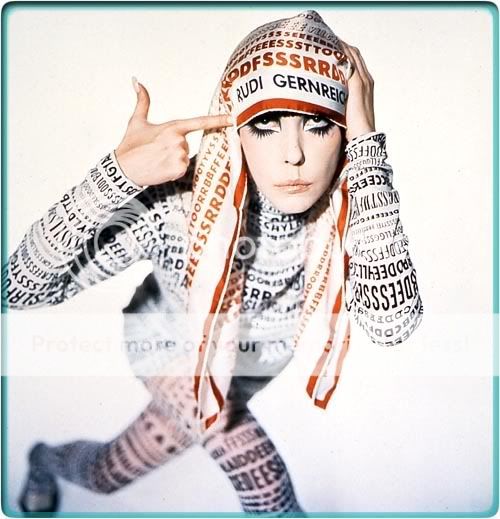

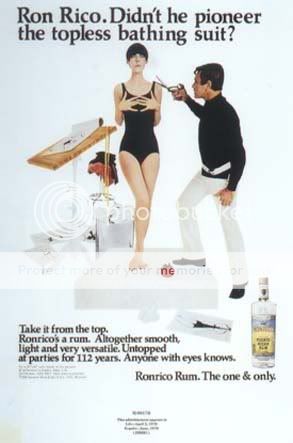

I wonder if Gernreich (1922-1985) would have appropriated this gem for his scrapbooks. Selected reproductions of the Los Angeles designer’s clippings, with headlines like "Bare Bosoms" and "Rudi macht dich frei!" (Rudi makes you free!), paper the high walls and floor of the ICA’s tribute, "Fashion Will Go Out of Fashion," an exhibition that is simultaneously sociology lesson and itself a work of art.

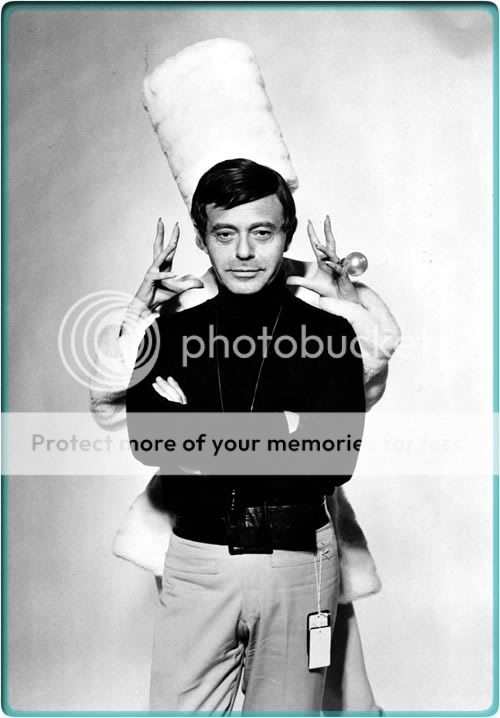

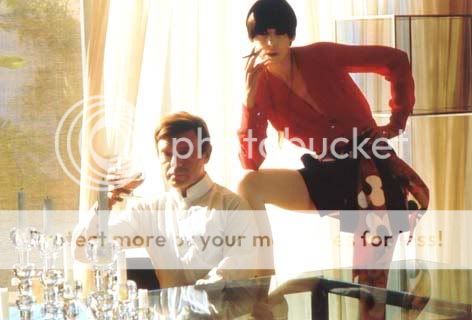

Rudi! rudi! Gernreich poses with his model and muse, Peggy Moffitt, in 1968.

Nearly a half-century after the inventor of "unisex" fashion used mass-market style to skewer couture elitism and ladylike "good taste," his miniskirt again arouses controversy and lust on the streets and in the news media. Its reappraisal is ripe for the art gallery. Originating at Künstlerhaus Graz in Gernreich’s native Vienna, the elaborately staged show has its only U.S. showing here. It speaks to several leading issues in the contemporary context.

First, consider the vogue for clothing design in high-art venues. Responding to recent shows like the Guggenheim’s Armani and the Metropolitan Museum’s "Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years," Roberta Smith, in The New York Times last year, questions the validity of "exhibitions that look like upscale stores, or exhibitions that look like historical society displays." She goes on to suggest bitterly that, "since a majority of Americans don’t like art, the logic seems to run, it must be the museum’s job to give them something else," adding that such exhibitions revamp the cliché: "I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like to wear."

Given that "Fashion Will Go" is better produced and considerably more intelligent than the embarrassing Armani self-congratulation, it does seem to be more about social history than art, and its sponsorship is linked to the upscale retail store Joseph Magnin. Nevertheless, curator Brigitte Felderer’s nicely reasoned catalog essay makes a convincing case for Gernreich as the instigator of a dynamic new aesthetic that infiltrated and molded attitudes toward art and the self in the 1960s and ’70s. Gernreich was, she says, more an "artist of the avant-garde than…a fashion designer."

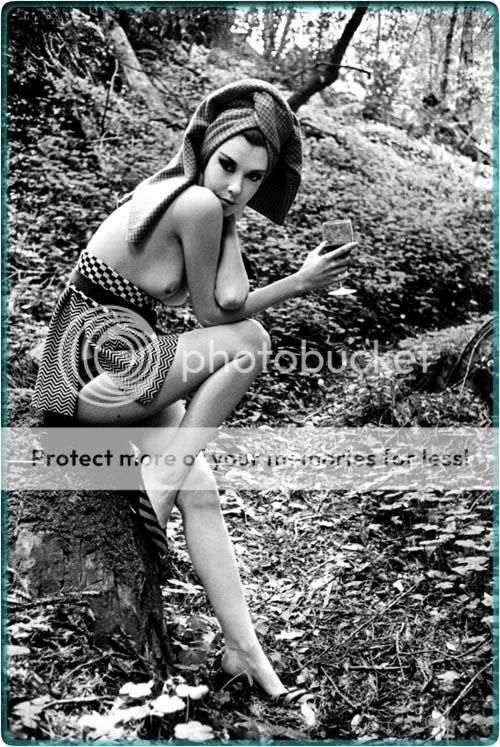

Gernreich’s clothes embody the aspirations and contradictions of his day, especially regarding the role of women as increasingly independent individuals. His knitted fabrics and daringly skimpy cuts emphasized the uniqueness of the individual human body and its movements. Many are reminiscent of a dancer’s practice clothes, not surprising for a designer who worked as a professional dancer and designed his first costumes for dance.

In 1938 at the age of 16, Gernreich and his mother arrived in Los Angeles, Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi oppression. A poor student, Gernreich fell in love with modern dance while working as an usher at a Martha Graham performance. He joined the Lester Horton company in 1942. Gernreich’s first real design success came with bold Pop Art-related fabric patterns and color combinations he created for Hoffman California Fabrics.

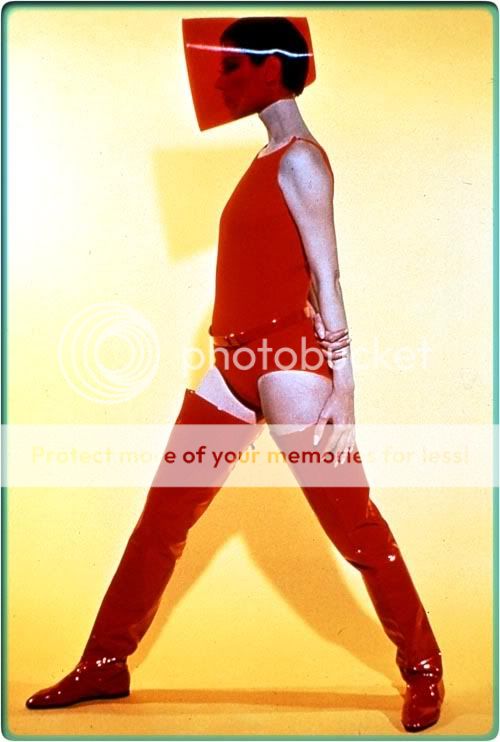

Moffitt models Gernreich’s famed monokini in 1964

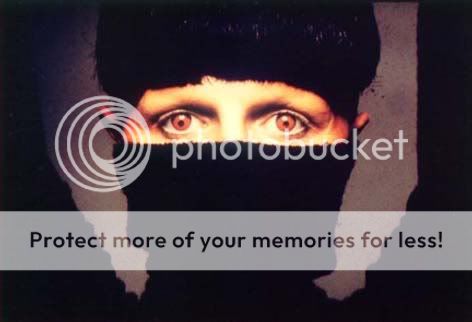

If today we are blasé about clinging, stretchy fabrics, it’s largely because Gernreich showed us how to wear them, though he probably never imagined that a thong, one of his inventions, would provoke historic shenanigans in the Oval Office. Gernreich designs tend to be reductive. "I consider designing today more a matter of editing than designing," he said in 1972. His favorite models, Peggy Moffitt, who will attend the opening reception (see interview), and Léon Bing were not muscular, but lithe and devoid of fat, while Carol Doda, famous solely for the magnitude of her enlarged breasts, also posed in a Gernreich monokini.

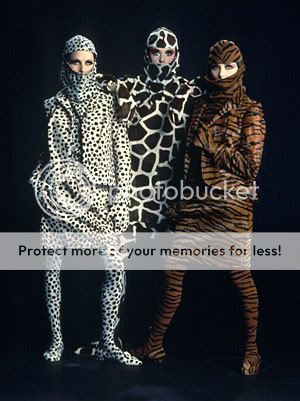

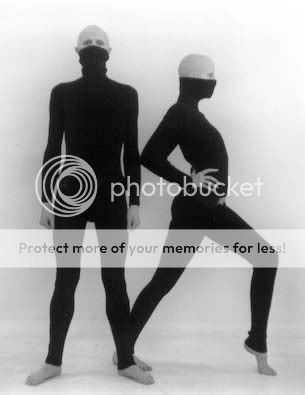

That one-piece topless bathing suit intended to be worn by men or women who had shaved off all head and body hair was the centerpiece of Gernreich’s famous UNISEX Project. Felderer points out that photographs of models wearing this costume tend to preserve gender roles through pose (for example, man standing, woman at his feet) and to eroticize the breast. Felderer claims that Gernreich postulated a "new interpretation" of the breast.

Androgyny is not asexuality. It often has a quality of intentional eroticism. By suggesting that gender taboos were arbitrary, Gernreich’s UNISEX Project implicitly challenged basic social assumptions. It may reflect his amused critique of a rigidly heterosexual society. Although in 1950 he was one of seven founders of the Mattachine Society, one of the first gay rights organizations, Gernreich was never open about his homosexuality. He called his UNISEX clothing "an anonymous sort of uniform of an indefinite revolutionary cast."

Visitors to the ICA will quickly realize that although Gernreich is the subject — and more than 125 examples of his clothing are displayed on elegant attenuated Schläppi mannequins — the exhibition design trumps the fashions. ICA preparator Clint Takeda has effectively translated the celebratory environment created by Viennese architectural firm Coop Himmelb(l)au for the show’s first venue.

Toy airplanes circling overhead reinforce Gernreich’s love of technology. A blue room with reflective water elements frames 20 daring swimsuits. A twisting "Media Tower" presents videos of Gernreich walking and talking about his work. Perhaps the most ambitious piece is a "Virtual Catwalk" video projection by media artist Daniel Egg. In this multi-element installation, reflected projections almost assume the reality of actual models posing and being photographed.

By organizing this show, Neue Galerie seems to claim Gernreich as a native son of Vienna, though he spent all but the first 16 years of his life as an American citizen. His exaggerated simplicity might well be linked to Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstätte’s commitment to simple (sometimes) affordable design. But in his use of inexpensive industrial fabrics and new attitude toward the body, Gernreich is more of a provocateur even than the reform-minded Werkstätte.

Like his contemporary Andy Warhol, he constructed a media persona and promoted himself as a product, one which remains viable at the ICA today. Even Gernreich’s pronouncement, "Fashion will go out of fashion," embodies the contradictions he loved.