-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Don't Try This In Vogue

- Thread starter model_mom

- Start date

foxinthesnow

Member

- Joined

- Feb 19, 2003

- Messages

- 561

- Reaction score

- 0

Don't Try This in Vogue

By RUTH LA FERLA

Published: September 12, 2004

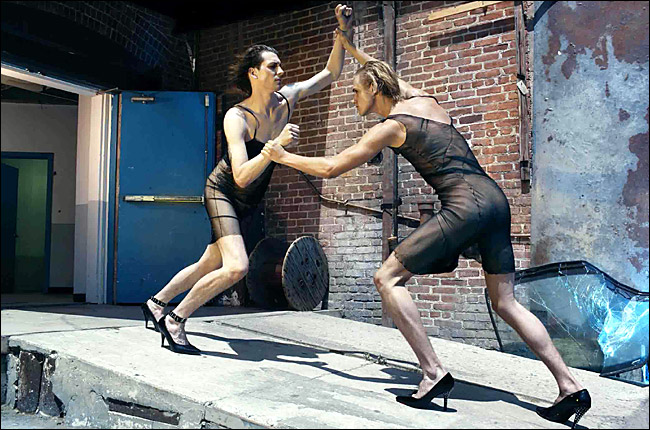

HE dress is a near-sheer sheath of silk as fragile as cicada wings, its material stretched improbably over a moderately hairy male chest. It appears in a series of brooding, sexually ambiguous vignettes conceived by Steven Meisel, who makes his photographic debut in W magazine on Monday, with a cover article coyly titled "ASexual Revolution."

On its surface, Mr. Meisel's exercise in gender-bending seems a calculated affront to middle-of-the-road sensibilities, one that Dennis Freedman, the creative director of W, hopes will grab the attention of the fashion world. "Next week under the tents, people will be talking about it," he said. "That may be all they're talking about."

Maybe so. In the hothouse of Fashion Week, the W cinematic photo essay, with its loose-limbed, nearly nude androgynous boys and girls engaged in obvious sexual play, is likely to make waves. But the photographs' impact, at least among fashion people, will have less to do with their content than with their context.

Until now, this kind of subversive subject matter, ostensibly exhibiting the latest styles, has been the province of small independent magazines and European glossies, particularly Italian Vogue, Mr. Meisel's primary outlet. And although W has long been the most adventurous of mainstream American fashion magazines in imagery, it has never published anything so sexually candid.

In fact, the new W photographs are part of a tradition that extends at least as far back as the 1970's, to art house films like "The Damned" and "The Night Porter" and to the demimonde evoked by Helmut Newton, whose perversely erotic photographs have been more than ever in the public eye since his death in a car crash last winter.

And Mr. Meisel's images are arguably no more provocative than those of music videos like "Toxic," in which Britney Spears couples with a stranger in an airplane toilet; or quasi-mainstream television fare like "Six Feet Under," which has trained its camera on the twilight world of gay dance clubs, where sweaty revelers gyrate and grope one another; or ad campaigns like one from Gucci, in which half-dressed models appear to be caught in flagrante by an unseen security camera.

Mr. Freedman knows that these pictures reflect imagery already common in popular culture and may not shock many of his readers. "These photos were not meant to be provocative, at least not in any obvious sense," he said. "What this really is about is the need of magazines to stop second-guessing advertisers and the public, and address the same issues that have long been addressed in music videos, on television and in cinema. For us to stay relevant, we must stay in touch with the rest of the culture."

This kind of relevance has given independent fashion magazines like Surface, Black Book and Flaunt a market niche all to themselves, said Ava Seave, a magazine analyst and the principal of the consulting firm Quantum Media. "They have been stealing ads and circulation from the mass publications, partly because they are not beholden to advertisers in the same way," Ms. Seave said. "They've made their mark by being graphically aggressive — that doesn't always mean sexy, just not predictable."

Ms. Seave added that readers and advertisers may be particularly open to controversial imagery at a time when magazines that resemble shopping catalogs, like Lucky, Cargo and the new Vitals, are flooding the market, dispensing with artistic ambitions in favor of bald displays of the goods.

The proliferation of such magazines runs the risk of boring readers, she said, adding, "A reader might well ask herself, `If it looks like a catalog, why am I paying for it?' "

And W itself has enjoyed success with photography that is more adventurous than that of its main competitors, Vogue and Harper's Bazaar. In the recent past, W has published photographs of Brad Pitt in the buff and the model Jessica Miller opening her raincoat to flash a breast. This year, the magazine's advertising pages totaled 1,635, a 98 percent increase over the year before. In September, W carried 434 advertising pages, second only to Vogue, with 647.

Just the same, publishing Mr. Meisel's overtly homoerotic portfolio is not without its hazards. "They're pushing it," said Reed Phillips, a media analyst in New York, pointing out that the issue may be banned by mass merchants like Wal-Mart and 7-Eleven. "When you rely on third party distributors, you are always running a risk," Mr. Phillips said.

Still, he said, that risk is minimal for W, which is owned by Advance Publications, the parent company of Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue. "Condé Nast has almost as much clout with distributors as any publisher in the world," he said.

But in an increasingly conservative social and political climate, some eyebrows are likely to be raised. "Americans are suddenly priggish," said Harold Koda, the chief costume curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which this year mounted an exhibition called "Bravehearts: Men in Skirts." "We seem to have retreated to a 1950's standard of morality."

In such a context, he said, "W's photographs can be a really potent social critique."

gogopilgrim

Member

- Joined

- Nov 27, 2003

- Messages

- 529

- Reaction score

- 1

oh my god, it's oxford st on a saturday night!

Originally posted by o2w@Sep 11 2004, 08:52 PM

oh my god, it's oxford st on a saturday night!

[snapback]364018[/snapback]

Originally posted by o2w@Sep 11 2004, 09:52 PM

oh my god, it's oxford st on a saturday night!

[snapback]364018[/snapback]

HAHAHA!

hollyslookingdry

Member

- Joined

- Jan 5, 2004

- Messages

- 935

- Reaction score

- 0

I thought the first guy was a girl until I saw his chest...

breathe0xygen

I loved you

- Joined

- Aug 24, 2004

- Messages

- 5,055

- Reaction score

- 5

Originally posted by hollyslookingdry@Sep 12 2004, 02:46 PM

I thought the first guy was a girl until I saw his chest...

[snapback]364229[/snapback]

me too, i froze for a moment to think.

me too, i froze for a moment to think.i thought the first guy was a girl until I saw the second pictureOriginally posted by hollyslookingdry@Sep 12 2004, 08:46 AM

I thought the first guy was a girl until I saw his chest...

[snapback]364229[/snapback]

Originally posted by o2w@Sep 12 2004, 01:52 AM

oh my god, it's oxford st on a saturday night!

[snapback]364018[/snapback]

more like shaftesbury avenue

more like shaftesbury avenue

that is really disturbing actually

yesturday just off charing cross road i saw a REALLY GOOD LOOKING GUY.....i mean REALLY good looking.......but

he was wearing white hotpants and knee high black boots with a 5' stiletto and he was running after a taxi screaming in that ****** kinda voice 'no you didaaaanttttttttt'

he was wearing white hotpants and knee high black boots with a 5' stiletto and he was running after a taxi screaming in that ****** kinda voice 'no you didaaaanttttttttt' its such a shame he was so good looking

its such a shame he was so good lookinggogopilgrim

Member

- Joined

- Nov 27, 2003

- Messages

- 529

- Reaction score

- 1

Originally posted by Acid@Sep 13 2004, 05:57 AM

more like shaftesbury avenue

that is really disturbing actually

yesturday just off charing cross road i saw a REALLY GOOD LOOKING GUY.....i mean REALLY good looking.......buthe was wearing white hotpants and knee high black boots with a 5' stiletto and he was running after a taxi screaming in that ****** kinda voice 'no you didaaaanttttttttt'

its such a shame he was so good looking

[snapback]364968[/snapback]

I meant Oxford St in Darlinghurst (Sydney)

funny, on the bus on Saturday night was a guy in hotpants, a halter top and stack heels telling everyone on board his life story - how he was a rent boy, what he had been doing that night, etc etc etc. He was cute in a drug ravaged kinda way.

Meisel should come to Sydney! Karl and Hedi did. If he came for the Sleaze Ball there would be plenty to photograph.

TheSoCalledPrep

Active Member

- Joined

- Nov 30, 2003

- Messages

- 5,282

- Reaction score

- 1

I like it..... so unexpected. It will drive the teenybopper and uppercrust wannabe readers up the wall

Similar Threads

- Sticky

- Replies

- 2K

- Views

- 768K

- Replies

- 4

- Views

- 4K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)