-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

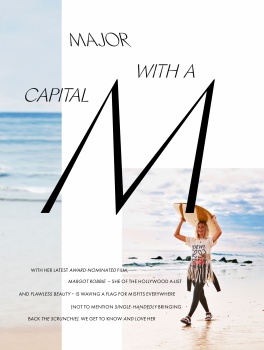

Margot Robbie

- Thread starter melfreya

- Start date

SallyAlbright

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2013

- Messages

- 2,524

- Reaction score

- 129

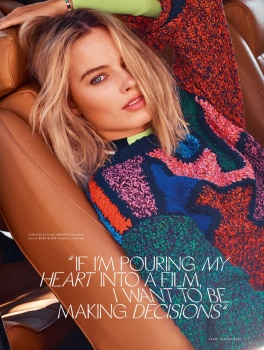

She looks great in Chanel!

MirandaPriestly

Member

- Joined

- Nov 17, 2010

- Messages

- 407

- Reaction score

- 0

I love both looks on this page.

SallyAlbright

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2013

- Messages

- 2,524

- Reaction score

- 129

Cool feature on Margot in the Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/feb/03/margot-robbie-woman-lead-flop

Nostalgic, nodding to herself, Margot Robbie walks around the deserted London bar a little in the manner of a soldier returning to the site of a heavy battle. A few years ago, when the Australian actor’s film career was getting going, when she was a Neighbours graduate who had been cast in a Martin Scorsese film, The Wolf Of Wall Street, Robbie lived nearby. The 27-year-old was one of a cluster of friends who squeezed into a rented home in Clapham meant for half that number, to save money. In the evenings, to stretch their limbs and get drunk, the gang would roll out to this bar.

“The best times,” says Robbie, remembering meandering conversations, in-jokes, budding love affairs and business decisions, big hangovers. The bar looks different at 10 in the morning, day-lit, set up for brunch. But, she remembers, there used to be a good sofa upstairs, past the table-football table, near the fireplace... “Here,” she says, pleased, settling in.

Robbie left London about a year ago, around the time she married her husband, Tom Ackerley, and moved to Los Angeles. She has flown back in to attend a screening of her new film, I, Tonya, ahead of its UK release. In a few hours she’ll be at a posh cinema, sitting in the dark and evaluating the audience’s every response. Robbie stars in this dark, low-budget comedy-biopic about the wayward American figure skater, Tonya Harding – and also produced it. This means having more skin in the game. It means “daily emails, saying what percentage we’re up or down in what cities, what demographics are responding in what way, what the reviews are saying”. Robbie collapses back on the sofa. “Super nerve-racking. Super exciting. I hadn’t been involved in this part before.”

She shucks off layers: an overcoat belonging to a girlfriend, a scarf she pinched from around the throat of her husband. About 36 hours ago, Robbie was on the east coast of Australia, visiting her mum; her piecemeal outfit was assembled early this morning after the actor opened her suitcase and realised she’d flown to wintry Europe without remembering to pack any warm clothes. Tanned, with Oz-sunned hair, she is by some distance the healthiest-looking person in the bar. Waiters ferrying brunch plates put some extra dash in their stride; the guy bringing her a cup tea gets flustered arranging the sugars; the one dog in the place seeks her out. Only a slightly dazed, finger-clicky energy gives away the fact that Robbie is trying to outrun some pretty serious jet lag, pinging everywhere and anywhere around the world, trying to give her movie its best chance of success.

“Don’t jinx me!” she says, when it’s pointed out that early indicators have been promising. But they have. At the Oscars in March, Robbie will be up for the best actress award against the big guns: Meryl Streep; Frances McDormand. Judges for the Golden Globes liked I, Tonya enough to give it three big-category nominations, and one win: for Allison Janney, in a supporting role as Harding’s mother LaVona. With the director, Craig Gillespie, and screenwriter, Steven Rogers, Robbie has managed the very delicate trick of presenting a subject who is both ridiculous and utterly sympathetic; a victim we’re not encouraged to patronise and a culprit we don’t much feel like condemning. Harding herself, now living in happy obscurity, gave the finished film her blessing.

I, Tonya is especially successful when dealing with the central contradiction of Harding’s life. She is infamous for a single, shocking act of violence – an attack, in January 1994, on a rival American figure-skater, Nancy Kerrigan, that was orchestrated by Harding’s ex-husband, Jeff Gillooly. Gillooly’s notion had been to hospitalise Kerrigan and so further Harding’s sporting chances. The crime, quickly exposed, made news worldwide; it made Harding notorious, reviled, an easy joke. What was never so well understood was the violence that underpinned her own life. Harding was beaten by an abusive mother and beaten by Gillooly when they were married. The new biopic crystalises this essential irony with a daring, show-stealing joke that’s delivered direct to camera by Robbie. “Nancy gets hit once,” she drawls, summoning Harding’s wry humour, “and the whole world sh*ts.”

Rogers’ script for I, Tonya had been doing the industry rounds for a while when Robbie and some colleagues secured the rights. Domestic violence featured heavily from its earliest writing, the portrayal of it sometimes on the border between seriousness and silliness. Was Robbie ever uneasy about this particular strand of humour? “Oh, from the get-go, from the second I read the script,” Robbie says. “I worried about the handling of the domestic violence and how we would achieve a specific tone.”

Though she did not meet Harding herself until a few weeks before the shoot, Robbie’s instinct was that to leave out the violence in her home life would have felt like a kind of censorship, “a disservice to Tonya and to anyone who suffered from domestic violence”. At the same time, they were supposed to be making a comedy. Gillespie “came up with the idea of breaking the fourth wall in those moments – to look at the camera. And that made sense to me, because Tonya’s emotionally disconnecting from what happens to her in those moments. You can see the character has accepted it [the violence], as just ‘the way life is’, as she put it. It was a repetitive cycle, so regular for her she could speak about it matter-of-factly.”

To be a part of dicey decisions about tone, to have a greater stake in artistic risk: this was why Robbie wanted to produce. “Not just,” she says, “to be the face of the film with – oh well! – no say in how it was written. Or rewritten. Or directed. Or budgeted. Or marketed. Or who it was sold to. Or how.”

It’s not a coincidence that this is the first time in a five- or six-year movie career Robbie has played the lead. She’s been in superhero flicks (2016’s Suicide Squad) and Oscar worthies (a cameo as herself in 2015’s The Big Short); there are some fascinating supporting roles coming up, not least as Elizabeth I in Josie Rourke’s Mary Queen Of Scots.

But this is the first time she’s been able to ring home and say: “Mum, I’m the main part.” Previously, Robbie says bluntly, she’d been bet-hedging. “It’s a big step, playing a lead, a step I’ve been hesitant to make. All the weight of the film rests on your shoulders. And if it doesn’t work? It’s that much harder for you to get a lead role again – especially if you’re a woman.”

Robbie leans forward and bunches her fingers, a characteristic gesture. “I feel like guys get a few more chances to be the lead in a flop. If you’re a woman, and it flops? Good luck getting another one.”

The third of four siblings, Robbie grew up on Australia’s Gold Coast, a train-hop south of Brisbane, in Queensland. Her mother is a physiotherapist, her father worked in farming; they separated early in Robbie’s life, an event that shaped a large part of her adult character, she says, though she’s loth to talk about it in detail. Robbie was sporty, competitive, took part in school plays, got especially good grades in legal studies. When she graduated she was 17, “and everyone said I should go to university, study law”.

But she’d noticed, growing up, that whenever her mother spoke of her own youth she zeroed in on the exciting stuff – the adventure, the backpacking, never the study. “I decided I didn’t want to spend money I didn’t have, on a subject I didn’t want to do, only to be paying back debt for the rest of my life. Why abide by that invisible rule?”

She went south to Melbourne instead, and took a day job in a Subway fast-food restaurant. Her medium-term plans were to get work acting, or to travel, and in the end she managed both, fitting in a backpacking tour of Europe in the middle of a two-year, 327-episode run as a regular on Neighbours. When her soap contract came to an end she was offered a renewal, but instead chose to get on a plane again, this time to America. She was cast in a new TV series, about 1960s cabin crews, called Pan Am.

Some actors start out at a Rada or a Juilliard, others set themselves to follow the example of a Brando or a Day-Lewis, but Robbie had trained at the Ramsay Street school and it was there that she learned a professional technique that has always served her well: let’s call it the no-trailer method. “On Neighbours there were no trailers,” she says, “you just, like, sat with everyone.” Karl and Susan, the sparkies, the assistant directors, they all sloshed around together in a big room during lulls. “You shared the kitchen. You hung out.”

When Robbie got her gig in Pan Am, which was broadcast for a few months before its cancellation in 2012, she found it “lonely. You were supposed to be all segregated into different departments, which felt weird. I remember knocking on other people’s doors and saying: ‘Uh, do you want to hang out?’ ” She liked the informal nooks where the runners and makeup deputies and third-rung assistant directors (the third ADs) killed time. “I don’t know, I was closer in age to them. They seemed more like my friends from back home.”

Soon after the show’s cancellation, Robbie, gutted but unchastened, angry-auditioned herself into some big movies. “I would go in thinking: ‘You ****ing wait, look up from your papers, watch me, I’m going to blow your ****ing mind.’”

Scorsese cast her in The Wolf Of Wall Street, as Leonardo DiCaprio’s wife, the director especially impressed that she’d had the guts to thump an unprepared DiCaprio, mid-reading. She was in a Richard Curtis movie, About Time, and then supplemented a star-rich cast adaptation of Suite Française, shot on location in Belgium. The sets had scaled up, so had Robbie’s pay cheques, but she kept finding herself gravitating to the circles of folding chairs where the runners and teamsters gathered. On Suite Française, the troupe of third ADs were drawn mostly from London. “We became really close. You spend so much time with your crew – I mean, if you want to.”

The Australian accent had stuck with her from home, as had her Australian appreciation for a good nickname. The new gang did not disappoint on this score. “I got called Maggie, Margz, Mags, Maggles…” Suite Française was ultimately a forgettable film, but the drunken nights out were memorable, and a tight friendship group formed. Promises were made to stay in touch, and a little while later, in January 2014, when Robbie was coming through London for the premiere of Wolf Of Wall Street, the gang regathered. Paramount had put her up in a ritzy hotel room. Everyone packed in.

“We were like: ‘Wouldn’t it be funny if we all lived together?’ Someone said: ‘But you don’t live in London,’ and I said: ‘I don’t live anywhere. I’ll move.’ Three days later we signed a lease in Clapham. I didn’t even see the place – I had to fly out to the Golden Globes [where Wolf Of Wall Street had been twice nominated] three hours after we made the decision.”

“Obviously ADs get paid like ****. So we had to, ah,” Robbie chuckles, “fit quite a few people in to a small place.” Five ADs, a rising movie star, an old friend from Australia, Sophia Kerr, now working as Robbie’s assistant. That made seven, all crammed into a three-bedroom home. Robbie had booked a job in London for a year, a CGI-heavy remake of The Legend Of Tarzan that was eventually released in 2016. At around the same time one of the housemates, Tom Ackerley, was third-ADing on a Mission: Impossible sequel.

At the start of their relationship, Robbie recalls: “We kept it a secret. Because we weren’t really taking it seriously. ‘Oh, whatever, we’re just mates, we’re just mates.’ And then… everyone found out.”

Was that awkward, two of the seven coupling up?

Robbie draws out a long: “Ummm”. She’s thinking about how much she wants to commit to the record here. “It was dramatic. I’m not going into the details, but **** hit the fan. Our house turned into The Jerry Springer Show for a moment there. But then the dust settled, and it was all good.”

The wider friendship survived? “Everyone was, like: ‘No! This is going to ruin our group!’ And then it didn’t. It was fine.”

SallyAlbright

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2013

- Messages

- 2,524

- Reaction score

- 129

Continued

Robbie and Ackerley married in December 2016, on the beach in Australia, around the time she started her intensive ice-skating training for I, Tonya. A great picture of the event was put up on Instagram, the antithesis of an OK! wedding shot: the newlyweds enjoying a snog on the sand while the bride thrust out her ring finger at the camera. The suggestion of profanity (**** you, we’re married!) fit Robbie’s character pretty well. In conversation, she swears as frequently as an irate sports fan. “It’s from working on film sets, my God. I try and control it. My mum gets so upset.” She favours life on the boisterous side, something she puts down to growing up in “a loud house, very loud. It’s one reason I’ve always lived with roommates – quietness is deafening to me, I hate it so much.”

In fact, she says, when she and Ackerley were first married, “it was our roommates who told us: ‘You guys had a wedding. You have to live on your own now.’ It honestly hadn’t occurred to us. We were, like: ‘Hm? What? Just the two of us? That’s gonna be weird.’ And the first time we were in a house, the two of us, it was weird. Nice. But we missed having heaps of people around.”

Ackerley is a co-founder of Robbie’s production company. So is Kerr, the childhood friend, and another member of the old Clapham crowd, Josey McNamara. All are co-producers on I, Tonya. They named their company LuckyChap, which I’d guessed must have some sly secret meaning. “Ha!” says Robbie. “No, we were just drunk. We were here when we came up with it. And nobody can remember why. I think we were talking about Charlie Chaplin…”

Until they founded LuckyChap, Robbie’s Hollywood career had only rarely required that she actually be in Hollywood. “And I’ve still never made a movie there.” As fledgling producers, though, Robbie and her co-founders at LuckyChap decided they needed to be closer to the inner cogs of the machine. They moved en masse to Los Angeles in November 2016, just before the presidential election. That must have seemed...

“Interesting?” Robbie cuts in. “Five days before Trump became president? Yeah. It was an interesting time to move to America.”

In her particular industry, we now know, the larger convulsions were still to happen. The Harvey Weinstein scandal blew up in autumn 2017, and in those first weeks many prominent actors have spoken out in protest at the primitive sexual politics of Hollywood. Some told personal stories about mistreatment, others offered a more general take.

“Every conversation is a productive conversation,” says Robbie, who favours the general take. “Because once that conversation’s happened it can alter the next one.”

Did there come a moment where she saw what was happening, and had to ask herself: will I contribute? “It’s tricky,” she says. “It’s that thing where, like… Who am I to speak on this topic? Who wants to hear from me?”

How she dealt with this sense of trickiness was interesting. In October, immediately post-Weinstein, Robbie was asked to speak at an event in celebration of women in film. These were the stormy beginnings of the #MeToo movement, and the tendency at the time had been a top-heavy focus on celebrity – on the perpetrators and victims of sexual harassment whose names and faces we knew. Before she sat down to write her speech about “women in film”, Robbie turned to those other women in film who until then had been overlooked: the runners and deputies and assistants, the lower-rung employees with whom she’d sat in circles on folding chairs for hours on set; with whom she’d lived.

“I went on our girl group [on WhatsApp], my London girls, who are all crew members.” She asked them: what have you been through? What do you feel like saying that hasn’t been heard? “My phone went ****ing nuts. They were angry. I was surprised by how angry they were. I was overwhelmed by how much they felt they’d been bottling up.” Together on their phones these women wrote Robbie’s speech, and when she delivered it at the event, she did so in the first-person plural of the chat group.

“Being a woman in Hollywood means you will probably have to fight through degrading situations,” Robbie said that night. “Struggle for the right to earn a living, the right to be heard, even the right to be safe from harm… [Be] in the shadows of big trees, constantly reminded that we only grow in the sunshine they allow us... When you take away Hollywood,” the speech concluded, “we are all just women. All facing the inequalities that being a woman brings with it.”

On the sofa in the bar, Robbie shrugs. The speech came and went, subsumed by the onslaught of sensational news. But she’s proud of it. “I didn’t feel fake, saying it, because I knew I was speaking on their behalf. That felt more important than my sole opinion.” She can see there’s a hunger for individuals like her, prominent actors in the thick of things, to offer opinions about the past and present – and to say that everything’s likely to get better after the upheavals of 2017. “But, look, who am I to say? I’ve got no idea. All I can speak to is what it looks like from my point of view.”

From her point of view, so far, it’s been a case of smaller, incremental epiphanies. Robbie gives an example. There was a conference call she was on, recently, to discuss a film she had in development. Robbie and a friend, a screenwriter, “were the only two women on the phone call. And we’d really had to stand our ground, to fight for something specific on this project. Afterwards we messaged each other, to ask: ‘Hey, was I a bit too pushy there? Did I sound like a b*tch just then?’ We sent each other pretty much the exact same message, at the exact same time.”

Robbie widens her eyes. “Fuuuuuuuuuuuuuck. Because – do you think any of the men on that phone call texted each other, after, to ask if they sounded like a b*tch? For putting an opinion forward? No. None of them would have thought twice about any of the things they said. You have those epiphany moments and this was one. And that’s not just our industry. That’s every industry.”

She climbs inside her borrowed coat again; wraps on the scarf. A car is waiting, to nip Robbie to the I, Tonya screening. Our conversation has reminded her of a bit in the film, when Harding is moved to comment on the outdatedness of competitive women’s figure-skating, its tutus, its sequins, “this old-timey vision of what a woman’s supposed to be”. The skater’s response is to glide over to the judges’ table at a competition – to face the arbitrators of this dated industry directly, and to stick up a middle finger at them.

Just an awesome moment, Robbie says. “And, sadly, pretty relevant – right?”

Yohji

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 12, 2015

- Messages

- 11,344

- Reaction score

- 3,433

I was reading an article from The Times with Saoirse Ronan's stylist Elizabeth Saltzman and she mentions an Oscar contender possibly being the new face of Chanel. Do you think it could be Margot? She's worn Chanel twice this season and seems like the most feasible option.

What about last year’s Oscars brouhaha in which Karl Lagerfeld wrongly made an initial claim, later retracted as false, that Meryl Streep had pulled out of wearing a Chanel dress when another brand offered to pay? “I didn’t believe it at the time. I thought someone hadn’t done their homework. Chanel has contracts with people.” She pauses. “I am pretty sure we are going to be hearing about someone on the carpet this year who will be the new face of Chanel.” She mouths the name of another Oscar contender.

Actress Margot Robbie at the Outstanding Performers Honoring Margot Robbie and Allison Janney Presented By Belvedere Vodka during The 33rd Santa Barbara International Film Festival at Arlington Theatre on February 8, 2018 in Santa Barbara, California.

zimbio.com

zimbio.com

SallyAlbright

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2013

- Messages

- 2,524

- Reaction score

- 129

That would be cool, Margot would be a beautiful Chanel face, and it would keep her from being stuck with LV.

catherine88

Active Member

- Joined

- Jun 11, 2011

- Messages

- 9,960

- Reaction score

- 10

Margot for Chanel or Prada.. That would be something!

SallyAlbright

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2013

- Messages

- 2,524

- Reaction score

- 129

Also, she looks stunning in the Prada outfit above. I say it so often that it's boring, but she always looks beautiful.

HeatherAnne

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2008

- Messages

- 24,230

- Reaction score

- 994

Margot as a Chanel replacement for Diane Kruger who seems to be on Karl's outs? I could see it.

Enjoyed the article, she seems to have a bit of a tomboy personality that I dig.

Enjoyed the article, she seems to have a bit of a tomboy personality that I dig.

Rose n Toast

Active Member

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2013

- Messages

- 2,342

- Reaction score

- 0

Love the Pfieffer vibes

SallyAlbright

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 6, 2013

- Messages

- 2,524

- Reaction score

- 129

Is that her in the last shot? Much longer hair, and the face doesn't look like her. Either way, beautiful shoot.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 502

- Views

- 92K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)