Lola701

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 27, 2014

- Messages

- 14,518

- Reaction score

- 39,919

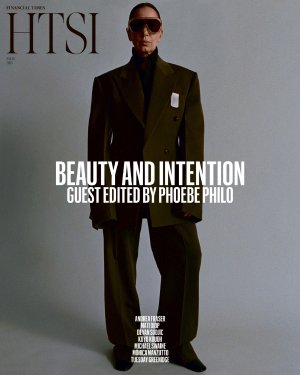

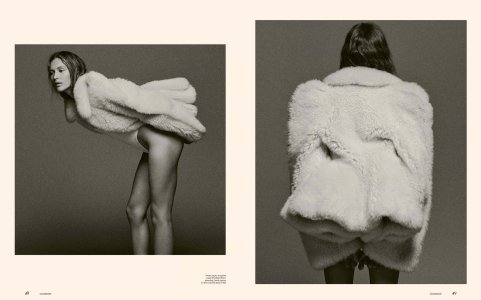

Oh interesting.It's Phoebe's.

I bet it looks better flipped to the back, over a column dress or a very demure jumpsuit.

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

Oh interesting.It's Phoebe's.

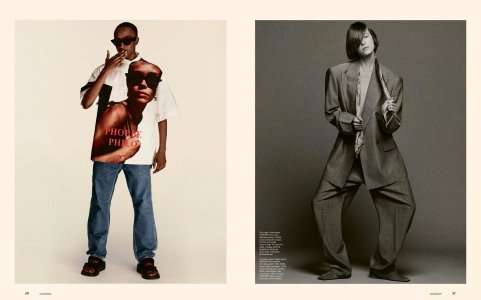

That was so badphoebe philo's best designs were for chloe and it's been downhill ever since.

Thought it was boring to death.I felt nothing at all. It was just reheating nachos, very dry.

Jane how did her 70s schtick which I enjoy time to time and that’s it I guess.

To who?Phoebe Philo should shut down her boring label and come back in 5 years, IF she’ll have something to add to the conversation and fashion design. Until then, she’s just making her designs less and less desirable. 🤷🏼♀️

this is an interesting opinion!Phoebe Philo should shut down her boring label and come back in 5 years, IF she’ll have something to add to the conversation and fashion design. Until then, she’s just making her designs less and less desirable. 🤷🏼♀️

Are the fans present in the room tonight?I don’t understand the hate toward current Phoebe Philo. I’m far from being a fan of her, but if people rarely complain about the pricing of The Row, then why isn’t Phoebe shown the same level of tolerance? Do you expect her brand to be as successful as Tom Ford label or sth? Her brand is 100% fan service and very niche in a way, no one’s forcing you to like it.