Viva Viv: Vivienne Westwood talks art, sex and being a grandmother

story from the telegraph UK

A slightly scary prospect, meeting Vivienne Westwood. Downstairs, in the lower levels of her Battersea studio, a swarm of workers buzz around the hive, cutting fabric, changing thread, saying things to each other in hushed voices like, 'Have you got the mesh and the fusing?' When the queen finally arrives it is on her bike - an alarming figure with orange hair, tweed trousers and a red tartan bomber jacket.

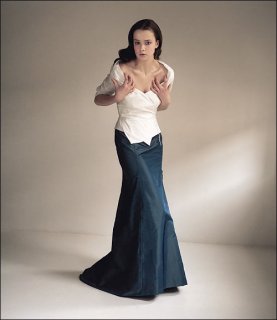

She changes into a gold and petrol-blue dress, part toga, part ball-gown, with 9in-high lace-up boots, and has her photograph taken there among the bolts of cloth and the women in jeans. It's the shock of tiara'd hair, or the arch of her drawn-on red eyebrow, or her habit of walking like a model - one arm still, one arm swinging - but she looks like Tilda Swinton as the Ice Queen. Or Elizabeth I. 'Who's got music on?' she asks, beadily imperious. 'It's not allowed.'

Upstairs, in her office, she studies herself in a mirror before unwrapping the dress and unlacing the boots. Underneath she is wearing knee-length grey socks, her husband's boxer shorts and a shell-pink bra from Agent Provocateur - the lingerie shop co-founded by her younger son. Her skin is pale, with a map of blue veins. She has brought a third set of clothes to wear - a green gingham shirt that falls in folds, and her favourite drop-crotch, boiled-wool trousers. 'I love these trousers. I often wear samples, but that pair shrank too small so I sent them to my granddaughter.' Her voice is soft Derbyshire. She sits at her desk, on a high stool, and wriggles her feet into slippers. 'Oh. I've forgotten my glasses.' She gets up. 'I can't think without my glasses.'

Westwood, it is often said, is a woman of contradictions. At 66 she's the grande dame of fashion, a grandmother who wore an 'urban guerrilla's cap' to the Palace to be made a dame in 2006. (For her OBE she was photographed without her knickers, though she claimed just to have forgotten to put them on.) She rails against consumerism, while designing diamond-studded punk collars, and protest, even anti-fashion, T-shirts (I AM EXPENSIV) costing £90 a pop. 'Buy less,' she exhorts, yet her diffusion Anglomania line and new ready-to-wear Red Label - the highlight of this year's London Fashion Week - might well encourage you to buy more.

She dressed the Sex Pistols and Adam Ant, arranged chicken bones to spell out f-, invented the anarchy sign, and yet there are few designers as concerned to tease and to clinch, to puff and to flatter, the curves of the female form. In conversation she quotes Aldous Huxley and Bertrand Russell, but it is Saint Laurent for whom she becomes literally breathless: 'Nobody could do what he did. It was the perfect touch; very, very French, very rococo. You're building a pack of cards - it's almost like bad taste - you put the final thing on the top and it just… it's like going on a tightrope over Niagara, you achieve this incredible triumph.'

This is to come, though. At the outset, glasses on, top of her desk swept clean with the tips of her fingers, Westwood wants to talk about her manifesto - Active Resistance to Propaganda, a semi-dramatic rallying-cry through the interaction of such characters as Alice in Wonderland and Pinocchio, for Art and Thought and Culture (available at www.activeresistance.co.uk). She used to be a teacher. 'I'll come back to that point later,' she says, looking down on me (I'm on a much lower stool) and, 'moving now from the subject of my kids to Karl Marx'. But you feel it's not a classroom she is trying to keep in check so much as her own ideas. She has thoughts on everything. On politics: 'It's a scandal that Tony Blair is in a position to negotiate the Middle East. It's like asking the wolf into your house. I have considered voting Conservative because I am so against the Labour party.' On art: 'It needs to be representative.' Classics: 'The crucible of our whole civilisation.' If the manifesto has laid her open to ridicule it is because of its structure and its grand hopes - 'to help change public opinion and get a better sort of world' - but all Westwood wants is that we read more books and think for ourselves. She has a refreshing attitude to learning. 'Every time I have to look up a word in the dictionary,' she says simply, 'I'm delighted.'

Westwood's life has itself spanned several English cultures. She was born Vivienne Swire in Tintwistle, a village on the borders of Derbyshire and Cheshire, where her father worked in the Wall's sausage factory and her mother in a greengrocer's. They moved south to Harrow to run a post office, and Vivienne went to art school before becoming a primary-school teacher in north London. 'My sympathies were with the kids. I could understand why they were naughty - the classes were so oversized. You couldn't get round to coping with them.' She was married to her first husband, Derek Westwood, a factory apprentice, and had one son, Ben, when she met her second, Malcolm McLaren, the future Sex Pistols manager. Together they opened a shop on the King's Road, called Sex in one of its incarnations, which gave a visual expression to punk. Even then, she says, she stood aside. 'I was always thinking, "Why don't people tear their own clothes if that's what they want? Why buy a torn T-shirt from me?"' What does she think of punk now? 'If you hear Anarchy in the UK today your hair stands on end. It gives you the shivers. But some of them are still stuck on their pedestals. I moved on. I realised that it's only ideas that are subversive in the end. It's not rushing around being a rebel.'

She had a second son, Joe, while she was with McLaren. Was she a good mother? 'I never tried to impose things. And I felt my sons should respect me. It would have to be a real emergency, for example, if they would wake me in the middle of the night, or even early in the morning. But I always thought what I could give to my children were my opinions. I don't think I was very good at educating my children…' She breaks off and dips a finger in the froth of her cappuccino. 'Oh, maybe I was in a way.' She sent them both to boarding school in the end. 'My eldest son [a p*rn photographer] reads and my younger son… well, until a year ago he had only read The Great Train Robbery and a history of Jimmy somebody or other, that hard-tough case in Scotland. But then he's Malcolm's son as well, so…'

She doesn't see McLaren at all any more. 'I was thinking, I do all these shows in Paris [where he lives] but I don't think of inviting him even. I think he's been too bad to me. Finally I decided he wasn't worth seeing. Sorry, I shouldn't say it in that way, but I don't expect he'll mind.'

Since 1992, Westwood has been married to Andreas Kronthaler, who is 25 years younger than her. They met when she was teaching design in Vienna - he was her student, 'the most talented person in fashion I'd ever met', and she hired him on the spot. She says they are perfectly matched. 'He needs my calmness and my grounding because he's very hysterical. He gets overwhelmed by himself. Also, I think men really do like to put women on a pedestal. Andreas is like that. He's a big man. He likes pulling cloth out. On the other hand, I'm very concrete and he's wonderful at developing things - he's sorted out our production - and turning them into something else.' She pauses to think. 'Sometimes it does happen that I arrive in Paris and the eveningwear - I don't even recognise it. I have to have it explained to me: "Don't you know, you stupid woman, it's the thing you started to do and now it's become this other thing." And sometimes I don't know where it starts and ends.' She breaks off. There's a slight edge of confusion in her voice.

It's an unconventional relationship in many ways - Kronthaler is bisexual and Westwood has often said sex is overrated. 'I've never been interested - I've never worried - what he's up to or anything. I let him go - not let him, I mean he goes - on holiday by himself. And he'll change his clothes two or three times a day, even on the beach. And that man - he has to change his underwear. He has to feel things. He's a very sensual person.'

When he is away she reads and gets on with what she calls All These Other Things. She always has a project on the go. She is trying to get her manifesto turned into a play and has just collaborated on a book of photographs, featuring among others Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell and Jerry Hall. Westwood is rarely gushing, but when she talks about these women it's as if she can't find enough adjectives. 'Those supermodels, they are the greatest thing. Each one of them seems to be the epitome of an idea or a look, or a feeling. She looks beautiful does Kate. Stunning. And Jasmine Guinness? Oh, she's gorgeous. What a beauty. What an amazing voluptuous woman.'

The book also features Westwood's sons and ten-year-old granddaughter, Cora, whom she adores. 'I mean, when she was eight she was reading these really, really long books, 300 pages and stuff.' She sighs. 'If somebody's a reader, they can do anything.' Does Cora like clothes? Westwood makes a face like a disappointed tortoise. 'She's really conservative. I'm very disappointed in that. She wears jeans. I think jeans are terrible. Those boiled-wool trousers I was talking about that shrank, the ones I sent to her? Well, I took Cora to the terracotta soldiers [sic] and after a bit I said, "I was really hoping that you would wear those trousers." She said to me, "It's more important if people are nice people than what they wear."' Westwood's expression is ambiguous. It's almost as if she is impressed by her granddaughter's gumption. So what was her answer? 'I said, "Rubbish."'

The other day Westwood was cycling through Clapham, where she lives, on her way to give a reading of her manifesto. 'I had on my cape. I can get bored of all my wonderful cutting principles and my cape is just a single piece of cloth threaded through. And I had this skirt that just loops up as well. I was trying to race along with my cape flying and these little kids - well, teenagers - called out after me, "Speed it up, Grandma." I thought, that's great. If there was another old person on a bike they probably wouldn't have noticed them.' She juts her chin out, quite regal again. 'I made them wake up for a minute.'

story from the telegraph UK

A slightly scary prospect, meeting Vivienne Westwood. Downstairs, in the lower levels of her Battersea studio, a swarm of workers buzz around the hive, cutting fabric, changing thread, saying things to each other in hushed voices like, 'Have you got the mesh and the fusing?' When the queen finally arrives it is on her bike - an alarming figure with orange hair, tweed trousers and a red tartan bomber jacket.

She changes into a gold and petrol-blue dress, part toga, part ball-gown, with 9in-high lace-up boots, and has her photograph taken there among the bolts of cloth and the women in jeans. It's the shock of tiara'd hair, or the arch of her drawn-on red eyebrow, or her habit of walking like a model - one arm still, one arm swinging - but she looks like Tilda Swinton as the Ice Queen. Or Elizabeth I. 'Who's got music on?' she asks, beadily imperious. 'It's not allowed.'

Upstairs, in her office, she studies herself in a mirror before unwrapping the dress and unlacing the boots. Underneath she is wearing knee-length grey socks, her husband's boxer shorts and a shell-pink bra from Agent Provocateur - the lingerie shop co-founded by her younger son. Her skin is pale, with a map of blue veins. She has brought a third set of clothes to wear - a green gingham shirt that falls in folds, and her favourite drop-crotch, boiled-wool trousers. 'I love these trousers. I often wear samples, but that pair shrank too small so I sent them to my granddaughter.' Her voice is soft Derbyshire. She sits at her desk, on a high stool, and wriggles her feet into slippers. 'Oh. I've forgotten my glasses.' She gets up. 'I can't think without my glasses.'

Westwood, it is often said, is a woman of contradictions. At 66 she's the grande dame of fashion, a grandmother who wore an 'urban guerrilla's cap' to the Palace to be made a dame in 2006. (For her OBE she was photographed without her knickers, though she claimed just to have forgotten to put them on.) She rails against consumerism, while designing diamond-studded punk collars, and protest, even anti-fashion, T-shirts (I AM EXPENSIV) costing £90 a pop. 'Buy less,' she exhorts, yet her diffusion Anglomania line and new ready-to-wear Red Label - the highlight of this year's London Fashion Week - might well encourage you to buy more.

She dressed the Sex Pistols and Adam Ant, arranged chicken bones to spell out f-, invented the anarchy sign, and yet there are few designers as concerned to tease and to clinch, to puff and to flatter, the curves of the female form. In conversation she quotes Aldous Huxley and Bertrand Russell, but it is Saint Laurent for whom she becomes literally breathless: 'Nobody could do what he did. It was the perfect touch; very, very French, very rococo. You're building a pack of cards - it's almost like bad taste - you put the final thing on the top and it just… it's like going on a tightrope over Niagara, you achieve this incredible triumph.'

This is to come, though. At the outset, glasses on, top of her desk swept clean with the tips of her fingers, Westwood wants to talk about her manifesto - Active Resistance to Propaganda, a semi-dramatic rallying-cry through the interaction of such characters as Alice in Wonderland and Pinocchio, for Art and Thought and Culture (available at www.activeresistance.co.uk). She used to be a teacher. 'I'll come back to that point later,' she says, looking down on me (I'm on a much lower stool) and, 'moving now from the subject of my kids to Karl Marx'. But you feel it's not a classroom she is trying to keep in check so much as her own ideas. She has thoughts on everything. On politics: 'It's a scandal that Tony Blair is in a position to negotiate the Middle East. It's like asking the wolf into your house. I have considered voting Conservative because I am so against the Labour party.' On art: 'It needs to be representative.' Classics: 'The crucible of our whole civilisation.' If the manifesto has laid her open to ridicule it is because of its structure and its grand hopes - 'to help change public opinion and get a better sort of world' - but all Westwood wants is that we read more books and think for ourselves. She has a refreshing attitude to learning. 'Every time I have to look up a word in the dictionary,' she says simply, 'I'm delighted.'

Westwood's life has itself spanned several English cultures. She was born Vivienne Swire in Tintwistle, a village on the borders of Derbyshire and Cheshire, where her father worked in the Wall's sausage factory and her mother in a greengrocer's. They moved south to Harrow to run a post office, and Vivienne went to art school before becoming a primary-school teacher in north London. 'My sympathies were with the kids. I could understand why they were naughty - the classes were so oversized. You couldn't get round to coping with them.' She was married to her first husband, Derek Westwood, a factory apprentice, and had one son, Ben, when she met her second, Malcolm McLaren, the future Sex Pistols manager. Together they opened a shop on the King's Road, called Sex in one of its incarnations, which gave a visual expression to punk. Even then, she says, she stood aside. 'I was always thinking, "Why don't people tear their own clothes if that's what they want? Why buy a torn T-shirt from me?"' What does she think of punk now? 'If you hear Anarchy in the UK today your hair stands on end. It gives you the shivers. But some of them are still stuck on their pedestals. I moved on. I realised that it's only ideas that are subversive in the end. It's not rushing around being a rebel.'

She had a second son, Joe, while she was with McLaren. Was she a good mother? 'I never tried to impose things. And I felt my sons should respect me. It would have to be a real emergency, for example, if they would wake me in the middle of the night, or even early in the morning. But I always thought what I could give to my children were my opinions. I don't think I was very good at educating my children…' She breaks off and dips a finger in the froth of her cappuccino. 'Oh, maybe I was in a way.' She sent them both to boarding school in the end. 'My eldest son [a p*rn photographer] reads and my younger son… well, until a year ago he had only read The Great Train Robbery and a history of Jimmy somebody or other, that hard-tough case in Scotland. But then he's Malcolm's son as well, so…'

She doesn't see McLaren at all any more. 'I was thinking, I do all these shows in Paris [where he lives] but I don't think of inviting him even. I think he's been too bad to me. Finally I decided he wasn't worth seeing. Sorry, I shouldn't say it in that way, but I don't expect he'll mind.'

Since 1992, Westwood has been married to Andreas Kronthaler, who is 25 years younger than her. They met when she was teaching design in Vienna - he was her student, 'the most talented person in fashion I'd ever met', and she hired him on the spot. She says they are perfectly matched. 'He needs my calmness and my grounding because he's very hysterical. He gets overwhelmed by himself. Also, I think men really do like to put women on a pedestal. Andreas is like that. He's a big man. He likes pulling cloth out. On the other hand, I'm very concrete and he's wonderful at developing things - he's sorted out our production - and turning them into something else.' She pauses to think. 'Sometimes it does happen that I arrive in Paris and the eveningwear - I don't even recognise it. I have to have it explained to me: "Don't you know, you stupid woman, it's the thing you started to do and now it's become this other thing." And sometimes I don't know where it starts and ends.' She breaks off. There's a slight edge of confusion in her voice.

It's an unconventional relationship in many ways - Kronthaler is bisexual and Westwood has often said sex is overrated. 'I've never been interested - I've never worried - what he's up to or anything. I let him go - not let him, I mean he goes - on holiday by himself. And he'll change his clothes two or three times a day, even on the beach. And that man - he has to change his underwear. He has to feel things. He's a very sensual person.'

When he is away she reads and gets on with what she calls All These Other Things. She always has a project on the go. She is trying to get her manifesto turned into a play and has just collaborated on a book of photographs, featuring among others Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell and Jerry Hall. Westwood is rarely gushing, but when she talks about these women it's as if she can't find enough adjectives. 'Those supermodels, they are the greatest thing. Each one of them seems to be the epitome of an idea or a look, or a feeling. She looks beautiful does Kate. Stunning. And Jasmine Guinness? Oh, she's gorgeous. What a beauty. What an amazing voluptuous woman.'

The book also features Westwood's sons and ten-year-old granddaughter, Cora, whom she adores. 'I mean, when she was eight she was reading these really, really long books, 300 pages and stuff.' She sighs. 'If somebody's a reader, they can do anything.' Does Cora like clothes? Westwood makes a face like a disappointed tortoise. 'She's really conservative. I'm very disappointed in that. She wears jeans. I think jeans are terrible. Those boiled-wool trousers I was talking about that shrank, the ones I sent to her? Well, I took Cora to the terracotta soldiers [sic] and after a bit I said, "I was really hoping that you would wear those trousers." She said to me, "It's more important if people are nice people than what they wear."' Westwood's expression is ambiguous. It's almost as if she is impressed by her granddaughter's gumption. So what was her answer? 'I said, "Rubbish."'

The other day Westwood was cycling through Clapham, where she lives, on her way to give a reading of her manifesto. 'I had on my cape. I can get bored of all my wonderful cutting principles and my cape is just a single piece of cloth threaded through. And I had this skirt that just loops up as well. I was trying to race along with my cape flying and these little kids - well, teenagers - called out after me, "Speed it up, Grandma." I thought, that's great. If there was another old person on a bike they probably wouldn't have noticed them.' She juts her chin out, quite regal again. 'I made them wake up for a minute.'

I love how she thinks reading can get one anywhere--so true.

I love how she thinks reading can get one anywhere--so true.