part 2

"I've thought a lot about power," she says. "And whatever power I have is what my marriage gives me, my husband's power—and that's the power of an elected status. I'm not the kind of woman who thinks that if you marry a violinist you can play the violin. When you're famous, people come to you, but power means people have to come to you. Power's a real profession."

It is said that she soothes the impetuous Sarkozy. "She should get an allowance for services rendered to the state for calming him down," says Denis Olivennes, the head of the newsweekly Le Nouvel Observateur and a friend of Carla's. A sharp-tongued Parisian explains, "Sarkozy was perceived as a man without much culture when Carla came on the scene. She drags him to desperately abstract plays that he sleeps through, but he's thrilled; she makes him watch DVDs of foreign films in the original language; she's made him into the kind of man intellectuals can be seen with. She ennobled him; she made him elegant."

In 2008, the president, whose jagged energy—part giant turbine, part bug zapper—has often alarmed people, revealed himself to be an effective troubleshooter on the international scene. He took his appointed turn as head of the European Union and swiftly found a resolution to the conflict between Russia and Georgia; he managed to bring together Israel and Arab countries to create a "Union for the Mediterranean"; and when the financial crash happened, he herded the European countries into agreement with the British prime minister, Gordon Brown's, financial measures. In January, along with Egypt's Hosni Mubarak, Sarkozy was trying to broker discussions between Israel and Hamas. "He restored his image last year and showed he was a true president, someone capable of protecting the country," adds Olivennes.

The year 2008 was also the year that Carla brought out her third album, Comme Si de Rien N'Était ("As if nothing had happened"), on which she sings, "Je suis une enfant malgré mes quarante ans, malgré mes trente amants" ("I am a child despite my 40 years, despite my 30 lovers"), and, causing an even greater frisson, "Tu es ma came"—"You're my drug," said to be about Sarkozy. She also became immensely popular, obviously in love with her husband, behaving faultlessly in her official capacities while remaining her own person. "How can she possibly be so nice with so many people all the time?" asks Karl Lagerfeld.

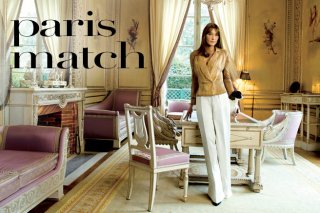

The woman with a past is a reader (Virginia Woolf's Mrs. Dalloway right now) and something of an introvert who says that when she sang in public, she felt protected because they were her own songs, her own music. There's a guitar slung across a chair, there are leather-bound collections—Verlaine, Hugo, Zola, Michelet—in the bookcase, and a turbaned Venetian Moor rises behind the Steinway. Lunch is served on trays on an upholstered ottoman, by a cook who has been with Carla's family since 1980. We're in haute boho land: Until her family fled Italy because of kidnapping threats from the Red Brigades in 1973, they lived in a castle outside Turin. Her mother, Marisa Borini, was a concert pianist who practiced seven hours a day; her father, Alberto Bruni-Tedeschi, was a wealthy businessman who wrote twelve-tone music and turned out not to be her father at all. Carla Bruni learned twelve years ago that her actual father was a classical guitarist named Maurizio Remmert, who now lives in Brazil. In a TV documentary about Carla that ran on New Year's Day in France, her mother said, "I am a person without guilt." The Bruni-Tedeschi household was rich, accomplished, intellectual, grand. It's the kind of background that allows someone to be generous, tolerant, and supremely casual. Her brother and sister went to university; Carla couldn't wait to leave home and earn her own living, as a model, at eighteen.

"One of the things I have in common with Nicolas is that we both love action, and jumping into modeling was a form of action." She modeled in New York for three years, sharing a loft in Tribeca with the actress Marine Delterme, until Véronique Rampazzo from the Marilyn agency encouraged her to move back to Paris in 1989. Véronique shaped Carla's career as one of the supermodels of the nineties and remains with her today as an unofficial press liaison. Carla worked alongside Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, Stephanie Seymour. Her friends were Karen Mulder and Farida Khelfa, the first and, to this day, only Arab model. I knew Carla then because I ran Paris Vogue. Her boyfriend was Arno Klarsfeld, a long-haired lawyer with a habit of Rollerblading to court. Sensible, sophisticated, with a perfect body and an inhumanly perfect ***, she was infinitely fluid on the runways—sexy at Versace, cool at Saint Laurent, playful at Galliano, classy in a multitude of uninspiring ensembles, classic in columns of crepe.

One day we were on the same plane. That month's Vogue had a cover line forbidding the shahtoosh, a shawl made of the chin hairs of Himalayan antelopes called chirus. A journalist had found out the Chinese were shooting the chirus. I was wearing an old shahtoosh. Carla came over to me and said, "You should be ashamed of yourself. You have to be coherent. If you forbid something, don't do it yourself." I took note that this woman was fearless and had an uncommon regard for cogency.

By 1998, when Bruni was 31, the bookings got rarer. She had always traveled with her guitar, but now, she says, "I had more time for music, so I worked four, five, six hours a day." She also started analysis—"Freudian. Four days a week on the couch. If you are lucky enough to have a privileged life, it's sad to remain infantile and spoiled. You have to get rid of your neuroses and take responsibility for your own life." She still sees the shrink, but only twice a week—"It's hygiene."

Carla Bruni became what's called an auteur-compositeur. In 1999 the singer Julien Clerc recorded seven of the songs she had written, and in 2003 she recorded her own songs in a grainy whisper on her debut album, Quelqu'un M'a Dit ("Someone told me"). To her surprise, the album was a huge hit, and the following year she won Best Female Vocalist at Victoires de la Musique.

By then she had—scandalously—taken up with Raphaël Enthoven, a philosophy professor several years her junior, who was married at the time to Bernard-Henri Lévy's daughter, Justine. In 2001 they had a son, Aurélien. They broke up in 2007, before she met Sarkozy. They are still close: At the end of lunch, Raphaël stumbles in, an exhausted young man in a gray overcoat. He's just had another son with another woman, and today was the child's bris, with Aurélien in attendance. He leaves, Nati the cook brings a Diet Coke for the first lady to drink out of a can, and we get back to work.

"Through my husband and through what I see, I've seriously raised my consciousness about what's happening in the world, and sometimes it's terrible," Carla says. "These moments of crisis are atrocious—to be in my husband's shoes, or Obama's, is very difficult. But these men are young, and maybe they can manage to make it a better world after this.

"It opened my eyes. Before, I lived in a privileged bubble. My view of the world was constructed in a life where I never saw real action, only listened to a lot of words, and words spoken by people who live in Saint-Germain des Près. There's a big difference between the intellectuals of the Café Flore and people who actually have power, between thought and action. Thought can be free, but action is never free—it has to deal with reality."

In New York last November with Sarkozy to promote her album while he attended the United Nations as head of the EU, she dragged him downtown to lunch with her idol Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson. Later they went to hear Woody Allen play at the Carlyle. "Nicolas doesn't know that he's capable of being relaxed," she says. "He really likes la dolce vita, but he works so hard, we have very little time. That lunch in New York was exceptional—he allowed himself five free hours that day.

"At first when I married Nicolas, I was so scared of saying the wrong thing—that lasted six months. Then I started promoting my album, and when you're doing four interviews a day you can't have a gun to your head every time you speak, so I loosened up a little."

At the Elysée, her office is a ground-floor room hung with a jacquard of rose garlands on pale-blue silk. "What's the pretty statue on the mantelpiece?" I ask. "I have no idea," she says. "Everything in the office belongs to the Elysée." She has no staff of her own—"The status of first lady isn't defined, so anyone who worked for me would have to come out of the taxpayers' money, and I don't want to take up unearned space."

Last October, she began working with Grégoire Verdeaux, Sarkozy's counselor for humanitarian and health matters, to see what she could do. On World AIDS Day, December 1, she was named Global Ambassador for the Protection of Mothers and Children Against HIV/AIDS by the United Nations. Her mandate began January 1. "The fact is that even though treatment is now available, AIDS/HIV is so stigmatized that women are afraid to get help." The issue is personal to her; her older brother, Virginio, died of AIDS at 45, in 2006, after 20 years with the illness. "He was never stigmatized. What I can't stand is that people can be treated, mothers can protect their children from AIDS, but they are too scared of the disease, and the fear of the disease is what I can fight."

She has also established the Fondation Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, to bring culture and education to French children from impoverished neighborhoods. "I can't do much against global poverty or injustice, but I can give money. I'm giving the royalties from my last album to charity, through the Fondation de France. I was able to hand over the first payout of €280,000 to a school in Haiti that had been wiped out by a tide of mud."

Once we get on to poetry, she relaxes into a flow of words. She first heard W. H. Auden's "Funeral Blues" recited as the eulogy in Four Weddings and a Funeral, and set to music his "Lady Weeping at the Crossroads" and "At Last the Secret Is Out" for her second album, No Promises. She had read Yeats since she was a teenager and put his poems to music, along with Emily Dickinson, Christina Rossetti, and Dorothy Parker. And it was while trying to get the rights to Dorothy Parker's "Ballade at Thirty-five" that she learned how much an artist could do to help people directly. "Do you know that when she died in 1967, Dorothy Parker left the rights to all her work to the Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr.?"

There was a little moment when we both saw the possibility for words and music to effect social change.

And then the first lady of France went off to the dentist to have a crown fixed, so it wouldn't fall out at the next state dinner.

source style.com

outfit and her hair at the back is gorgeous! I realise she is taller than Sarkozy but I wish she would ditch the granny shoes!

outfit and her hair at the back is gorgeous! I realise she is taller than Sarkozy but I wish she would ditch the granny shoes!  outfit and her hair at the back is gorgeous! I realise she is taller than Sarkozy but I wish she would ditch the granny shoes!

outfit and her hair at the back is gorgeous! I realise she is taller than Sarkozy but I wish she would ditch the granny shoes!

. I was looking at pictures of her and Zapatero's wife early in the morning and they both looked stunning, it's unfair to compare her with Michelle or Letizia or Zapatero's wife (whose name escapes me right now) or every first lady she keeps meeting.. I'm just glad to see such powerful modern women with great taste and sharp eye for beautiful clothes.. I remember using the 'first lady' (ex. --- is a little too first lady) as a derogatory term for bad taste but that can hardly be applied these days.

. I was looking at pictures of her and Zapatero's wife early in the morning and they both looked stunning, it's unfair to compare her with Michelle or Letizia or Zapatero's wife (whose name escapes me right now) or every first lady she keeps meeting.. I'm just glad to see such powerful modern women with great taste and sharp eye for beautiful clothes.. I remember using the 'first lady' (ex. --- is a little too first lady) as a derogatory term for bad taste but that can hardly be applied these days.