You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Jamie Hawkesworth - Photographer

- Thread starter Creative

- Start date

Legolas

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 12, 2010

- Messages

- 5,353

- Reaction score

- 465

^ He truly is. He owns indoor and outdoor sets in such a personal way that you can almost guess when a new imagine comes from his mastership. Brands and casting directors he usually works with makes him even more interesting to my eyes. I hope he will become real big in a few years.

Melancholybaby

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 25, 2011

- Messages

- 14,152

- Reaction score

- 2,299

Melancholybaby

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 25, 2011

- Messages

- 14,152

- Reaction score

- 2,299

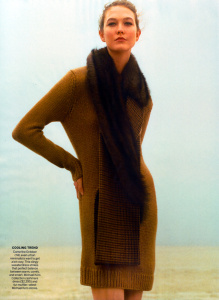

US Vogue January 2015

Character Studies

Photographer: Jamie Hawkesworth

Stylist: Grace Coddington

Models: Tavi Gevinson, Karlie Kloss, Edie Campbell, Imaan Hammam, Miranda Kerr, Caroline Trentini, Banks, Natalie Westling, Margaret Qualley & Kesewa Aboah

Make-Up: Lisa Butler

Hair: Didier Malige

fashionscansremastered.net

Character Studies

Photographer: Jamie Hawkesworth

Stylist: Grace Coddington

Models: Tavi Gevinson, Karlie Kloss, Edie Campbell, Imaan Hammam, Miranda Kerr, Caroline Trentini, Banks, Natalie Westling, Margaret Qualley & Kesewa Aboah

Make-Up: Lisa Butler

Hair: Didier Malige

fashionscansremastered.net

bbofbalenciaga

Member

- Joined

- Jan 26, 2008

- Messages

- 329

- Reaction score

- 1

From the Business of Fashion

The Creative Class | Jamie Hawkesworth, Photographer

BY REBECCA MAY JOHNSON 27 FEBRUARY, 2015

From an unlikely beginning taking pictures of reconstructed crime scenes, Jamie Hawkesworth’s lo-fi, documentary-style approach is quickly making him one of the most important photographers of his generation.

LONDON, United Kingdom — “I remember thinking anything artistic was a bit pointless,” says Jamie Hawkesworth in a Suffolk twang. His formative years in the unglamorous town of Ipswich were not spent yearning to join a fraternity of creative spirits. It was the unlikely setting of a reconstructed crime scene where Hawkesworth — now 27 and shooting campaigns for J.W. Anderson, Loewe and Miu Miu — first picked up a camera with any intent, while studying forensic science in the northern English city of Preston.

But, then, there’s little that is conventional about Hawkesworth, who, despite being a so-called ‘digital native,’ shoots only on film and develops all of his own pictures in a tiny dark room in London’s Shoreditch (which doubles as his office) and has the courage to shoot a global ad campaign by jumping on a train with a “bag of clothes” and a camera.

“Don’t start off with fashion photography. Get out into the world.”

Not destined to spend his life dusting for fingerprints and rooting through rubbish for clues, Hawkesworth found that taking pictures was what he liked most about his forensics course and switched to studying photography. He put together a portfolio, composed of “pictures of my nan, graffiti — the standard,” and for his interview for the photography course brought along Shots from the Hip by Johnny Stiletto — a volume of candid black-and-white images documenting Londoners in the 1980s — an early inspiration.

Though he moved away from forensics, an instinct to document unnoticed characters and details and “find glimmers of hope” in unlikely places became a trait of Hawkesworth’s photographic eye. His first subjects were the teenagers he encountered on his way from Preston North End football stadium, near where he lived, into college, resulting in work his college tutors liked. “A switch went off… I thought to myself, ‘My work will feel relevant because they are a reflection of what’s going on this second. Their clothes, their trainers.’ So I went around Preston with big flash and I’d stop people and say ‘Can I take your portrait?’”

The photographers he admired at college, such as Nigel Shafran (“a massive influence”), show his fascination for the particular, the odd or the beautiful, found in ordinary life. In collections like “Dad’s Office” (1997-1999), “Washing Up 2000” (2000) and “Supermarket Checkouts” (2005), Shafran makes incidental arrangements of everyday objects in shabby rooms vibrate with significance. “His appreciation of banal ordinary objects, so that they’re amplified into something that’s incredible — that stuck with me — the composition, like the way a cup interacts with a book,” enthuses Hawkesworth.

It was Hawkesworth’s images documenting characters and scenes around Preston bus station (an expansive, sculptural, brutalist construction built in 1969), published in the 2010 pamphlet “Preston is my Paris” just after he came to London, that scored Hawkesworth representation by photo agent Julie Brown of MAP. Brown had attempted to buy a copy online, but couldn’t, so asked Hawkesworth to visit the agency to show her and took him on then and there.

Alasdair McLellan’s pictures of youths, too, which Hawkesworth came across at college and which have a naturalistic quality to them, expanded his conception of what fashion photography could be. “Alasdair’s work came up and I was like ‘****, this is really amazing!’ Where it was kind of normal kids — normal guys, that I’ve would have come across in Preston — in fashion.” Bold as brass, Hawkesworth rang up McLellan, asking to be his assistant, and worked on a number of shoots with him.

Hawkesworth was stubborn about safeguarding his integrity and his personal interests, however. “When I got signed at MAP, I said to them, ‘I don’t want to do just fashion, I want to be a documentary photographer — I want to continue that thread.’ I hate it when you go on a photographer’s website and it is divided into fashion, documentary, personal. I think the whole thing should be personal — even commercial work… There shouldn’t be a distinction. So I said to Julie that I want the whole message to be the same.”

One of his first big assignments, in 2012, was to photograph potato pickers in Sweden for The New York Times. He went alone and cycled around with his camera. Soon afterwards, when a set of his images documenting teenagers on solo train trips around the UK caught the eye of French stylist Benjamin Bruno, Hawkesworth shot his first big fashion story for Man About Town magazine. “I got a message from Ben saying, ‘I’ve seen your portraits of kids around England, I’d love for you to shoot an editorial for Man About Town.’”

“Me and Ben got a bag of clothes and went to South Shields near Newcastle…We found a kid — she must have been about 11 years old — and we dressed her head-to-toe in a blue Gucci suit. It was a pinnacle image. Before I was so used to going up to someone and that would be it. But now, there was a French stylist putting these clothes on a kid, elevating the character.”

Through Bruno, Hawkesworth began to work for JW Anderson, shooting the brand’s campaign for autumn/winter 2013. “That was the first fashion advertising I’d done. And it was perfect because we had complete freedom.” The campaign had the same intensity of Hawkesworth’s documentary photography, where subjects simultaneously reveal and conceal themselves, conveying an off-key oddness.

The images worked so well that when Anderson was appointed creative director of Loewe as part of a deal that saw LVMH take a minority stake in his business, he took Hawkesworth along with him to shoot the brand’s campaigns. “We took that language that we were building in JW Anderson to Loewe and M+M Paris came on board — they were already in the picture because of Man About Town [with whom had worked on shoots] — so that was what was so special about it: everybody was on the same page.”

For JW Anderson’s spring/summer 2015 campaign, reminiscent of 1950s horror films, “me and Ben took a bag of clothes to Southwold [in Hawkesworth’s home county of Suffolk] — we had no models — nothing. We walked along the beach and we found a brother and sister, dressed them in the clothes, chucked them in the water and told them to come out — and that’s it. No hair and makeup, nothing.”

Similarly, when he shot a campaign for Trademark, the American sportswear label founded in 2013 by Pookie and Louisa Burch, Hawkesworth tapped his documentary roots. “She got in touch and she said, ‘I’m really inspired by Amish people,’ and I said, ‘Well let’s go to Lancaster and photograph Amish people! Why not just be as literal as that?’ So that’s what we did. I feel that if you go directly to the reference, rather than recreating it, you’re often going to find something incredibly odd.”

Even for his glitziest and largest job to date, for Miu Miu’s Resort 2015 collection, Hawkesworth insisted on travelling alone on the Trans-Siberian Express to take the textural pictures that would sit alongside the campaign’s more traditional images of models shot in a studio. However, he admits to feeling anxious about the demands of shooting for bigger and bigger clients. “With Miu Miu, the night before I went to see the collection, they were shooting a lookbook and there was this elaborate setup of like six flashes and I thought, ‘I couldn’t do that. I wouldn’t even know how to create that environment — I only use daylight.”

But Hawkesworth plans to stick to his documentary instincts. “With fashion photography, if I could give people advice, it’d be not to start off with fashion photography — just do photography — don’t go into the studio and do a test shoot. Get out into the world.”

Pricciao

Active Member

- Joined

- Feb 8, 2010

- Messages

- 4,292

- Reaction score

- 81

Melancholybaby

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 25, 2011

- Messages

- 14,152

- Reaction score

- 2,299

TheoG

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 10, 2013

- Messages

- 4,705

- Reaction score

- 281

J.W Anderson Fall/Winter 2015

Photographer: Jamie Hawkwesworth

Fashion Editor: Benjamin Bruno

Art Direction: Mathias Augustyniak and Michael Amzalag (M/M Paris)

Hair & Makeup Artist: Ellen Walge

Models: Anett Oun, Eliann Tulve, Ingel Kristen, Jette Loona Hermains, Katarina Sarap, Polina Galinskaja, Sonja Tomson & Unknowns

mapltd via gulsah

Photographer: Jamie Hawkwesworth

Fashion Editor: Benjamin Bruno

Art Direction: Mathias Augustyniak and Michael Amzalag (M/M Paris)

Hair & Makeup Artist: Ellen Walge

Models: Anett Oun, Eliann Tulve, Ingel Kristen, Jette Loona Hermains, Katarina Sarap, Polina Galinskaja, Sonja Tomson & Unknowns

mapltd via gulsah

Melancholybaby

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 25, 2011

- Messages

- 14,152

- Reaction score

- 2,299

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 82

- Views

- 15K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)