The World (and Future) of Raf Simons

By Alexander Fury

The Belgian fashion designer Raf Simons lives, at least part of the year, above a flower shop in one of the fancier arrondissements of Paris. His apartment is one of those expected parquet-floored affairs with carved boiseries painted chalk-white, filled with contemporary art. There’s a George Condo painting that makes the sitter look like Beaker from ‘‘The Muppet Show,’’ hung in a space once occupied, perhaps, by a 19th-century academic oil. There are good Picasso ceramics on a gray marble mantelpiece.

An old house, filled with something new. That, and all the flowers, are a neat metaphor for Dior, the fashion house Simons designed for until last October, when, in a surprising turn, he resigned as artistic director of women’s wear. There, Simons disrupted, bringing modern references and even modern art into the storied couture maison. Then, after three and a half years, he was gone.

The apartment came with that Dior job, but remains. Simons’s boyfriend of just over a year is French: They live together here. It’s also convenient, as Paris is where, for the past 21 years, Simons has staged shows for his own, Antwerp*-based men’s wear line. Simons himself is 48 — just. His birthday came a week before his fall show. He’s a winter baby, like Monsieur Dior and Cristóbal Balenciaga. Arguably, of the two, Simons has more in common with the latter, a relentless Modernist with a Spartan aesthetic and a love of complex construction. Balenciaga constantly challenged himself. Balenciaga wrought revolutions. Simons has as well.

However, now Simons has elected to do so not through haute couture clothing for women, but through ready*-to-wear garments for men. It’s the path less ordinary. Which perhaps explains how he worked in relative obscurity for an entire decade through 2005, when he was appointed designer of the German*-based label Jil Sander. Such obscurity comes from the fact that women’s wear outweighs men’s wear in sales, column inches and sheer number of shows — certainly not from Simons’s lack of talent, or, indeed, lack of adulation from the appropriate quarters.

‘‘Men, it is different,’’ Simons says, of the industry, in comparison to women’s wear. ‘‘I find it a pity. It was always an investigation from my side: My brand has never stood for a classic wardrobe, which is what most men’s brands represent. Then they give it a twist, with styling. We are so far evolved . . .’’ he stops, sighs. ‘‘And men’s fashion is still . . .’’ he stops, and sighs again. ‘‘For more than 20 years, I try. I wish it was where women’s fashion is.’’ Meaning he wishes that more designers were like him — willing to ‘‘fashion’’ a new identity for men in the same way they do for women. Not that men’s fashion be subject to the same seasonal upheaval, but that it break out of rigid adherence to the standard sartorial strata of sweater, pants, overcoat, underwear. Men’s wardrobes are ferociously pigeonholed. Simons wants to explore what lies in between. He wants to make clothes we haven’t seen before, not just another white shirt.

In doing so, he has become, arguably, the most important men’s wear designer in the world. He has fundamentally altered the way men dress, and the way men want to dress. He injected men’s wear with cultish youth affiliations before anyone else was doing it, back in the mid-’90s. His clothes then, and now, express something about the world in which we live. Their design evokes socioeconomic mores, notions of value and worth, complex codes of masculinity, youthful rebellion. They challenge the status quo, frequently championing the dispossessed. They’ve influenced entire generations of designers that have followed him, and changed the way his forerunners do their jobs today. He has shifted the landscape of men’s clothing. Even if his impact isn’t perceived, it’s there.

SIMONS COMES FROM a practical background. His father was a soldier; his mother cleaned houses. ‘‘I don’t have a cultural background. My parents weren’t at all, at all, connected to anything you could call cultured,’’ he says, quietly but emphatically. He was born in Neerpelt, Belgium, close to the border of Holland. The population, he says, was about 8,000. ‘‘In our village there was no cinema, no museum, no gallery, no boutique. It wasn’t there. . . . I had no access to things I clearly felt an attraction to. Art, and also fashion.’’

He originally studied industrial design at a university in Genk for five years, graduating in 1991. ‘‘I got frustrated,’’ he says. ‘‘What I was doing after graduation was furniture. I was aware that I had to go to Italy, where there were these producers. Cappellini. Cassina. I just felt that it was out of my reach. I was quite driven. I ended up in a little gallery; they would sell something. But I couldn’t live from it. And my dad would say . . .’’ Simons shrugs. You can picture the conversation.

He had already begun to be enamored of the fashion world, after a friend, the designer Walter Van Beirendonck, took him to Paris to see the work of another young Belgian designer named Martin Margiela. The show, in 1990, took place in a playground; the children played with the models as they strode out. Simons had an immediate emotional connection. ‘‘It was a split second . . . a flash of ‘Ah! It’s not so on the surface, it’s not so glamour and parties.’ It was so different.’’ Simons gets emotional talking about that show even today.

Soon after, Simons designed a few skinny black suits and skinny sleeveless shirts that resembled school uniforms. He made them to impress Linda Loppa, then head of the fashion department at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, in the hope that she would invite the 26*-year*-old to join her course. Those audition garments became Simons’s first collection. Instead of study, Loppa encouraged him to set up a business. ‘‘When I showed it to Linda, she sent me to this agent. . . . I brought it to Milan, literally stuffed into my car. Nothing was planned . . .’’ Simons is still incredulous in relaying the details. ‘‘And he sold to, I don’t remember, seven or nine clients. Japanese clients. Barneys was there the first season! And I just thought ‘How am I going to do this?’ There was no thinking time — I had to create a company.’’

Originally, Simons was to design the line with two female friends. After they dropped out, he concentrated on men’s wear. ‘‘I started to just fit on myself,’’ he recalls. ‘‘It was a real one-man show. That’s how I ended up making 40, 50 garments that were men’s.’’ Simons shrugs, pragmatically. ‘‘It wasn’t the idea to start a men’s collection, the idea was to start a collection. To make garments for a specific audience.’’ That audience was himself — his friends, his generation. Simons once told me he wanted to make clothes for ‘‘kids.’’ Flummoxed, I asked if he meant children’s clothes. He laughed. ‘‘No, me and the kids around me. I was really out to find an audience, no matter how small, who could really feel: ‘This is something I could connect with, something I feel like I can be part of.’ ’’

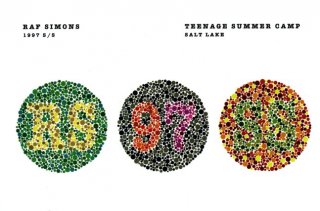

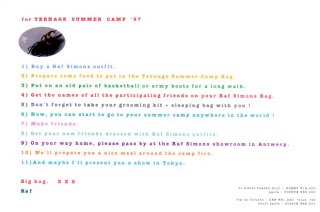

Much of that centered on music, an obsession that Simons has repeatedly articulated in his collections throughout the years. He’s designed clothing inspired by New Order, Joy Division, the Manic Street Preachers. For his fall 1997 runway show, he dressed models as Kraftwerk and played their music as the soundtrack. No one had thought of doing that before, coupling music and men’s wear together to publicly explore their own teenage subcultural affiliations. ‘‘It was nothing to do with fashion, only with music,’’ says Simons. He’s speaking of his teenage years: 13, 14. ‘‘Duran Duran was big and Anne Clark and Depeche Mode and all that kind of stuff. All that was happening when I was going to the clubs, which was great. . . . But no fashion. No fashion the way we now define fashion. No fashion related to fashion designers, fashion brands and fashion houses.’’

If fashion inevitably meets music in Simons’s work, it also meets art. He is an ardent collector. I once saw him walking around the Frieze art fair in London in his own little world, clutching a catalog, eager to buy. The contemporary pieces dotting his apartment are almost a chart for the inspirations and instincts that have powered his career. The Picasso ceramics, for instance, inspired the penultimate women’s wear collection of his tenure at Jil Sander, where Simons worked for seven years, designing the men’s and women’s lines. When he was poached by Dior in 2012, his first collection featured a chiné silk dress woven not with traditional Dior fleurs, but a couture rendition of a spray-painted work by his close friend, the California-based artist Sterling Ruby. Art on your back.

‘‘I wasn’t someone who was so interested in ‘fashion’ before I went to university. I was not obsessed with clothes, at all,’’ Simons says. ‘‘But at quite a young age, I got to see art in a way that triggered interest.’’ When he was 18, he visited the groundbreaking Chambres d’Amis exhibition by the Belgian curator Jan Hoet where more than 50 artists from across America and Europe created works, installed in the homes of private citizens in the city of Ghent. You could buy a train ticket, get a list of the participating houses and visit the art. Simons did. ‘‘And it was mind-blowing,’’ he emphatically states. ‘‘A house, and these people would have had Joseph Beuys in there. I instantly had a very strong attraction to art. I could relate to it. It wasn’t so distant.’’ Simons is wearing a cotton shirt, in thick drill like a workman’s uniform. It’s Yves Klein blue, Pollocked with bleach. It’s another Sterling Ruby piece, not only inspired by, but actively created with the artist. It’s from the collaborative collection Simons designed with him in 2014.

That fall season, the designer shared the label on his clothes with the artist, a recognition of what a true collaboration, an extraordinary fusion of the fashion and art worlds, could look like. Collaborations are normally schlocky, one-season runs, resulting in graphics splattered across clothing and handbags, or spun out cheaply on T-shirts that have all the integrity of rock-band merch. For the Raf Simons/Sterling Ruby collection, however, samples, images and accompanying texts were shunted back and forth across the Atlantic. The final garments looked something like Ruby’s paintings, sprayed with paint and stamped with slogans. Ruby’s work examines notions of masculinity, of urban spaces, of violence. Waste, decay, social anxiety: all ideas that inspire Simons’s designs. For observers, to see a talent like Simons surrender part of his creative authorship to another was exceptional.

Simons speaks Flemish, and his accent is strong and guttural. Dior comes out ‘‘Diorgh.’’ For how much of his life the job consumed for the past few years, he doesn’t bring it up much. On the one hand, because Simons’s men’s wear is now his sole focus; on the other hand, because I suspect he has talked enough about Dior for a lifetime: When I interviewed him after his second cruise show for Dior in New York in 2014, he mentioned how he had just completed 23 consecutive interviews. ‘‘It was really absurd,’’ he murmured.

Yes indeed! Money buys everything in fashionland.

Yes indeed! Money buys everything in fashionland.

heart

heart