NOTE from the moderators:

from newyorker.com

Pixel Perfect

Pascal Dangin’s virtual reality.

by Lauren Collins

For a charity auction a few years back, the photographer Patrick Demarchelier donated a private portrait session. The lot sold, for a hundred and fifty thousand dollars, to the wife of a very rich man. It was her wish to pose on the couple’s yacht. “I call her, I say, ‘I come to your yacht at sunset, I take your picture,’ ” Demarchelier recalled not long ago. He took a dinghy to the larger boat, where he was greeted by the woman, who, to his surprise, was not wearing any clothes.

“I want a picture that will excite my husband,” she said.

Capturing such an image, by Demarchelier’s reckoning, proved to be difficult. “I cannot take good picture,” he said. “Short legs, so much done to her face it was flat.” Demarchelier finished the sitting and wondered what to do. Eventually, he picked up the phone: “I call Pascal. ‘Make her legs long!’ ”

Pascal Dangin is the premier retoucher of fashion photographs. Art directors and admen call him when they want someone who looks less than great to look great, someone who looks great to look amazing, or someone who looks amazing already—whether by dint of DNA or M·A·C—to look, as is the mode, superhuman. (Christy Turlington, for the record, needs the least help.) In the March issue of Vogue Dangin tweaked a hundred and forty-four images: a hundred and seven advertisements (Estée Lauder, Gucci, Dior, etc.), thirty-six fashion pictures, and the cover, featuring Drew Barrymore. To keep track of his clients, he assigns three-letter rubrics, like airport codes. Click on the current-jobs menu on his computer: AFR (Air France), AMX (American Express), BAL (Balenciaga), DSN (Disney), LUV (Louis Vuitton), TFY (Tiffany & Co.), VIC (Victoria’s Secret).

Vanity Fair, W, Harper’s Bazaar, Allure, French Vogue, Italian Vogue, V, and the Times Magazine, among others, also use Dangin. Many photographers, including Annie Leibovitz, Steven Meisel, Craig McDean, Mario Sorrenti, Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia, rarely work with anyone else. Around thirty celebrities keep him on retainer, in order to insure that any portrait of them that appears in any outlet passes through his shop, to be scrubbed of crow’s-feet and stray hairs. Dangin’s company, Box Studios, has eighty employees and occupies a four-story warehouse in the meatpacking district. “I have Patrick!” an assistant to Miranda Priestly, the editor of Runway, exclaims in “The Devil Wears Prada,” but her real-life counterparts probably log as much time speed-dialling Pascal.

Dangin is, by all accounts, an adept plumper of breasts and shrinker of pores. Using the principles of anatomy and perspective, he is able to smooth a blemish or a blip (“anomalies,” he calls them) with a painterly subtlety. Dennis Freedman, the creative director of W, said, “He has this ability to make moves in someone’s facial structure or body. I’ll look at someone, and I’ll think, Can we redefine the cheek? Can we, you know, change a little bit the outline of the face to bring definition? He, on the other hand, will say, ‘No, no, no, it’s her neck.’ He will see it in a way that the majority of people don’t see it.” Dangin salvaged a recent project at W by making a minute adjustment to the angle of a shoulder blade.

The obvious way to characterize Dangin, as a human Oxy pad, is a reductive one—any art student with a Mac can wipe out a zit. His success lies, rather, in his ability to marry technical prowess to an aesthetic sensibility: his clients are paying for his eye, and his mind, as much as for his hand. Those who work with Dangin describe him as a sort of photo whisperer, able to coax possibilities, palettes, and shadings out of pictures that even the person who shot them may not have imagined possible. To construct Annie Leibovitz’s elaborate tableaux—the “Sopranos” ads, for example—he takes apart dozens of separate pictures and puts them back together so that the seams don’t show. (Misaligned windows are a particular peeve.) He has been known to work for days tinting a field of grass what he considers the most expressive shade of green. “Most green grass that has been electronically enhanced, you know, you look at it and you get a headache,” Dangin said recently. He prefers a muted hue—“much redder, almost brown in a way”—that is meant to recall the multilayered green of Kodachrome film.

As renowned as Dangin is in fashion and photographic circles, his work, with its whiff of black magic, is not often discussed outside of them. (He is not, for instance, credited in magazines.) His hold on the business derives from the pervasive belief that he possesses some ineffable, savantlike sympathy for the soul of a picture, along with the vision (and maybe the ego) of its creator. “Just by the fact that he works with you, you think you’re good,” Leibovitz said. “If he works with you a lot, maybe you think, Well, maybe I’m worthwhile.”

His job description is enigmatic. People I asked about him invariably resorted to metaphor: he is a translator, an interpreter, a conductor, a ballet dancer articulating choreographed steps. These analogies, though, don’t account for pursuits that, while probably contributing less to Dangin’s income than wrinkle extermination does, occupy more of his time and intellect. He has become a master printer, “digitally remastering” old negatives and producing fine-art prints for exhibition. “When I see a print, I could probably tell you if it was a Pascal print,” Charlotte Cotton, the head of photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, said. “It’s immaculate, and there’s a kind of richness to the pixellation. It feels like you could almost sink your finger into it.” Books are another love: he is the publisher of SteidlDangin, an imprint of lush art volumes—for instance, a collection of a thousand Philip-Lorca diCorcia Polaroids.

A tinkerer and an autodidact, who started out as a hairdresser, Dangin brings to mind, actually, a building superintendent: he knows how to do a lot of jobs, and those he doesn’t he figures out through trial and error. He is, more than anything, the consigliere for a generation of photographers uncomfortable with, or uninterested in, the details of digital technology. According to Cotton, “Pascal is actually an unwritten author of what is leading the newest areas of contemporary image-making.”

His digital brushstrokes can be as deliberate as Jasper Johns’s or John Currin’s are on canvas, but they are not as consistent—part of Dangin’s skill lies in being able to channel the style, and the fancy, of whatever photographer he is collaborating with. In the spring of 2004, the Prada campaign, shot by Steven Meisel, had a retro, vacationy look—tie-dyed cardigans, hairbands, sailboat prints. Using a Photoshop tool called a smudge brush, Dangin applied extra color to every pixel, giving the pictures—hard and flat, at the outset—a dreamy, impressionistic texture, as if they had been wrought in oil and chalk.

The walls of the third-floor meeting room at Dangin’s headquarters, on West Fourteenth Street, hold magnets in the manner of a refrigerator door. One afternoon in November, grease pencils, in the colors of the rainbow, were stuck, by magnets, to one wall. Nearby, several of Dangin’s assistants were hanging a blueprint—a scaled rendition of the Petit Palais museum, in Paris, where, in September, Patrick Demarchelier will have a retrospective. Dangin was designing the exhibit, from the pictures (many of which he would retouch) and their frames down to the traffic-flow patterns of the museumgoers who would look at them. Dangin would do all of the printing. He was also publishing a companion monograph.

Demarchelier arrived shortly after two. The first order of business was to sift through several notebooks full of photographs to decide which ones to put in the show. Dangin and Demarchelier sat near each other, on two couches. “Ça, ça, ça, ça oui, ça oui, ça non,” Dangin said, marking his choices with a red grease pencil. “Ça on jette, non?” Demarchelier mostly followed the lead of Dangin (“Do you remember that story in French Vogue? Normandy? Wide angle?”), who drew quick, dismissive X’s over the pictures he did not like until the notebook resembled a game of tic-tac-toe.

Once the pictures had been narrowed down, Dangin began explaining to Demarchelier his concept for organizing the show. “Je pensais nuages d’images”—clouds of images—he began. He pointed to the blueprint, explaining that they should show lots of oversized prints, interspersed with thematic groupings of smaller portraits. Dangin had a plan for freestanding frames. “If we build an upside-down T, then we can just insert the print,” he said. “Two feet in Plexiglas and one riser casing. And the steel we can manufacture with José here in the shop.”

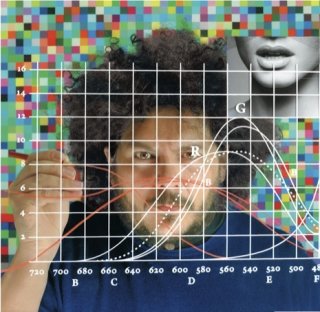

“Patrick, I’m going to show you American Vogue and Seven Jeans,” Dangin said, turning to some current projects. Dangin is on the short side, with a scruffy mustache and finger-in-the-socket frizz. He maintains the hours of a Presidential candidate; lately, he is a little tubbier than he would like. He was wearing, as is his custom, an all-navy outfit: New Balance sneakers, ratty cords, woollen sweater with holes in the armpits. He is not immune to the charms of things—he owns an Aston Martin, along with houses in Manhattan, Amagansett, and St. Bart’s—but, for someone who can pick apart a face in a matter of seconds (he once, apologetically, described his eyes as “high-speed scanners”), he is remarkably free of vanity. “I’m not a stud,” he told me one day. “I don’t have the six-pack chocolate bars, I have a belly. Would I want to look like that? Yes. Am I ever going to achieve that? No. Am I happy? Yes.” He has an earthy streak and a digressive manner of thought, but he issues orders commandingly.

Dangin and Demarchelier walked over to a wall affixed with a dozen color photographs of a famous actress in her late twenties. Demarchelier approached one of them, a closeup of the actress’s face. She was smiling, her head slightly tilted, posed in front of a swimming pool.

“Let’s soften the lines around her mouth,” Demarchelier said, tracing the actress’s nasolabial folds and the flume of her upper lip with the tip of one of the temples of his eyeglasses.

Dangin grabbed a grease pencil off the wall. “The blue in the background is off. We have to make that brighter. Especially for the cover.” By the time they were done, the actress’s face was streaked with black markings, like a football player’s.

They moved on to the jeans campaign. Dangin thought the model’s face was too “crunchy” (meaning that the contrast was high, making her look severe); Demarchelier wanted the denim—a pair of white bell-bottoms—to pop. “Then the only thing is the background here—is it too heavy compared to that one?” Dangin asked, comparing two pictures with the same windswept hills. “See the gradient here? This is a little more black-and-white, this is a little more gray. I prefer that,” he said, indicating the shot with the richer contrast.

Several days later, Demarchelier returned to the studio to continue winnowing images for the show. The conversation turned to which shot to include of another well-known actress.

“I like her in this one, because she looks very natural,” Dangin said.

“Yes,” Demarchelier agreed. “In that other pose, she looks like an actress.”

“But she’s also very good here,” Dangin said, of a shot that showed her partially nude.

This thread is for discussing the impacts of Photoshop and retouching on society/fashion/women/men. We encourage our members to bring in articles (such as the one in post #2) for further discussion. Sample questions that are in the realm of the thread:

Is there too much Photoshop? Why?

Why are even fine publishing houses and well known brands releasing images that are - well - offending to the eye?

What effects can Photoshop have on society?

Images are allowed, of course, but only to illustrate a point, or if it happens to be an enormous flaw on a significant fashion publication (W, Demi Moore).

For more examples and cursory discussion there is another thread in RHI:

Photoshop disasters

from newyorker.com

Pixel Perfect

Pascal Dangin’s virtual reality.

by Lauren Collins

For a charity auction a few years back, the photographer Patrick Demarchelier donated a private portrait session. The lot sold, for a hundred and fifty thousand dollars, to the wife of a very rich man. It was her wish to pose on the couple’s yacht. “I call her, I say, ‘I come to your yacht at sunset, I take your picture,’ ” Demarchelier recalled not long ago. He took a dinghy to the larger boat, where he was greeted by the woman, who, to his surprise, was not wearing any clothes.

“I want a picture that will excite my husband,” she said.

Capturing such an image, by Demarchelier’s reckoning, proved to be difficult. “I cannot take good picture,” he said. “Short legs, so much done to her face it was flat.” Demarchelier finished the sitting and wondered what to do. Eventually, he picked up the phone: “I call Pascal. ‘Make her legs long!’ ”

Pascal Dangin is the premier retoucher of fashion photographs. Art directors and admen call him when they want someone who looks less than great to look great, someone who looks great to look amazing, or someone who looks amazing already—whether by dint of DNA or M·A·C—to look, as is the mode, superhuman. (Christy Turlington, for the record, needs the least help.) In the March issue of Vogue Dangin tweaked a hundred and forty-four images: a hundred and seven advertisements (Estée Lauder, Gucci, Dior, etc.), thirty-six fashion pictures, and the cover, featuring Drew Barrymore. To keep track of his clients, he assigns three-letter rubrics, like airport codes. Click on the current-jobs menu on his computer: AFR (Air France), AMX (American Express), BAL (Balenciaga), DSN (Disney), LUV (Louis Vuitton), TFY (Tiffany & Co.), VIC (Victoria’s Secret).

Vanity Fair, W, Harper’s Bazaar, Allure, French Vogue, Italian Vogue, V, and the Times Magazine, among others, also use Dangin. Many photographers, including Annie Leibovitz, Steven Meisel, Craig McDean, Mario Sorrenti, Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, and Philip-Lorca diCorcia, rarely work with anyone else. Around thirty celebrities keep him on retainer, in order to insure that any portrait of them that appears in any outlet passes through his shop, to be scrubbed of crow’s-feet and stray hairs. Dangin’s company, Box Studios, has eighty employees and occupies a four-story warehouse in the meatpacking district. “I have Patrick!” an assistant to Miranda Priestly, the editor of Runway, exclaims in “The Devil Wears Prada,” but her real-life counterparts probably log as much time speed-dialling Pascal.

Dangin is, by all accounts, an adept plumper of breasts and shrinker of pores. Using the principles of anatomy and perspective, he is able to smooth a blemish or a blip (“anomalies,” he calls them) with a painterly subtlety. Dennis Freedman, the creative director of W, said, “He has this ability to make moves in someone’s facial structure or body. I’ll look at someone, and I’ll think, Can we redefine the cheek? Can we, you know, change a little bit the outline of the face to bring definition? He, on the other hand, will say, ‘No, no, no, it’s her neck.’ He will see it in a way that the majority of people don’t see it.” Dangin salvaged a recent project at W by making a minute adjustment to the angle of a shoulder blade.

The obvious way to characterize Dangin, as a human Oxy pad, is a reductive one—any art student with a Mac can wipe out a zit. His success lies, rather, in his ability to marry technical prowess to an aesthetic sensibility: his clients are paying for his eye, and his mind, as much as for his hand. Those who work with Dangin describe him as a sort of photo whisperer, able to coax possibilities, palettes, and shadings out of pictures that even the person who shot them may not have imagined possible. To construct Annie Leibovitz’s elaborate tableaux—the “Sopranos” ads, for example—he takes apart dozens of separate pictures and puts them back together so that the seams don’t show. (Misaligned windows are a particular peeve.) He has been known to work for days tinting a field of grass what he considers the most expressive shade of green. “Most green grass that has been electronically enhanced, you know, you look at it and you get a headache,” Dangin said recently. He prefers a muted hue—“much redder, almost brown in a way”—that is meant to recall the multilayered green of Kodachrome film.

As renowned as Dangin is in fashion and photographic circles, his work, with its whiff of black magic, is not often discussed outside of them. (He is not, for instance, credited in magazines.) His hold on the business derives from the pervasive belief that he possesses some ineffable, savantlike sympathy for the soul of a picture, along with the vision (and maybe the ego) of its creator. “Just by the fact that he works with you, you think you’re good,” Leibovitz said. “If he works with you a lot, maybe you think, Well, maybe I’m worthwhile.”

His job description is enigmatic. People I asked about him invariably resorted to metaphor: he is a translator, an interpreter, a conductor, a ballet dancer articulating choreographed steps. These analogies, though, don’t account for pursuits that, while probably contributing less to Dangin’s income than wrinkle extermination does, occupy more of his time and intellect. He has become a master printer, “digitally remastering” old negatives and producing fine-art prints for exhibition. “When I see a print, I could probably tell you if it was a Pascal print,” Charlotte Cotton, the head of photography at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, said. “It’s immaculate, and there’s a kind of richness to the pixellation. It feels like you could almost sink your finger into it.” Books are another love: he is the publisher of SteidlDangin, an imprint of lush art volumes—for instance, a collection of a thousand Philip-Lorca diCorcia Polaroids.

A tinkerer and an autodidact, who started out as a hairdresser, Dangin brings to mind, actually, a building superintendent: he knows how to do a lot of jobs, and those he doesn’t he figures out through trial and error. He is, more than anything, the consigliere for a generation of photographers uncomfortable with, or uninterested in, the details of digital technology. According to Cotton, “Pascal is actually an unwritten author of what is leading the newest areas of contemporary image-making.”

His digital brushstrokes can be as deliberate as Jasper Johns’s or John Currin’s are on canvas, but they are not as consistent—part of Dangin’s skill lies in being able to channel the style, and the fancy, of whatever photographer he is collaborating with. In the spring of 2004, the Prada campaign, shot by Steven Meisel, had a retro, vacationy look—tie-dyed cardigans, hairbands, sailboat prints. Using a Photoshop tool called a smudge brush, Dangin applied extra color to every pixel, giving the pictures—hard and flat, at the outset—a dreamy, impressionistic texture, as if they had been wrought in oil and chalk.

The walls of the third-floor meeting room at Dangin’s headquarters, on West Fourteenth Street, hold magnets in the manner of a refrigerator door. One afternoon in November, grease pencils, in the colors of the rainbow, were stuck, by magnets, to one wall. Nearby, several of Dangin’s assistants were hanging a blueprint—a scaled rendition of the Petit Palais museum, in Paris, where, in September, Patrick Demarchelier will have a retrospective. Dangin was designing the exhibit, from the pictures (many of which he would retouch) and their frames down to the traffic-flow patterns of the museumgoers who would look at them. Dangin would do all of the printing. He was also publishing a companion monograph.

Demarchelier arrived shortly after two. The first order of business was to sift through several notebooks full of photographs to decide which ones to put in the show. Dangin and Demarchelier sat near each other, on two couches. “Ça, ça, ça, ça oui, ça oui, ça non,” Dangin said, marking his choices with a red grease pencil. “Ça on jette, non?” Demarchelier mostly followed the lead of Dangin (“Do you remember that story in French Vogue? Normandy? Wide angle?”), who drew quick, dismissive X’s over the pictures he did not like until the notebook resembled a game of tic-tac-toe.

Once the pictures had been narrowed down, Dangin began explaining to Demarchelier his concept for organizing the show. “Je pensais nuages d’images”—clouds of images—he began. He pointed to the blueprint, explaining that they should show lots of oversized prints, interspersed with thematic groupings of smaller portraits. Dangin had a plan for freestanding frames. “If we build an upside-down T, then we can just insert the print,” he said. “Two feet in Plexiglas and one riser casing. And the steel we can manufacture with José here in the shop.”

“Patrick, I’m going to show you American Vogue and Seven Jeans,” Dangin said, turning to some current projects. Dangin is on the short side, with a scruffy mustache and finger-in-the-socket frizz. He maintains the hours of a Presidential candidate; lately, he is a little tubbier than he would like. He was wearing, as is his custom, an all-navy outfit: New Balance sneakers, ratty cords, woollen sweater with holes in the armpits. He is not immune to the charms of things—he owns an Aston Martin, along with houses in Manhattan, Amagansett, and St. Bart’s—but, for someone who can pick apart a face in a matter of seconds (he once, apologetically, described his eyes as “high-speed scanners”), he is remarkably free of vanity. “I’m not a stud,” he told me one day. “I don’t have the six-pack chocolate bars, I have a belly. Would I want to look like that? Yes. Am I ever going to achieve that? No. Am I happy? Yes.” He has an earthy streak and a digressive manner of thought, but he issues orders commandingly.

Dangin and Demarchelier walked over to a wall affixed with a dozen color photographs of a famous actress in her late twenties. Demarchelier approached one of them, a closeup of the actress’s face. She was smiling, her head slightly tilted, posed in front of a swimming pool.

“Let’s soften the lines around her mouth,” Demarchelier said, tracing the actress’s nasolabial folds and the flume of her upper lip with the tip of one of the temples of his eyeglasses.

Dangin grabbed a grease pencil off the wall. “The blue in the background is off. We have to make that brighter. Especially for the cover.” By the time they were done, the actress’s face was streaked with black markings, like a football player’s.

They moved on to the jeans campaign. Dangin thought the model’s face was too “crunchy” (meaning that the contrast was high, making her look severe); Demarchelier wanted the denim—a pair of white bell-bottoms—to pop. “Then the only thing is the background here—is it too heavy compared to that one?” Dangin asked, comparing two pictures with the same windswept hills. “See the gradient here? This is a little more black-and-white, this is a little more gray. I prefer that,” he said, indicating the shot with the richer contrast.

Several days later, Demarchelier returned to the studio to continue winnowing images for the show. The conversation turned to which shot to include of another well-known actress.

“I like her in this one, because she looks very natural,” Dangin said.

“Yes,” Demarchelier agreed. “In that other pose, she looks like an actress.”

“But she’s also very good here,” Dangin said, of a shot that showed her partially nude.

Attachments

Last edited by a moderator:

that was really interesting, especially the part with demarchilier at the beginning. it seems photoshopping can make anyone anything.

that was really interesting, especially the part with demarchilier at the beginning. it seems photoshopping can make anyone anything.

)

)