-

Watch Live! The 2025 VS Fashion Show.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

1970s-1990s The Japanese Avant-garde

- Thread starter softgrey

- Start date

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 411

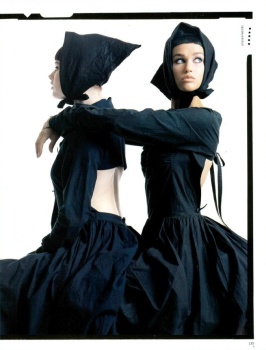

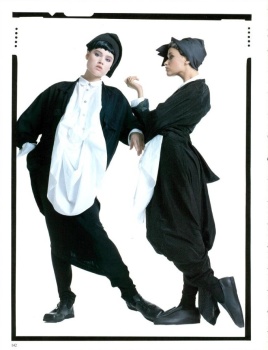

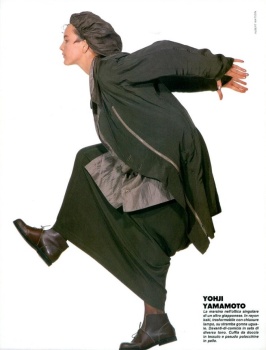

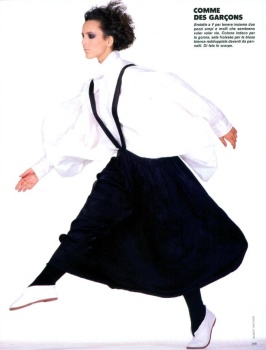

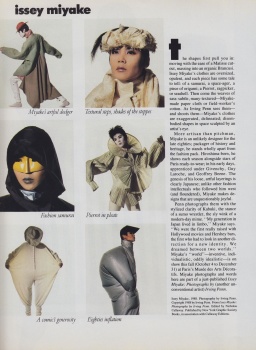

uomoclassico.com

GQ

"Tokyo's Softer Style"

Year: Fall/Winter 1983, September

Models: Bill Shelley, Jack Krenek, Brian Lucas, Scott Connell, Barry Kaufman, John Sommi, Talisa Soto and other two female models

Ph: Rico Puhlmann

Grooming: Bob Fink, Sam McKnight

Fashion: Matsuda, Yohji Yamamoto,Comme des Garçons, Tube, Pashu

GQ

"Tokyo's Softer Style"

Year: Fall/Winter 1983, September

Models: Bill Shelley, Jack Krenek, Brian Lucas, Scott Connell, Barry Kaufman, John Sommi, Talisa Soto and other two female models

Ph: Rico Puhlmann

Grooming: Bob Fink, Sam McKnight

Fashion: Matsuda, Yohji Yamamoto,Comme des Garçons, Tube, Pashu

fashion.fashoff

Member

- Joined

- Jun 6, 2008

- Messages

- 369

- Reaction score

- 5

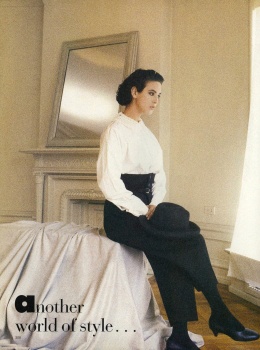

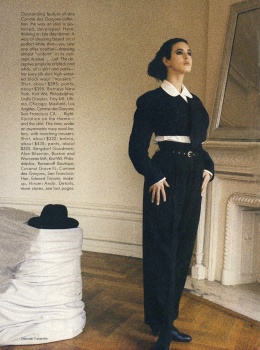

nyc's iconic garage flea market closed recently  many of the vendors have moved across the avenue to a parking lot, but it is not the same. on my last trip to the garage i had to find something special and found this '83 or '84 comme des garcons outfit--i had to buy something and it was between this or a miyake windcoat. this one won!

many of the vendors have moved across the avenue to a parking lot, but it is not the same. on my last trip to the garage i had to find something special and found this '83 or '84 comme des garcons outfit--i had to buy something and it was between this or a miyake windcoat. this one won!

many of the vendors have moved across the avenue to a parking lot, but it is not the same. on my last trip to the garage i had to find something special and found this '83 or '84 comme des garcons outfit--i had to buy something and it was between this or a miyake windcoat. this one won!

many of the vendors have moved across the avenue to a parking lot, but it is not the same. on my last trip to the garage i had to find something special and found this '83 or '84 comme des garcons outfit--i had to buy something and it was between this or a miyake windcoat. this one won!

Hello,

I have seen your post about Issey Miyake zipper suit while researching on the same suit I found for my collection.Do you have any information on this suit?is it rare ?Any info would help.I am a fashion collector.Thanks

I have seen your post about Issey Miyake zipper suit while researching on the same suit I found for my collection.Do you have any information on this suit?is it rare ?Any info would help.I am a fashion collector.Thanks

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,655

- Reaction score

- 5,179

YOHJI YAMAMOTO DEFINES HIS FASHION FASHION PHILOSOPHY

By John Duka

Oct. 23, 1983

Yohji Yamamoto may stand barely five feet tall, but his effect on world fashion in the last two years has been enormous. Many people at the recent Paris showings said he is the best of the new Japanese designers - a distinguished group that includes Rei Kawakubo for Comme des Gar,cons, Issey Miyake and Kansai Yamamoto (no relation). Some say he is the best anywhere. His fans use his first name when they discuss his clothes, a sure sign that a designer has arrived. Fashion experts and retailers are often inclined to exaggerate, but Mr. Yamamoto's influence is hard to dispute.

''When I started designing clothes 12 years ago, I knew there were two ways,'' Mr. Yamamoto, who is 40 years old, said in an interview. ''The first is to work with formal, classical shapes. The other way is to be very casual. That's what I decided on, but I wanted a new kind of casual sportswear that could have the same status as formal clothing. So I use fabrics that are heavy-duty, like army fabrics, or just look heavy-duty, to give the kimono shape a new energy.'' He spoke in English as he sat in his spare white and black showroom near the Les Halles district of Paris. The room, cavernous and brightly lighted, was filled with buyers, trying clothes on from his spring collection.

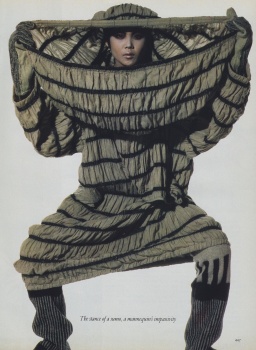

Loosening the Silhouette

What Mr. Yamamoto and the other Japanese designers have accomplished is a general loosening of the female silhouette. This they have done with large, loose-fitting garments, such as jackets with no traditional construction and a minimum of detail or buttons; dresses that often have a straight, simple shape, and large coats with sweepingly oversized proportions. In general, there is a generosity of proportion and size, often with the kimono as a starting point of design, and fabrics that range from fresh cottons to robust linens to heavy wools. All of this came at a time when women's clothes by most traditional designers were moving in the opposite direction, toward a snugger fit and formality.

For fall, one of Mr. Yamamoto's most successful coats is made of a pressed wool in mustard and brown that has the look of great weight but is as light as a raincoat and has no definable shape, except perhaps a generic coat shape. Worn with simple Western day clothes, a pair of black trousers, a black shirt and black heels, it is one of the chicquer designs this season. Moreover, it can be worn during the day or at night.

It is also a good example of the flexibility of Mr. Yamamoto's clothes because it shows that they work best when they are mixed with Western clothing. When the new clothing from Japan is worn on the street in exactly the same way it is shown on the runway, the result often becomes a shapeless heap of fabric. Mr. Yamamoto is aware of that problem.

''I've become very nervous myself about the volume of the Japanese clothing and the kimono shape, so loose and oversized,'' he said. ''If you go too far with a kimono, the final conclusion is just fabric. That is not fashion. The kimono is easy to copy but difficult to make work. It must be done in a technical way, or it becomes sloppy, too big and too baggy. That is why my new collection has shapes that are narrower. I wrapped the body very tight.''

Mr. Yamamoto also continues to break new ground with his men's clothes. His men's spring collection, for example, has sports jackets, in navy or black, that are loose-fitting, with generous, rounded shoulders and gored backs. They are made of 90 percent cotton and 10 percent polyurethane and, as a result, have the stretch of running clothes. There are ankle- length classic trench coats, in tan or black cottons, with shoulders extended by tailoring, not padding. The trousers, some with elastic waists, are loose-fitting. And there are black cotton pullover shirts with zip collars. What strikes one about Mr. Yamamoto's men's clothes is that they would work as well on women.

Men's Shirts, Women's Skirts

A number of women have, in fact, been buying Mr. Yamamoto's men's clothes in New York at the Charivari Workshop, Columbus Avenue at West 81st Street. According to Jon Weiser, who will be adding a 1,900-square-foot Yohji Yamamoto boutique to his next Charivari store, scheduled to open this fall on West 57th Street, women shop the Yamamoto line in his store by moving back and forth between the men's and women's sections, mixing men's shirts with women's skirts.

''I think that my men's clothes look as good on women as my women's clothing,'' said Mr. Yamamoto. ''And more and more women are buying my men's clothes. It's happening everywhere, and not just with my clothes. Men's clothing is more pure in design. It's more simple and has no decoration. Women want that. When I started designing, I wanted to make men's clothes for women. But there were no buyers for it. Now there are. I always wonder who decided that there should be a difference in the clothes of men and women. Perhaps men decided this.''

In the United States and Europe, Mr. Yamamoto's clothing is bought primarily by professionals, largely because of its cost. A blazer usually sells for around $500. But in Japan his biggest fans are students.

''I am designing for my generation,'' he said, ''but in Japan people are very much seeking the old way of life again. Sexual differentiation in clothing is more important. My major customers there are still the unversity students. My generation isn't ready for me yet. They think Yohji is not fashionable enough for them. They will see.''

New York Times

By John Duka

Oct. 23, 1983

Yohji Yamamoto may stand barely five feet tall, but his effect on world fashion in the last two years has been enormous. Many people at the recent Paris showings said he is the best of the new Japanese designers - a distinguished group that includes Rei Kawakubo for Comme des Gar,cons, Issey Miyake and Kansai Yamamoto (no relation). Some say he is the best anywhere. His fans use his first name when they discuss his clothes, a sure sign that a designer has arrived. Fashion experts and retailers are often inclined to exaggerate, but Mr. Yamamoto's influence is hard to dispute.

''When I started designing clothes 12 years ago, I knew there were two ways,'' Mr. Yamamoto, who is 40 years old, said in an interview. ''The first is to work with formal, classical shapes. The other way is to be very casual. That's what I decided on, but I wanted a new kind of casual sportswear that could have the same status as formal clothing. So I use fabrics that are heavy-duty, like army fabrics, or just look heavy-duty, to give the kimono shape a new energy.'' He spoke in English as he sat in his spare white and black showroom near the Les Halles district of Paris. The room, cavernous and brightly lighted, was filled with buyers, trying clothes on from his spring collection.

Loosening the Silhouette

What Mr. Yamamoto and the other Japanese designers have accomplished is a general loosening of the female silhouette. This they have done with large, loose-fitting garments, such as jackets with no traditional construction and a minimum of detail or buttons; dresses that often have a straight, simple shape, and large coats with sweepingly oversized proportions. In general, there is a generosity of proportion and size, often with the kimono as a starting point of design, and fabrics that range from fresh cottons to robust linens to heavy wools. All of this came at a time when women's clothes by most traditional designers were moving in the opposite direction, toward a snugger fit and formality.

For fall, one of Mr. Yamamoto's most successful coats is made of a pressed wool in mustard and brown that has the look of great weight but is as light as a raincoat and has no definable shape, except perhaps a generic coat shape. Worn with simple Western day clothes, a pair of black trousers, a black shirt and black heels, it is one of the chicquer designs this season. Moreover, it can be worn during the day or at night.

It is also a good example of the flexibility of Mr. Yamamoto's clothes because it shows that they work best when they are mixed with Western clothing. When the new clothing from Japan is worn on the street in exactly the same way it is shown on the runway, the result often becomes a shapeless heap of fabric. Mr. Yamamoto is aware of that problem.

''I've become very nervous myself about the volume of the Japanese clothing and the kimono shape, so loose and oversized,'' he said. ''If you go too far with a kimono, the final conclusion is just fabric. That is not fashion. The kimono is easy to copy but difficult to make work. It must be done in a technical way, or it becomes sloppy, too big and too baggy. That is why my new collection has shapes that are narrower. I wrapped the body very tight.''

Mr. Yamamoto also continues to break new ground with his men's clothes. His men's spring collection, for example, has sports jackets, in navy or black, that are loose-fitting, with generous, rounded shoulders and gored backs. They are made of 90 percent cotton and 10 percent polyurethane and, as a result, have the stretch of running clothes. There are ankle- length classic trench coats, in tan or black cottons, with shoulders extended by tailoring, not padding. The trousers, some with elastic waists, are loose-fitting. And there are black cotton pullover shirts with zip collars. What strikes one about Mr. Yamamoto's men's clothes is that they would work as well on women.

Men's Shirts, Women's Skirts

A number of women have, in fact, been buying Mr. Yamamoto's men's clothes in New York at the Charivari Workshop, Columbus Avenue at West 81st Street. According to Jon Weiser, who will be adding a 1,900-square-foot Yohji Yamamoto boutique to his next Charivari store, scheduled to open this fall on West 57th Street, women shop the Yamamoto line in his store by moving back and forth between the men's and women's sections, mixing men's shirts with women's skirts.

''I think that my men's clothes look as good on women as my women's clothing,'' said Mr. Yamamoto. ''And more and more women are buying my men's clothes. It's happening everywhere, and not just with my clothes. Men's clothing is more pure in design. It's more simple and has no decoration. Women want that. When I started designing, I wanted to make men's clothes for women. But there were no buyers for it. Now there are. I always wonder who decided that there should be a difference in the clothes of men and women. Perhaps men decided this.''

In the United States and Europe, Mr. Yamamoto's clothing is bought primarily by professionals, largely because of its cost. A blazer usually sells for around $500. But in Japan his biggest fans are students.

''I am designing for my generation,'' he said, ''but in Japan people are very much seeking the old way of life again. Sexual differentiation in clothing is more important. My major customers there are still the unversity students. My generation isn't ready for me yet. They think Yohji is not fashionable enough for them. They will see.''

New York Times

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,655

- Reaction score

- 5,179

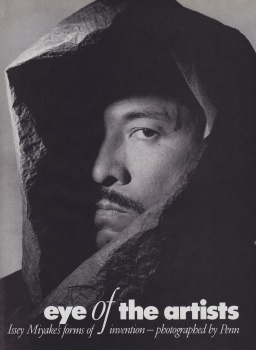

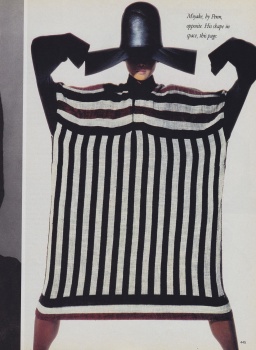

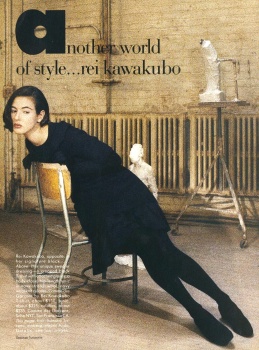

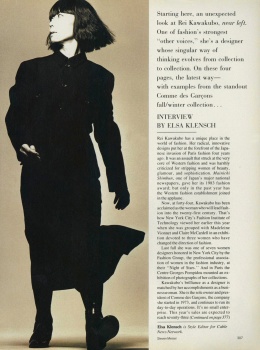

A yen for Yohji

Mon, Mar 13, 2000

When first Issey Miyake, then Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons showed in Paris in the early 1980s, the sensation they caused was quite amazing. Their clothes seemed to be the opposite of dress-making. Miyake was making living geometry, not frocks; Kawakubo's designs were frayed, deconstructed; while Yamamoto's were described by one critic as being "like leftover scraps from an atomic blast [and] call to mind the end of the world".

Dubbed "Hiroshima Chic", this Japanese "invasion" was greeted with equal measures of love and hate. Loved by intellectuals, architects, artists, it was a welcome antidote to the prevailing mores of Power-Suiting and high, high heels. Brenda Polan, then fashion editor of the Guardian recalled that Yamamoto's designs "raised all sorts of questions about conventional beauty, elegance and sexuality".

As the 1980s wore on, however, Yamamoto et al seemed a little irrelevant. The shock had worn off. They'd made their point, we got it, and now it was time to move on. The Belgian school was on hand to adopt the mantle of conceptual dressing, and that appeared to be the end of it. Phaidon's Fashion Book, published in 1998, describes Yamamoto as "legendary", a word that damns with faint praise in an industry that thrives on newness and re-invention. Yet it was in 98 1998 that Yamamoto was re-crowned King of the Catwalks. Perhaps it is our increasingly educated eyes that allow us to see Yamamoto not as an avant-garde artist - although undoubtedly he is - but as a warm and clever human, designing warm, clever and beautiful clothing. Perhaps "BeyondFashion", goes in cycles in the same way that regular fashion does, and it was just a matter of time before Yamamoto's work was re-assessed.

His triumphal return isn't just about rediscovery, though. It is also due to a new levity in his work, a playfulness that was lacking in earlier collections. In Wim s Wenders's documentary, Notebooks on Cities and Clothes, Yamamoto says: "I don't trust the future. I cannot make a commitment to tomorrow." Nine years later in an interview with Vogue, he described the slump between 89 and 97 1989 and 1997 as being an unhappy time "and I suppose I wanted to make ugly things". Die-hard fans probably wouldn't use the word "ugly", but they might concede "difficult". Like the makers of Persian carpets who weave a tiny error into each piece, Yamamoto believes that if you are a human being, you cannot make perfection. His clothes have always been edgy, imperfect, but are now sexier and more feminine; more accessible than has been the case previously.

The past few seasons have been unanimously praised. His 1997 spring/summer collection was a homage to s 1950s Dior and Chanel, and effectively trounced Galliano's slavish copies. While imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, reinterpretation is surely a more honest response: more true to the spirits of Dior or Chanel, who were after all, Moderns. Yamamoto's twisted asymmetric interpretations of old standards were surprising, colourful, romantic and fresh.

This season's collection is deceptively simple, consisting of two different but complementary silhouettes. One is a sort of orphaned New Look. While the bottom half is all fluidity and grace, tops are generally cut close to the body with shrunken sleeves and, despite the occasional smattering of embroidery, have an in-built raggedness, an unfinished quality to them. The alternate look consisted of vaguely s-1930s-style karate pants, loose tunics and dresses in drapey, slithery black satins.

Now, thanks to Nicky Creedon, owner and manger of Havana in Donnybrook, we can expect to see Yamamoto's trademark asymmetry and gentle flaws on these shores for the first time.

Yamamoto's influence can be seen this year in collections as diverse as Nicole Fahri and Calvin Klein, who have both experimented with a form of draping now commonly referred to as Japanese. Donna Karan and Giorgio Armani attended his show. One could argue that without the Yamamoto/Miyake/Kawakubo legacy, the newer generation of designers, Chalayan, Shelley Fox, Olivier Theyskens could not exist. Even Galliano's controversial Hobo Chic collection for Dior this year can trace its lineage back to early Yamamoto. But it is perhaps the sight of normally jaded fashion writers struggling to capture something ephemeral that most reveals the esteem in which Yamamoto is held. Armand Limnander, writing for Vogue.com, referred to him as a master of nuance. His collection this season has variously been described as lyrical, elegant, sinuous, poetic and, of course, that fashion fall-back: fabulous.

I cannot claim to be immune to the hyperbole myself. His spring/summer collection reminded me of William Norwich's epilogue to the 1997 book What Is Beauty?: "A rose is a rose is a rose until you see it fade. Summer is all beach traffic and heat until you feel the first chill of Fall. And these notions about beauty - that beauty results from your loss and desire? Nothing new, nothing new at all. You forget, and then you remember, and call it beauty."

Except that Yamamoto's clothes are not about loss, they are about finding something. They are about those moments, equally as fleeting, when you see beauty in something that hasn't yet happened. The first burst of cherry blossom, for instance, when all else is grey. Something transient, loaded with promise. He says: "I think people like my clothes when they have questions - a sense of doubt. They may want to find something else that interests them. That's when they may be drawn to my clothes. I want my designs to be like a person's face. People's faces change every day. What I am trying to create is something that is alive with human beings."

Irish Times

Mon, Mar 13, 2000

When first Issey Miyake, then Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garcons showed in Paris in the early 1980s, the sensation they caused was quite amazing. Their clothes seemed to be the opposite of dress-making. Miyake was making living geometry, not frocks; Kawakubo's designs were frayed, deconstructed; while Yamamoto's were described by one critic as being "like leftover scraps from an atomic blast [and] call to mind the end of the world".

Dubbed "Hiroshima Chic", this Japanese "invasion" was greeted with equal measures of love and hate. Loved by intellectuals, architects, artists, it was a welcome antidote to the prevailing mores of Power-Suiting and high, high heels. Brenda Polan, then fashion editor of the Guardian recalled that Yamamoto's designs "raised all sorts of questions about conventional beauty, elegance and sexuality".

As the 1980s wore on, however, Yamamoto et al seemed a little irrelevant. The shock had worn off. They'd made their point, we got it, and now it was time to move on. The Belgian school was on hand to adopt the mantle of conceptual dressing, and that appeared to be the end of it. Phaidon's Fashion Book, published in 1998, describes Yamamoto as "legendary", a word that damns with faint praise in an industry that thrives on newness and re-invention. Yet it was in 98 1998 that Yamamoto was re-crowned King of the Catwalks. Perhaps it is our increasingly educated eyes that allow us to see Yamamoto not as an avant-garde artist - although undoubtedly he is - but as a warm and clever human, designing warm, clever and beautiful clothing. Perhaps "BeyondFashion", goes in cycles in the same way that regular fashion does, and it was just a matter of time before Yamamoto's work was re-assessed.

His triumphal return isn't just about rediscovery, though. It is also due to a new levity in his work, a playfulness that was lacking in earlier collections. In Wim s Wenders's documentary, Notebooks on Cities and Clothes, Yamamoto says: "I don't trust the future. I cannot make a commitment to tomorrow." Nine years later in an interview with Vogue, he described the slump between 89 and 97 1989 and 1997 as being an unhappy time "and I suppose I wanted to make ugly things". Die-hard fans probably wouldn't use the word "ugly", but they might concede "difficult". Like the makers of Persian carpets who weave a tiny error into each piece, Yamamoto believes that if you are a human being, you cannot make perfection. His clothes have always been edgy, imperfect, but are now sexier and more feminine; more accessible than has been the case previously.

The past few seasons have been unanimously praised. His 1997 spring/summer collection was a homage to s 1950s Dior and Chanel, and effectively trounced Galliano's slavish copies. While imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, reinterpretation is surely a more honest response: more true to the spirits of Dior or Chanel, who were after all, Moderns. Yamamoto's twisted asymmetric interpretations of old standards were surprising, colourful, romantic and fresh.

This season's collection is deceptively simple, consisting of two different but complementary silhouettes. One is a sort of orphaned New Look. While the bottom half is all fluidity and grace, tops are generally cut close to the body with shrunken sleeves and, despite the occasional smattering of embroidery, have an in-built raggedness, an unfinished quality to them. The alternate look consisted of vaguely s-1930s-style karate pants, loose tunics and dresses in drapey, slithery black satins.

Now, thanks to Nicky Creedon, owner and manger of Havana in Donnybrook, we can expect to see Yamamoto's trademark asymmetry and gentle flaws on these shores for the first time.

Yamamoto's influence can be seen this year in collections as diverse as Nicole Fahri and Calvin Klein, who have both experimented with a form of draping now commonly referred to as Japanese. Donna Karan and Giorgio Armani attended his show. One could argue that without the Yamamoto/Miyake/Kawakubo legacy, the newer generation of designers, Chalayan, Shelley Fox, Olivier Theyskens could not exist. Even Galliano's controversial Hobo Chic collection for Dior this year can trace its lineage back to early Yamamoto. But it is perhaps the sight of normally jaded fashion writers struggling to capture something ephemeral that most reveals the esteem in which Yamamoto is held. Armand Limnander, writing for Vogue.com, referred to him as a master of nuance. His collection this season has variously been described as lyrical, elegant, sinuous, poetic and, of course, that fashion fall-back: fabulous.

I cannot claim to be immune to the hyperbole myself. His spring/summer collection reminded me of William Norwich's epilogue to the 1997 book What Is Beauty?: "A rose is a rose is a rose until you see it fade. Summer is all beach traffic and heat until you feel the first chill of Fall. And these notions about beauty - that beauty results from your loss and desire? Nothing new, nothing new at all. You forget, and then you remember, and call it beauty."

Except that Yamamoto's clothes are not about loss, they are about finding something. They are about those moments, equally as fleeting, when you see beauty in something that hasn't yet happened. The first burst of cherry blossom, for instance, when all else is grey. Something transient, loaded with promise. He says: "I think people like my clothes when they have questions - a sense of doubt. They may want to find something else that interests them. That's when they may be drawn to my clothes. I want my designs to be like a person's face. People's faces change every day. What I am trying to create is something that is alive with human beings."

Irish Times

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,655

- Reaction score

- 5,179

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,346

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,346

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,346

MissMagAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Feb 2, 2005

- Messages

- 26,621

- Reaction score

- 1,346

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 411

yohji trying to somehow follow with karl's talkativeness.

(if I remember rightly, yohji had undergone some intensive english conversation lesson for this)

...

...video wont play in my country~!

softgrey

flaunt the imperfection

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2004

- Messages

- 52,984

- Reaction score

- 411

nani!?

sorry

then I will send the file if you like.

15:05

jodie kidd looks connected with the audience.

Yes- please send the file...

i would appreciate it...

thank you in advance...

YohjiAddict

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 26, 2016

- Messages

- 3,655

- Reaction score

- 5,179

Could you send me the video too? Please

MulletProof

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 18, 2004

- Messages

- 28,845

- Reaction score

- 7,812

Maayan

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 23, 2022

- Messages

- 1,335

- Reaction score

- 2,472

Sure! I'll upload his FW 1993 show in full tomorrow. Do you want me to post it in this thread or make a separate one in this sub-forum?@Maayan I lurked a bit and saw you posted some Koji Tatsuno from the early 90s (1993 specifically- which I had never seen!).. when you have the time, could you please post some of his collections from those years? 🙏

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 220

- Views

- 216K

- Replies

- 49

- Views

- 12K

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 4K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 9K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 8K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)