nytimes.comSeptember 6, 2011, 1:25 pm

Remembering Diana Vreeland

By JESSICA MICHAULT

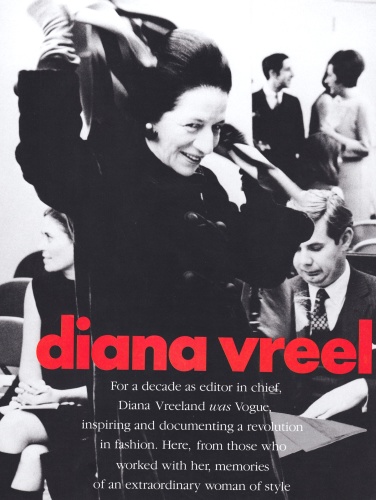

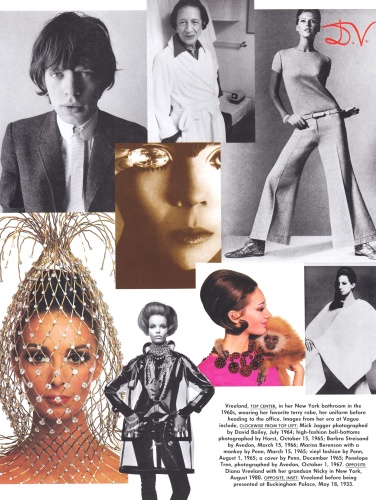

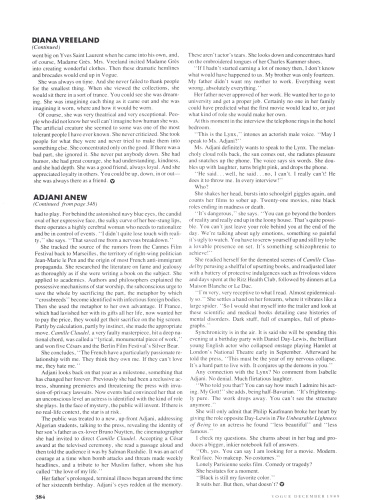

Diana Vreeland in her office as editor in chief of Vogue.Rowland Scherman/Diana Vreeland Archives/From “Diana Vreeland”Diana Vreeland in her office as editor in chief of Vogue.

Diana Vreeland, who died in 1989, is hardly an unknown figure in the worlds of fashion and journalism, with several books and even a critically acclaimed one-woman play having explored her influence as an editor at Harper’s Bazaar and then at Vogue, and later her ground-breaking work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its Costume Institute.

But now, a new documentary that was shown over the weekend at both the Venice and Telluride film festivals has the potential to bring Ms. Vreeland’s story, and a pretty compelling one it is, to a wider audience. “Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel,” is the first of a one-two-three punch that its director, Lisa Immordino Vreeland, has in store for fashionistas over the next year. A coffee table book with the same name will be published by Abrams in October and a special exhibition on Ms. Vreeland, curated by Maria Luisa Frisa and Judith Clark, will get underway next March at the Palazzo Fortuny.

This is apparently the first feature-length documentary film devoted to the life and work of Ms. Vreeland. The photographer and filmmaker Bruce Weber started work on one a few years ago, but it was never completed. Instead, some of the entertaining footage he shot of Ms. Vreeland holding court in her sumptuous New York apartment ended up in his 2001 film, “Chop Suey.”

“The Eye Has to Travel” is a lighthearted yet informative documentary that touches on the fashion editor’s early years, her love of dance and her struggle with her self image before quickly moving onto her time defining the look of both Harper’s Bazaar (from 1936 to 1962) and American Vogue (1962 to 1972). The director smartly allows Ms. Vreeland take the lead in this film, using taped recordings of the editor’s distinctive voice from interviews she did with George Plimpton. With Ms. Vreeland’s voice acting as the framework for the film, the director then turns to interviews with everyone from Ali McGraw (who was her assistant at one point at Harper’s Bazaar) Anjelica Huston, Manolo Blahnik, David Bailey, Penelope Tree, Veruschka, Lauren Hutton and Diana von Furstenberg, to enrich the movie with anecdotal stories and first hand experiences about what it was like to work with Ms. Vreeland

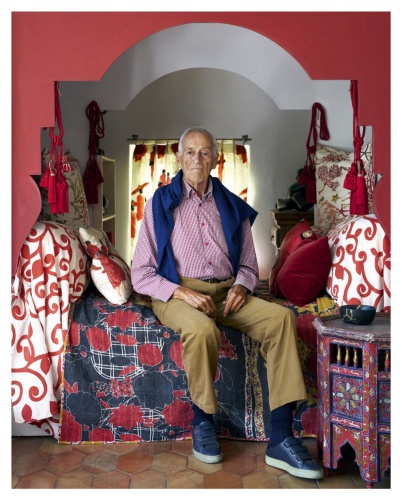

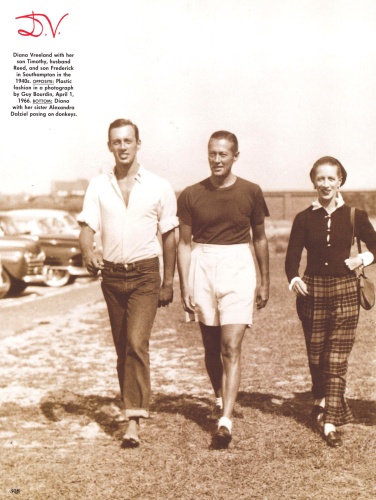

However the more poignant moments are courtesy of the interviews with family members, including her sons Tim and Frecky, and her grandsons Nicky and Alexander (who is the husband of the director). One of the biggest laughs in the film comes from watching the reaction of Ms. Vreeland’s great-granddaughter as she reads some of the editor’s “Why Don’t You” missives from her early years at Harper’s Bazaar.

By the end of the film, you are left with a feeling that Diana Vreeland was a true original: A woman, who embraced change, viewed life in vivid colors and abhorred anything ordinary.

-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Diana Vreeland - Editor

- Thread starter Estella*

- Start date

LittleMsSunshine

Active Member

- Joined

- Jan 24, 2011

- Messages

- 12,969

- Reaction score

- 27

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel [Trailer]

In NY and LA on September 21st, 2012.

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel is an intimate portrait and a vibrant celebration of one of the most influential women of the 20th century, an enduring icon whose influence changed the face of fashion, beauty, art, publishing and culture forever. During her fifty year reign as the "Empress of Fashion," she launched Twiggy, advised Jackie O and coined some of fashion's most eloquent proverbs such as "the bikini is the biggest thing since the atom bomb." She was the fashion editor of HARPER'S BAZAAR where she worked for 25 years before becoming editor in chief of VOGUE followed by a remarkable stint at the Met's Costume Institute where she helped popularize its historical collections.

fashioncopious.typepad.com

In NY and LA on September 21st, 2012.

Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel is an intimate portrait and a vibrant celebration of one of the most influential women of the 20th century, an enduring icon whose influence changed the face of fashion, beauty, art, publishing and culture forever. During her fifty year reign as the "Empress of Fashion," she launched Twiggy, advised Jackie O and coined some of fashion's most eloquent proverbs such as "the bikini is the biggest thing since the atom bomb." She was the fashion editor of HARPER'S BAZAAR where she worked for 25 years before becoming editor in chief of VOGUE followed by a remarkable stint at the Met's Costume Institute where she helped popularize its historical collections.

fashioncopious.typepad.com

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

The trailer on amazon looks fantastic too, this movie is going to be insanely good.

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

I cannot recommend this documentary enough to anybody with an interest in her or fashion during that period. It was just so entertaining and it made me realize how dreadfully boring most magazines are nowadays. There aren't many true "characters" left in our world (or at least in the world of fashion).

HQ poster:

dianavreelandbookandfilm.tumblr.com

HQ poster:

dianavreelandbookandfilm.tumblr.com

Miss Dalloway

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2006

- Messages

- 25,682

- Reaction score

- 994

^ Oh that makes me even more excited to see it, and thanks for the poster. She truly was one of a kind!

BetteT

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 22, 2003

- Messages

- 22,818

- Reaction score

- 111

OK .... I have a question for anyone who knows.

They didn't use her first name in the video, above ... they just call her "Vreeland" ... and I'd like to hear how her first name was pronounced.

I've alway pronounced, as you normally would .... Dye-Anna. But recently someone (who is certainly old enough to know) told me that it was pronounced .... Dee-Anna. Does anyone here know, for sure?

They didn't use her first name in the video, above ... they just call her "Vreeland" ... and I'd like to hear how her first name was pronounced.

I've alway pronounced, as you normally would .... Dye-Anna. But recently someone (who is certainly old enough to know) told me that it was pronounced .... Dee-Anna. Does anyone here know, for sure?

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

BetteT most people in the documentary pronounced her name as Dee-Anna.

happycanadian

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 2, 2005

- Messages

- 8,211

- Reaction score

- 283

or even Dee-Awna.

I just left the movie theatre. saw, "Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel"

i can't remember the last time i saw a documentary bring to life such an extraordinary, fantastical, fiercely original person. she is MARVELOUS in the most extravagant definition of the word.

absolutely and utterly inspiring film.

"Exaggeration is my only reality." - Diana Vreeland

I just left the movie theatre. saw, "Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has To Travel"

i can't remember the last time i saw a documentary bring to life such an extraordinary, fantastical, fiercely original person. she is MARVELOUS in the most extravagant definition of the word.

absolutely and utterly inspiring film.

"Exaggeration is my only reality." - Diana Vreeland

BetteT

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 22, 2003

- Messages

- 22,818

- Reaction score

- 111

Book reviews .... in the Wall Street Journal:

Source: online.wsj.comThe Vreeland Touch

With a dose of exaggeration and fantasy, she ushered fashion through the 'youthquake' of the 1960s

By LAURA JACOBS

Diana Vreeland had the eye of a painter, but not the hand. She had the sudden depth of a poet, but not the verse. She had the historian's fascination with the past, but made her career in the newly hatched now. "I see all sorts of things that you don't see," she once said. "I see girls and I see the way their feet fall off the sidewalk when they're getting ready to cross the street but they're waiting for the light, with their marvelous hair blowing in the wind and their fatigued eyes." It isn't just the physical signature of an era that she could pinpoint—"their feet fall off the sidewalk"—but also its soul: "their fatigued eyes."

Empress of Fashion

By Amanda Mackenzie Stuart

Harper, 419 pages, $35

IDP Films

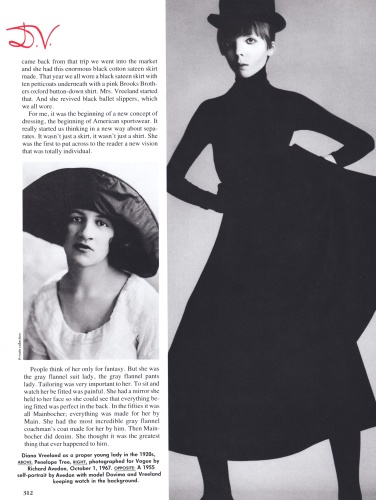

Vreeland (1903-89) was self-made and larger-than-life: a high priestess of fashion, original in vision and fearlessly expressive. Over a span of five decades she held three imperial positions: fashion editor at Harper's Bazaar (1939-62); editor in chief of Vogue (1963-71); and consultant to the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1971-89), where she revamped the sedate dress exhibition of yore into the blockbuster of today. Into an industry that can be superficial and mercenary, she brought the heart of an artist. Vreeland wore her blue-black hair in the style of the Sphinx and remains a looming, almost mythological figure for all who enter the fashion world.

In real life she was diminutive, wore black cashmere and red snakeskin, preferred low-heeled pumps and Roman sandals, and chose totemic jewelry of tusk and tooth. The books that have come steadily since her death in 1989 describe a woman who walked softly on the balls of her feet, yet with a curious camel's sway, who spoke with a tobacco-stained voice of great drama and had a face not pretty but with a glitter in the eye that made it mesmerizing.

The Eye Has To Travel

By Lisa Immordino Vreeland

Abrams, 255 pages, $55

IDP Films

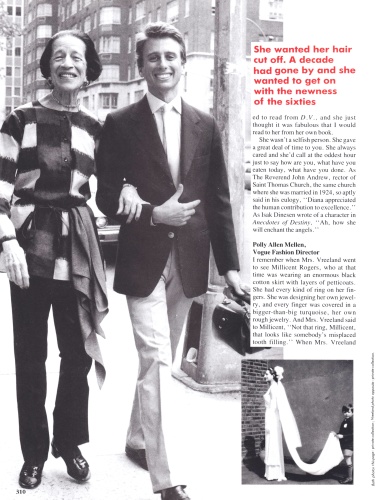

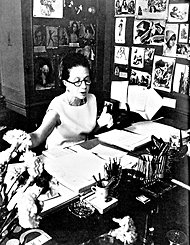

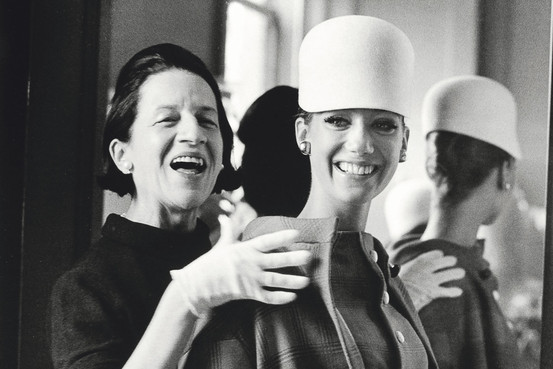

Vreelandiana—the woman's likes, dislikes and disciplines—constitutes a uniquely enduring style sheet. Her first name: pronounced DEE-ana. Her office: scarlet walls, black lacquer and leopard skin. Her lunch: a sandwich of peanut butter and marmalade accompanied by a shot of scotch. Her dollar bills: ironed. The soles of her shoes: polished. "I mean," she once said, "you go out to dinner and suddenly you lift your foot and the soles aren't impeccable . . . what could be more ordinary?" She has a point, if you think about it.

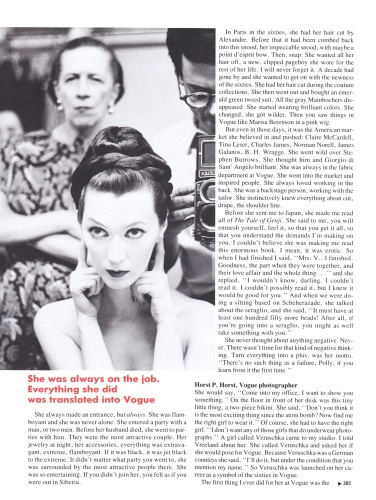

Vreeland herself got the ball rolling in 1980 with "Allure," a compendium of her favorite images accompanied by a text that suggests Auntie Mame on a Grand Tour through the 20th century. On correctness and perfect design: "It's something that survives in the army, the navy, the church—and in royalty." On Poiret's models: "Look at the size of those girls. God, women were big in those days—they're like Percherons entering the ring!" The 1984 memoir "D.V.," a series of conversations edited by George Plimpton and Christopher Hemphill, is equally intimate and worldly, charged with Vreeland's pleasure in the forms and refinements of culture. You needn't care a jot about fashion to find yourself in Vreeland's grip, transported by the events that transported and transformed her—Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, the 1911 coronation of George V, Josephine Baker and her cheetah, Balenciaga's maillots.

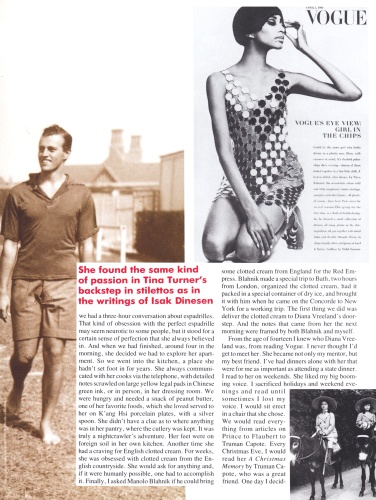

"Full Gallop" (1995), a one-woman show derived from "D.V.," kept Vreelandiana going at full tilt, and 2002's "Vreeland Memos," directives to Vogue staff during the glory-day Sixties, brought the enterprise to a state of weird distillation, with lines like, "I am extremely disappointed that no one has taken the slightest interest in freckles on the models" and "Don't forget the serpent. . . . The serpent should be on every finger and all wrists and all everywhere. . . . We cannot see enough of them." Put these two together and you have the back story for a Vreeland-conceived photo shoot: Eve before the Fall, freckled from gardening.

"Allure" and "D.V." have both been recently reissued, and we have two big books on Vreeland: an authorized biography, "Empress of Fashion" by Amanda Mackenzie Stuart, and an illustrated homage to Vreeland's life called "The Eye Has to Travel," assembled by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, a fashion consultant and wife to Vreeland's grandson Alexander. (A documentary film of the same name, opulent with archival footage and insights from colleagues, models and family members, grew out of this book and was released last September.)

"I loathe narcissism," Vreeland wrote in "Allure," "but I approve of vanity." This is the kind of fine-line distinction that Vreeland made throughout a career that was, when you come down to it, an endless flow of fine-line distinctions—"The green of England is a little deeper than the green of France, a little darker." It is also the kind of thing that is easy to caricature. Both of these books amply depict the scrupulous observation and application that supported Vreeland's strangely definitive airy nothings. One of the triumphs of "Empress of Fashion" is that we begin to understand how Vreeland's valuations of beauty, freshness, grandeur and proportion developed. Ms. Stuart draws us into her subject's indomitable inner life, which, due to the pressure of an exceedingly destructive mother, was formed early with great resolve and concentration. Where in so many biographies the childhood is boring, something to slog through, in this biography it is essential.

Diana Dalziel (pronounced Dee-ELL) was born in 1903, in Paris. Her mother, formerly Emily Key Hoffman, was a demanding society beauty whose family was one of New York's Four Hundred. Her father, Frederick Dalziel, was a tall, elegant, middle-class Englishman who came up the ladder through his marriage. Diana was decidedly not a beauty, having a bit of a squint and a nose she needed to grow into, and her mother viewed her as an embarrassment. That younger sister Alexandra was a showstopper with violet eyes, easygoing and easy to love, made it all the worse, especially when Emily announced to her older daughter, unforgettably: "It's too bad that you have such a beautiful sister and that you are so extremely ugly and so terribly jealous of her. This, of course, is why you are so impossible to deal with."

Ms. Stuart attributes such statements to Emily's own unhappiness and depression. Her constant need for admiration led to extramarital affairs and social scandal and suggests that, for all her beauty, she had few inner resources. Diana, despite a loving father and a warm relationship with her younger sister, was deeply affected by her mother's disdain. "I thought I was the most hideous thing in the world," she said in a 1977 interview. Isolated, contrary, she wasn't thriving, and at age 14 she was asked to leave the Brearley School. It was yet another failure, but one that turned the key to her future, because it opened up time for the study of classical ballet, which she loved.

Music made Diana "forget everything," she would later say: "When I discovered dancing, I learned to dream." Her first dream was to change herself. "I shall please everyone in my appearance & my manner and shall work my hardest in everything I do," she wrote in her diary. And later, "I am only for art and for the arts." Her energies were constructive, and she was soon much admired, first as a debutante and then as a socialite.

One suspects that the narcissism Vreeland loathed was her mother's, and the vanity of which she approved was her own. This played out in the self-improvement plan she set herself—widening her vocabulary, learning French, dressing with uncommon style. This was the first real step on her life's path. "Diana was a vulnerable child," writes Ms. Stuart, "who was saved by the power of her imagination. She deployed it with great intelligence to defend herself against Emily's negative view of her, escaping over and over again to the parallel world of her inner eye in a way that became the basis for much of her later success, which would eventually enable her to challenge conventional ideas about female beauty."

Just as important, Vreeland learned from her father (who chose to believe that his wife wasn't unfaithful, merely a flirt) how not to dwell on the negative, how instead to "bash on." (When it came to Reed Vreeland, her own beloved, beautiful and sometimes philandering spouse, Diana, likewise, didn't dwell.) Ivory-towered, rose-colored, this elevated approach was taken to some extremes in Vreeland's adulthood. She herself would use the word "faction" to describe her brand of truth: fact made more interesting—more true, in a way—with a dose of exaggeration and fantasy, or in other words fiction. Faction was what she would so brilliantly bring to the pages of Vogue during her reign there from 1963 to 1971: poppies blown up into cyclops monsters by Irving Penn; a fashion shoot along the western border of land purported to be Eden ("Paradise Found"); an interracial love affair in the chill snow country of Japan ("The Great Fur Caravan"). Vreeland wasn't frivolous. She believed that "fashion must be the most intoxicating release from the banality of the world."

Ms. Stuart does a meticulous job of separating faction from fact. Readers versed in "D.V." will be surprised to learn that Vreeland didn't grow up in Paris but in good old New York City. And while it is true she went from Brearley to ballet at 14, this wasn't the end of her formal education, as she liked to claim; Vreeland continued her schooling quite successfully at two smaller academic institutions. As for the launch of her career, she wasn't discovered by Carmel Snow while out dancing in a white lace Chanel but was plucked by Snow from the offices of Town & Country in 1936, where she was already working on the society page. Vreeland-the-storyteller was a romantic. She used faction to magnify a moment or event, to create a sense of auspicious timing or swift fate.

When the editorship of Vogue came to Vreeland in 1963, she was, Ms. Stuart shows, uniquely prepared to usher it through the joie de vivre and cultural upheaval of the decade—an era she would capture with the perfect coinage, "youthquake." Vreeland's love and study of dance had given her not just the discipline and imagination (for her they went hand in hand) to carry a storied magazine on her shoulders and in her head; it gave her an open mind about bodies, especially the female body, and the issues of freedom, adornment and sexuality that attended especially closely in the Sixties. In 1964, when Vogue got flak for printing a Courrèges design that showed a belly button, Vreeland's response was: "What are we talking about, for Christ's sake—pleasing the bourgeoisie of North Dakota? We're talking fashion—get with it!"

Reading through all these bits of Vreelandiana, one keeps coming back to her singular expressive power. Full of hyperbole, epiphany and risk, her sweepingly bold way of speaking allowed her to make direct and brilliant connections: "The jet and penicillin—that's really where our world began." And she saw in the same way she spoke. Vreeland was the first editor in America to publish a photograph of the young unknown Mick Jagger. It was 1964, and British Vogue had rejected the photo by David Bailey. Vreeland pounced on it. Why? Because of Brigitte Bardot. "Her lips," she explained, "made Mick Jagger's lips possible." Can one say she wasn't right?

Vreeland was doing for her readers what she had done for herself, pushing them to take control, to culture up, to live a more self-created life. In the final phase of her career, which took her from two dimensions to three, she became a full-fledged impresaria. Vreeland had always maintained that Diaghilev's Ballets Russes was the only real avant-garde she had ever known—"It all had to do with line"—and his dictum "astonish me" was a perfect fit with her position at the Met's Costume Institute. She brought in millions of people and millions of dollars, even as her sort of showmanship—a poeticized zeitgeist that sometimes wowed at the expense of precision—didn't go over with scholars. At any rate, it was too late for Vreeland to change her style.

She wasn't interested in what was ordinary, conventional or cut and dried. Her rallying cry was, "Give 'em what they never knew they wanted." Leafing through "The Eye Has to Travel," with its reproductions of Vreeland's ebullient fashion spreads and unexpected photo essays—on white swans and still whiter Arabian horses, on the painted face of the geisha and the Chimbu woman's mourning dress of withered leaves—one sees just how audaciously she gave, how transcendence and transfiguration were bound up in her vision. "There's only one thing in life," Vreeland says on the last page of "D.V.," "and that's the continual renewal of inspiration." Renewal is the operative word, almost spiritual in its effect. As Ms. Stuart reveals, this twilight wisdom came to Vreeland when she was a suffering girl. Out of it she made a world extraordinaire.

—Ms. Jacobs writes on fashion design and history for Vanity Fair magazine.

Last edited by a moderator:

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

*Amazon.co.ukDiana Vreeland Memos: The Vogue Years: Correspondence from the Vogue Years

Hardcover: 288 pages

Publisher: Rizzoli International Publications (15 Oct 2013)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0847840743

ISBN-13: 978-0847840748

A look behind the scenes at Diana Vreeland’s Vogue, showing the legendary editor in chief in her own inimitable words. When Diana Vreeland became editor in chief of Vogue in 1963, she initiated a transformation, shaping the magazine into the dominant U.S. fashion publication. Vreeland’s Vogue was as entertaining and innovative as it was serious about fashion, art, travel, beauty, and culture. Vreeland rarely held meetings and communicated with her staff and photographers through memos dictated from her office or Park Avenue apartment. This extraordinary compilation of more than 250 pieces of Vreeland’s personal correspondence—most published here for the first time—includes letters to Cecil Beaton, Horst P. Horst, Norman Parkinson, Veruschka, and Cristobal Balenciaga and memos that show the direction of some of Vogue’s most legendary stories. These display Vreeland’s irreverence and her characteristically over-the-top pronouncements and reveal her sharpness about the Vogue woman and what the magazine should be. Photographs from the magazine illustrate the memos, showing her imagination, prescience, and exactitude. Each chapter is introduced by commentary from Vogue editors who worked with her, giving readers a truly inside look at how Diana Vreeland directed the course of the magazine and fashion world.

Last edited by a moderator:

VogueGirl8910

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 14, 2008

- Messages

- 47,957

- Reaction score

- 8,878

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

Similar Threads

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)