The Vogue Arabia cover feature got uploaded to British Vogue this morning. Basically she's saying 'sowwyy fashunn' and want all her deals back. I hope Carine and Kors won't give her any work!

Also the idea of setting up cubicles backstage sounds like a logistical nightmare but then again I'm not a model so can't imagine what it's like.

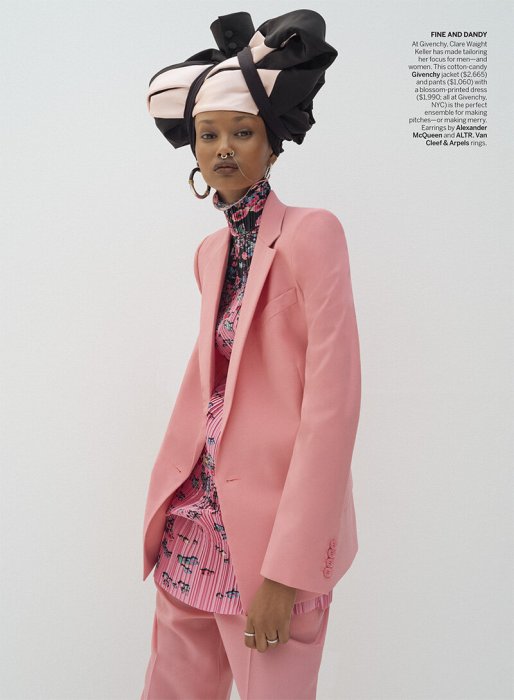

Via Vogue.co.uk

“I Thought I Hadn’t Done Enough To Showcase The Hijab In A Proper Way”: Halima Aden On Her Decision To Quit Modelling, And What’s Next

After an abrupt departure from the world of fashion in 2020, Halima Aden is back, and starring on the cover of

Vogue Arabia. She talks to editor-in-chief Manuel Arnaut about what prompted her decision to step back from modelling, therapy, and why she’s busier than ever.

BY

MANUEL ARNAUT

4 May 2023

There are not many places in the world like Chefchaouen, a tiny village stacked between the mountains of northwest Morocco where blue is the reigning colour. Dating back to 1471, every little alley is coated with paint and layers of history, immediately transporting you to a real-life postcard, where a serene but powerful energy takes over. As a guide explains, blue was painted on the walls, floors and steps to represent the colour of the sky, and to connect the city to heaven and God.

It is not a coincidence that this small village in north Africa was selected as the backdrop for

Halima Aden’s first cover shoot after unexpectedly exiting the fashion industry in 2020. Like the location that surrounds us, when I meet Aden, she is serene and warm, but there’s definitely a sense of power behind her gaze and inviting smile.

The relationship between

Vogue Arabia and Aden is long, dating back to 2017, when, for our 4th edition, we invited the new face to become the first hijab-wearing star to appear on the cover of

Vogue. The project was met with acclaim, with hijabi women around the world feeling represented on the front of a publication with the impact of

Vogue. Unapologetic and fearless since day one, the Somali refugee came onto our radar the year prior, after making a splash at the Miss Minnesota USA competition, where she was the first contestant to participate in the event wearing a burkini and a veil. And while today there might be awareness around modest dressing and the women who wear it – from US politician

Ilhan Omar to Olympic fencer Ibtihaj Muhammad – it was not the case back then.

In the years, that followed the model enjoyed incredible success: trips around the globe, glitzy red carpets, and glamorous fashion weeks. But, in 2020, for Aden, something felt terribly wrong. She found herself at a crossroads where her faith, her

mental health, and her career were no longer compatible. To announce this, the model went straight to Instagram, posting dozens of consecutive stories featuring her past fashion shoots, campaigns, and covers, where she felt that her hijab was not respected, nor her identity as a Muslim woman.

“During the pandemic I was too hard on myself. And the truth is that 2019 was the busiest year of my career,” Aden reflects. “To give you insight, in one month I had 45 flights, and not one day to spend with my family. I’m grateful, because that was the reason why my platform grew the way it did. But then, when the pandemic happened, everything paused, and I’m someone that likes to always keep busy. During lockdown, there were no distractions, so I had to be at one with my own mind and that was tough. I thought that I hadn’t done enough when it comes to showcasing the hijab in a proper way; I could no longer relate to this identity of wearing a hijab. Towards the end of my career, in my photoshoots, my hijab became more adventurous… It was very experimental, and I confess I also had a part to play in that. Nobody forced me to put jeans on my head instead of a traditional veil, to do a shoot being fully decked out with jewellery, and very sexy even though it was modest…”

Besides the personal and religious beliefs that made her exit the industry, Aden also underlines the importance of discussing the working conditions of models in general, whether they are hijabi or not. “This is not just a discussion around Muslim girls. It’s about how we should treat all models,” she points out. “I think that a big part of the reason why I quit was the lack of privacy backstage. I was mortified early on in my career when I realised some shows had just clothing racks to separate the girls from the public, from male photographers, from the people bringing food... For me, as a newbie, I had my own box, literally one box just for myself… It was awkward and just didn’t feel right,” she explains. “When you come from the refugee community I hail from, the one thing I can’t stand is when the perks are not applied to everybody else. When the other models came to me to ask if they could use my small dressing box I remember thinking, ‘Why can’t they just create a covered space for all of us?’ Even Walmart has changing rooms; one for the girls and one for the guys... Of course, we never complained, because we are too scared to make a fuss and be replaced. If you speak up, you are labelled difficult.”

Although Aden’s decision to call out the fashion industry was received with excitement by the general media, I ask if she regrets the way her message was delivered. After all, the stylists, publications, clients and editors she singled out on her posts were also the people giving her a platform, helping her to build a career when she was an unknown model. And many of them made an effort to protect Aden the best way they knew or could, trying to navigate the complexities of the hijab, creating special dressing boxes, allowing her to be accompanied by a chaperone, and so on. “My message resonated with people because I was honest, but I was also young. If I could go back, I wouldn’t have delivered it on Instagram. I really wouldn’t have,” she answers. “I do feel bad, and I feel like I could have been gentler. But fashion is a cruel business to be a part of and sometimes you just have to say it like it is. You can’t be so scared because other people are not afraid to tell you, ‘You’re not good enough, you’re doing this wrong.’ Tell me the last time a model went on Instagram to quit or to call out the industry... That same night,

The Guardian, BBC World News… all these major outlets were writing my story.”

Now we see Aden’s history being written again, but on her own terms, and right in front of our eyes. Wearing a delicate white Chanel lace dress (with an underbody and a classic veil, of course), she is posing next to a beautiful Moroccan door – blue, like everything else around us. If modelling is like riding a bicycle, she clearly didn’t forget how to pose for the camera. To return to this place of confidence and control, Aden tells me that she spent the intervening years working on her mental health, “unpacking things”, and doing weekly therapy sessions. “I always thought, ‘Oh, I don’t need that.’ It turns out that the people who say this are the ones that need it the most. Now, I’m just at a different place in my life, where I feel very protected, I feel very loved and cared for. I’m really going at my pace, which wasn’t the case as a model.”

On the topic of mindfulness, Aden is quick to acknowledge that visiting a therapist is a luxury that not everyone has access to, especially the younger generations. Therefore, she is collaborating with Snapchat for the project Club Unity, which encourages Gen Z voices to open up about their own mental health journeys, empowering them to embrace this important aspect of their lives. “Honestly, it is a privilege speaking to a therapist, and it is unfortunate many people can’t afford it.

“In my case, it was never the option. Under the influence of my mom, the solution was always to run back to God, pray your five daily prayers, fast, wake up at 2am to journal. But at one point, I felt like I needed somebody who could understand everything that I was going through,” Aden continues. Besides classic therapy, she underlines the importance of becoming a more mindful society, something she believes that can also be achieved through bonding with family and community. “When I was growing up in a refugee camp in Kenya, I might have been just a child, but I remember the laughter – I remember my mom being so stressed, but at the same time, so full of light and joy, and the bliss on her face. And this is in a refugee camp…” she shares. “I realised that because there was such a strong sense of community, there really wasn’t a need for therapy. Now, in America, we are very isolated, and I feel we don’t do enough of a good job of discussing where we’re at.”

While modelling took a backseat when it comes to Aden’s career, she is busier than ever, working on different projects that make her eyes sparkle. Still in fashion, in 2024, she will be releasing a ready-to-wear collection in collaboration with a Jordanian and Muslim entrepreneur, a project she prefers not to reveal too much of for now. There is also an ongoing partnership with the Turkish modest e-tailer

Modanisa, where Aden doubles down as global spokesperson in addition to designing turbans and headscarves since 2017. “They were one of the brands who reached out and really supported me when I decided to quit,” she remembers. “This past year was amazing, as our collection sold out right away. It was exciting to be in the creative seat, fully working on vision boards, casting of models, campaign concepts, packaging, and even the small notes that go with each purchase… It made me appreciate all the work behind a brand even more.”

The two other projects Aden is excited to reveal showcase her range as creative and a humanitarian. In partnership with Vita Coco, she wrote a children’s book targeting communities being supported by the coconut water brand, which recently built 30 classrooms in the Philippines for youngsters with limited resources. When Aden visited the locations, she realised she didn’t want to come back empty handed, and started typing three versions of an inspiring and empowering children’s book.

For the big screen, following Aden’s initial cinema experience producing the 2019 film

I Am You by Afghan director Sonia Nassery Cole, there’s already a movie script registered at the Writers Guild of America. “I will tell my agent to send you a copy, so you see I’m not joking,” she laughs. “I noticed that there are gaps in the movie industry, and there are not many Muslim writers, showcasing what a modern Muslim woman is like. It’s easy for people to have misconceptions of Muslim females when they only see on the news very extreme examples of women in a hijab. We are not oppressed. We have dreams and ambitions, and we make mistakes. We’re human, we’re not perfect, we’re flawed. We are so misunderstood… I’m aware I’m not in Hollywood, but I know what I’ve been able to accomplish in fashion, and the truth is that nothing is impossible. So, you must dream, you have to believe in yourself – and I do believe in myself. I have this newfound confidence in my ability and my story, and film is the perfect medium to share it with the world.”

Perhaps the work that still takes centre stage in Aden’s universe is her role in inspiring refugees. Born in the Kakuma camp in Kenya, where she resided until she was relocated to Minnesota at seven years old, the journey of Halima Aden is a success story that inspires millions of other people obliged to flee their home countries. Just at Kakuma alone there are 185,000 displaced people, from 14 different nations. When I ask her what it really means to be a refugee, she stops and takes a couple of seconds to gather her thoughts. “That’s a hard one… But I would say scars and smiles,” she throws. “The reason why I say scars and smiles is there’s a lot of trauma that comes with being a refugee. A lot of the work that I was doing in therapy was unpacking some of those experiences.” It is in this context that Aden has been collaborating with the platform

RefuSHE, “a community for refugee girls by refugee girls.” And while she describes the project, I notice she mentions the word hope more than once in the same sentence. But how do you feed this “hope” when, as a refugee, you have barely anything physical to eat, I wonder.

“I think that when people have lost it all, they cling tight to hope. They cling tight to that one day. Maybe, if I pray hard enough, I will have that one opportunity that's going to change our lives,” Aden concludes. “Only 1 per cent of refugees get to leave the camps and go to a developed country like America. Only 1 per cent. But if there is that 1 per cent chance, people are going to have hope, they will continue to pray, and to daydream about a better future. The reality is that no parent would put their child on a boat, to cross an ocean, if it wasn’t an extreme situation. Sometimes, when people have experienced the worst that life has to offer, they become grateful and appreciative for the tiniest win of everyday life. The way that we, in America, don’t necessarily always appreciate.”

).

). . You can try to be more critical, responsible, resistant or thoughtful about the level of consumerism it involves but anyone remotely participant will at least be okay or used to seeing certain price tags, and then to pay large sums of money for something the average person or anyone barely making ends meet (most people in most countries) will find extravagant and even cruel. For her to overlook the very premise of fashion (consumerism usually manifested through reckless spending and display) and modeling (basically finalizing the goal of the product - its sale - with your body and face) one could think she's just extraordinarily naive and ignorant, but I'd say she was fooled into thinking it could be about her and that her opportunism could outsmart an entire industry. To this day, she's still confined to her role in fashion and whatever minimal mark she was allowed to have there, she still has to be the 'hijab-wearing model' in order to receive publicity.. so much for "quitting" modeling thinking your values came first.

. You can try to be more critical, responsible, resistant or thoughtful about the level of consumerism it involves but anyone remotely participant will at least be okay or used to seeing certain price tags, and then to pay large sums of money for something the average person or anyone barely making ends meet (most people in most countries) will find extravagant and even cruel. For her to overlook the very premise of fashion (consumerism usually manifested through reckless spending and display) and modeling (basically finalizing the goal of the product - its sale - with your body and face) one could think she's just extraordinarily naive and ignorant, but I'd say she was fooled into thinking it could be about her and that her opportunism could outsmart an entire industry. To this day, she's still confined to her role in fashion and whatever minimal mark she was allowed to have there, she still has to be the 'hijab-wearing model' in order to receive publicity.. so much for "quitting" modeling thinking your values came first.