-

The F/W 2026.27 Show Schedules...

New York Fashion Week (February 11th - February 16th) London Fashion Week (February 19th - February 23rd) Milan Fashion Week (February 24th - March 2nd) Paris Fashion Week (March 2nd - March 10th)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

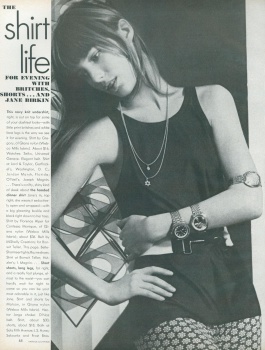

Jane Birkin

- Thread starter Estella*

- Start date

PARIS, July 16 (Reuters) - British-born actress and singer Jane Birkin, a 1960s wildchild who became a beloved figure in France, has died in Paris aged 76.

The French Culture Ministry said the country had lost a "timeless Francophone icon".

Local media reported she had been found dead at her home, citing people close to her. Birkin had a mild stroke in 2021 after suffering heart problems in previous years.

The French Culture Ministry said the country had lost a "timeless Francophone icon".

Local media reported she had been found dead at her home, citing people close to her. Birkin had a mild stroke in 2021 after suffering heart problems in previous years.

MulletProof

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 18, 2004

- Messages

- 29,005

- Reaction score

- 8,303

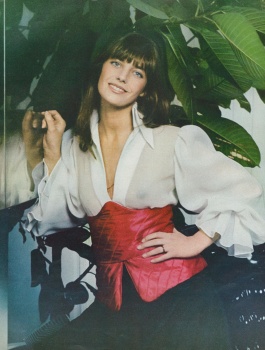

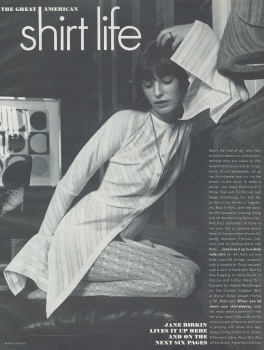

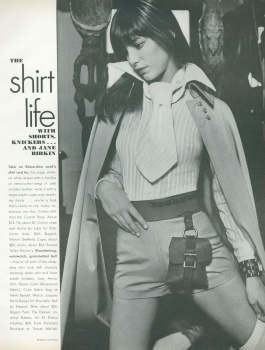

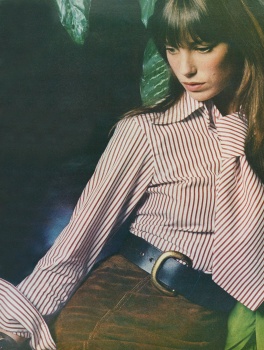

^ Lovely!. I remember years ago (like.. maybe 15 years ago?!!) when I thought I had seen all of Jane's photos that ever made it to the internet lol, and I was probably not wrong, but glad to see more material has been brought in ever since, especially after her passing.. there are so many photos and looks I had never seen (like the one above, and all the times she brought her Portuguese basket to evening events  ). She was pretty on the outside but always showed such a pragmatic and sensible take on life and all its concepts (justice, beauty, love, art, even death) that it came across as modest and relatable and it made her even more beautiful and fascinating.

). She was pretty on the outside but always showed such a pragmatic and sensible take on life and all its concepts (justice, beauty, love, art, even death) that it came across as modest and relatable and it made her even more beautiful and fascinating.

Still sad she's gone, I hope she had time to finish the rest of her memoirs.

*eta: justaguy, would you be able to merge this thread with the older (giant) one, please??

). She was pretty on the outside but always showed such a pragmatic and sensible take on life and all its concepts (justice, beauty, love, art, even death) that it came across as modest and relatable and it made her even more beautiful and fascinating.

). She was pretty on the outside but always showed such a pragmatic and sensible take on life and all its concepts (justice, beauty, love, art, even death) that it came across as modest and relatable and it made her even more beautiful and fascinating.Still sad she's gone, I hope she had time to finish the rest of her memoirs.

*eta: justaguy, would you be able to merge this thread with the older (giant) one, please??

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

MulletProof

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 18, 2004

- Messages

- 29,005

- Reaction score

- 8,303

Yay this thread’s been reopened! now if someone could fix the title and merge it with the other one.. 🧎♀️

Glad to see new pictures of her and in superb quality.. I miss her, I still can’t believe she’s gone 💔.. she embodied multiple industries, eras, interests and sides of the human experience all in one, there really isn’t anyone with some level of fame that comprehends that.. most are too busy being their brand.

Glad to see new pictures of her and in superb quality.. I miss her, I still can’t believe she’s gone 💔.. she embodied multiple industries, eras, interests and sides of the human experience all in one, there really isn’t anyone with some level of fame that comprehends that.. most are too busy being their brand.

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

D

Deleted member 116957

New/Inactive Member

- Joined

- Apr 4, 2009

- Messages

- 13,695

- Reaction score

- 15,837

alwaysademo

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- May 25, 2024

- Messages

- 775

- Reaction score

- 1,485

A thoughtful New Yorker article on Jane:

By Anahid Nersessian

September 15, 2025

In Agnès Varda’s film “Jane B. par Agnès V.,” from 1988, a nearly forty-year-old Jane Birkin, dressed in jeans, a white T-shirt, and a tweed blazer, her messy brown hair pinned back, sits in front of the Eiffel Tower and dumps out the contents of her purse. The purse, which she helped design, is named for her: it’s the Birkin bag, by Hermès, one of the most famous accessories in the world. Inside are loose papers, notebooks, a tube of Maybelline’s Great Lash mascara, a copy of Dostoyevsky’s “The Gambler,” a Swiss Army knife, pens and markers, a roll of tape. “Well,” Birkin says, in heavily accented French, “did you learn anything about me from seeing my bag?” Then a grin: “Even if we reveal everything, we don’t show much.”

Throughout “Jane B.,” Varda draws attention to the elusiveness of her subject. Birkin, a British-born actress and singer best known, then as now, for the raunchy pop songs she recorded with her lover Serge Gainsbourg, comes across as both open and enigmatic, singular in a way that is hard to parse. Her beauty is undeniable, but its borders are vague. Proud of her own eccentricity, she is also shy and awkward, with the voice of a little girl—hushed, rushed, and airy. Varda dresses her up as Joan of Arc, Caravaggio’s Bacchus, the Virgin Mary, a cowboy, and a flamenco dancer, as if to suggest that Birkin’s mystery is itself a symbol, one as important to modern culture as Renaissance painting and the mother of Christ.

Birkin, who died in 2023, had “it”: an undefinable, unmistakable glamour that shifts our collective sense of what’s cool, or at least of what’s worth paying attention to. Easily mingling English reserve and European sensuality, she had a sweetness that set her apart from contemporaries such as the bombshell Brigitte Bardot or the edgier Anna Karina. “She wasn’t a hippie,” the journalist Marisa Meltzer writes in her new biography, “It Girl: The Life and Legacy of Jane Birkin” (Atria), “but rather a rising star from the upper class,” someone who radiated privilege even when she dressed down. One of the first celebrities to be regularly photographed in her everyday clothes, Birkin was an early icon of street style, traipsing around Paris in sneakers and rumpled sweaters, wicker basket in hand. The outfits could be easily mimicked and therefore easily marketed. Today, when social-media influencers praise “the French-girl look”—wispy bangs, minimal makeup, bluejeans, marinière tops—the look they have in mind is hers.

Birkin, Meltzer writes, was “nonchalance personified.” If this was not exactly an illusion, neither was it the whole story. A lifelong depressive, Birkin often thought about—and at least once attempted—suicide. Her diaries, two volumes of which have been published, reveal a wonderful writer, lyrical and self-lacerating. They also reveal her struggles with the costs and compromises of the It Girl role, how it left her feeling as though she had—as she puts it in Varda’s film—“no exceptional talents” to offset her fast-fleeting youth. What Birkin did have is je ne sais quoi, to her misfortune as much as to her advantage. After all, being famous for your ineffable qualities is perilously close to being famous for no reason.

Jane Mallory Birkin was born in London on December 14, 1946. Her father, David Birkin, came from a well-heeled military family. During his time in the Royal Navy, he helped support the French Resistance, smuggling members of de Gaulle’s government-in-exile between Dartmouth and the Brittany coast. Judy Campbell, Jane’s mother, was a film and theatre actress, a close collaborator of Noël Coward’s, and enough of a celebrity that, according to Birkin, when she and David married their wedding was filmed by a news crew. Although she worked steadily until her death, in 2004, the demands of raising three children—Jane, along with her older brother, Andrew, and her younger sister, Linda—took a toll on Campbell’s career. “My father swore that she could go on as an actress,” Jane recalled. “Promises, promises!”

All three Birkin siblings went into the arts. Andrew became a screenwriter and director, Linda a sculptor. Their childhood was happy, though Jane had the requisite dismal experience at an English boarding school, where she lasted three years before her parents let her come home. In the early pages of her diaries, begun when she was ten, she is serious and introspective. “Am I really alive?” she wonders. “Is this all a dream?” Some days later: “I feel fed up, I don’t want to dance, don’t want to do anything. It’s horrid, everything is horrid. I feel like a lump of coal on the side of the road, a very busy road.”

At fifteen, Jane became smitten with a middle-aged man named Alan, an “arty type” who lived across the street from her, in Chelsea. David Birkin let his daughter spend time at Alan’s apartment, certain he could see everything from the family’s balcony. Then Alan moved. “He invited me to his place, a basement,” Jane would say later.

I’d had too much red wine to drink for dinner—he drank whiskey and we ate ratatouille. He lay beside me and tried to get on top of me. I said it was the wrong time of the month, and he said it didn’t matter. I found that a bit disgusting and I ran away. . . . I went to my room and swallowed all the Junior Aspirin that I’d saved just in case. My sister found me at four in the morning, deathly pale. She told Ma. Stomach pump. Ma slapped me and was right to do so. Ever since I’ve always hated whiskey and ratatouille.

Afterward, Birkin wrote a poem called “Suicide Lost,” in which she presents herself as “a child who’s frightened to live . . . a person who can’t find a way out.” If Alan was the first arty, abusive man to whom she found herself drawn, he would by no means be the last.

After her suicide attempt, Birkin’s parents sent her to a finishing school in Paris, where she learned some French and hung around Versailles, the Louvre, and the Jeu de Paume. “I like poor Toulouse-Lautrec,” Birkin wrote in her diary. “He’s sad and the vulgarity and patchiness of life comes out in his painting.” In 1964, she returned to England and decided to pursue acting, winning a role, in Graham Greene’s play “Carving a Statue,” as “a deaf-and-dumb girl who, after being seduced by a doctor is squashed by a bus and left for dead.” Her next part was in a musical comedy titled “Passion Flower Hotel.” The film’s composer, John Barry, had written the music for two James Bond films; he would go on to score nine more, and to win five Academy Awards for his work on movies including “Out of Africa” and “Dances with Wolves.” Birkin was seventeen; Barry was thirty. When she turned eighteen, they married.

The relationship was a disaster from the start. In Birkin’s account, Barry was cruel, a philanderer who taunted her with his pursuit of other women, leaving her to wallow in what she called “the silence of loneliness in the rebuke of the quietness of unanswered questions.” Meanwhile, Birkin’s star was on the rise. In 1966, she made a memorable appearance in Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blow-Up,” as one of two models who roll around naked with a hot-shot photographer. She landed a small profile in Vogue, which praised her “wide, wondering hazel eyes.” Already, there was a growing distance between Birkin’s image and her interior; under her pillow, she kept a stick of eyeliner, so that her husband wouldn’t see her “tiny, piggy eyes” when he woke up. One night, when Barry came home bragging that he’d had dinner with an attractive blond actress, Birkin smashed raw eggs into the sink and scratched her legs until they bled.

On April 8, 1967, Kate Barry was born. Birkin adored the baby but was tortured by her husband’s coldness. “People do want me,” she wrote in her diary. “I want every bit of it, I want it all. But I really only want it from John because I love him and it seems he is destroying me as he has everybody else.” When Kate was three months old, Birkin received a phone call from her father. Barry had been seen in a hotel, in Rome, with another woman. With a bassinet in one hand and a suitcase in the other, Birkin left her marital home and moved in with her parents. “Lie awake / And dream of stopping,” one of her poems from this period reads. “Dream of ending / Dream of dying.”

How did this fragile young woman become “The Emancipated Venus of the New Age,” as the Belgian magazine Ciné Télé Revue dubbed her in 1969? Birkin was desperate for love, and when she got it she blossomed. A year earlier, in May, 1968, she had met Gainsbourg, a famous singer-songwriter and an established playboy, on the set of the romantic comedy “Slogan.” He was recovering from a breakup with Brigitte Bardot, Birkin was recovering from the breakup of her marriage, and all of France was about to be thrown into the heady days of a student uprising, when huge labor strikes brought the country to a standstill. Neither Gainsbourg nor Birkin was impressed. “He was Russian!” Birkin told Le Monde, in 2013. “It seemed anecdotal compared to the October Revolution.”

The Birkin of the Gainsbourg years is the one we know best, the It Girl of Meltzer’s title. According to Elinor Glyn, who popularized the concept in her 1927 novel, “It,” the quality couldn’t be reduced to mere sex appeal. “The most exact description,” she told an interviewer, is “some curious magnetism, and it always comes with people who are perfectly, perfectly self-confident . . . indifferent to everything and everybody.” In the blockbuster silent film “It,” based on Glyn’s novel, Clara Bow plays Betty Lou Spence, a spirited shopgirl who attracts the attention of her wealthy boss when she’s seen on the town in a chic flapper look reworked from a shabby day dress. Slicing off her sailor collar to create a deep-V neckline and attaching some fake flowers to her hip, Betty Lou marches out her tenement apartment and into a fancy restaurant with her head high, pointedly unbothered by the looks she gets from upper-crust diners.

Birkin projected just this sort of youthful insouciance. Skinny and flat-chested, with big teeth and a galumphing walk, she was no pinup and knew it. She styled herself, Meltzer notes, “in contrast to the quintessential French women of the time”: instead of hip-hugging dresses and high heels, there were Repetto flats, denim cutoffs, soft knits, and crocheted crop tops. The look was improvisational yet elegant, a perfect match for shifting social and sartorial trends. If a young Parisienne in the nineteen-twenties could feel liberated by the loose tailoring and comfortable fabrics of Coco Chanel’s new suits, Birkin’s generation wanted something even less restrictive. “I don’t care much about expensive couture clothes,” Birkin told Women’s Wear Daily, in 1969. “I like the floppy look of Saint Laurent.”

And yet Birkin was far from the self-reliant gamine embodied by Clara Bow. According to Meltzer, Birkin seemed unable “to cultivate much sense of self outside of her relationships with men and her children.” At first, life with Gainsbourg was idyllic. Shacked up on the Rue de Verneuil with Kate and another baby, Charlotte, on the way, they became a bohemian power couple. They took Kate, dressed in Baby Dior, to casinos and bought a house in Normandy, where they went boating with the children. Being Birkin’s partner was an ego boost for Gainsbourg, who had never been conventionally handsome and whose heavy drinking and smoking had aged him prematurely. (He had his first heart attack at forty-five and would die of another, at sixty-two.) “When they tell me I’m ugly,” he crows on his song “Des Laids des Laids,” from 1979, “I laugh softly, so as not to wake you up.”

Gainsbourg doted on Birkin and their girls, but he also went through periods of being, in Birkin’s words, “systematically drunk”—and, at times, violent. “I was too abusive,” Meltzer quotes him saying. “I came home completely pissed, I beat her. When she gave me an earful, I didn’t like it: two seconds too much and bam!” Birkin’s diaries suggest a man who was insecure, moody, and controlling:

Everything revolves around him, his films, his records, his life, the rest mustn’t change, neither the children nor me, orders at table, hard words, and unfair on Kate, this masculine superiority that dominates everything, that arranges everything, the house must be just so and no other way, the children are growing but they mustn’t change. He’s like that. And if there’s a revolt, I’m the one who’s sick or changed, or good for nothing.

“When I’m depressed,” she admitted, “I sometimes want to die very much and by his hand. Why not? I’m so tired of the complication of living.”

In 1979, Birkin began an affair with the filmmaker Jacques Doillon, who was thirty-five to her thirty-two—an invigorating change from Gainsbourg, eighteen years her senior. The new relationship promised something less complicated, more harmonious. “I want a house full of sunlight,” she wrote, “nothing forbidden, no more orders.” She took Kate and Charlotte to a hotel, leaving Gainsbourg behind but not yet formalizing things with Doillon. The two men were “like complementary bookstands,” she wrote. “Let go one and you slide, let go both and you fall. . . . So there I am, stubbornly living my life as best I can without either.” This period of independence was short-lived. Soon, she and Doillon moved in together, and in 1982 their daughter, Lou, was born. Gainsbourg sent her a gift basket full of baby clothes, from “Papa Deux.”

It was around this time that Birkin made her most celebrated contribution to fashion. On an Air France flight, she found herself seated next to Jean-Louis Dumas, the chief executive of Hermès. As Birkin struggled to stow her signature wicker basket, spilling its contents, Dumas suggested that she needed a new bag. This prompted Birkin to complain that she couldn’t find one that both looked good and held all her stuff. She recalled sketching a roomy, wedgelike design on the back of an air-sickness bag. Dumas took the design to his studio, tweaked it, and the Birkin was born. Current models can sell for more than four hundred thousand dollars; in July, at Sotheby’s, the prototype went for ten million. It was the second most valuable fashion item ever sold at auction, behind only Dorothy’s slippers.

The arrival of the Birkin bag marked the beginning of a more creatively fulfilling period for its namesake. She continued to work in film, earning César nominations for Best Actress for her work in Doillon’s “La Pirate” (1984) and Best Supporting Actress in “La Belle Noiseuse” (1991), Jacques Rivette’s drama about a painter who becomes infatuated with a younger woman, to the chagrin of his wife and former muse, played by Birkin. Her most significant achievement, however, was a series of concerts, in 1987, at the Bataclan, the Paris theatre that would become the site of a terrorist attack, in 2015. For Birkin, the performances represented a passage between her gangly, passive youth and a more confident middle age, a transition she announced, characteristically, through her style. “I cut my hair off like a boy, I wore men’s clothes,” she said later. “I only wanted people to hear the music and the words. It was fantastic.”

For Birkin, getting older meant a kind of invisibility, a prospect that at once unnerved and elated her. At a Lincoln Center screening of “Jane B. par Agnès V.,” in 2016, she explained—in that same girlish voice—that she had agreed to do the film because she’d felt that, on the eve of turning forty, she could now be convincing as “any old person,” no longer defined by her famous face. It’s an extraordinary remark. For one thing, the whole purpose of the movie is to offer a portrait of Birkin as her specific, unprecedented self. More to the point, the Jane Birkin who appears before Varda’s camera is inimitably stunning, and the one who sat on the stage at Lincoln Center—nearly seventy years old, in a gray frock coat, hair unbrushed, spectacles perched on the edge of her nose—was just as magnetic, with a gravity and a self-possession that have only enhanced her charm.

Meltzer is not quite sure how to handle this phase of Birkin’s life. On the one hand, she paints her as a Nancy Meyers-ish heroine, channelling Diane Keaton in slacks and blazers, “ready to focus back on her own self as she ages.” There is a sentence that describes Birkin’s choice to forgo plastic surgery as “an almost anti-capitalist way of rebelling against gender norms.” On the other hand, she seems to consider Birkin’s aging as a process of subtraction. But, if the elder Birkin became “less classically pretty,” she also lived long enough to prove that her beauty was something enduring, even primordial.

For evidence, see Charlotte Gainsbourg’s 2021 documentary, “Jane by Charlotte,” a sequel of sorts to Varda’s film. Critics were mixed on it, with the Times calling it “defiantly insular.” Meltzer writes, “Charlotte said the theme of the film was a daughter looking for her mother, which is accurate but doesn’t mean it was an artistic success.” In reality, “Jane by Charlotte” is a cinematic essay on beauty, as Gainsbourg uses her camera to stroke, squeeze, and caress Birkin’s body, lingering on her gnarled hands, the play of light over her cheekbones, her feet in Converse sneakers.

Gainsbourg shoots her mother as if she were a medieval sculpture of a sad but radiant saint whom the passage of time only ennobles. She shoots her, in other words, as a human being who has something most human beings do not—an accent of grace. Singing onstage at New York’s Beacon Theatre or puttering around her house in Brittany, Birkin appears shorter and stouter, with thin lips and sunspots. She moves slowly, in recovery from treatment for leukemia and from an immense trauma—the death, perhaps by suicide, of her daughter Kate, in 2013. When you look at her, you experience a sense not of loss but of revelation. She is a person of substance, of mettle hard-earned. This is how lovely she always was, or, rather, was always going to be. ♦

Published in the print edition of the September 22, 2025, issue, with the headline “Saving Face.”

How Jane Birkin Handled the Problem of Beauty

She possessed a mysterious charisma and a seemingly effortless sense of style. Both obscured her relentless, often painful search for meaning.By Anahid Nersessian

September 15, 2025

In Agnès Varda’s film “Jane B. par Agnès V.,” from 1988, a nearly forty-year-old Jane Birkin, dressed in jeans, a white T-shirt, and a tweed blazer, her messy brown hair pinned back, sits in front of the Eiffel Tower and dumps out the contents of her purse. The purse, which she helped design, is named for her: it’s the Birkin bag, by Hermès, one of the most famous accessories in the world. Inside are loose papers, notebooks, a tube of Maybelline’s Great Lash mascara, a copy of Dostoyevsky’s “The Gambler,” a Swiss Army knife, pens and markers, a roll of tape. “Well,” Birkin says, in heavily accented French, “did you learn anything about me from seeing my bag?” Then a grin: “Even if we reveal everything, we don’t show much.”

Throughout “Jane B.,” Varda draws attention to the elusiveness of her subject. Birkin, a British-born actress and singer best known, then as now, for the raunchy pop songs she recorded with her lover Serge Gainsbourg, comes across as both open and enigmatic, singular in a way that is hard to parse. Her beauty is undeniable, but its borders are vague. Proud of her own eccentricity, she is also shy and awkward, with the voice of a little girl—hushed, rushed, and airy. Varda dresses her up as Joan of Arc, Caravaggio’s Bacchus, the Virgin Mary, a cowboy, and a flamenco dancer, as if to suggest that Birkin’s mystery is itself a symbol, one as important to modern culture as Renaissance painting and the mother of Christ.

Birkin, who died in 2023, had “it”: an undefinable, unmistakable glamour that shifts our collective sense of what’s cool, or at least of what’s worth paying attention to. Easily mingling English reserve and European sensuality, she had a sweetness that set her apart from contemporaries such as the bombshell Brigitte Bardot or the edgier Anna Karina. “She wasn’t a hippie,” the journalist Marisa Meltzer writes in her new biography, “It Girl: The Life and Legacy of Jane Birkin” (Atria), “but rather a rising star from the upper class,” someone who radiated privilege even when she dressed down. One of the first celebrities to be regularly photographed in her everyday clothes, Birkin was an early icon of street style, traipsing around Paris in sneakers and rumpled sweaters, wicker basket in hand. The outfits could be easily mimicked and therefore easily marketed. Today, when social-media influencers praise “the French-girl look”—wispy bangs, minimal makeup, bluejeans, marinière tops—the look they have in mind is hers.

Birkin, Meltzer writes, was “nonchalance personified.” If this was not exactly an illusion, neither was it the whole story. A lifelong depressive, Birkin often thought about—and at least once attempted—suicide. Her diaries, two volumes of which have been published, reveal a wonderful writer, lyrical and self-lacerating. They also reveal her struggles with the costs and compromises of the It Girl role, how it left her feeling as though she had—as she puts it in Varda’s film—“no exceptional talents” to offset her fast-fleeting youth. What Birkin did have is je ne sais quoi, to her misfortune as much as to her advantage. After all, being famous for your ineffable qualities is perilously close to being famous for no reason.

Jane Mallory Birkin was born in London on December 14, 1946. Her father, David Birkin, came from a well-heeled military family. During his time in the Royal Navy, he helped support the French Resistance, smuggling members of de Gaulle’s government-in-exile between Dartmouth and the Brittany coast. Judy Campbell, Jane’s mother, was a film and theatre actress, a close collaborator of Noël Coward’s, and enough of a celebrity that, according to Birkin, when she and David married their wedding was filmed by a news crew. Although she worked steadily until her death, in 2004, the demands of raising three children—Jane, along with her older brother, Andrew, and her younger sister, Linda—took a toll on Campbell’s career. “My father swore that she could go on as an actress,” Jane recalled. “Promises, promises!”

All three Birkin siblings went into the arts. Andrew became a screenwriter and director, Linda a sculptor. Their childhood was happy, though Jane had the requisite dismal experience at an English boarding school, where she lasted three years before her parents let her come home. In the early pages of her diaries, begun when she was ten, she is serious and introspective. “Am I really alive?” she wonders. “Is this all a dream?” Some days later: “I feel fed up, I don’t want to dance, don’t want to do anything. It’s horrid, everything is horrid. I feel like a lump of coal on the side of the road, a very busy road.”

At fifteen, Jane became smitten with a middle-aged man named Alan, an “arty type” who lived across the street from her, in Chelsea. David Birkin let his daughter spend time at Alan’s apartment, certain he could see everything from the family’s balcony. Then Alan moved. “He invited me to his place, a basement,” Jane would say later.

I’d had too much red wine to drink for dinner—he drank whiskey and we ate ratatouille. He lay beside me and tried to get on top of me. I said it was the wrong time of the month, and he said it didn’t matter. I found that a bit disgusting and I ran away. . . . I went to my room and swallowed all the Junior Aspirin that I’d saved just in case. My sister found me at four in the morning, deathly pale. She told Ma. Stomach pump. Ma slapped me and was right to do so. Ever since I’ve always hated whiskey and ratatouille.

Afterward, Birkin wrote a poem called “Suicide Lost,” in which she presents herself as “a child who’s frightened to live . . . a person who can’t find a way out.” If Alan was the first arty, abusive man to whom she found herself drawn, he would by no means be the last.

After her suicide attempt, Birkin’s parents sent her to a finishing school in Paris, where she learned some French and hung around Versailles, the Louvre, and the Jeu de Paume. “I like poor Toulouse-Lautrec,” Birkin wrote in her diary. “He’s sad and the vulgarity and patchiness of life comes out in his painting.” In 1964, she returned to England and decided to pursue acting, winning a role, in Graham Greene’s play “Carving a Statue,” as “a deaf-and-dumb girl who, after being seduced by a doctor is squashed by a bus and left for dead.” Her next part was in a musical comedy titled “Passion Flower Hotel.” The film’s composer, John Barry, had written the music for two James Bond films; he would go on to score nine more, and to win five Academy Awards for his work on movies including “Out of Africa” and “Dances with Wolves.” Birkin was seventeen; Barry was thirty. When she turned eighteen, they married.

The relationship was a disaster from the start. In Birkin’s account, Barry was cruel, a philanderer who taunted her with his pursuit of other women, leaving her to wallow in what she called “the silence of loneliness in the rebuke of the quietness of unanswered questions.” Meanwhile, Birkin’s star was on the rise. In 1966, she made a memorable appearance in Michelangelo Antonioni’s “Blow-Up,” as one of two models who roll around naked with a hot-shot photographer. She landed a small profile in Vogue, which praised her “wide, wondering hazel eyes.” Already, there was a growing distance between Birkin’s image and her interior; under her pillow, she kept a stick of eyeliner, so that her husband wouldn’t see her “tiny, piggy eyes” when he woke up. One night, when Barry came home bragging that he’d had dinner with an attractive blond actress, Birkin smashed raw eggs into the sink and scratched her legs until they bled.

On April 8, 1967, Kate Barry was born. Birkin adored the baby but was tortured by her husband’s coldness. “People do want me,” she wrote in her diary. “I want every bit of it, I want it all. But I really only want it from John because I love him and it seems he is destroying me as he has everybody else.” When Kate was three months old, Birkin received a phone call from her father. Barry had been seen in a hotel, in Rome, with another woman. With a bassinet in one hand and a suitcase in the other, Birkin left her marital home and moved in with her parents. “Lie awake / And dream of stopping,” one of her poems from this period reads. “Dream of ending / Dream of dying.”

How did this fragile young woman become “The Emancipated Venus of the New Age,” as the Belgian magazine Ciné Télé Revue dubbed her in 1969? Birkin was desperate for love, and when she got it she blossomed. A year earlier, in May, 1968, she had met Gainsbourg, a famous singer-songwriter and an established playboy, on the set of the romantic comedy “Slogan.” He was recovering from a breakup with Brigitte Bardot, Birkin was recovering from the breakup of her marriage, and all of France was about to be thrown into the heady days of a student uprising, when huge labor strikes brought the country to a standstill. Neither Gainsbourg nor Birkin was impressed. “He was Russian!” Birkin told Le Monde, in 2013. “It seemed anecdotal compared to the October Revolution.”

The Birkin of the Gainsbourg years is the one we know best, the It Girl of Meltzer’s title. According to Elinor Glyn, who popularized the concept in her 1927 novel, “It,” the quality couldn’t be reduced to mere sex appeal. “The most exact description,” she told an interviewer, is “some curious magnetism, and it always comes with people who are perfectly, perfectly self-confident . . . indifferent to everything and everybody.” In the blockbuster silent film “It,” based on Glyn’s novel, Clara Bow plays Betty Lou Spence, a spirited shopgirl who attracts the attention of her wealthy boss when she’s seen on the town in a chic flapper look reworked from a shabby day dress. Slicing off her sailor collar to create a deep-V neckline and attaching some fake flowers to her hip, Betty Lou marches out her tenement apartment and into a fancy restaurant with her head high, pointedly unbothered by the looks she gets from upper-crust diners.

Birkin projected just this sort of youthful insouciance. Skinny and flat-chested, with big teeth and a galumphing walk, she was no pinup and knew it. She styled herself, Meltzer notes, “in contrast to the quintessential French women of the time”: instead of hip-hugging dresses and high heels, there were Repetto flats, denim cutoffs, soft knits, and crocheted crop tops. The look was improvisational yet elegant, a perfect match for shifting social and sartorial trends. If a young Parisienne in the nineteen-twenties could feel liberated by the loose tailoring and comfortable fabrics of Coco Chanel’s new suits, Birkin’s generation wanted something even less restrictive. “I don’t care much about expensive couture clothes,” Birkin told Women’s Wear Daily, in 1969. “I like the floppy look of Saint Laurent.”

And yet Birkin was far from the self-reliant gamine embodied by Clara Bow. According to Meltzer, Birkin seemed unable “to cultivate much sense of self outside of her relationships with men and her children.” At first, life with Gainsbourg was idyllic. Shacked up on the Rue de Verneuil with Kate and another baby, Charlotte, on the way, they became a bohemian power couple. They took Kate, dressed in Baby Dior, to casinos and bought a house in Normandy, where they went boating with the children. Being Birkin’s partner was an ego boost for Gainsbourg, who had never been conventionally handsome and whose heavy drinking and smoking had aged him prematurely. (He had his first heart attack at forty-five and would die of another, at sixty-two.) “When they tell me I’m ugly,” he crows on his song “Des Laids des Laids,” from 1979, “I laugh softly, so as not to wake you up.”

Gainsbourg doted on Birkin and their girls, but he also went through periods of being, in Birkin’s words, “systematically drunk”—and, at times, violent. “I was too abusive,” Meltzer quotes him saying. “I came home completely pissed, I beat her. When she gave me an earful, I didn’t like it: two seconds too much and bam!” Birkin’s diaries suggest a man who was insecure, moody, and controlling:

Everything revolves around him, his films, his records, his life, the rest mustn’t change, neither the children nor me, orders at table, hard words, and unfair on Kate, this masculine superiority that dominates everything, that arranges everything, the house must be just so and no other way, the children are growing but they mustn’t change. He’s like that. And if there’s a revolt, I’m the one who’s sick or changed, or good for nothing.

“When I’m depressed,” she admitted, “I sometimes want to die very much and by his hand. Why not? I’m so tired of the complication of living.”

In 1979, Birkin began an affair with the filmmaker Jacques Doillon, who was thirty-five to her thirty-two—an invigorating change from Gainsbourg, eighteen years her senior. The new relationship promised something less complicated, more harmonious. “I want a house full of sunlight,” she wrote, “nothing forbidden, no more orders.” She took Kate and Charlotte to a hotel, leaving Gainsbourg behind but not yet formalizing things with Doillon. The two men were “like complementary bookstands,” she wrote. “Let go one and you slide, let go both and you fall. . . . So there I am, stubbornly living my life as best I can without either.” This period of independence was short-lived. Soon, she and Doillon moved in together, and in 1982 their daughter, Lou, was born. Gainsbourg sent her a gift basket full of baby clothes, from “Papa Deux.”

It was around this time that Birkin made her most celebrated contribution to fashion. On an Air France flight, she found herself seated next to Jean-Louis Dumas, the chief executive of Hermès. As Birkin struggled to stow her signature wicker basket, spilling its contents, Dumas suggested that she needed a new bag. This prompted Birkin to complain that she couldn’t find one that both looked good and held all her stuff. She recalled sketching a roomy, wedgelike design on the back of an air-sickness bag. Dumas took the design to his studio, tweaked it, and the Birkin was born. Current models can sell for more than four hundred thousand dollars; in July, at Sotheby’s, the prototype went for ten million. It was the second most valuable fashion item ever sold at auction, behind only Dorothy’s slippers.

The arrival of the Birkin bag marked the beginning of a more creatively fulfilling period for its namesake. She continued to work in film, earning César nominations for Best Actress for her work in Doillon’s “La Pirate” (1984) and Best Supporting Actress in “La Belle Noiseuse” (1991), Jacques Rivette’s drama about a painter who becomes infatuated with a younger woman, to the chagrin of his wife and former muse, played by Birkin. Her most significant achievement, however, was a series of concerts, in 1987, at the Bataclan, the Paris theatre that would become the site of a terrorist attack, in 2015. For Birkin, the performances represented a passage between her gangly, passive youth and a more confident middle age, a transition she announced, characteristically, through her style. “I cut my hair off like a boy, I wore men’s clothes,” she said later. “I only wanted people to hear the music and the words. It was fantastic.”

For Birkin, getting older meant a kind of invisibility, a prospect that at once unnerved and elated her. At a Lincoln Center screening of “Jane B. par Agnès V.,” in 2016, she explained—in that same girlish voice—that she had agreed to do the film because she’d felt that, on the eve of turning forty, she could now be convincing as “any old person,” no longer defined by her famous face. It’s an extraordinary remark. For one thing, the whole purpose of the movie is to offer a portrait of Birkin as her specific, unprecedented self. More to the point, the Jane Birkin who appears before Varda’s camera is inimitably stunning, and the one who sat on the stage at Lincoln Center—nearly seventy years old, in a gray frock coat, hair unbrushed, spectacles perched on the edge of her nose—was just as magnetic, with a gravity and a self-possession that have only enhanced her charm.

Meltzer is not quite sure how to handle this phase of Birkin’s life. On the one hand, she paints her as a Nancy Meyers-ish heroine, channelling Diane Keaton in slacks and blazers, “ready to focus back on her own self as she ages.” There is a sentence that describes Birkin’s choice to forgo plastic surgery as “an almost anti-capitalist way of rebelling against gender norms.” On the other hand, she seems to consider Birkin’s aging as a process of subtraction. But, if the elder Birkin became “less classically pretty,” she also lived long enough to prove that her beauty was something enduring, even primordial.

For evidence, see Charlotte Gainsbourg’s 2021 documentary, “Jane by Charlotte,” a sequel of sorts to Varda’s film. Critics were mixed on it, with the Times calling it “defiantly insular.” Meltzer writes, “Charlotte said the theme of the film was a daughter looking for her mother, which is accurate but doesn’t mean it was an artistic success.” In reality, “Jane by Charlotte” is a cinematic essay on beauty, as Gainsbourg uses her camera to stroke, squeeze, and caress Birkin’s body, lingering on her gnarled hands, the play of light over her cheekbones, her feet in Converse sneakers.

Gainsbourg shoots her mother as if she were a medieval sculpture of a sad but radiant saint whom the passage of time only ennobles. She shoots her, in other words, as a human being who has something most human beings do not—an accent of grace. Singing onstage at New York’s Beacon Theatre or puttering around her house in Brittany, Birkin appears shorter and stouter, with thin lips and sunspots. She moves slowly, in recovery from treatment for leukemia and from an immense trauma—the death, perhaps by suicide, of her daughter Kate, in 2013. When you look at her, you experience a sense not of loss but of revelation. She is a person of substance, of mettle hard-earned. This is how lovely she always was, or, rather, was always going to be. ♦

Published in the print edition of the September 22, 2025, issue, with the headline “Saving Face.”

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 24

- Views

- 16K

D

- Replies

- 230

- Views

- 122K

- Replies

- 33

- Views

- 6K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)