-

Share with us... Your Best & Worst Collections of F/W 2026.27

-

Xenforo Cloud is upgrading us to version 2.3.10 on Wednesday Apr 01, 2026 at 12:00 AM PST. Expect a temporary downtime during this process. More info here

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Andy Warhol & The Factory

- Thread starter Whitelinen

- Start date

Has anyone seen Poor Little Rich Girl? I wonder if it is out on DVD...I read the first half of the film is out of focus?

I have seen it, and that´s correct. The first half is out of focus, but the rest is great!

I bought a copy on ebay.

^Thanks- I managed to piece together the whole film from YouTube!  Probably a hopeless thing, but I wonder if there is a transcription of Edie's dialogue in "Poor Little Rich Girl"...I would love to know what she is saying but a lot of the background music makes it difficult to hear...

Probably a hopeless thing, but I wonder if there is a transcription of Edie's dialogue in "Poor Little Rich Girl"...I would love to know what she is saying but a lot of the background music makes it difficult to hear...

Probably a hopeless thing, but I wonder if there is a transcription of Edie's dialogue in "Poor Little Rich Girl"...I would love to know what she is saying but a lot of the background music makes it difficult to hear...

Probably a hopeless thing, but I wonder if there is a transcription of Edie's dialogue in "Poor Little Rich Girl"...I would love to know what she is saying but a lot of the background music makes it difficult to hear...

Camille Pegram

Member

- Joined

- Jul 3, 2012

- Messages

- 43

- Reaction score

- 0

Has anyone seen Poor Little Rich Girl? I wonder if it is out on DVD...I read the first half of the film is out of focus?

Check youtube, I know someone had posted it ther a few yrs back.

- Joined

- Jul 24, 2010

- Messages

- 105,287

- Reaction score

- 68,978

NY Art Beat March 20, 2012

Inspired Identities and the Imagination of Jane Forth

Photo Veronica Ibarra

Stylist Rachel Gilman

Model Jane Forth

Hair Saya Hughes

Makeup Kabuki

Visitors to the Museum of Modern Art’s Cindy Sherman retrospective may naturally expect visually rich yet perhaps unusual photographs. But they will not be prepared for the absolutely jarring quality of Sherman’s experimentation with the complex multiplicity of identities that a female may inhabit. Images of the somber or anxious woman give way to thoroughly twisted distortions of gender and tragic images of fury and failure. Among the most wonderful is the wrathful woman with platinum blonde hair, clad in black, one bloodshot eye peering through her disheveled hair. The photographs produced by Sherman’s imagination are steeped in mystery, appearing to have been captured in the aftermath of some devastating scenario like a sad separation or some undesired encounter.

The critic Howard Halle compares some of Sherman’s work to Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series (although I cannot imagine to what her nightmarish clown series might be compared). On the faces of the women she is portraying, make-up is expertly used to almost violent effect: to puff up the lips to garish proportions or to convey an intense worry or gripping melancholy. Maybe the art world should not have been as surprised as it was when images created by Sherman were seen all over the city as advertisements for MAC Cosmetics. As part of her larger creative project, the painted faces of Sherman’s characters represent the ambition, and perhaps the folly, of everyday attempts to preserve youth, to represent wealth, or to celebrate one’s own beauty. Her work is so profound precisely because it wrestles with individuals’ inspired efforts to renew their images, to aspire to new identities, and to bend and twist the commonplace into something far greater.

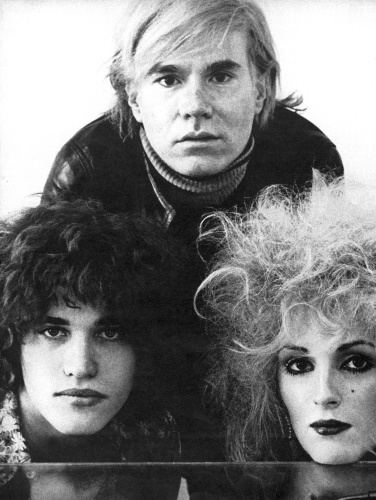

Alongside Sherman, few women have stood at the intersection of the realms of make-up, art, and film like Jane Forth, a Warhol Superstar whose use of make-up yielded iconic looks that were thoroughly hers, elegant yet subdued. In contrast to so many who attempted to recycle images of faded Hollywood glamour queens, Forth created a unique identity that was also authentically her, the result of experimentation and a stunning visual sense, not dissimilar to Sherman’s. The creation of this visual identity occurred, of course, within the equally unique context of the Warhol Factory. After a time as one of Warhol’s most dazzling Superstars, however, Forth removed herself from the spotlight, leaving many to wonder what became of her. After observing the attention given to the deployment of make-up in artistic compositions and the questions of feminine beauty triggered by Sherman’s work, I decided to find Forth. Having grown up in Michigan before moving to the East Coast, Forth is now a mother of grown children and lives in Hudson, New York. She recently visited Manhattan for an interview.

Forth is best known for appearing in Paul Morrissey’s Trash (1970) and the lesser known but still brilliant L’Amour (1973). In the latter of these, Warhol and Morrissey took several Factory fixtures to Paris for a film in which the allure of make-up, fantasy, and mass culture runs throughout. Raggedy hippies played by Forth and Donna Jordan arrive in Paris ready to be transformed by Patti D’Arbanville and friends like Corey Tippin and Karl Lagerfeld (who at that time sported wavy black hair). Glamorous identities gradually emerge via new make-up and hair styles. Although set in Paris, the film is thoroughly Pop: Forth and Jordan rehearse for a musical wearing Pepsi Cola shirts and fruit hats, Jordan pines for hamburgers throughout the film, and Forth’s character extols the virtues of American TV, particularly the Mickey Mouse show. In what is Forth’s most memorable scene, a local waif named Max attempts a seduction. Massaging a finely chiseled statue, the heavily accented Parisian asks, “You don’t like the sex of a man?” In her classic tone, Forth’s character says, “It’s ok, I mean. But you know, I’d rather buy make-up. I get more excited by make-up.”

Recalling the inspiration behind her own famous use of make-up, today Forth remembers being pulled toward older movies, particularly black-and-white films “due to their contrast,” she says. Forth’s favorites included Clara Bow, Claudette Colbert, Bette Davis, Hedy Lamarr, Dorothy Lamour, Vivian Leigh, and Myrna Loy. To develop her own style, she says, “I experimented with many different looks as a young adolescent. I was not consciously looking to create something new as an image. I took my inspirations one step further and mixed it with my own creativity and artistic eye and my look appeared. It felt right and it felt very comfortable to me when I finally found it.” When I asked how she accounted for the ability of make-up to inspire and provoke, as in the glamorous portraits of movie starlets or Sherman’s depictions of broken identities, Forth replies, “When someone paints their face, you’re creating something. You’re stimulating your own imagination.”

Screening Forth’s scene in Morrissey’s Trash tends to leave viewers agape. The lead character, a drug addict played by Warhol Superstar Joe Dallesandro, breaks into an apartment only to be discovered by a brazen young newlywed from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, named Jane. The scene is one of what Forth calls “a series of what we would term as trashy events” in the film. The famous scene with Forth, Dallesandro, and Bruce Pecheur, who plays Forth’s husband, has been noted for its explicit and at times humorous exploration of sexuality, marital relationships, drug use, class divisions, and contemporary standards of beauty. Forth’s decision to participate in the film was a bit more prosaic. She was pulled toward the filmmaking community by certain social ties, she says, and with particular regard to the film, Forth says simply, “I needed to earn money to buy Christmas gifts that year, so I took the job.”

Incredibly, the teenage Forth and her co-stars spun out dialogue that is at once captivating and hilarious with little direction. Forth explains, “Paul, who was very nice, had a very rough story line: ‘Joe’s a junkie thief and you are a rich girl home alone. Take it from there.’ We were ad-libbing and creating the dialogue as we went along. I did my own hair and make-up and supplied my own clothing.” Her scene with Dallesandro is one of escalation, ending with Jane in a fit of hysteria and Joe being perilously close to death. I wondered if that kind of crescendo was intended by the actors or Morrissey. Forth replies, “That wasn’t expected. That just happened. We’d take off on each other. It was a joint effort. It’s really ad-libbing.” Forth also recalls her off-screen relationship with Dallesandro as being very friendly. As she remembers, “Joe and I had a really easy-going relationship as friends,” and even recalls holding play dates with their children and cooking dinner together.

Some viewers are sympathetic to the humor and wit of Forth’s exchange with Dallesandro and Pecheur. Others are appalled. Most are inevitably startled by her sudden appearance, mysterious demeanor, alabaster skin, and the rosy cheeks echoed by her round red plastic earrings. Illustrator Joshua David McKenney, who recently drew Forth, considers her a muse and a strong influence on his artistic practice. When he first saw her appear opposite Dallesandro, he says, “I was instantly enamored by her. I thought she was so beautiful and loved that she was so simply styled and graphic looking. I also loved the way she spoke and I watched the scene with her and Joe over and over. Her beauty was like nothing I’d ever seen. Now that I’m an adult she has this special place in my mind as the best example of my favorite kind of way a girl can be beautiful.” Jon Davies, author of Trash: A Queer Cinema Classic observes, Forth “strikes an indelible figure with her petite eyebrows, porcelain visage, impossibly haughty drawl, and quick-to-cruelty demeanor.” After being recruited by Morrissey as a last minute replacement, did the teenage Forth develop this celebrated visage specifically for the film? No, Forth tells me, “That’s how I looked every day.”

Of course, individuals whose everyday appearance grabbed attention in the way that Forth’s did were exactly the kind of people that Warhol pulled toward him and are still the kind of individuals inspired by the identities of his Factory Superstars. This past February marked the 25th anniversary of Warhol’s death. He continues to cast a long shadow over the art world, especially here in New York. His silver statue in Union Square was very popular, new books continue to be written about him, and his influence on so many cultural producers is apparent. Forth ties Warhol’s enduring allure to his personality. She says, “There was always a mysterious air to Andy’s personality. It seemed to stimulate the need in people to want to find out more about him, or try to get close to him, or get his attention. His mystery was not contrived. It was just him.”

Forth traveled with Warhol, attended events with him, and worked as a receptionist at the Factory alongside Dallesandro. Yet her recollections are marked by more private moments. Forth recalls, “My most vivid memory of Andy was receiving phone calls in the middle of the night from him to see if I was watching the same classic movie that he was watching.” And she usually was, she remembers. Forth also recalls spending summer weekends in Southampton with Warhol, Jed Johnson, Peter Brant, and Fred Hughes. On Sunday mornings, Warhol would sit under a giant tree and read the newspaper. Hughes would play Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and the group would at times venture into town to buy rhubarb pies, lobster salad, and fresh berries. She adds, “I would always buy my Yoo-hoos. I loved Yoo-hoo. […] It would be so quiet, relaxed, beautiful, so normal and peaceful and tranquil.”

Given this unique spot among the Factory Superstars and within a scene that continues to define the imagination of the New York art world, why did she depart? For years, Forth’s absence from the world of cultural production produced its own lingering mystery. In his recently re-released biography of Dallesandro, Michael Ferguson cites Morrissey as saying that she lost interest in film because she became “self conscious.” When asked if she agreed with this claim, Forth replies, “I did find myself becoming self conscious due to the lack of desire to be an actress, but in exchange I recognized and discovered that I loved working behind the camera in make-up and special effects.” She therefore moved from standing in front of the flashing lights to moving behind the scenes. Her work as a union-certified make-up artist for films, TV commercials, music videos, and even PBS after school movies included work with Bob Giraldi, Pat Benatar, Barry Manilow, and Julio Iglesias. For a time she was also married to Oliver Wood, cinematographer for films like Sister Act 2, the Bourne trilogy, and Fantastic Four.

Through the unique looks and characters she crafted, Forth continues to have an effect on cultural production today, inspiring fashion designers like Anna Sui and make-up artists like Kabuki, who now regularly paints the faces of contemporary icons of music and film. I asked Forth how she might account for make-up’s enduring and even enigmatic allure, for its ability to both create and cut through ambiguity. Why does make-up as its own artistic practice continue to play so prominently in the work of creators like Sherman, Sui, and others? Forth responds, “Make-up stimulates the imagination, imagination is the catalyst for creativity, and creativity is the source of inspiration, and the allure is the visual stimuli.” Having themselves been forcefully inspired to create new and powerful identities, Forth and artists like Sherman have bequeathed a whole set of painted faces to ignite the imaginations of future everyday icons.

nyartbeat.com

Inspired Identities and the Imagination of Jane Forth

Photo Veronica Ibarra

Stylist Rachel Gilman

Model Jane Forth

Hair Saya Hughes

Makeup Kabuki

Visitors to the Museum of Modern Art’s Cindy Sherman retrospective may naturally expect visually rich yet perhaps unusual photographs. But they will not be prepared for the absolutely jarring quality of Sherman’s experimentation with the complex multiplicity of identities that a female may inhabit. Images of the somber or anxious woman give way to thoroughly twisted distortions of gender and tragic images of fury and failure. Among the most wonderful is the wrathful woman with platinum blonde hair, clad in black, one bloodshot eye peering through her disheveled hair. The photographs produced by Sherman’s imagination are steeped in mystery, appearing to have been captured in the aftermath of some devastating scenario like a sad separation or some undesired encounter.

The critic Howard Halle compares some of Sherman’s work to Andy Warhol’s “Death and Disaster” series (although I cannot imagine to what her nightmarish clown series might be compared). On the faces of the women she is portraying, make-up is expertly used to almost violent effect: to puff up the lips to garish proportions or to convey an intense worry or gripping melancholy. Maybe the art world should not have been as surprised as it was when images created by Sherman were seen all over the city as advertisements for MAC Cosmetics. As part of her larger creative project, the painted faces of Sherman’s characters represent the ambition, and perhaps the folly, of everyday attempts to preserve youth, to represent wealth, or to celebrate one’s own beauty. Her work is so profound precisely because it wrestles with individuals’ inspired efforts to renew their images, to aspire to new identities, and to bend and twist the commonplace into something far greater.

Alongside Sherman, few women have stood at the intersection of the realms of make-up, art, and film like Jane Forth, a Warhol Superstar whose use of make-up yielded iconic looks that were thoroughly hers, elegant yet subdued. In contrast to so many who attempted to recycle images of faded Hollywood glamour queens, Forth created a unique identity that was also authentically her, the result of experimentation and a stunning visual sense, not dissimilar to Sherman’s. The creation of this visual identity occurred, of course, within the equally unique context of the Warhol Factory. After a time as one of Warhol’s most dazzling Superstars, however, Forth removed herself from the spotlight, leaving many to wonder what became of her. After observing the attention given to the deployment of make-up in artistic compositions and the questions of feminine beauty triggered by Sherman’s work, I decided to find Forth. Having grown up in Michigan before moving to the East Coast, Forth is now a mother of grown children and lives in Hudson, New York. She recently visited Manhattan for an interview.

Forth is best known for appearing in Paul Morrissey’s Trash (1970) and the lesser known but still brilliant L’Amour (1973). In the latter of these, Warhol and Morrissey took several Factory fixtures to Paris for a film in which the allure of make-up, fantasy, and mass culture runs throughout. Raggedy hippies played by Forth and Donna Jordan arrive in Paris ready to be transformed by Patti D’Arbanville and friends like Corey Tippin and Karl Lagerfeld (who at that time sported wavy black hair). Glamorous identities gradually emerge via new make-up and hair styles. Although set in Paris, the film is thoroughly Pop: Forth and Jordan rehearse for a musical wearing Pepsi Cola shirts and fruit hats, Jordan pines for hamburgers throughout the film, and Forth’s character extols the virtues of American TV, particularly the Mickey Mouse show. In what is Forth’s most memorable scene, a local waif named Max attempts a seduction. Massaging a finely chiseled statue, the heavily accented Parisian asks, “You don’t like the sex of a man?” In her classic tone, Forth’s character says, “It’s ok, I mean. But you know, I’d rather buy make-up. I get more excited by make-up.”

Recalling the inspiration behind her own famous use of make-up, today Forth remembers being pulled toward older movies, particularly black-and-white films “due to their contrast,” she says. Forth’s favorites included Clara Bow, Claudette Colbert, Bette Davis, Hedy Lamarr, Dorothy Lamour, Vivian Leigh, and Myrna Loy. To develop her own style, she says, “I experimented with many different looks as a young adolescent. I was not consciously looking to create something new as an image. I took my inspirations one step further and mixed it with my own creativity and artistic eye and my look appeared. It felt right and it felt very comfortable to me when I finally found it.” When I asked how she accounted for the ability of make-up to inspire and provoke, as in the glamorous portraits of movie starlets or Sherman’s depictions of broken identities, Forth replies, “When someone paints their face, you’re creating something. You’re stimulating your own imagination.”

Screening Forth’s scene in Morrissey’s Trash tends to leave viewers agape. The lead character, a drug addict played by Warhol Superstar Joe Dallesandro, breaks into an apartment only to be discovered by a brazen young newlywed from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, named Jane. The scene is one of what Forth calls “a series of what we would term as trashy events” in the film. The famous scene with Forth, Dallesandro, and Bruce Pecheur, who plays Forth’s husband, has been noted for its explicit and at times humorous exploration of sexuality, marital relationships, drug use, class divisions, and contemporary standards of beauty. Forth’s decision to participate in the film was a bit more prosaic. She was pulled toward the filmmaking community by certain social ties, she says, and with particular regard to the film, Forth says simply, “I needed to earn money to buy Christmas gifts that year, so I took the job.”

Incredibly, the teenage Forth and her co-stars spun out dialogue that is at once captivating and hilarious with little direction. Forth explains, “Paul, who was very nice, had a very rough story line: ‘Joe’s a junkie thief and you are a rich girl home alone. Take it from there.’ We were ad-libbing and creating the dialogue as we went along. I did my own hair and make-up and supplied my own clothing.” Her scene with Dallesandro is one of escalation, ending with Jane in a fit of hysteria and Joe being perilously close to death. I wondered if that kind of crescendo was intended by the actors or Morrissey. Forth replies, “That wasn’t expected. That just happened. We’d take off on each other. It was a joint effort. It’s really ad-libbing.” Forth also recalls her off-screen relationship with Dallesandro as being very friendly. As she remembers, “Joe and I had a really easy-going relationship as friends,” and even recalls holding play dates with their children and cooking dinner together.

Some viewers are sympathetic to the humor and wit of Forth’s exchange with Dallesandro and Pecheur. Others are appalled. Most are inevitably startled by her sudden appearance, mysterious demeanor, alabaster skin, and the rosy cheeks echoed by her round red plastic earrings. Illustrator Joshua David McKenney, who recently drew Forth, considers her a muse and a strong influence on his artistic practice. When he first saw her appear opposite Dallesandro, he says, “I was instantly enamored by her. I thought she was so beautiful and loved that she was so simply styled and graphic looking. I also loved the way she spoke and I watched the scene with her and Joe over and over. Her beauty was like nothing I’d ever seen. Now that I’m an adult she has this special place in my mind as the best example of my favorite kind of way a girl can be beautiful.” Jon Davies, author of Trash: A Queer Cinema Classic observes, Forth “strikes an indelible figure with her petite eyebrows, porcelain visage, impossibly haughty drawl, and quick-to-cruelty demeanor.” After being recruited by Morrissey as a last minute replacement, did the teenage Forth develop this celebrated visage specifically for the film? No, Forth tells me, “That’s how I looked every day.”

Of course, individuals whose everyday appearance grabbed attention in the way that Forth’s did were exactly the kind of people that Warhol pulled toward him and are still the kind of individuals inspired by the identities of his Factory Superstars. This past February marked the 25th anniversary of Warhol’s death. He continues to cast a long shadow over the art world, especially here in New York. His silver statue in Union Square was very popular, new books continue to be written about him, and his influence on so many cultural producers is apparent. Forth ties Warhol’s enduring allure to his personality. She says, “There was always a mysterious air to Andy’s personality. It seemed to stimulate the need in people to want to find out more about him, or try to get close to him, or get his attention. His mystery was not contrived. It was just him.”

Forth traveled with Warhol, attended events with him, and worked as a receptionist at the Factory alongside Dallesandro. Yet her recollections are marked by more private moments. Forth recalls, “My most vivid memory of Andy was receiving phone calls in the middle of the night from him to see if I was watching the same classic movie that he was watching.” And she usually was, she remembers. Forth also recalls spending summer weekends in Southampton with Warhol, Jed Johnson, Peter Brant, and Fred Hughes. On Sunday mornings, Warhol would sit under a giant tree and read the newspaper. Hughes would play Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and the group would at times venture into town to buy rhubarb pies, lobster salad, and fresh berries. She adds, “I would always buy my Yoo-hoos. I loved Yoo-hoo. […] It would be so quiet, relaxed, beautiful, so normal and peaceful and tranquil.”

Given this unique spot among the Factory Superstars and within a scene that continues to define the imagination of the New York art world, why did she depart? For years, Forth’s absence from the world of cultural production produced its own lingering mystery. In his recently re-released biography of Dallesandro, Michael Ferguson cites Morrissey as saying that she lost interest in film because she became “self conscious.” When asked if she agreed with this claim, Forth replies, “I did find myself becoming self conscious due to the lack of desire to be an actress, but in exchange I recognized and discovered that I loved working behind the camera in make-up and special effects.” She therefore moved from standing in front of the flashing lights to moving behind the scenes. Her work as a union-certified make-up artist for films, TV commercials, music videos, and even PBS after school movies included work with Bob Giraldi, Pat Benatar, Barry Manilow, and Julio Iglesias. For a time she was also married to Oliver Wood, cinematographer for films like Sister Act 2, the Bourne trilogy, and Fantastic Four.

Through the unique looks and characters she crafted, Forth continues to have an effect on cultural production today, inspiring fashion designers like Anna Sui and make-up artists like Kabuki, who now regularly paints the faces of contemporary icons of music and film. I asked Forth how she might account for make-up’s enduring and even enigmatic allure, for its ability to both create and cut through ambiguity. Why does make-up as its own artistic practice continue to play so prominently in the work of creators like Sherman, Sui, and others? Forth responds, “Make-up stimulates the imagination, imagination is the catalyst for creativity, and creativity is the source of inspiration, and the allure is the visual stimuli.” Having themselves been forcefully inspired to create new and powerful identities, Forth and artists like Sherman have bequeathed a whole set of painted faces to ignite the imaginations of future everyday icons.

nyartbeat.com

rebel

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 7, 2013

- Messages

- 1,245

- Reaction score

- 199

Andy Warhol's Screen Tests

risdmuseum“Seeing 20 of the Screen Tests in a row makes you realize just how carefully crafted they really were, as visual experiences.”

— Blake Gopnik, The Daily Beast “Daily Pic”

Andy Warhol’s filmmaking process was inspired not only by his fascination with people, but by his desire to capture the actual experience of life. As he noted in his book POPism: The Warhol ’60s, “What I liked was chunks of time all together, every real moment… I only wanted to find great people and let them be themselves.”

Between 1964 and 1966, Warhol created more than 350 Screen Tests, 20 of which are screened in this exhibition. Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Nico, Lou Reed, and Susan Sontag were among the hundreds of subjects, all posed and recorded on 100-foot rolls of silent, black & white film by Warhol’s stationary 16mm Bolex camera. These portraits are projected in slow motion so that each lasts about four minutes; as a sequence, they induce an almost hypnotic reverie that “help the audiences get more acquainted with themselves,” as Warhol once said.

This exhibition is organized by The Andy Warhol Museum, one of the four Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh.

“Although he’s best known for his iconic paintings of soup cans and celebrities, Pop artist Andy Warhol was also an avid photographer and filmmaker. Over the next few months, the RISD Museum will explore this side of Warhol’s art in two related exhibits, both of which focus on the artist’s work behind the camera.”

— Providence Journal Q&A with RISD Museum director John W. Smith

Related exhibition: Andy Warhol’s Photographs opens January 31, 2014.

thedailybeastAnother Warhol “Screen Test”, this time shot in early 1965, and putting a static Edie Sedgwick on screen for four minutes. (This week’s Pics will be entirely devoted to the “Tests”, since I recently got to see 20 in one go, at the RISD museum.)

The “Screen Tests” are much more varied than even their fans recognize, but this is the classic version, starring the classic Factory Superstar: The camera never moves or zooms or changes focus, and the sitter seems to be trying to look impassively into the lens. (YouTube has a bunch of lousy copies of the film.) This piece comes across at first as a standard fashion-world cover shot, as we’d expect from a former commercial artist like Warhol. Sedgwick seems to have been chosen, like a model, for her charisma and presence on camera, and the aim could be to document this, using a flattering on-camera light. But, as usual with Warhol, what starts off seeming straightforward soon reveals itself as weird: Though we are all used to presenting ourselves for the instant snap of a camera – or even for the frozen moment in an oil painting – we have no idea what it means to present ourselves over time, as unmoving human beings, and Sedgwick doesn’t, either. We viewers can feel the strain as Sedgwick tries to figure out what to do and how to be, and we feel for her, too. We might just stare into a lover’s eyes for this long, but probably not – and Sedgwick of course has nothing to stare at other than the cyclopean, unblinking, unfeeling, pupil-less eye of Warhol’s camera, and by implication at our absent eyes as we watch the footage. She seems pinned down like a bug, not just unmoving but frozen, or helpless, or under some Svengali’s control. (Why else, in the normal course of things, would anyone sit so still? The shadow lurking at left seems almost vampiric.) Thanks to the artifice of Andy’s steady gaze, Edie seems as vulnerable as she’s always been made out to have been in real life.

But the stress in this piece, or in any “Screen Test”, isn’t only on the sitter; we watchers are also stressed out by the task Warhol sets us. Before the “Screen Tests”, I wonder if any movie had ever asked an audience to suffer such an uninterrupted, stationary view of any star or subject? Four minutes is simply a very long time to stare at any image: Even the greatest Cezanne rarely gets that kind of unwavering attention. But that’s the kind of attention that Warhol’s “Screen Tests” demand of us. Since “nothing” happens in them – since there’s no larger plot or configuration to cling to – we can’t afford to look away, for fear of missing some telling detail. (Cezanne is full of details, too, of course, but we know that they will endure a lapse in our attention.) When every detail gets equal weighting, that is, none can be safely skipped. Trying to take notes on these pieces is murder, since you can’t afford to look down as you write. Warhol, supposedly a master of the superficial, as usual gives us works that demand the most profound thought and attention.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 24

- Views

- 16K

D

- Replies

- 37

- Views

- 8K

- Replies

- 6K

- Views

- 2M

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 1 (members: 0, guests: 1)

Kind of sad, though- she was so much in her own world...

Kind of sad, though- she was so much in her own world...