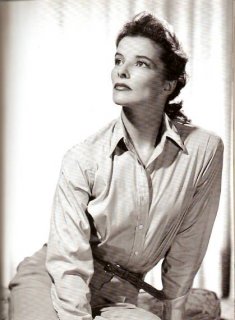

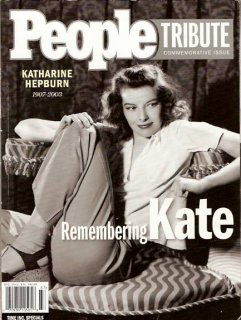

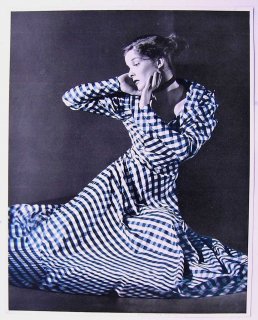

The Theatrical Katharine Hepburn, in Journals and Letters

The letter to George C. Tyler, a theatrical producer in New York, suggests a young actress that he “might keep in mind” for a part. “She has had a variety of experience,” it says, and “she comes from a good family.”

The well-bred lady was

Katharine Hepburn, and the undated letter, from a family friend, is part of a cache of theater-related photographs, scrapbooks, journals, scripts and more. Four years after Hepburn’s death, the material forms a gift from her estate to the

New York Public Library that is to be announced today. The documents, all related to Hepburn’s stage career, offer a revealing glance at her personality, profession and obsessions.

There are fan notes from

Henry Fonda,

Laurence Olivier and

Judy Garland. “I’ve always said you were our leading actress,” Garland wrote during the 1952 run of “The Millionairess,” before complaining, “I am getting fat and pregnant and mean.” After seeing “The West Side Waltz” in 1981,

Charlton Heston wrote, “You have made all our hearts tremble, one time or another.”

Yet as her niece

Katharine Houghton explained, Hepburn’s “relationship with the theater was really very problematic.”

She was fired from her first role, in “The Big Pond” in 1928, after one performance.

Dorothy Parker memorably wrote in her review of “The Lake” in 1933 that “Miss Hepburn runs the gamut of emotions from A to B.”

The trouble was her voice, which

Tallulah Bankhead once likened to “nickels dropping in a slot machine.” Hepburn was unable to control it and often lost the ability to speak during performances, Ms. Houghton said.

It made the theater a terrifying place. “‘The Lake’ was such a horrible experience for her,” Ms. Houghton said, “She was sure that the audience was her enemy.”

“She was basically a very, very shy person,” Ms. Houghton continued, “terrified of coming into a room even at family get-togethers.”

In a journal from a 1950-51 road tour of “As You Like It,” Hepburn wrote that she kept her fears of a cold and laryngitis to herself: “I find that people are always ready to bury you and that the only thing that keeps you out of your grave is your own determination to stay out.”

After losing her voice during the run of

George Bernard Shaw’s “Millionairess,” she went to a speech coach, Alfred Dixon. Her detailed notes are in the collection, inside a leather-bound folder with the gold-embossed initials “S.T.”

“We’re assuming it belonged to

Spencer Tracy,” the great love of her life, Bob Taylor, the collection’s curator, said. (He said the collection should be available to the public in February at the Library for the Performing Arts at

Lincoln Center.)

Not until the outpouring of acclaim for her portrayal of Coco Chanel in the 1969 musical “Coco” did Hepburn, then 62, begin to enjoy performing live, Ms. Houghton said.

Among the finds in the collection is the handwritten text of a short speech that Hepburn gave at the end of a performance of “Coco” on May 8, 1970, at the request of the actor

Keir Dullea, who wanted to commemorate the four students shot earlier that week at

Kent State University by National Guardsmen.

“Now, you may call them rebels or rabble rousers or anything you please,” Hepburn wrote. “Nevertheless, they were our kids and our responsibility. Our generation are responsible, and we must take time to pause and reflect and do something.” After asking for a moment of silence, she added, “If any of you wish to leave, you are free to do so, for if you do, I know you will still think about it.”

The speech was a surprise, Ms. Houghton said. Hepburn was “very careful not to mix politics with the theater,” she said, adding that her aunt often quoted Tracy’s comment that “actors who got involved in politics can suffer the fate of the man who shot Lincoln.”

In her journal from the “As You Like It” tour, Hepburn meticulously recorded the daily expenses for advertising, the box office receipts, theater descriptions (from the electrical current, “A.C. 110-220,” to which tap had scalding water, “the center”); hotel details (when room service quit for the night); and where to have sweaters professionally washed and blocked.

One episode she recounted was when, driving from Tulsa, Okla., to Wichita, Kan., she and her driver were arrested for speeding. Taken by the police to a lawyer’s office in Blackwell, Okla., Hepburn declared, “I have been arrested by this moron.” Hepburn’s fury grew as they were unable to find a judge. “I said that I was sorry I did not have a week to take off,” she wrote, “and if I ever found an Oklahoma car in Connecticut, I would flatten all the tires.”

She ended up singeing her coat (probably a mink, Ms. Houghton said) on a gas stove. “You must have paid $700 for it,” the lawyer commented.

Hepburn wrote, “I am ashamed to say that I was cheap enough to answer: ‘Certainly not. $5,500.’ And he just looked pathetic, and I must say I felt awfully moronic.”

As Hepburn prepared for the “As You Like It” tour, Lawrence Langner of the Theater Guild was trying to get George Bernard Shaw to sign off on a production of “The Millionairess.” He wrote Hepburn about the meeting he and his wife, Armina, had in London with Shaw, referred to as G.B.S. in his letter:

“G.B.S.: What sort of an athlete is Kate? She has to do judo. That’s what you call jiu-jitsu.

“Armina: She’s a very good athlete.

“G.B.S.: (not hearing correctly) I know she’s a good actress. I mean is she strong?

“Armina: Is she strong? Why, she gets up and plays tennis every morning. She’s one of the most athletic girls I know. She’s terrific.

“G.B.S.: Then I think it’s dangerous for her to play the part.

“L.L. (getting a word in edgeways

Why?

“G.B.S.: Dangerous for the actor she’s doing the judo with. She’ll probably kill him.

“L.L.: Oh, no, G.B.S. She’s a very tender-hearted girl. She wouldn’t kill another actor.”

)

)

Why?

Why?