Gone and Even More Collectible

By ERIC WILSON

Published: January 27, 2010

THE announcement last month that Martin Margiela had left his fashion house, following a year of considerable doubt about his presence there, suddenly changed the context of his work of the last 20 years. Rather than looking at his recent collections as representative of one of the world’s most influential designers in midcareer, the fashion world was faced with the realization that his oeuvre is now complete.

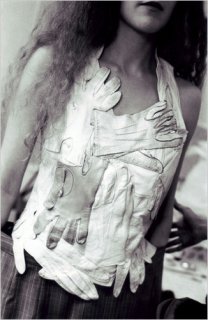

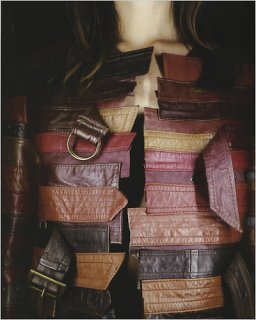

That change has resulted in a newfound nostalgia, and a collecting frenzy, for Mr. Margiela’s most unusual works — the cloven-toed “tabi” boots, for example, and his tunics fashioned of gloves, bottle caps and wigs. This is what occurred to Katy Rodriguez, a designer and owner of the vintage retailer Resurrection, when she recently obtained roughly 1,000 pieces that had been amassed by a single collector. The collection will be sold at Resurrection stores and at 1stdibs.com, an online catalog for antique and vintage retailers around the world, beginning Feb. 11.

“Enough time has gone by and enough work has been done researching Margiela’s work that we can now look at it in a historical context,” Ms. Rodriguez said. Last year, the Maison Martin Margiela published a monograph, helping to establish a timeline for the important pieces. Still, she found it helpful to put them in perspective with firsthand accounts.

While showing her own collection in Paris last year, she met Graça Fisher, now the commercial director for a Japanese label called Commuun. Ms. Fisher, as it turned out, had met Mr. Margiela when he was starting the company in Antwerp, Belgium, and she was a 19-year-old student. She was a model in eight of his shows and helped with sales, giving her a rare view inside his small circle.

“You must understand that what he was making then was really unheard of,” Ms. Fisher said in a phone interview from her home in Rome. Repurposing vintage designs, showing his clothes on non-models, refusing to talk to the press, Mr. Margiela became an enigma, often offending reporters with his provocative stance. After his first show, a Belgian newspaper published a picture of Mr. Margiela covering his face with his hand.

“His third show was on the outskirts of Paris, in a poor neighborhood,” Ms. Fisher recalled. “It was a fantastic show, but the newspaper Libération said it was scandalous.”

It’s not that Mr. Margiela never tried to fit in. There were some early interviews and appearances, but it is Ms. Fisher’s view that he found the circus not to his taste.

She described one experience when Mr. Margiela was asked by i-D magazine to be in an article about new designers. For the picture, they arrived at the Palace late one night to find the Paris nightclub in full swing. They were directed on stage, where Ms. Fisher was seated and a man behind her, at the photographer’s direction, started rubbing his hands all over her body.

“Then he said, ‘That’s it, thanks,’ ” she said.

When they left, she asked Mr. Margiela, “What was that all about?”

His reply, she said, was: “Don’t ask me. It was disgusting.”