You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Sarah Burton - Designer, Creative Director of Givenchy

- Thread starter Fatalefashion

- Start date

Miss Dalloway

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Mar 3, 2006

- Messages

- 25,698

- Reaction score

- 1,005

She has won Designer Of The Year at the BFA's (no photos?), so happy for her, great year she had, hope it goes on.

Melancholybaby

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Aug 25, 2011

- Messages

- 14,151

- Reaction score

- 2,296

Interview March 2012

Sarah Burton

Photographer: Fabien Baron

Stylist: Karl Templer

Model: not credited

Make-Up: Benjamin Puckey

Hair: Guido Palau

interviewmagazine

Article

http://www.interviewmagazine.com/fashion/sarah-burton#_

Sarah Burton

Photographer: Fabien Baron

Stylist: Karl Templer

Model: not credited

Make-Up: Benjamin Puckey

Hair: Guido Palau

interviewmagazine

Article

http://www.interviewmagazine.com/fashion/sarah-burton#_

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

Sarah Burton attends a private view for Ballgowns: British Glamour Since 1950, featuring more than sixty designs from 1950 to the present day, at The V&A on May 15, 2012 in London, England.

(May 14, 2012 - Source: Stuart Wilson/Getty Images Europe)

*Zimbio

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

Florence Welch of Florence and The Machine, designer Sarah Burton and actress Cate Blanchett attend the "Schiaparelli And Prada: Impossible Conversations" Costume Institute Gala at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on May 7, 2012 in New York City.

(May 6, 2012 - Source: Larry Busacca/Getty Images North America)

*Zimbio

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

Sarah Burton poses in the press room with the Designer of the Year Award and model Naomi Campbell during The Elle Style Awards 2012 at The Savoy Hotel on February 13, 2012 in London, England.

(February 12, 2012 - Source: Gareth Cattermole/Getty Images Europe)

*Zimbio

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

*Vogue.co.ukRoyal Blessing

SARAH BURTON will receive an OBE (Order of the British Empire) for her services to the fashion industry, as announced today in the Queen's Birthday Honour's List. The designer, who took over as creative director of Alexander McQueen in May 2010, famously created the Duchess of Cambridge's wedding dress - keeping it a secret right until the day of the ceremony itself in April last year.

Other fashion figures to be named include Mulberry creative director Emma Hill, who will receive a CBE (Commander of the British Empire), jewellery designer and VOGUE.COM blogger Lara Bohinc with a MBE (Member of the British Empire), and Vogue cover girl Kate Winslet with a CBE.

Burton first joined McQueen as an intern in 1996 and returned after her Central Saint Martins graduation. She was appointed as the label's head of womenswear in 2000 and remained McQueen's aide until his tragic death in February 2010.

Anyone can be nominated for one of the Queen's prestigious awards, although only exceptional names are honoured. Of the awards given, 41 per cent will go to women this year.

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

Chanelcouture09

Some Like It Hot

- Joined

- Feb 20, 2009

- Messages

- 10,572

- Reaction score

- 35

GivenchyHomme

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Sep 3, 2009

- Messages

- 5,481

- Reaction score

- 5,371

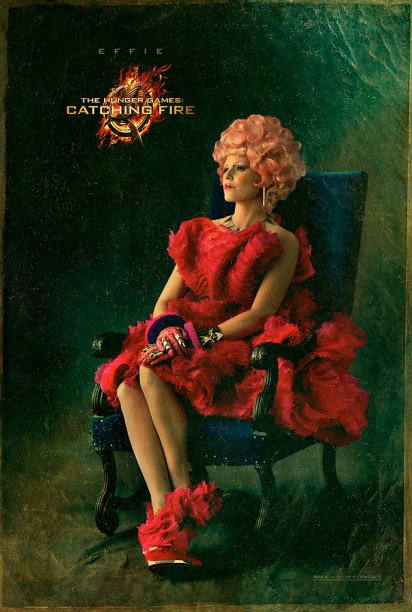

Alexander McQueen by Sarah Burton featured in The Hunger Games: Catching Fire

hypable.com, yahoo movies

hypable.com, yahoo movies

Last edited by a moderator:

nytimes.comThe Genius Next Door

By ANDREW O’HAGAN August 22, 2014 9:00 amAugust 22, 2014 9:00 am

Shy, unassuming and nice, Sarah Burton, the Alexander McQueen designer, is everything that her magically haunting collections are not.

The word “nice” overcomes a multitude of human complications: People can be rich, so long as they’re nice; they can be lazy at school or useless at work, but if they’re nice, it doesn’t matter. Nice is not the same as “great” or “lovely” or even “sweet” — it’s a category of well-pitched, ordinary decency, and a person who has niceness has everything. To my mind, Sarah Burton is not merely one of the world’s greatest designers, she just happens to be the nicest, and she is about to enjoy the flowering of her life. Once thought of as the diligent one, the silent one, the reliable power behind the dazzle of Alexander McQueen, she has emerged as a person with a devastating music of her own. Season after season, she produces beautiful combinations of the gracious and the eerie, giving us worlds that we didn’t know until we saw them. And now, after some dark winters and several seasons in the media sun, Burton seems free somehow, and ready to stake her claim on the future.

It is four years since Alexander McQueen — or “Lee,” as he was called — who in addition to being Burton’s boss was also her beloved friend and mentor, committed suicide. She was heartbroken — she finished the collection, assumed the role of head designer (which she never sought) and, soon after, in the hot glare of speculation, made the wedding dress of the decade, for the Duchess of Cambridge. To do it all, to bear it, and still be nice, is to exhibit a set of capabilities that adds even more to an already first-rate talent. I didn’t know Sarah Burton, but we got together over several weeks for this story, at her studio, at restaurants, backstage at one of her shows and, finally, at her house in North London. The first time I met her, I noticed how bitten her nails were, how self-doubting she was and how vulnerable. Yet over the weeks, her strength emerged as it does in her work: determined, sure-footed, risky, humorous and ready to open her soul in order to make contact with people. She hadn’t given an interview for almost two years before this one and even then had said very little, and she found herself speaking in a new way. A portrait emerged of a brilliant woman whose nature has been tested under severe conditions. And yet the person I met could laugh for England, making life stories, and her own life story, into an elegant aria of dreaming and believing. There is depth to her niceness, and a niceness to her depth, which has not only quadrupled her company’s fortunes, but which promises a wealth of great work to come.

Burton grew up outside Manchester. Her father was an accountant and her mother was a music teacher. She has four siblings. When she described her childhood to me she spoke a lot about education, about her father feeling that knowledge was something “nobody can take away from you.” On weekends, she and her brothers and sisters would be taken to places such as the Manchester Art Gallery, where she remembers doting on the pre-Raphaelite paintings. When we talked about influences, she sometimes glanced over her own personal things, as if she might always be haunted by the things that once haunted Lee McQueen. “I don’t have that darkness,” she said to me one morning as buses roared past her office on Clerkenwell Road. “I’m not haunted or sad. I don’t have that story in my youth.”

“But some artists are lured towards their opposite,” I said.

“That’s right. Some people think the pre-Raphaelites show a rather insipid way of representing beauty. But the painting of Ophelia [by John Everett Millais] is dark and beautiful at the same time.”

“She’s being pulled under by what Shakespeare called ‘her weedy trophies,’ ” I said. “Literally, being sunk and drowned by her dress. That’s not going to happen to you, is it?”

“No, it’s not,” she said. “Though I couldn’t always swear to it.”

“Who is your hero?” I asked.

“I think my dad is my hero,” she said. “He works so hard, and he never lies. He believes in family. He’s always been totally fair. And he treats everybody in the family equally.”

I looked for the sources of Burton’s memories of childhood, and the pictures she looked at in Manchester offer a host of beautiful, melancholy signals in abundant, colorful cloth: in “La Mort d’Arthur” by James Archer, a woman and a ghost grieve at the feet of the magical king. “The Lady of Shalott” by William Holman Hunt is drawn from Tennyson’s poem about a woman devoted to her loom and her weave who makes a fateful journey to the outside world. Yet Burton says she had a wonderfully happy childhood. The darkness was stored, and she grew up among the flora and fauna of the North — the windswept moors, the Pennine hills, the long green valleys they call the dales — which finds its way relentlessly into the best of her designs. “I’ve always loved nature,” she says. “I grew up in the countryside, and when I was a child I loved to paint and draw — that was my first love, actually. Eventually I was drawing clothes, but at first it was flowers and vegetables. So often we were outside, playing.”

“What was play for you?” I asked.

“A lot of dressing up.”

“Were you the boss?”

“Yes, always,” Burton said, laughing. “My poor younger sister, she’d get the not-so-good outfits. Fashion wasn’t something in the psyche. I learned very early on you had to go with your heart and it doesn’t matter what people say. My job is quite fearful — I don’t shout the loudest, and I’m quite shy, which was why I was reluctant to throw myself into the public eye. I love beauty, craftsmanship, storytelling and romance, and I probably don’t have the armor to survive the relentless competition that exists in this particular world. But I have my own toughness.”

You see it in her collections. There is nothing fey about them, and her bold, searching intelligence is everywhere. What she makes are couture works of art, full of a wonderful dreamlike phantasmagoria. As if the material, the organza, the silk and the leather, was alive not only to history itself but to her own personal history, the dark and the light. Sometimes her stylistic similarities to McQueen have been levied as a criticism against Burton. “What do people think I was for all those years, the cleaner?” She helped him draw out the savage brilliance that first made the house famous. For such a retiring person, Burton had no problem journeying with him into the madness of the macabre, the rigid body-contoured corsets, the gold-painted fox-skeleton wrap, the bondage pieces, the kimono-style parachute, the antlered bridal gowns. She helped give birth to these designs and is said to have kept the show on the road through many difficult episodes. But she’s ultimately a different kind of artist. It’s hard to see her sharing the dark roots of McQueen’s fetishistic damage obsession. (His famous “Highland r*pe” show, which McQueen said was about the r*pe of Scotland by England, took place before she joined the company.)

Burton’s darkness is more masked, almost more surprising. It comes unbidden from a place of relative personal optimism and sunniness. Her hauntings are more romantic, and the materials she uses are increasingly different, more celebratory of enduring life and returning nature, despite the brutality at nature’s core. I’d also argue that a larger sense of wearability, and of lightness, of small detail and cool craftsmanship, has matched the house to a new and bigger audience. She is fiercely loyal to Lee McQueen, a fact which brought her, several times during our interviews, past the brink of tears. She loves who he was and wants the company he founded to continually honor his memory, but she has to move on. The work already has moved on, and she knows that is what McQueen himself would have demanded. There is now a feeling, I detect, that she is ready to let him rest, no matter how hard that is. All the great houses had to move beyond their founding geniuses: Coco Chanel died, one must remember, and so did Cristobal Balenciaga and Yves Saint Laurent. Burton took over under traumatic circumstances, and it has taken her this long to be able to truly speak. It took a little work but eventually she opened up about some of the difficulties she’d had. We sat at a large table in her workshop with dresses hanging on every side, organza puffballs, feathered slips. She spoke with love but also with an essential determination.

....

nytimes.com“He would sit here and I would sit there,” she said, pointing to two chairs. “Sometimes he’d call me at 3 o’clock in the morning just to talk, and we had this relationship where . . . I would do anything for him. And then when he died I didn’t want the job, but then everybody was going to leave and I thought, ‘Well, what else are you going to do?’ ” When somebody with that size of talent dies you’re blessed with this legacy, and the legacy gets more and more. “Lee is Marilyn Monroe. He’s James Dean. And to be honest, it’s taken me a while to stop being afraid and see that the company needs me to be at my best.”

“Did you feel angry at him?”

“Why?”

“Because he left you. Because he destroyed himself. Because you had to finish the collection. Because you had to take over. And maybe nobody gave you permission to be angry?”

“I’m not sure,” she said. “But the hardest thing is that I never really understood the pressure he was under. He could deal with all the difficult characters just by telling them to shut up. But I’m not like that. Only now am I beginning to accept the differences between us, and it’s fine. He was a painter who worked in massive brush strokes and I’m a person with tiny brush strokes.”

The media has been on her case since that sad day in 2010. Many designers with less talent would have crumbled under the pressure, but Burton, despite all the fear and all the doubt and all the grief, has established her aesthetic. She speaks a lot off the record and doesn’t want to raise her voice, but eventually she does. “Lee and I weren’t cut from the same cloth, but we often cut into the same cloth, so it shouldn’t surprise people, after all these years, that we shared some basic creative instincts. I think I’ve probably spent too much time expressing an anxiety about Lee’s influence, but that’s coming to an end now and a new period is beginning. I loved Lee, but he is gone. And the decisions I will make for this company have already been bold, I hope, and strong, and driven by a creative integrity that is finding its feet in new ways every day. Every great design house knows that legacy cannot be allowed to be a curse and must be a wonderful opportunity for invention. That’s where I am. That’s who we are.”

It’s worth remembering the motto at Withington Girls’ School, where Burton was a happy pupil in the 1980s: “ad lucem” — toward the light. That is the general direction of her life and her talent. Her husband, David Burton, is also her best friend, and they have twin girls. If you’re available for optimism, as she is, then the movement toward the light will come naturally, with all the opposing shadows existing like ghosts on a glass negative. In her fall show for Alexander McQueen, Burton set all this to life, like a magician of selfhood. A strange, misty moorland — not unconnected to the landscape of her childhood — was the setting for the combination of beautiful tailoring and wild imaginings that characterize the house. There was a sense of romanticism-in-crisis, of the Bronte sisters, of Heathcliff haunted by the cold hand of death scratching at his window, of owls, dreams and the poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, whom Burton cites. The dresses came with capes, fur hoods, bell sleeves and delicate, small embroidery, frilled and frayed hemlines. Clothes like these don’t make themselves, and legacy doesn’t make them either. Some designers are driven not by what is flamboyant in them but by what is recessive. Burton brings to the McQueen brand an English tendency toward dark pleasure as opposed to dark pain. She is a prettier designer than many, but always alert to the mysteriously perverse.

Not everyone has obvious demons. With Lee it was skulls, shipwrecks, hospital inmates and birds of prey. But Burton’s instinct might be more subtle. Her instinct might be to see the fly in the ointment, the crack in the teacup, the little details that make the ordinary strange.

“When I went to Saint Martins” — the art school she attended — “a lot of the people there were these flamboyant characters. I thought, ‘God, I’m not like them.’ I thought, ‘What’s going on? I’m really normal.’ But my own demon is the fear of failure. My obsessional addiction is work and there’s a possible twistedness in always putting myself last, you know?”

“Were you never really interested in being a star designer?”

“Honestly, no. There have been times when, if I could have disappeared from this industry I would have. I had to battle with it. I don’t look like a fashion person, I’m not cool, and I always just loved people who are good at what they do. I’m not interested in going to parties. I hate having my picture taken. When the Met Ball is happening I want to go through the back door. When the giant McQueen show was on there” — which became the biggest draw in the history of the museum — “I didn’t want to go up the red carpet because . . . it’s embarrassing. I’m shy. When celebrities tap me on the shoulder I think they’re asking me to move out of the way. And you know: It doesn’t bother me. I smile about it with my husband, we’re secure. And to me the only story that is worth telling is the story of the work.”

Someone who works with Burton told me about the pressure she came under to accept the job at McQueen. She was approached for the creative directorship of another major fashion house at the same time and this person told her she’d regret not accepting the offer. “You’ll always be haunted at McQueen,” she said. After Lee’s suicide, the co-worker remembers Burton burning a candle in Lee’s room and leaving off the lights: “There was just this candle. Sarah had this giant decision to make. And we were all relieved when she took the job. We always knew she had a whole vision of her own that helped Lee’s vision but was peculiar to her.”

Burton told me she was relieved to be able to talk again about the basics of design and inspiration. She felt she’d been tossed around in a sea of media obsessions — the hunger for news about her relationship with the royals still persists, and a few days before we first met, the media camped on her doorstep again, convinced she had designed Kim Kardashian’s wedding dress, which she hadn’t. With me she became more relaxed, saying it was nice to be back on dry land, talking about ideas, trying to define her way of doing things in a job she loves.

“What have clothes to do with emotion?” I asked.

“Oh, everything,” she said. “They can describe a moment in your life or a feeling that is completely instilled in you. Feeling the texture of the material and seeing how it moves on the body, well, that is emotion — it’s emotion-in-motion. It might interest you to know that the clothes that sell best in our shops is the most extreme stuff — people want to express something about themselves and they find an enabler in us, and that’s emotional.”

One of the reasons Burton has shied away from the media is because certain quarters of it have pursued her. Her biggest project to date, making the royal wedding dress in 2011, meant the press stalked her for months, and the stress of trying to keep the secret and trying to deal with bogus stories came fast on the heels of Lee’s death. The dress was universally admired and it made Alexander McQueen a household name, but there are critics who say she has been too silent. “I had no idea it would be as big as it was. Only the night before, seeing all the photographers outside the abbey, did I think, ‘Oh, my God. This is massive.’ ”

When I first brought the dress up with Burton, she wanted to wave the subject away. But during our second meeting, she appeared resolved to put the matter to rest. “I know we live in a culture obsessed with fame,” she said, “but I happen to believe privacy is a virtue, and the relationship I have with my clients is private. Some people like to think I’ve been too shy or that I’m afraid to speak up about the happy experience I had creating the Duchess of Cambridge’s wedding dress, but I can tell you that is nonsense. I have never been a shrinking violet or a person who is ruled by fear. I loved making the dress, I loved adapting my ideas to suit the person and the occasion, and we put our hearts into it. I respect the intimate nature of that lovely project and I respect the friendships that were forged during it. This is the era of blab, but we’re strong-minded here at McQueen, we always have been, and we’re proud of what we do. There are people in the media who will always want to invent sinister reasons for people’s discretion, but an instinctive, intelligent, imaginative young woman’s wish for a beautiful wedding dress — or any kind of dress — is the most natural thing in the world. And I was honored to pick up the challenge and always will be.”

So there you have it. Does that sound like a frightened artist to you? Like someone playing second fiddle to anyone? She made the most famous dress in the world and survived to tell us that the tale is hers. It provides a perfect antidote to the prurience of our times and shows Burton to be willing not only to take her values into her workplace, into her home life, but now, after a season of rain, into the sunny uplands of her public image.

When I popped backstage to see her after her recent men’s wear show in London, there was a queue of international glamour types lining up to praise what she’d done. It was quite a show — long, lean coats with flashes of red lining, made in Prince of Wales check or houndstooth, with abstract Kabuki patterns lifting them out of England — but she waved off the praise, then smiled broadly when the elderly mother of the show’s hairstylist came up. “Oh, you’re the belle of the ball, so I won’t keep you,” the lady said. “But how’s the kids? Great. Well, let’s be seeing you before long, darling — you’re looking lovely.”

“Would you sooner come back as a butterfly or a bee?” I asked her.

“Oh, a bee,” she said, her Northern accent suddenly obvious. “I think I’m more of a worker than I am a painted lady.” Everybody who knows Burton admires her, and many of them have waited patiently for her to speak out without being hesitant, to embrace the success she’s having, and to let the light of Alexander McQueen shine equally on the past and the present. She now has her own legacy to think about. “We’re in the enchantment business,” she said. “Fashion will never stagnate so long as there are teams of people willing to tackle the soul of the culture. That’s what we do here at McQueen, that’s what we’ve always done.”

helmutnotdead

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 29, 2018

- Messages

- 2,049

- Reaction score

- 5,602

I was certainly not expecting this.

Gaultier_Bandit

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 6, 2008

- Messages

- 2,370

- Reaction score

- 143

I really hope Tisci is being considered

Thefrenchy

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Nov 13, 2006

- Messages

- 12,356

- Reaction score

- 3,273

Wasn't expecting it either. Never liked her work there, she diluted the house in my opinion. But kudos for longevity. I wonder who will try to fill Lee's shoes now, because she never managed to. In all fairness, I doubt anyone ever will. It's going to be interesting to see what kind of profile they are going to want to select.

Similar Threads

- Replies

- 733

- Views

- 104K

- Replies

- 49

- Views

- 8K

- Replies

- 266

- Views

- 43K

- Replies

- 2K

- Views

- 165K

- Replies

- 2

- Views

- 3K

Users who are viewing this thread

Total: 2 (members: 0, guests: 2)