Ann Demeulemeester's Heavy Career in a Heavy New Book

by Eugene Rabkin

A long-awaited and very weighty monograph on Ann Demeulemeester (Rizzoli, $100) is being released in November. When we met in Antwerp in April, the influential Belgian designer had just sent off the final draft to the publisher, and she spoke of it as if it were the perfect closure to her body of work in fashion, an exclamation point on the last sentence of her career, a tome in itself.

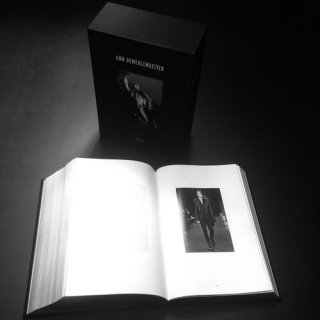

The cloth-bound book is, obviously, black and comes in a matching slipcase, with Demeulemeester’s signature two thin and long black tassels serving as ribbon markers. Her husband, Patrick Robyn, is responsible for much of the early photography, while her son, Victor, helped her design and compile the volume. It’s not a regular, large-format coffee table affair, but its thickness is a physical reminder of how rich Demeulemeester’s career in fashion has been. As a matter of fact, if not for the thin paper stock, the 2000-page tome might prove unwieldy.

The only text in the book is an introduction by Patti Smith, who has been a close friend of Demeulemeester’s for years. Poetic, as usual, it begins with Demeulemeester discovering Smith’s Horses album. She was passing by a record shop when she was struck by the image of a young Smith in a plain white shirt. Years later, Demeulemeester summoned the courage to send Smith a package with three of her own white shirts. WIth that, their friendship was born.

In a few strokes, Smith's introduction paints the raison d'être of Demeulemeester’s work. It was not a preoccupation with fashion that drew Demeulemeester to it, but a deep-rooted interest in clothing as an expression of character. She ends on a fitting note: “The girl of Flanders has walked her own path, in her own black boots.”

The rest of the book consists of images, over 1000 of them. They occupy the center of each page, surrounded by plenty of white space. The first part is a treasure trove of early photography, virtually impossible to come by in the pre-Internet era. From these you can glean how early some signature elements of Demeulemeester’s aesthetic appeared: the predominantly black and white palette, the use of feathers, Edwardian cuts, and those famous tassels. The influence of menswear, too, becomes apparent, even though Demeulemeester did not present a men’s capsule until 1996.

The images continue on to the runway shows, starting in 1992 in Paris. There are no breaks of any kind to separate one collection from the next (you can refer to the index in the back) — a reminder that Demeulemeester sees her work as one continuous, undivided series of chapters.

The rest is all pictures, b/w and color. The pictures are pretty small and all the same size as in the above posted preview. The highlight are all the photos of her early work, of course.

The rest is all pictures, b/w and color. The pictures are pretty small and all the same size as in the above posted preview. The highlight are all the photos of her early work, of course.